Ahmed Mater

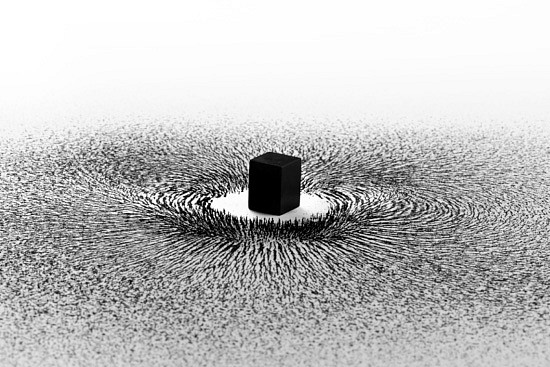

Ahmed Mater

Magnetism III, 2012

Diasec Mounted Fine Art Latex Jet Print

226 x 281 x 6 cm (89 x 110 5/8 x 2 3/8 in.)

From Magnetism series, Edition of 8

AHM0101

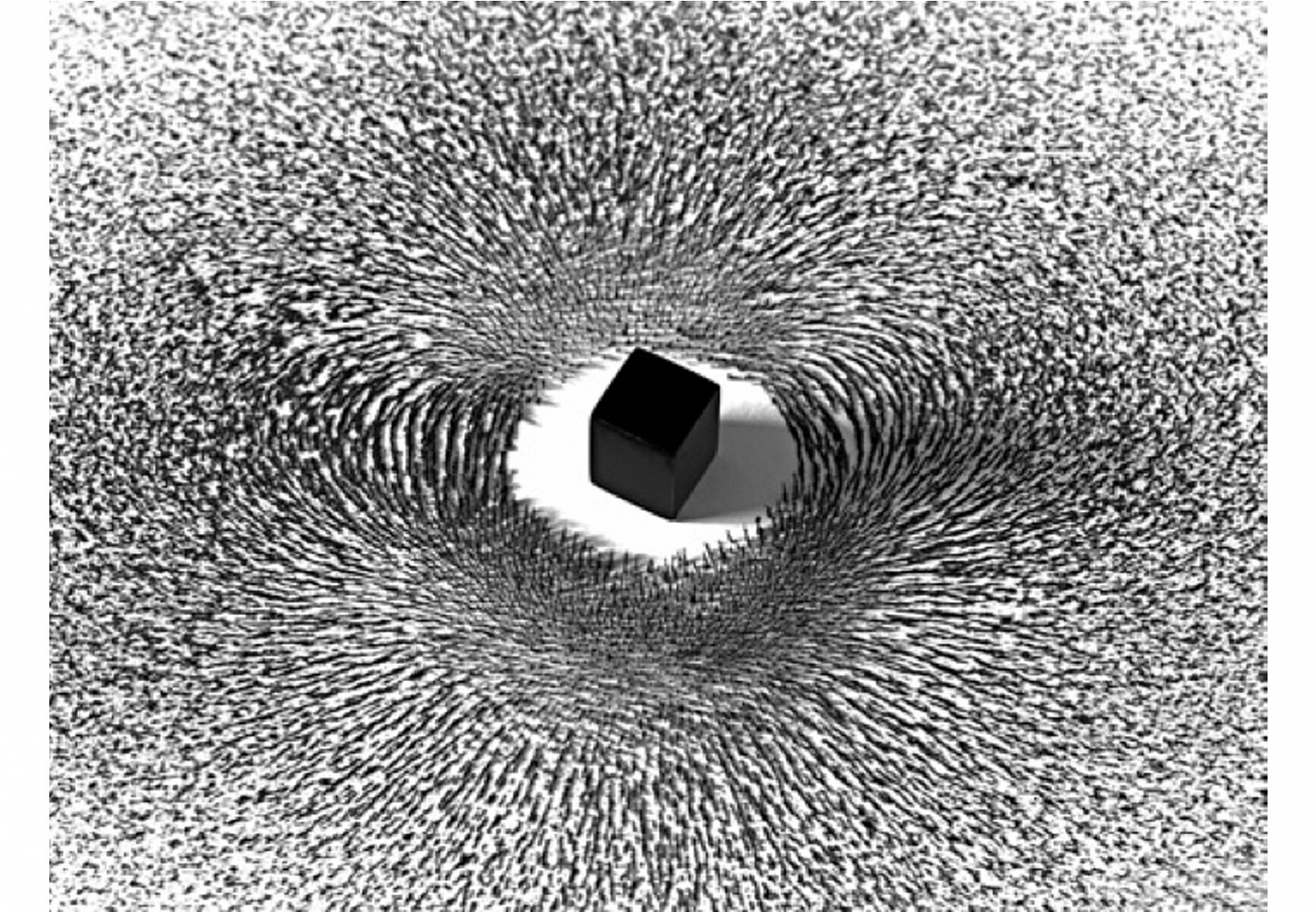

Ahmed Mater

Magnetism IV, 2012

Diasec Mounted Fine Art Latex Jet Print

250 x 300 cm (98 3/8 x 118 1/8 in.)

AHM0066

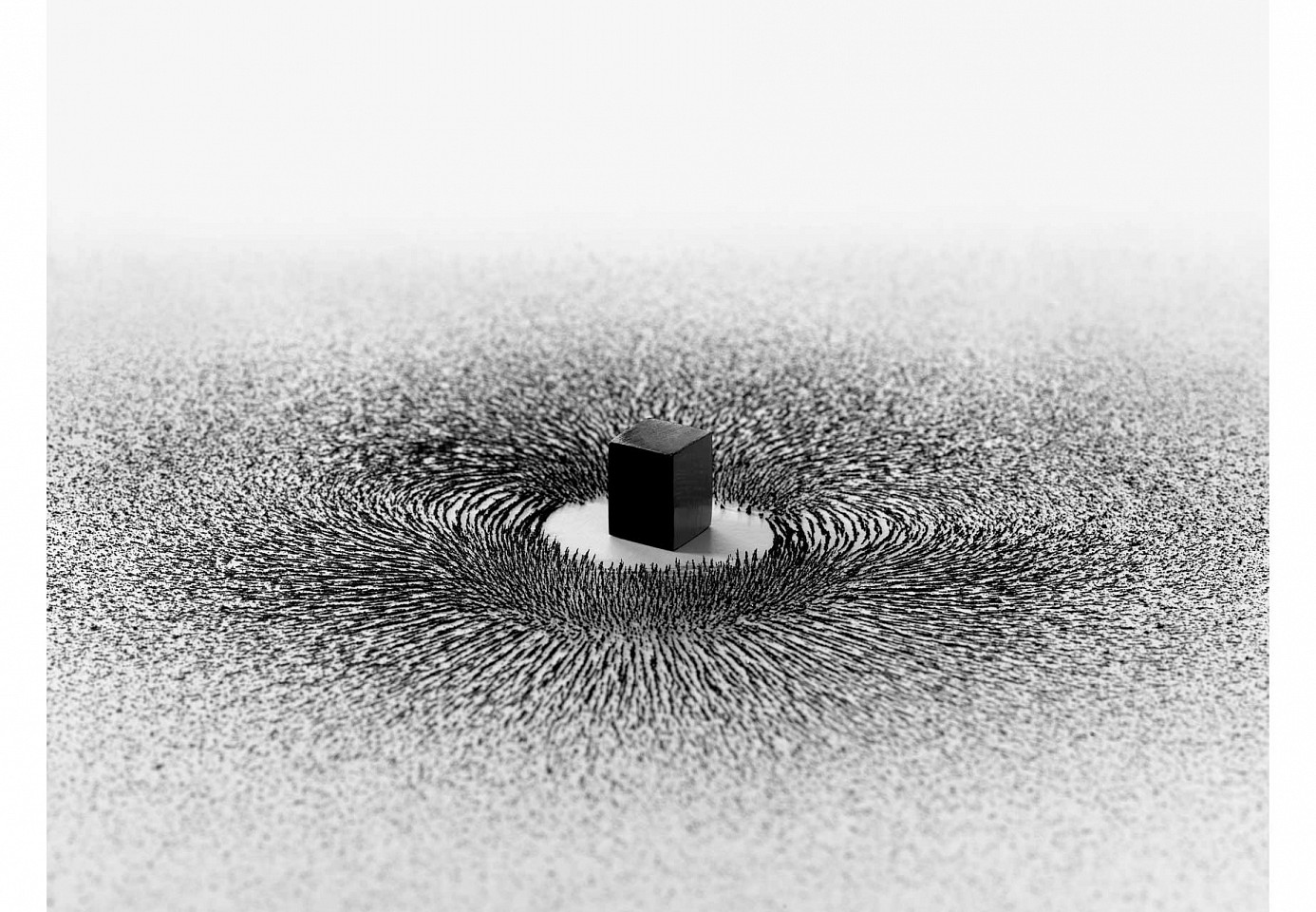

Ahmed Mater

Magnetism V, 2012

Diasec Mounted Fine Art Latex Jet Print

226 x 282 x 6 cm (89 x 111 x 2 3/8 in.)

AHM0077

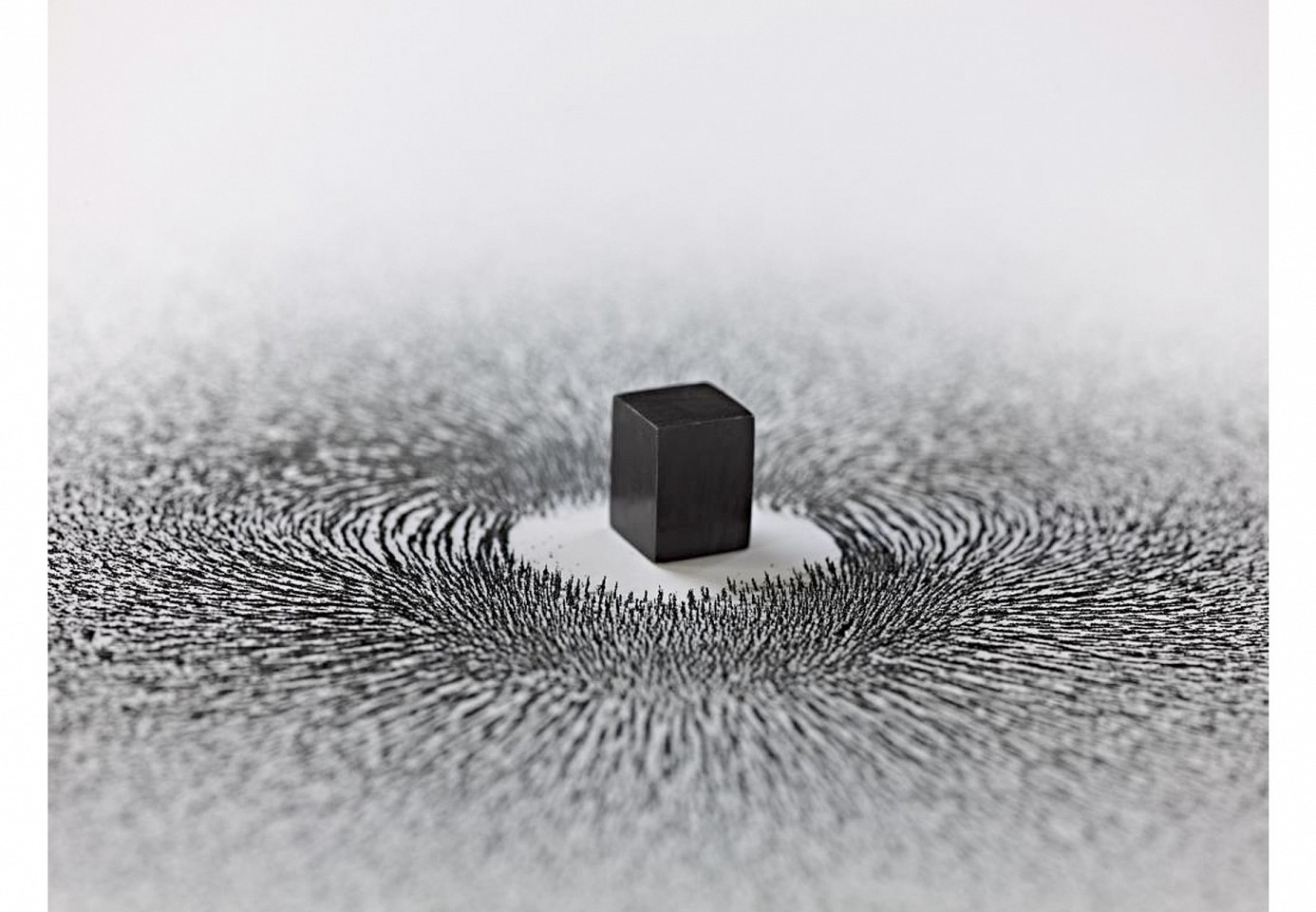

Ahmed Mater

Magnetism Installation, 2009

Magnet and iron shavings

200 x 90 x 90 cm (78 11/16 x 35 3/8 x 35 3/8 in.)

From Magnetism series, Edition of 5

AHM0173

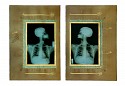

Ahmed Mater

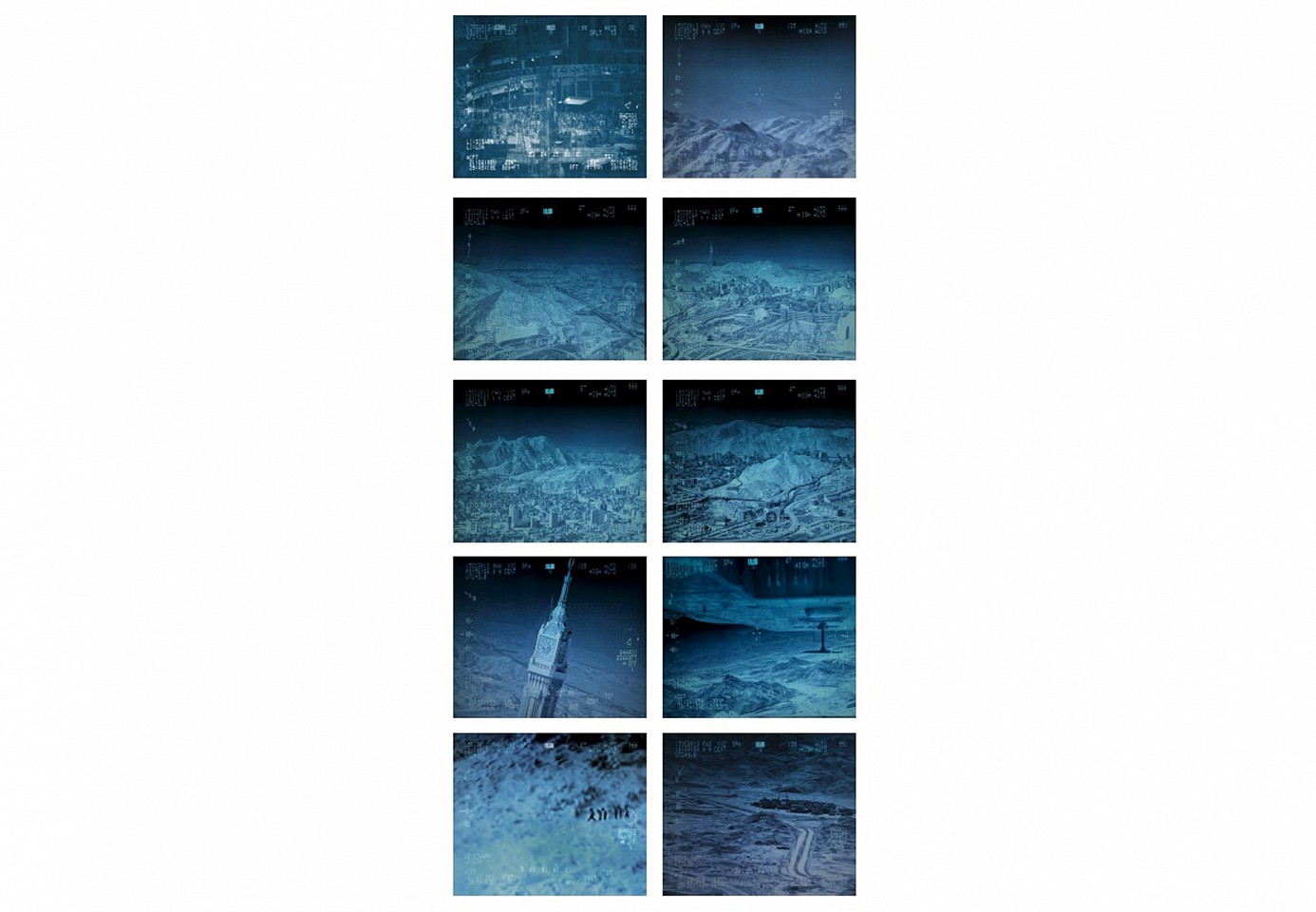

Disarm, 2013

10 LED light boxes

31 x 37 cm (12 3/16 x 14 9/16 in.)

Edition of 5 + 1 AP, From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0189

Ahmed Mater

Disarm 01, 2013

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/16 x 78 11/16 in.)

Edition of 5 + 1 AP, From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0179

Ahmed Mater

Disarm 02, 2013

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/16 x 78 11/16 in.)

Edition of 5 + 1 AP, From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0184

Ahmed Mater

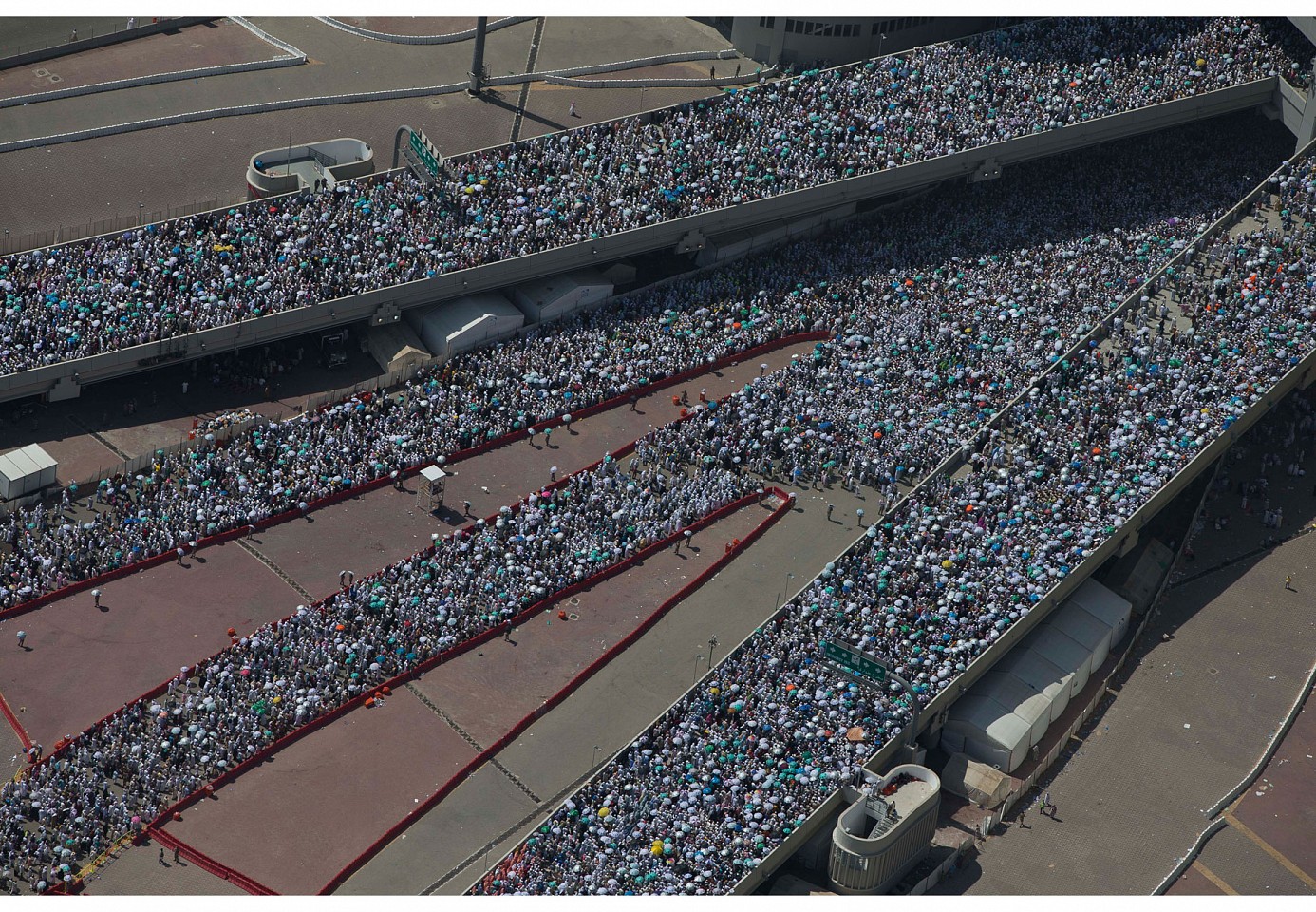

Human Highway (Mina), 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

AHM0067

Ahmed Mater

Artificial Light Construction, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

AHM0072

Ahmed Mater

The Courtyard of Paradise, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0028

Ahmed Mater

Social Fabric, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0038

Ahmed Mater

Artificial Light, 2011

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

245 x 342.5 cm (96 1/2 x 134 7/8 in.)

Edition of 3; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0020

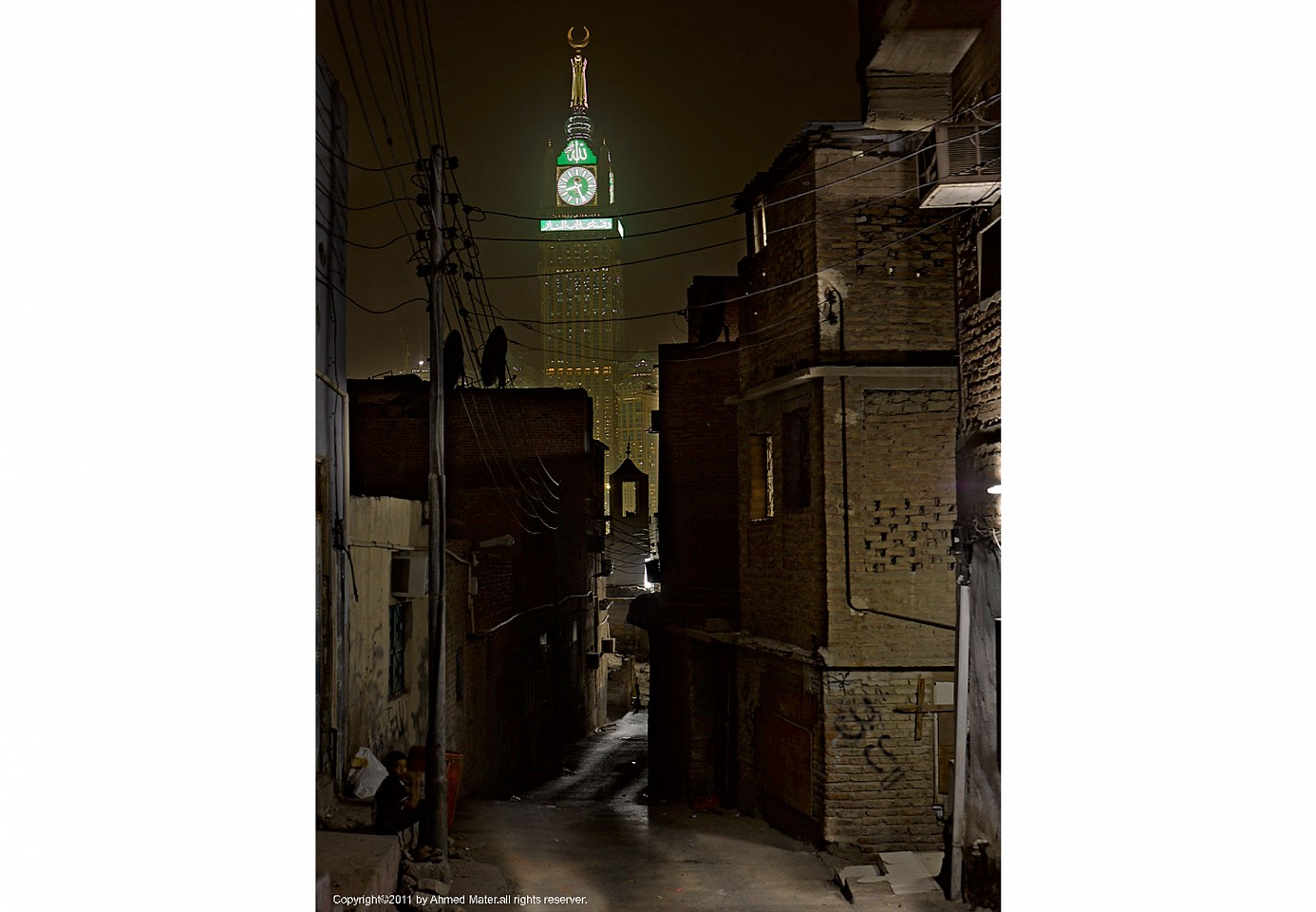

Ahmed Mater

Abraaj Al Bait Tower, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0023

Ahmed Mater

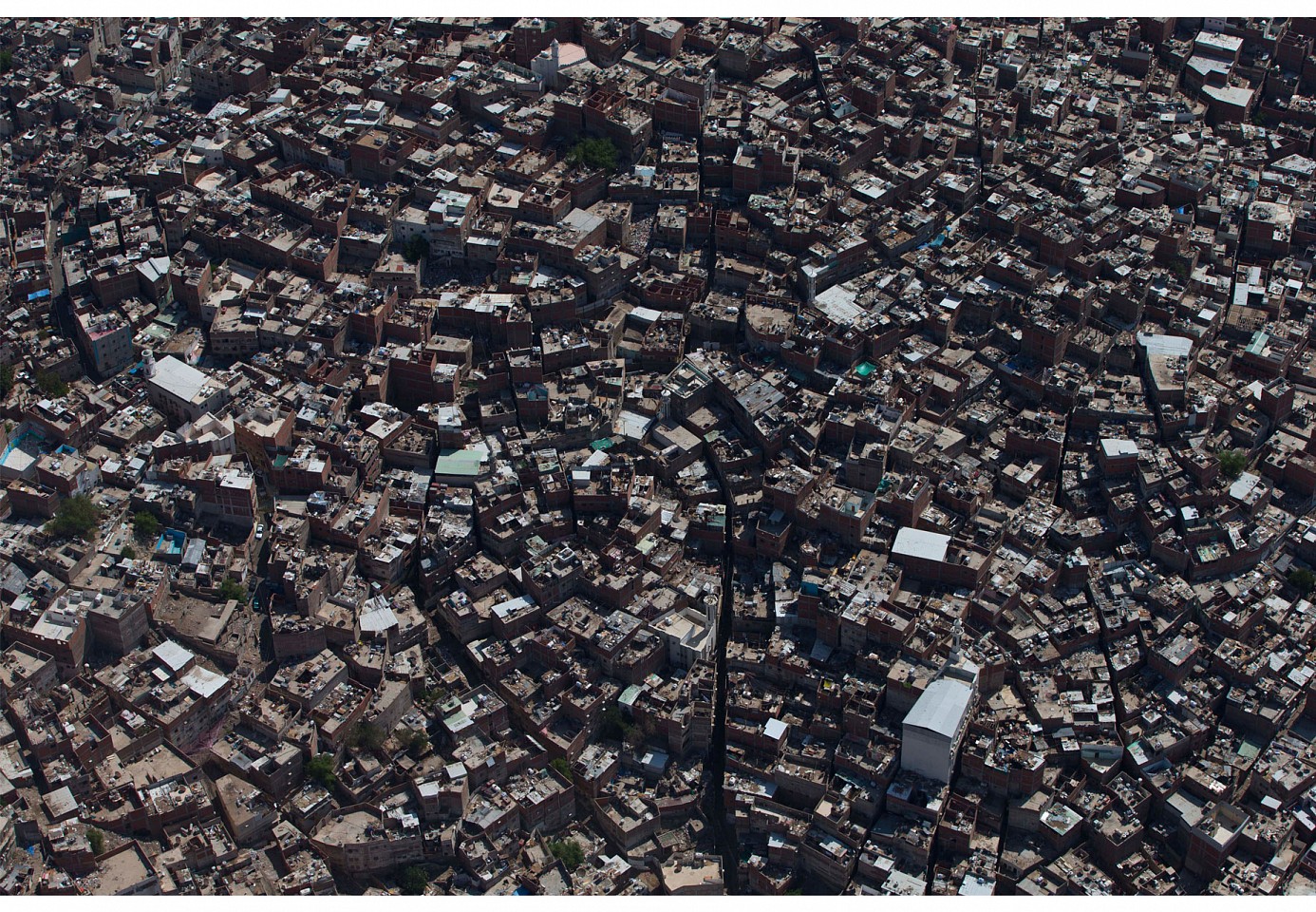

Al Mansur District, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0033

Ahmed Mater

Golden Hour, 2011

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

245 x 326.5 cm (96 1/2 x 128 1/2 in.)

Edition of 3; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0017

Ahmed Mater

Human Highway, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0043

Ahmed Mater

Abraaj Al Bait, AC Tower, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

180 x 140 cm (70 7/8 x 55 1/8 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0053

Ahmed Mater

Pelt Him!, 2012

1'03 mins

Edition of 5

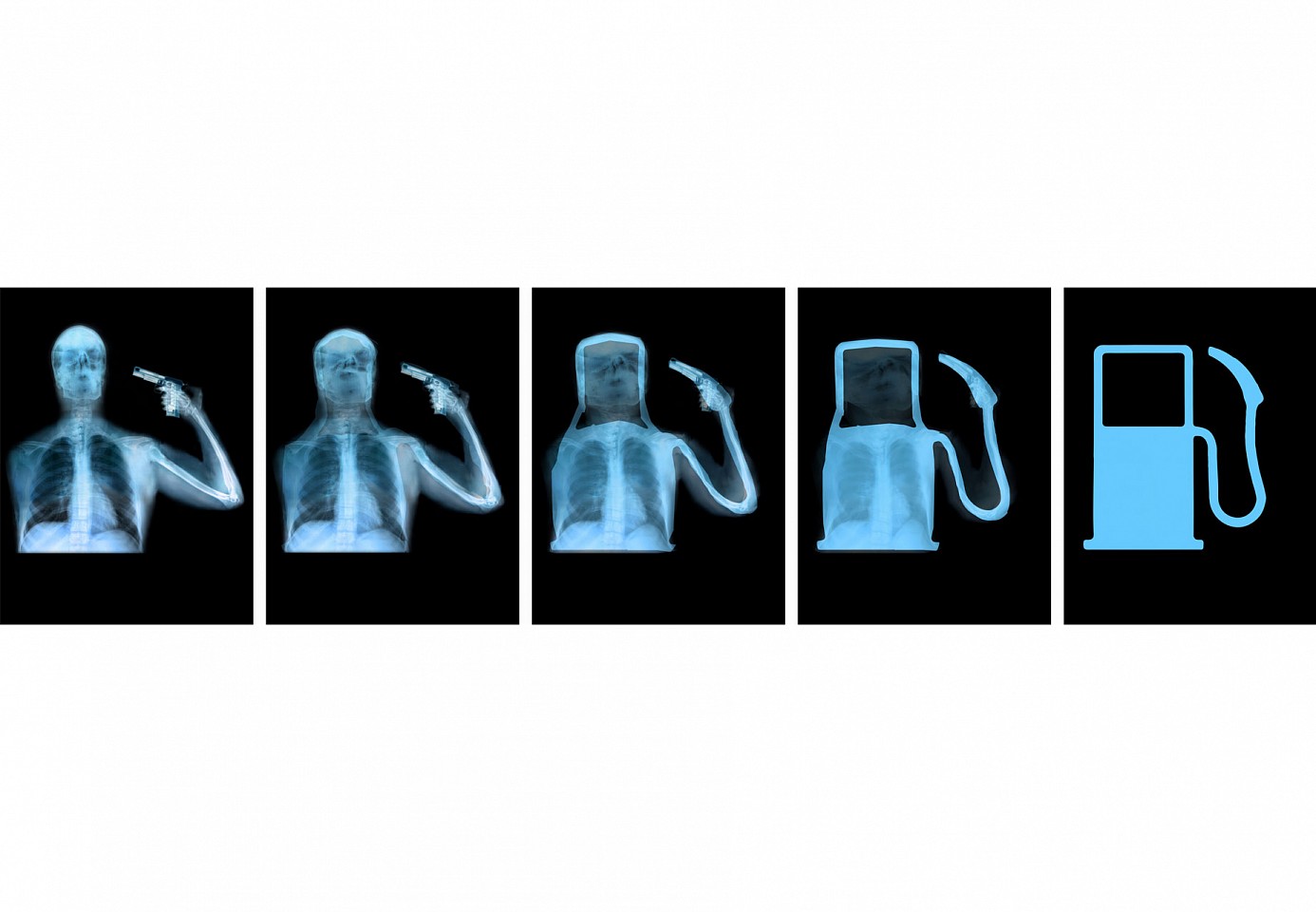

Ahmed Mater

Evolution Of Man, 2010

5 silk-screen prints signed and numbered by the artist Printed with 11 colours on 400GSM Somerset Tub paper

80 x 60 cm (31 1/2 x 23 5/8 in.)

Edition of 100

AHM0000

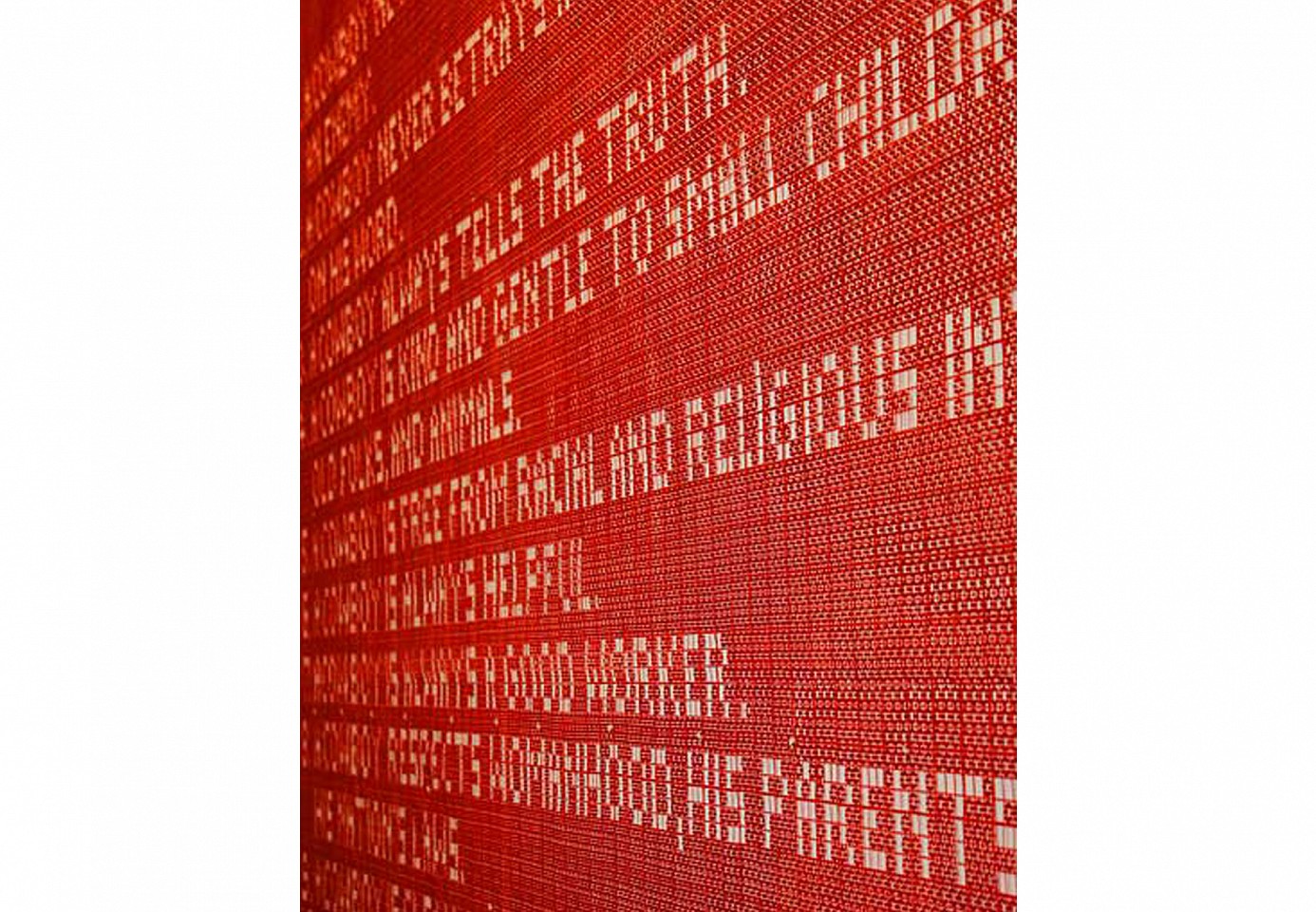

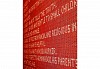

Ahmed Mater

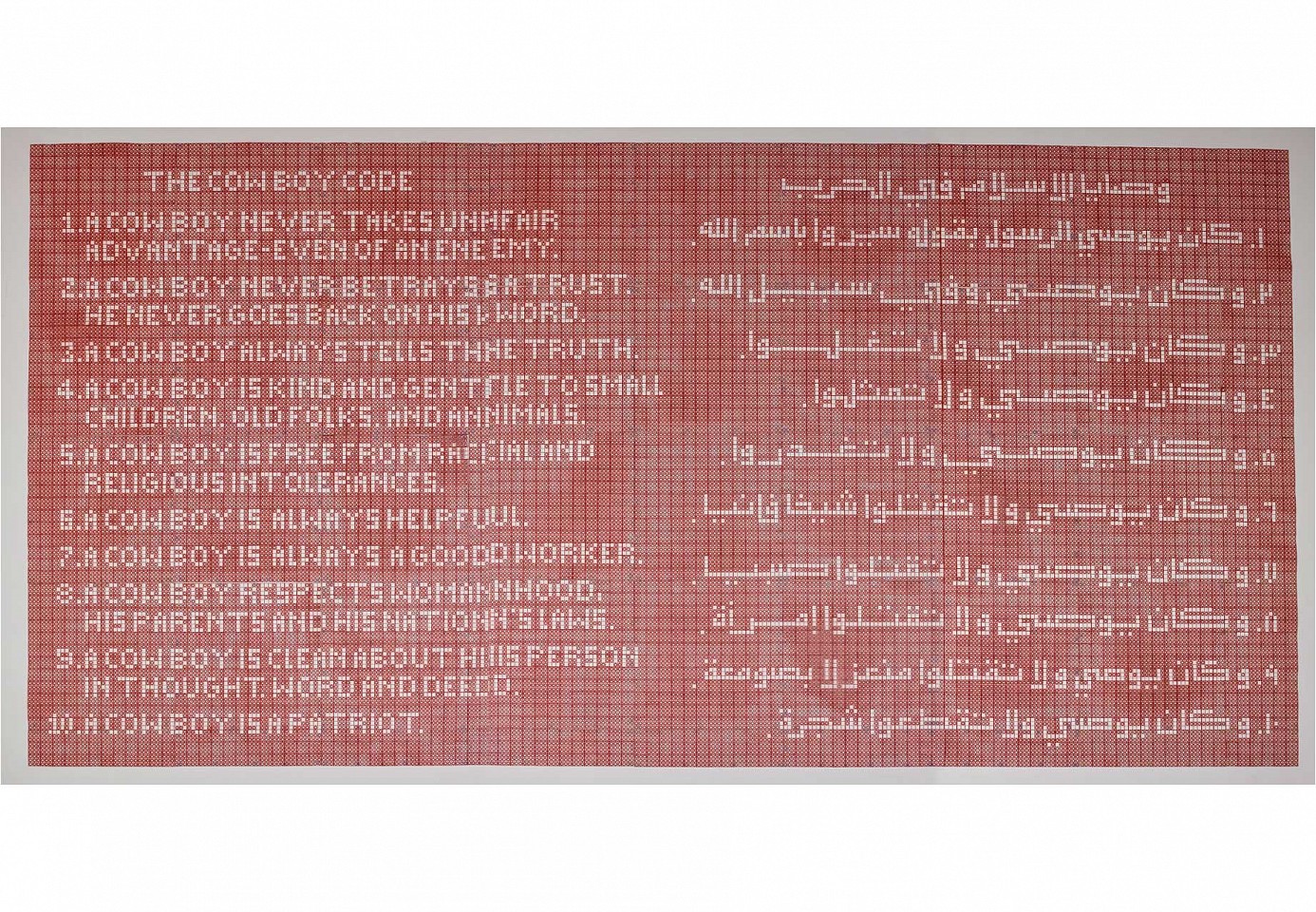

Cowboy Code, 2011

Mixed Media

450 x 450 cm (177 1/8 x 177 1/8 in.)

Edition of 3

AHM0010

Ahmed Mater

Antenna, 2010

Neon Tubes

150 x 150 x 50 cm (59 x 59 x 19 5/8 in.)

Edition of 2

AHM0008

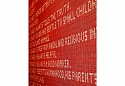

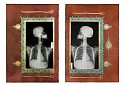

Ahmed Mater

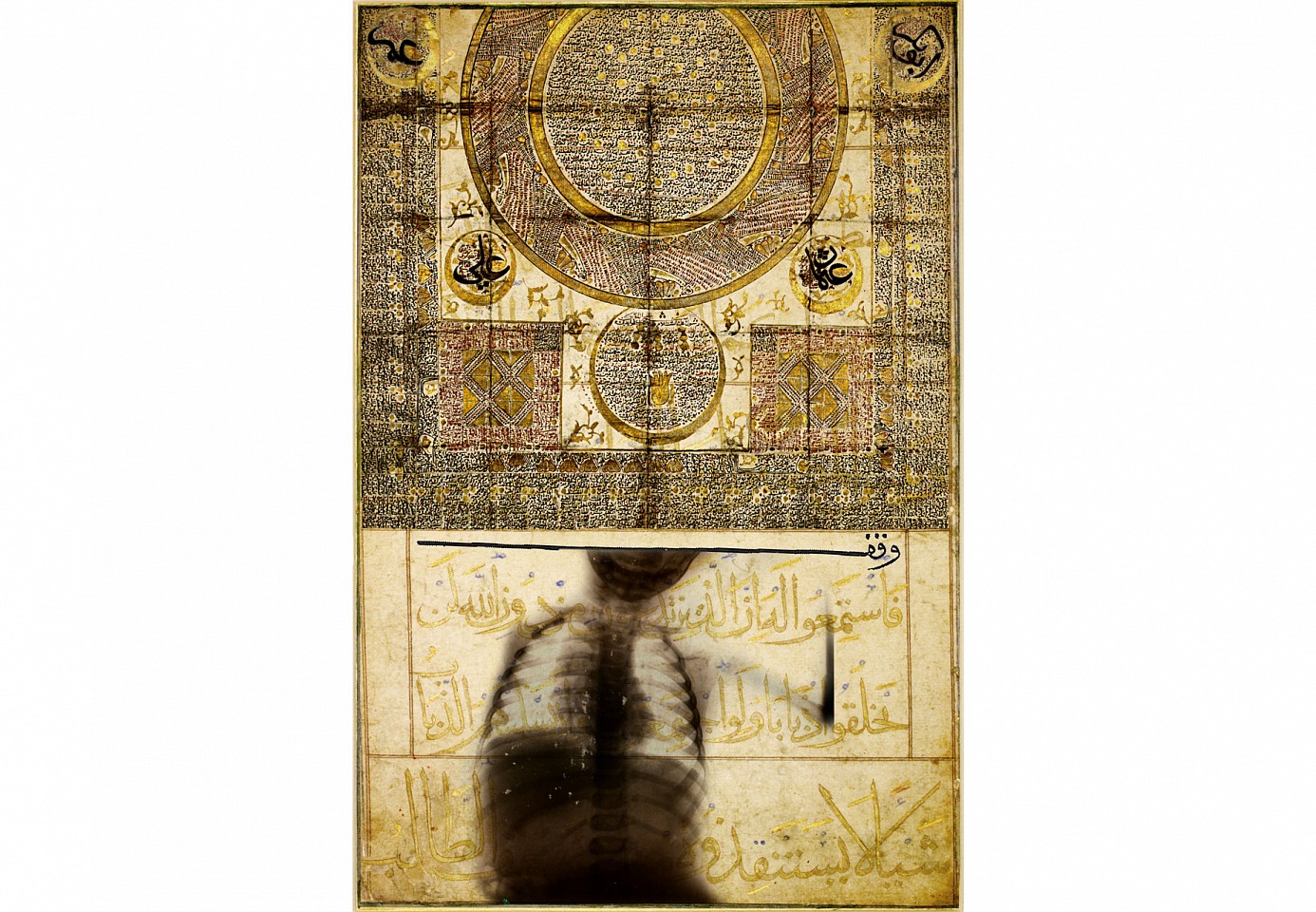

Illumination Makkiah, 2013

Gold leaf, tea, pomegranate, Dupont Chinese ink and offset X-ray film print on archival Arches paper

155 x 110 cm (61 x 43 1/4 in.)

From Illumination series

AHM0201

Ahmed Mater

Illumination Talisman III, 2013

Gold leaf, tea, pomegranate, Dupont Chinese ink and offset X-ray film print on archival Arches paper

155 x 110 cm (61 x 43 1/4 in.)

From Illumination series

AHM0085

Ahmed Mater

Illuminations Madniate Alhijrah, 2013

Gold leaf, tea, pomegranate, Dupont Chinese ink and offset X-ray film print on archival Arches paper

155 x 110 cm (61 x 43 1/4 in.)

From Illumination series

AHM0202

Ahmed Mater

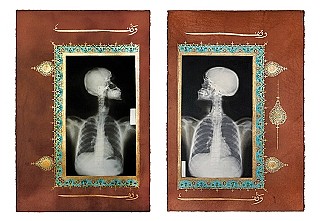

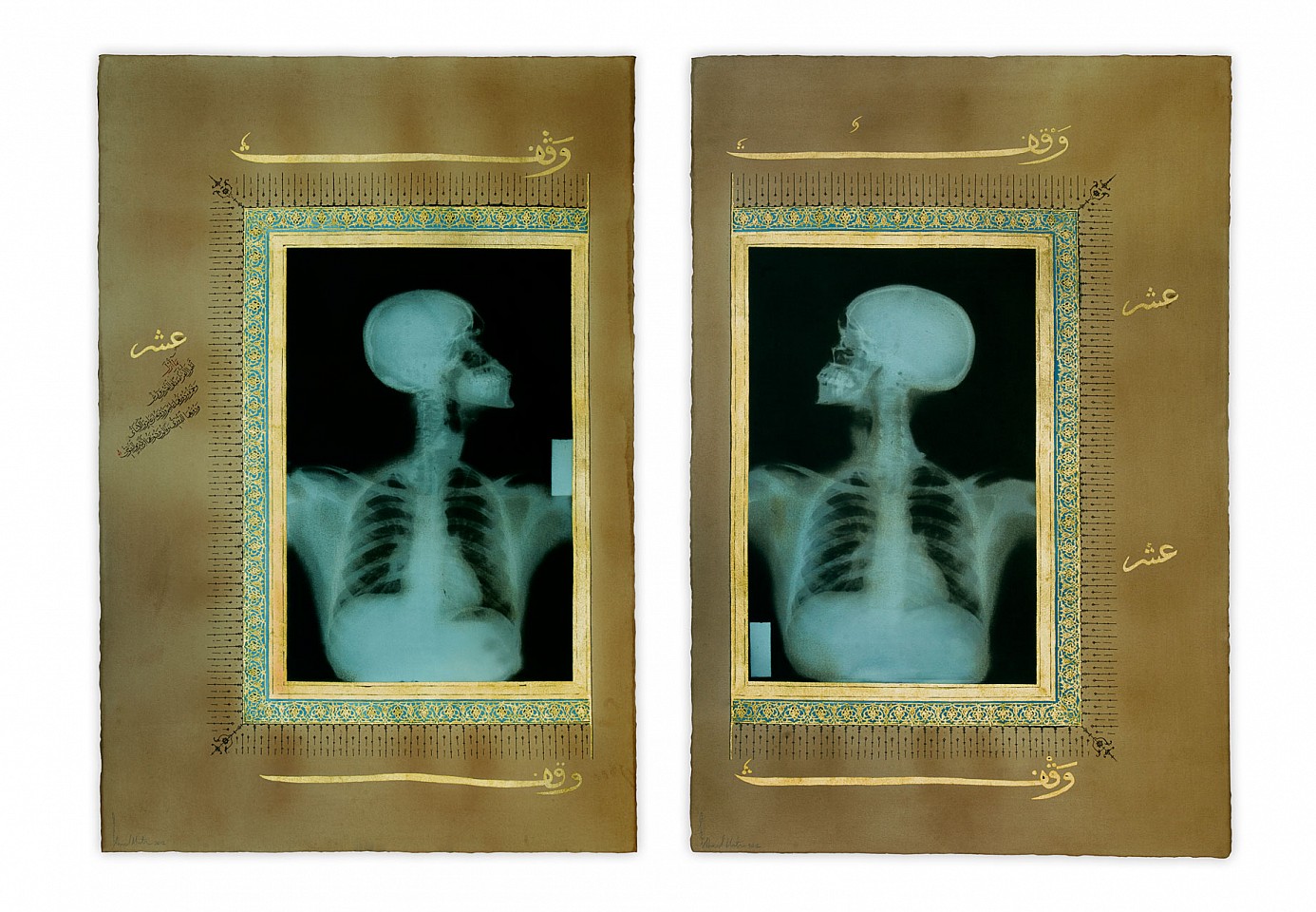

Illuminations (diptyk), 2012

Gold Leaf, Tea, Pomegranate, Dupont Chinese ink & offset X-Ray film print on paper

152 x 102 cm (59 7/8 x 40 1/8 in.)

AHM0064

Ahmed Mater

Cowboy Code II, 2012

Plastic Gun Powder Caps

400 x 800 cm (157 7/16 x 314 15/16 in.)

AHM0231

Ahmed Mater

Northern Gate, 2012

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

245 x 326.5 cm (96 1/2 x 128 1/2 in.)

From Desert of Pharan series, Edition of 3

AHM0109

Ahmed Mater

View Masters and Slides Installation, 2014

3 various View Masters

24 C- prints, 40 x 40 cm each

Edition of 10 Image courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation

AHM0204

Ahmed Mater

Nature Morte, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 143 cm (55 1/8 x 56 1/4 in.)

From Desert of Pharan series, Edition of 5

AHM0115

Ahmed Mater

Namira Mosque, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/16 x 78 11/16 in.)

From Desert of Pharan series, Edition of 5

AHM0125

Ahmed Mater

Untitled, 2012

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

145 x 200 cm (57 1/16 x 78 11/16 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0220

Ahmed Mater

Let it Be Passed, 2012

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

145 x 200 cm (57 1/16 x 78 11/16 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0215

Ahmed Mater

Pelt Him!, 2014

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

182 x 142 cm (71 5/8 x 55 7/8 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0225

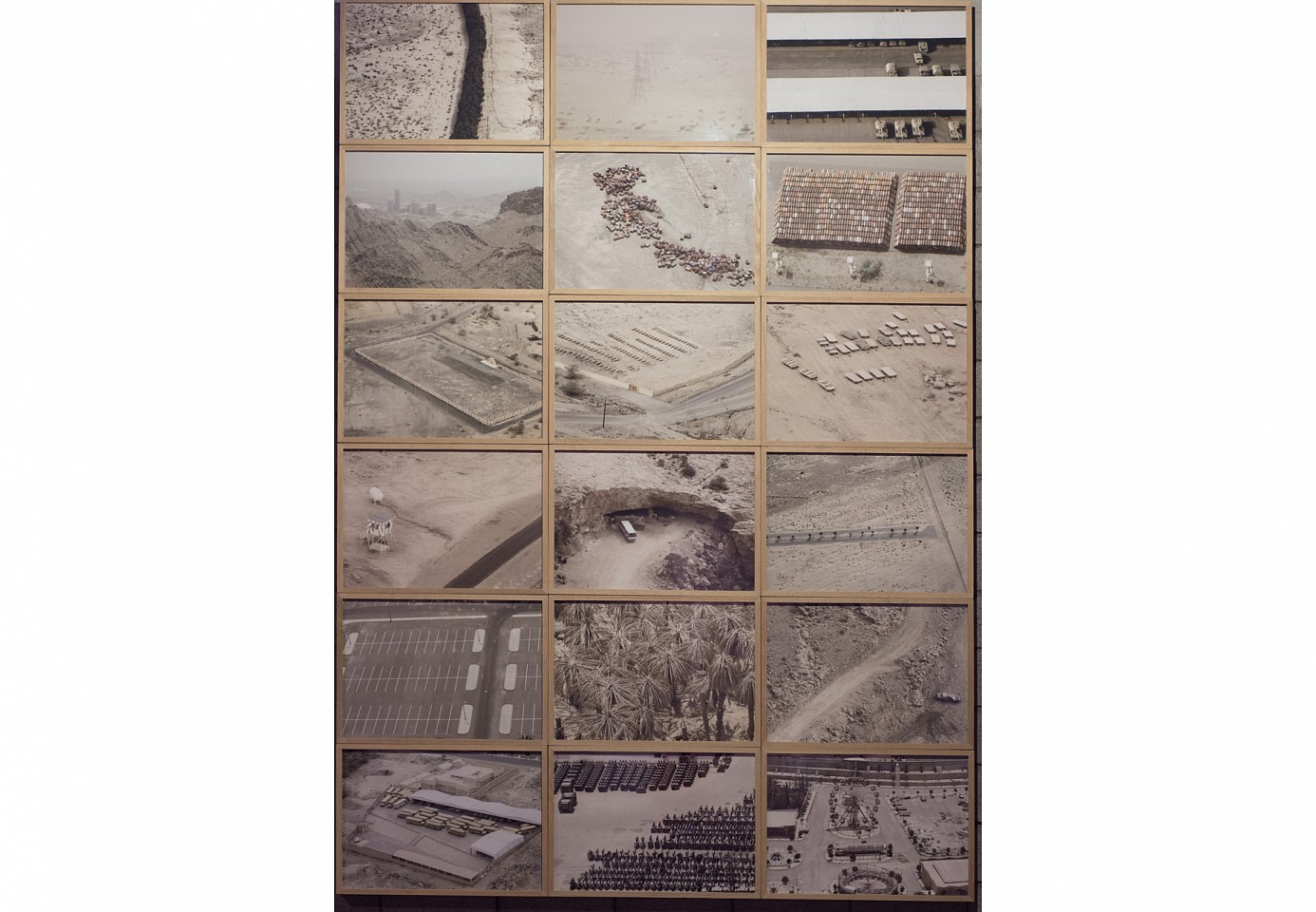

Ahmed Mater

Empty Lands, 2012

Photography (x18)

Edition of 3

AHM0112

Ahmed Mater

The Return, 2015

Diptych, Print on fine art paper

100 x 150 cm (39 5/16 x 59 in.)

Edition of 5, From the Desert of Pharan series

AHM0320

Ahmed Mater

Leaves Fall in All Seasons, 2012

Video installation

Running Time 19:57 mins

From Desert of Pharan series, Edition of 5

AHM0135

Ahmed Mater

Yellow Cow Poster, 2010

Mixed Media

142 x 114 cm (55 7/8 x 44 7/8 in.)

Edition of 35

AHM0001

Ahmed Mater

Grey Eagle, 2022

High density polyurethane and HSL 3d print covered by acrylic one and sand

AHM0421

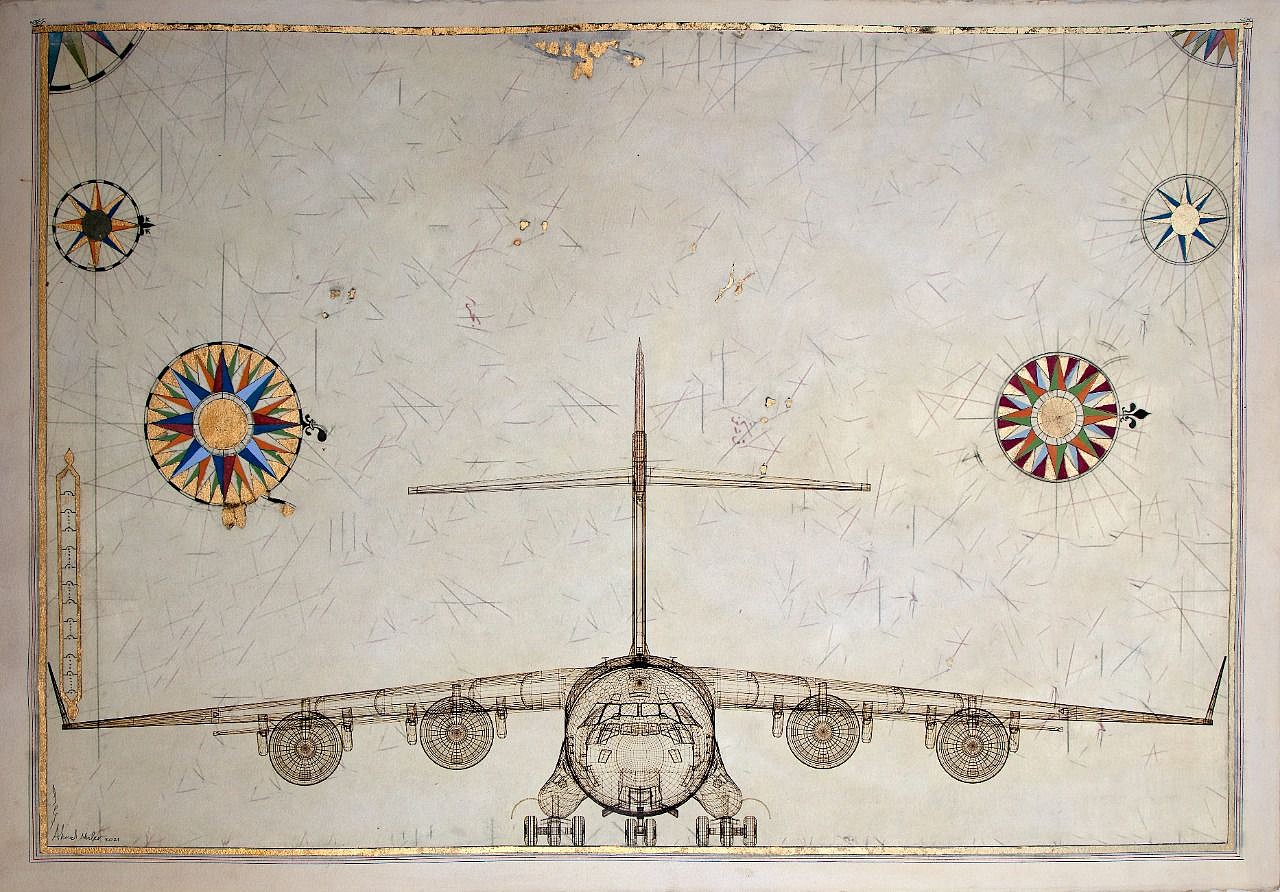

Ahmed Mater

C17, 2021

Mixed Media

AHM0416

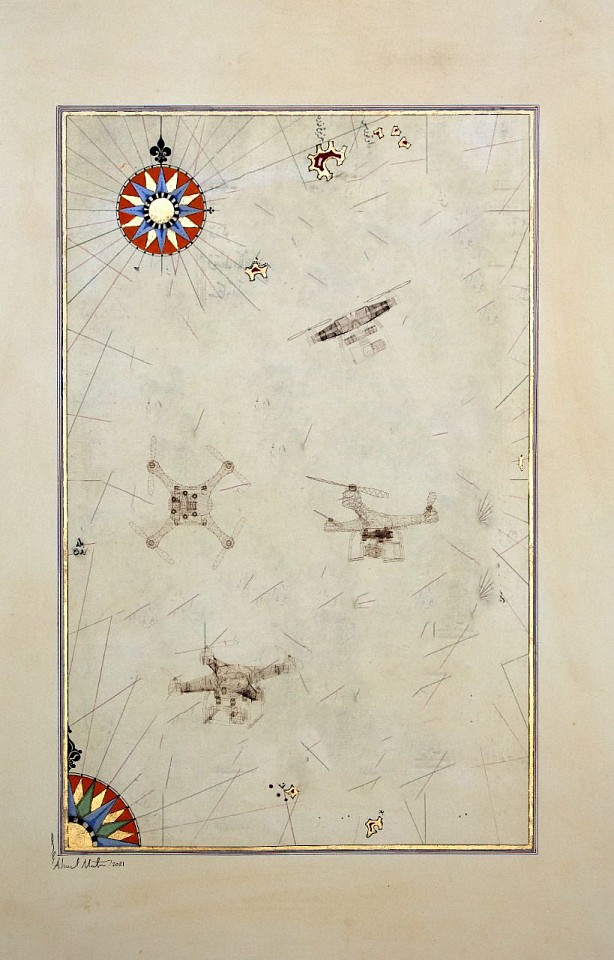

Ahmed Mater

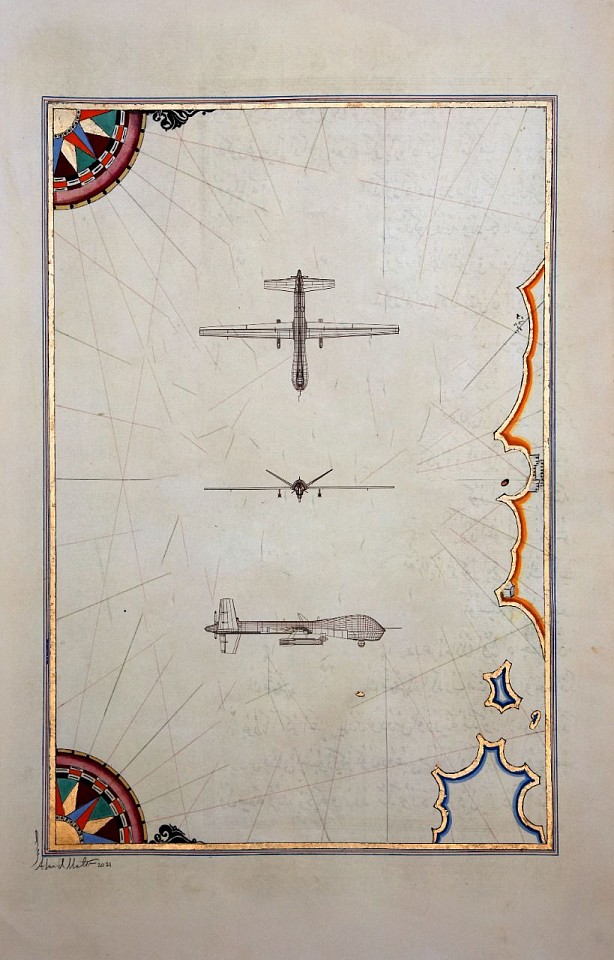

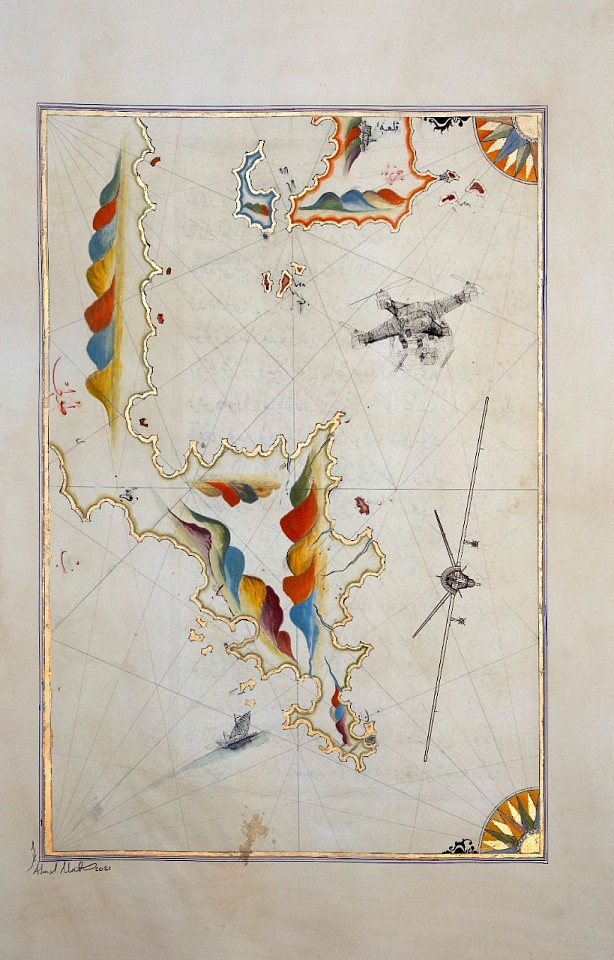

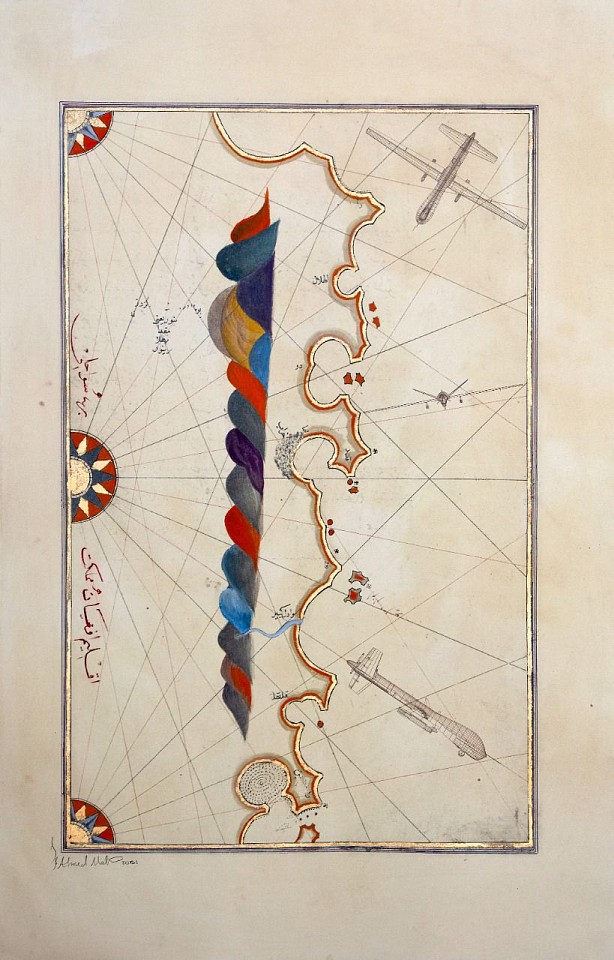

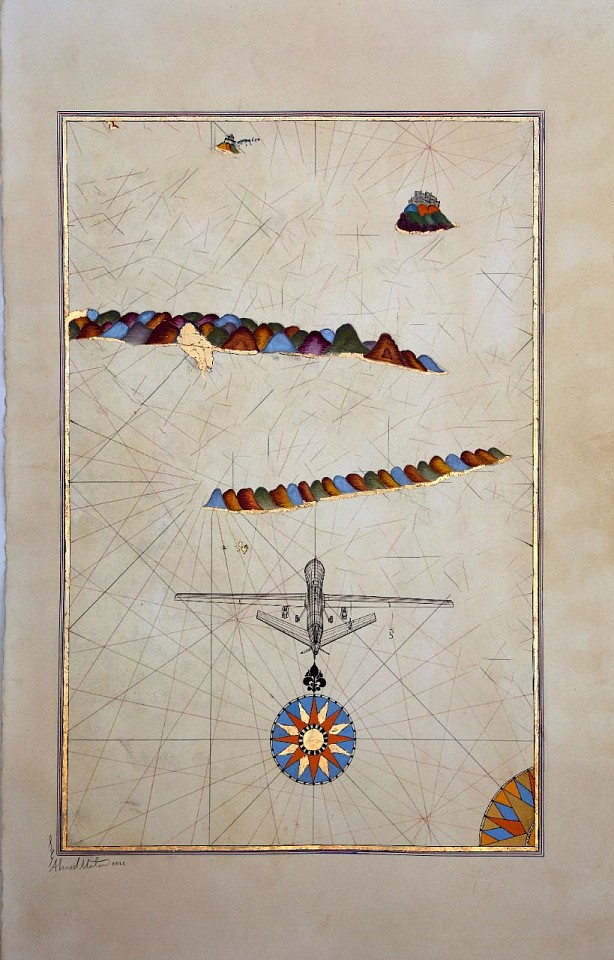

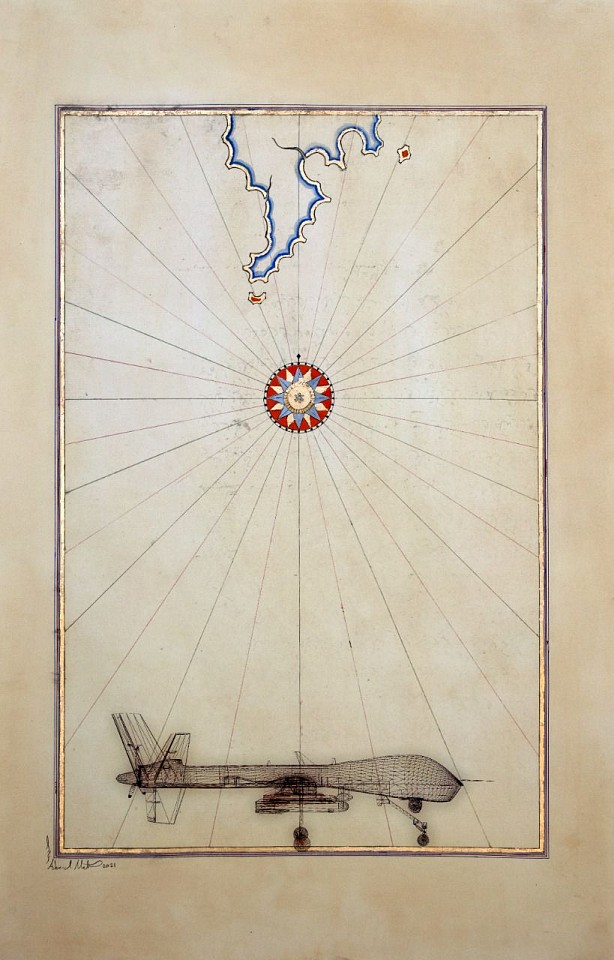

IIllumination Grey Eagle # 1, 2021

Mixed Media

AHM0408

Ahmed Mater

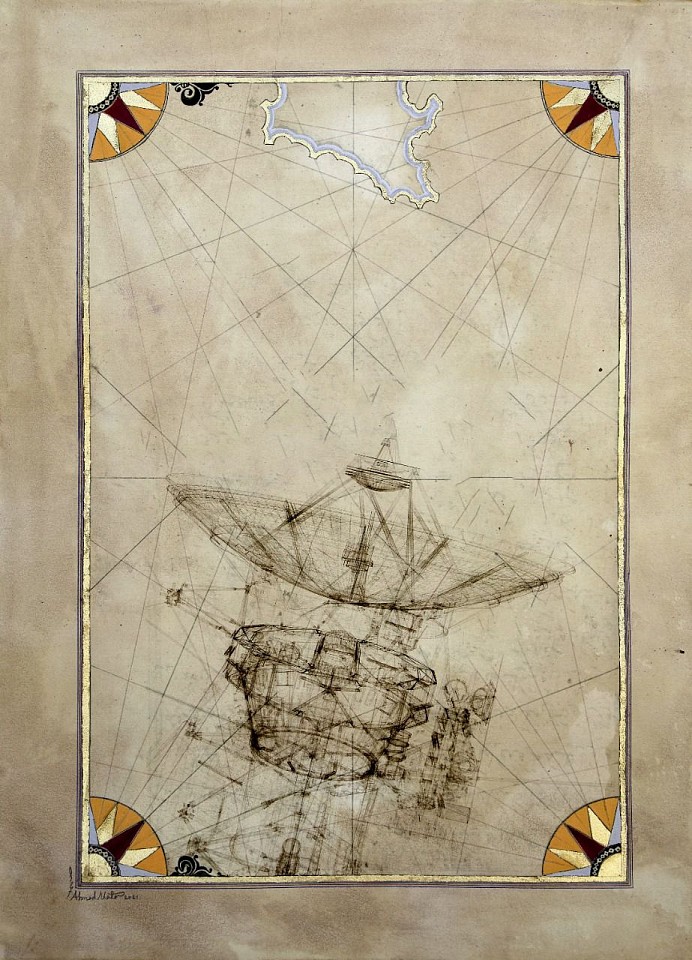

IIllumination Grey Eagle # 2, 2021

Mixed Media

AHM0409

Ahmed Mater

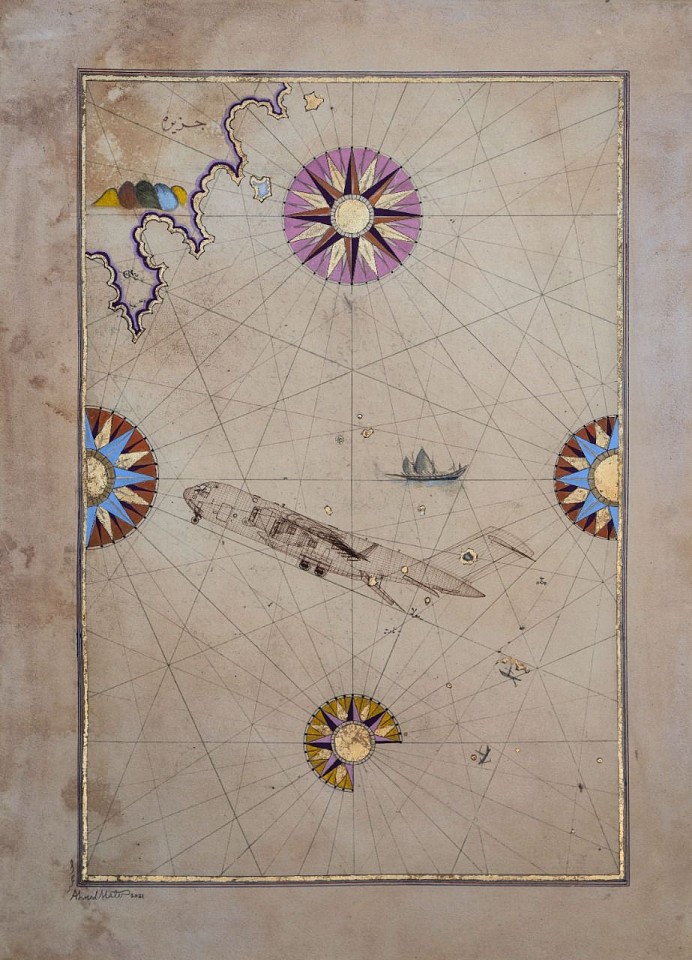

IIllumination Grey Eagle # 3, 2021

Mixed Media

AHM0410

Ahmed Mater

IIllumination Grey Eagle # 4, 2021

Mixed Media

AHM0411

Ahmed Mater

IIllumination Grey Eagle # 5, 2021

Mixed Media

AHM0412

Ahmed Mater

IIllumination Grey Eagle # 6, 2021

Mixed Media

AHM0413

Ahmed Mater

IIllumination Grey Eagle # 7, 2021

Mixed Media

AHM0414

Ahmed Mater

IIllumination Grey Eagle # 8, 2021

Mixed Media

AHM0415

Ahmed Mater

The Eagle, 2021

High density polyurethane and HSL 3d print covered by acrylic one and sand

AHM0417

Ahmed Mater

1973, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0355

Ahmed Mater

Al Malaz, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0356

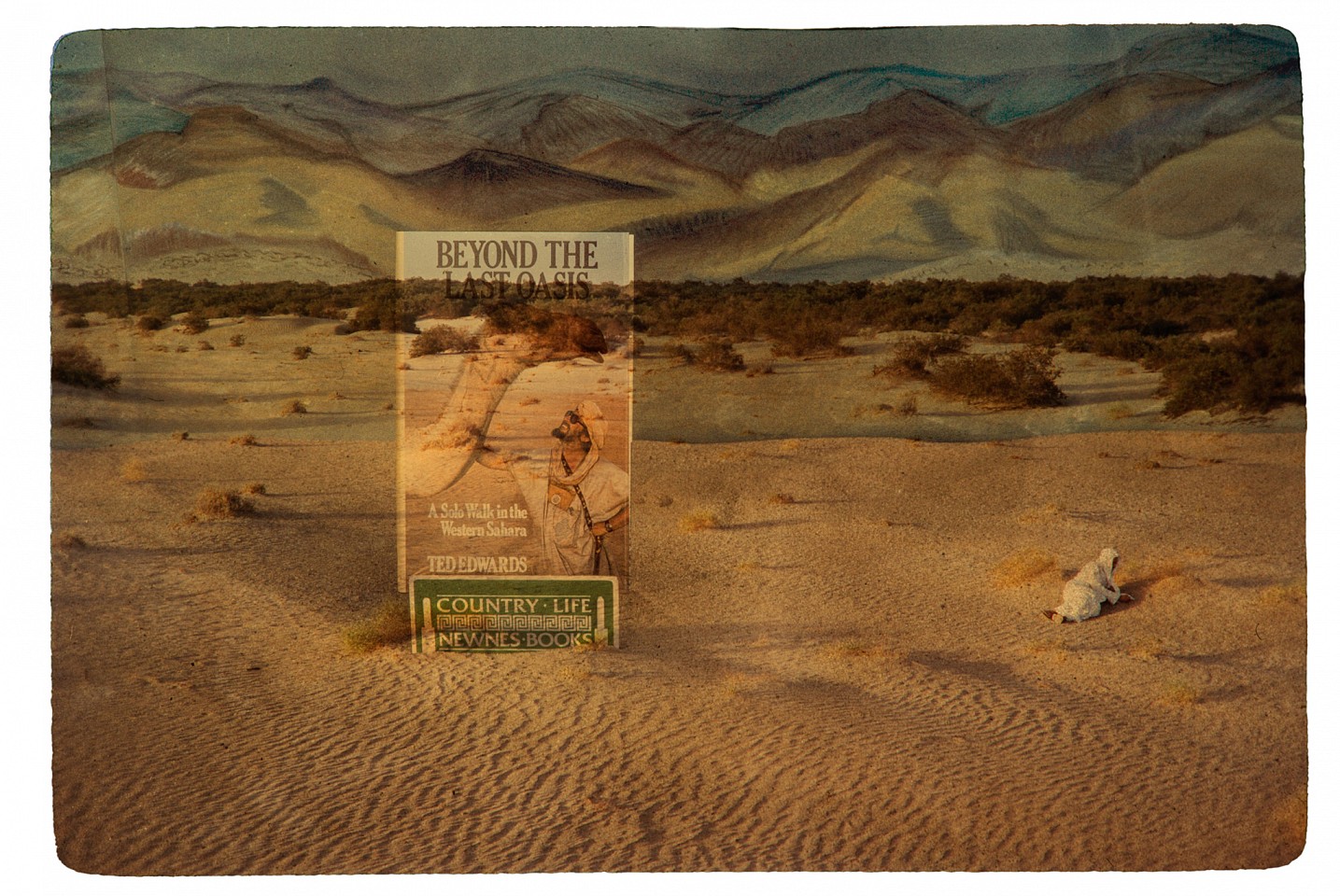

Ahmed Mater

Beyond The Last Oasis, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0354

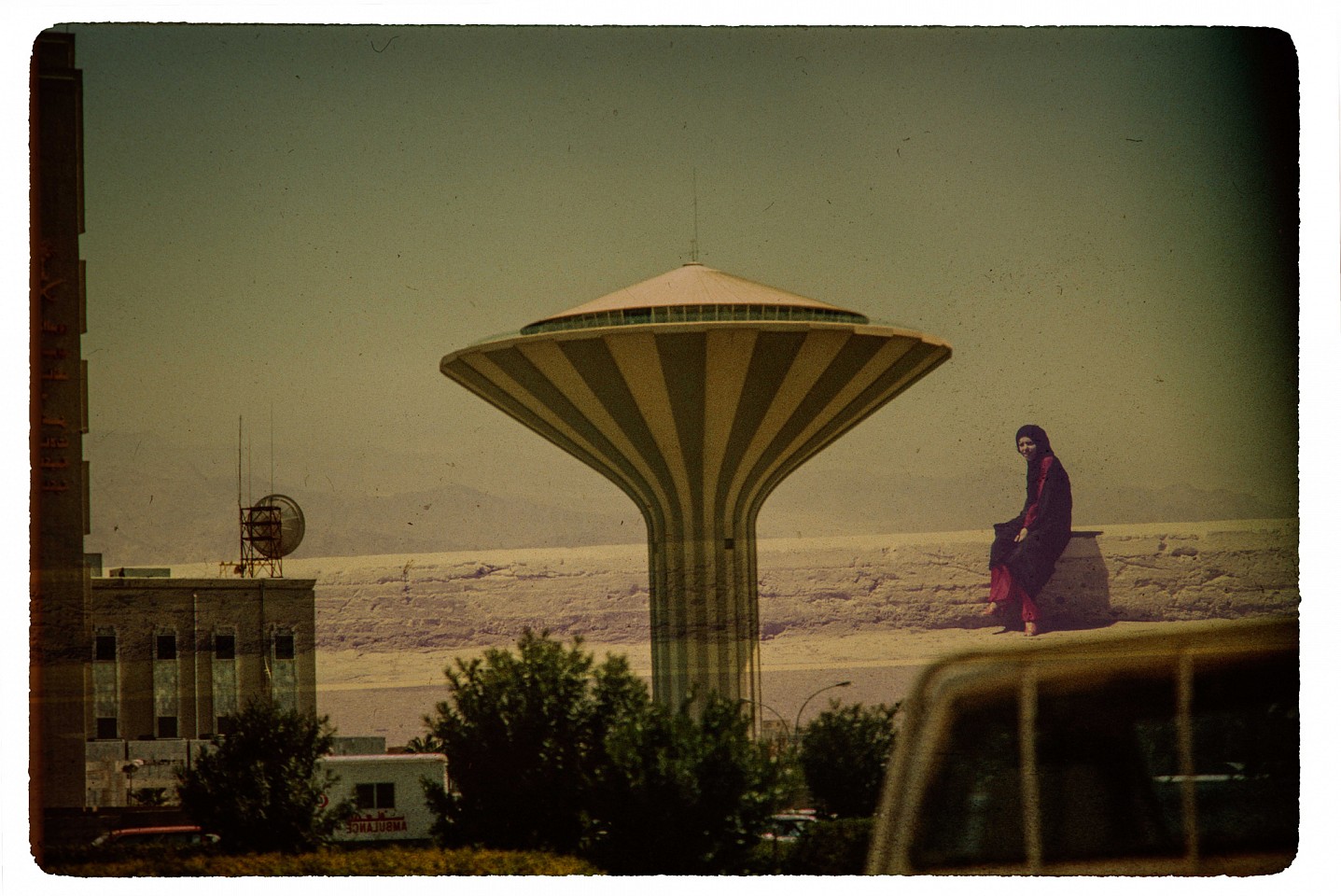

Ahmed Mater

Cadillac, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0359

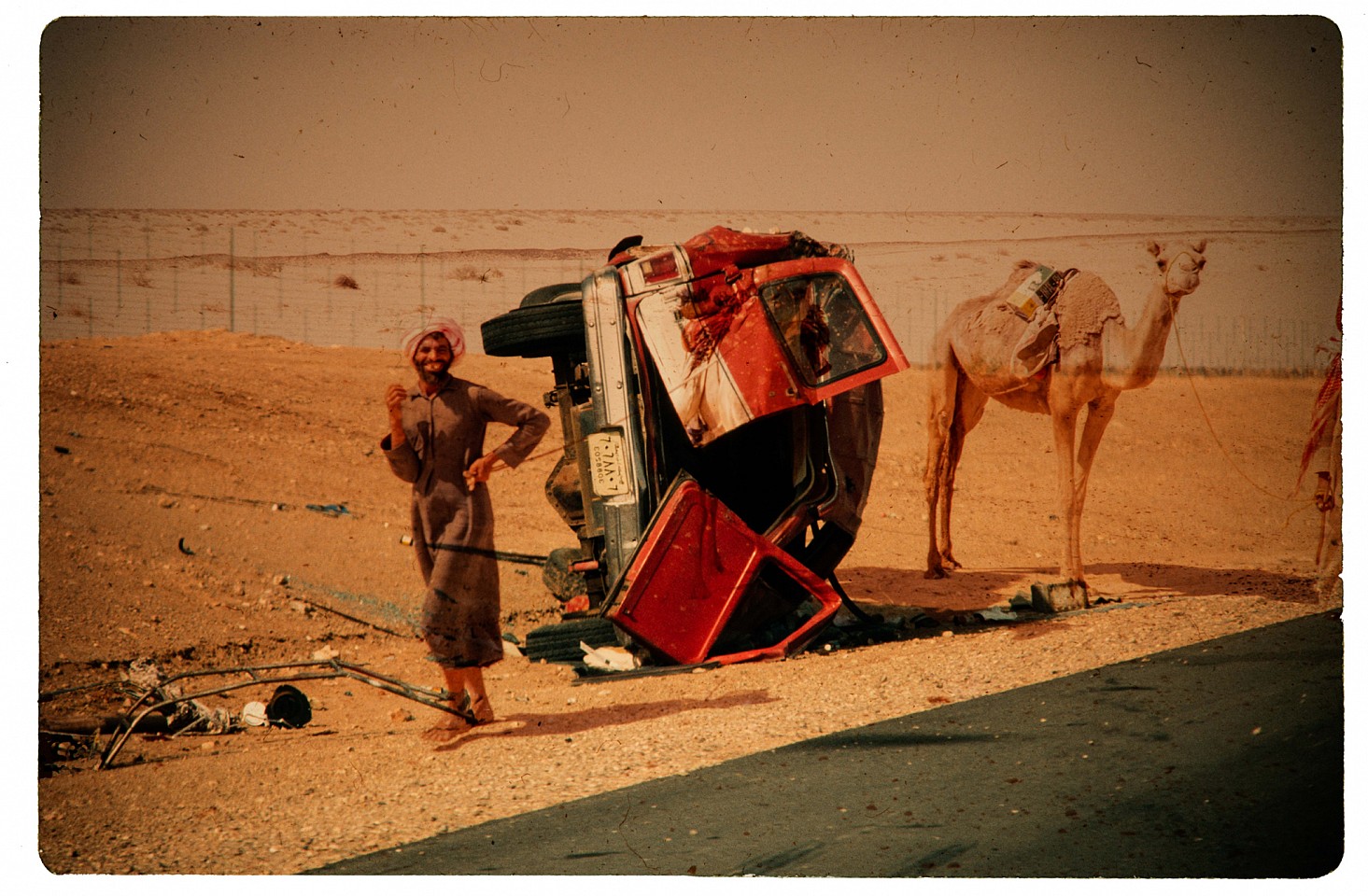

Ahmed Mater

Crash, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0361

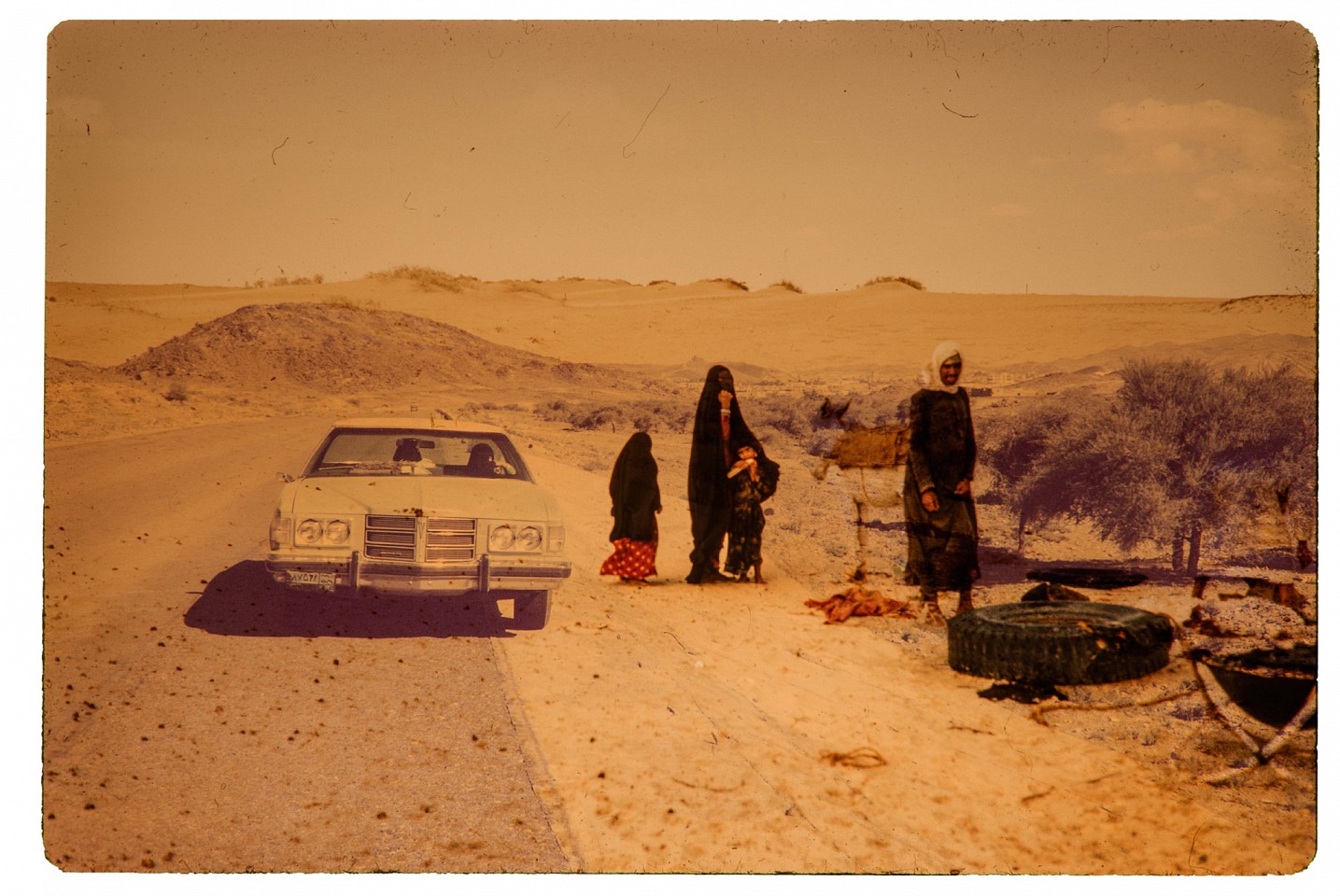

Ahmed Mater

Crisis, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0358

Ahmed Mater

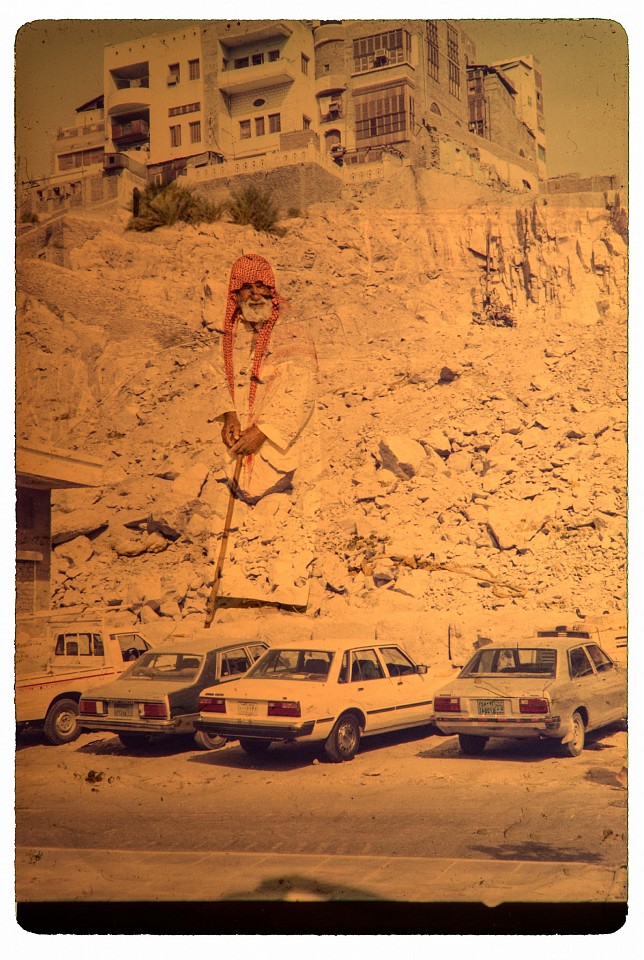

Old Poet, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0360

Ahmed Mater

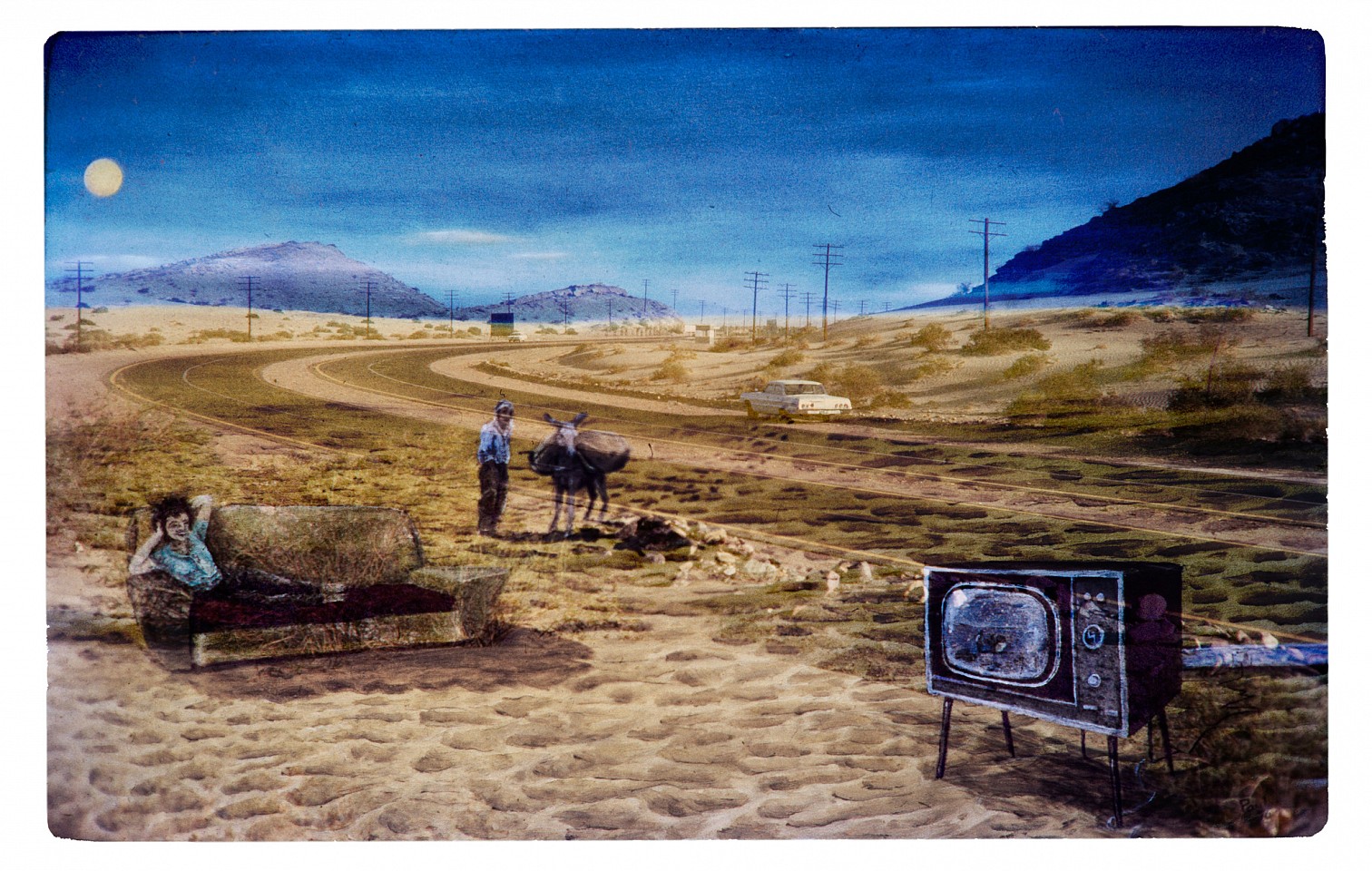

Pipeline, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0357

Ahmed Mater

Roadblock, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0362

Ahmed Mater

Television, 2015

Wood slide viewer with glass slide

AHM0363

Ahmed Mater

Ghost, 2013

Video installation

AHM0344

Ahmed Mater

From Real to the Symbolic City, 2012

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

245 x 292.5 cm (96 1/2 x 115 1/8 in.)

Edition of 3; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0061

Ahmed Mater

Stand in the Pathway and See, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

180 x 140 cm (70 7/8 x 55 1/8 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0048

Ahmed Mater

Yellow Cow Poster (red), 2010

Mixed Media

AHM0310

Ahmed Mater

Yellow Cow Poster (white), 2010

Mixed Media

AHM0308

(Tim Makintosh-Smith) The idea is simple and, like its central element, forcefully attractive. Ahmed Mater gives a twist to a magnet and sets in motion tens of thousands of particles of iron, a multitude of tiny satellites that forms a single swirling nimbus. Even if we have not taken part in it, we have all seen images of the Hajj, the great annual pilgrimage of Muslims to Mecca. Ahmed's black cuboid magnet is a small simulacrum of the black-draped Ka'bah, the 'Cube', that central element of the Meccan rites. His circumambulating whirl of metallic filings mirrors in miniature the concentric tawaf of the pilgrims, their sevenfold circling of the Ka'bah.

Al-Bayt al-'Atiq, the Ancient House, to give the Ka'bah another of its names, is ancient – indeed archetypal - in more than one way. The cube is the primary building-block, and the most basic form of a built structure. And the Cube, the Ka'bah, is also Bayt Allah, the House of the One God: it was built by Abraham, the first monotheist, or in some accounts by the first man, Adam. Its site may be more ancient still: 'According to some traditions,' the thirteenth-century geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi wrote, 'the first thing God created on earth was the site of the Ka'bah. He then spread out the earth from beneath this place. Thus it is the navel of the earth and the mid-point of this lower world and the mother of villages.' The circumambulation of the pilgrims, Yaqut goes on to explain on the authority of earlier scholars, is the earthly equivalent of the angels' circling the heavenly throne of God, seeking His pleasure after they had incurred His wrath. To this day, and beyond, the Ka'bah is a focal point of atonement and expiation; in the Qur'anic phrase, 'a place of resort for mankind and a place of safety'.

Ahmed Mater's Magnetism, however, gives us more than simple simulacra of that Ancient House of God. His counterpoint of square and circle, whorl and cube, of black and white, light and dark, places the primal elements of form and tone in dynamic equipoise. And there is another dynamic and harmonious opposition implicit in both magnetism and pilgrimage – that of attraction and repulsion. The Ka'bah is magnet and centrifuge: going away, going back home, is the last rite of pilgrimage. There is, too, a lexical parallel: the Arabic word for 'to attract', jadhaba, can also on occasion signify its opposite, 'to repel'. ('In Arabic, everything means itself, its opposite, and a camel,' somebody once said; not to be taken literally, of course, although the number of self-contradictory entries in the dictionary is surprising.) And yet all this inbuilt contrariness is not so strange: 'Without contraries,' as William Blake explained, 'there is no progression. Attraction and repulsion . . . are necessary to human existence.'

But Ahmed Mater's magnets and that larger, Meccan lodestone of pilgrimage can also draw us to things beyond the scale of human existence, and in two directions at once – out to the macrocosmic, and in to the subatomic. In the swirl of Ahmed's magnetized particles and the orbitings of the Mecca pilgrims are intimations of the whirl of planets, the gyre of galaxies. Hayy ibn Yaqzan, fictional brainchild of the twelfth-century Andalusian philosopher Ibn Tufayl (and perhaps both a spiritual precursor of the Mevlevi 'whirling dervishes' and a literary ancestor of Robinson Crusoe), made this latent link between terrestrial and celestial tawaf explicit. Looking skyward from the island on which he had been marooned as an infant and had grown to the age of reason, he observed the heavenly bodies - and then began to imitate their orbital motions, 'sometimes walking or running a great many times round about his House or some Stone,' in Simon Ockley's translation of 1708, 'at other times turning himself round so often that he was dizzy.' (In a footnote Ockley, a Cambridgeshire clergyman, thought all this 'extreamly ridiculous'; his Arabic was clearly better than his metaphysics.) And, to pursue the other, inward path, into the microcosm, might not a Hayy ibn Yaqzan born into the age of particle physics find himself equally inspired by the motion of electrons? Magnetism, gravity, attraction-repulsion are necessary not just to human existence, but to the very being of the cosmos; they are what make worlds both large and small go round. Some commentators, like the literary Elizabethan Sir John Davies, have given these forces another name, more poetic but no less apt:

Kind nature first doth cause all things to love; Love makes them dance, and in just order move.

Love is what sets in motion the Mevlevi, whirling in his perfect white corolla of skirts, and the circling planet, and the circumambulating pilgrim, and the subatomic tawaf of the atom that makes it all possible.

Perhaps then this is the conclusion to which Ahmed Mater's Magnetism draws us: that there is a dynamic unity running through creation; that in all things the Creator – 'the ordainer of order and mysticall Mathematicks,' as Dr Thomas Browne (like Dr Ahmed Mater, a creative physician-metaphysician) called Him – has set in balance the forces of pull and push and light and dark, has circled the square, and given exquisite form to inchoate matter. That, at any rate, is my conclusion, and it is why Ahmed's works work for me; both these and the mystical anatomies of his Illuminations. Like good poetry, they speak on a modest and graspable scale of things that are too big or too small or too mysterious to comprehend with the naked mind.

And what of Ahmed Mater himself, giving a twist to the magnet: is there a touch of the demiurge in him - of the creator with a small c? Yes; and one cannot be an artist without that touch.

Look again, and you may also observe in him a touch of the majdhub – literally, 'one who has been attracted'. Here I mean it not in the debased sense it has taken on in many Arabic dialects, that of someone who is a little mad; but in the sense in which it is used in Islamic mystical texts, that of someone who has lost his personal consciousness in the knowledge of the Oneness of God.

Another way to translate it might be, 'magnetized by the divine'.

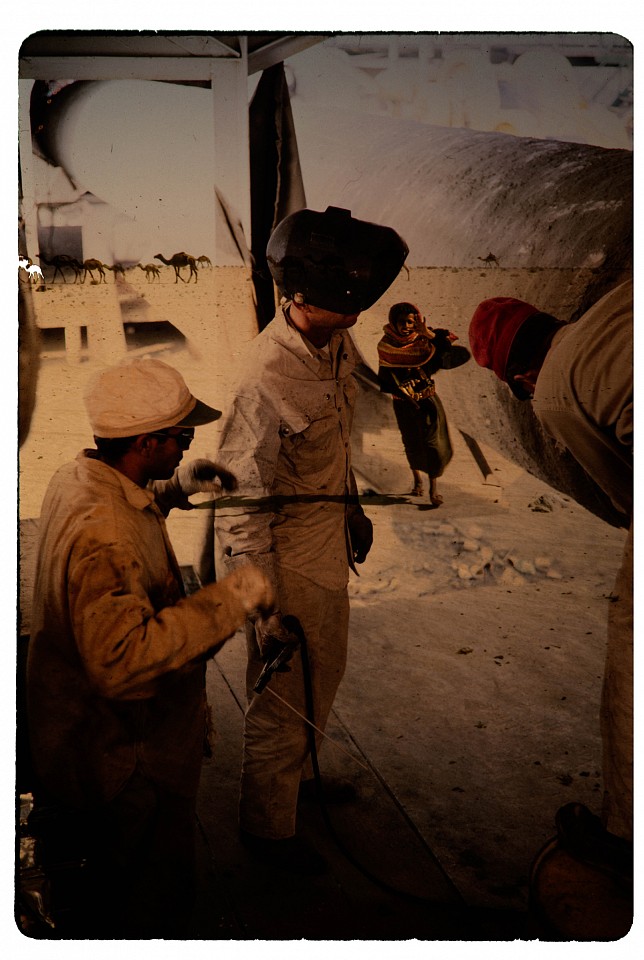

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

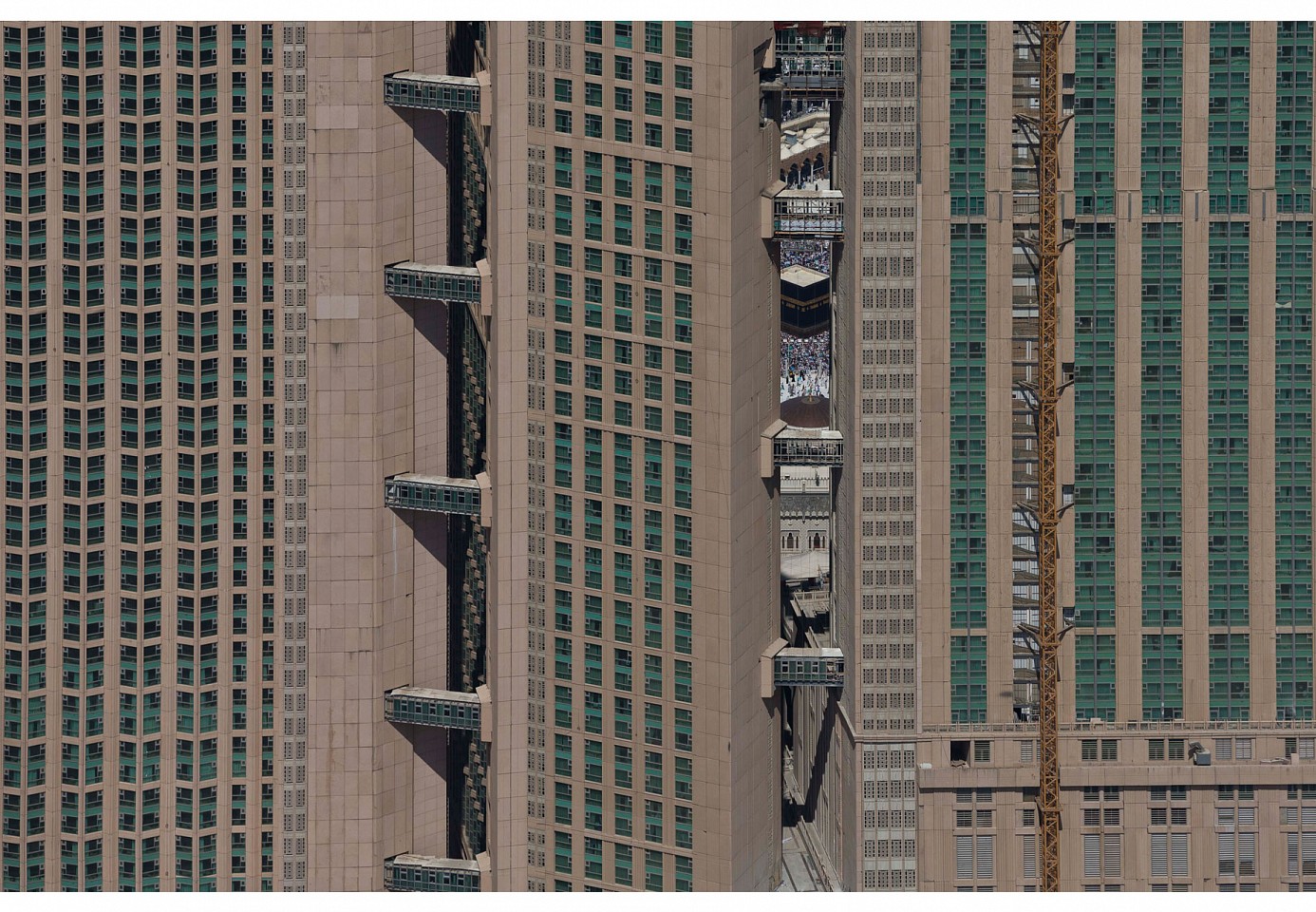

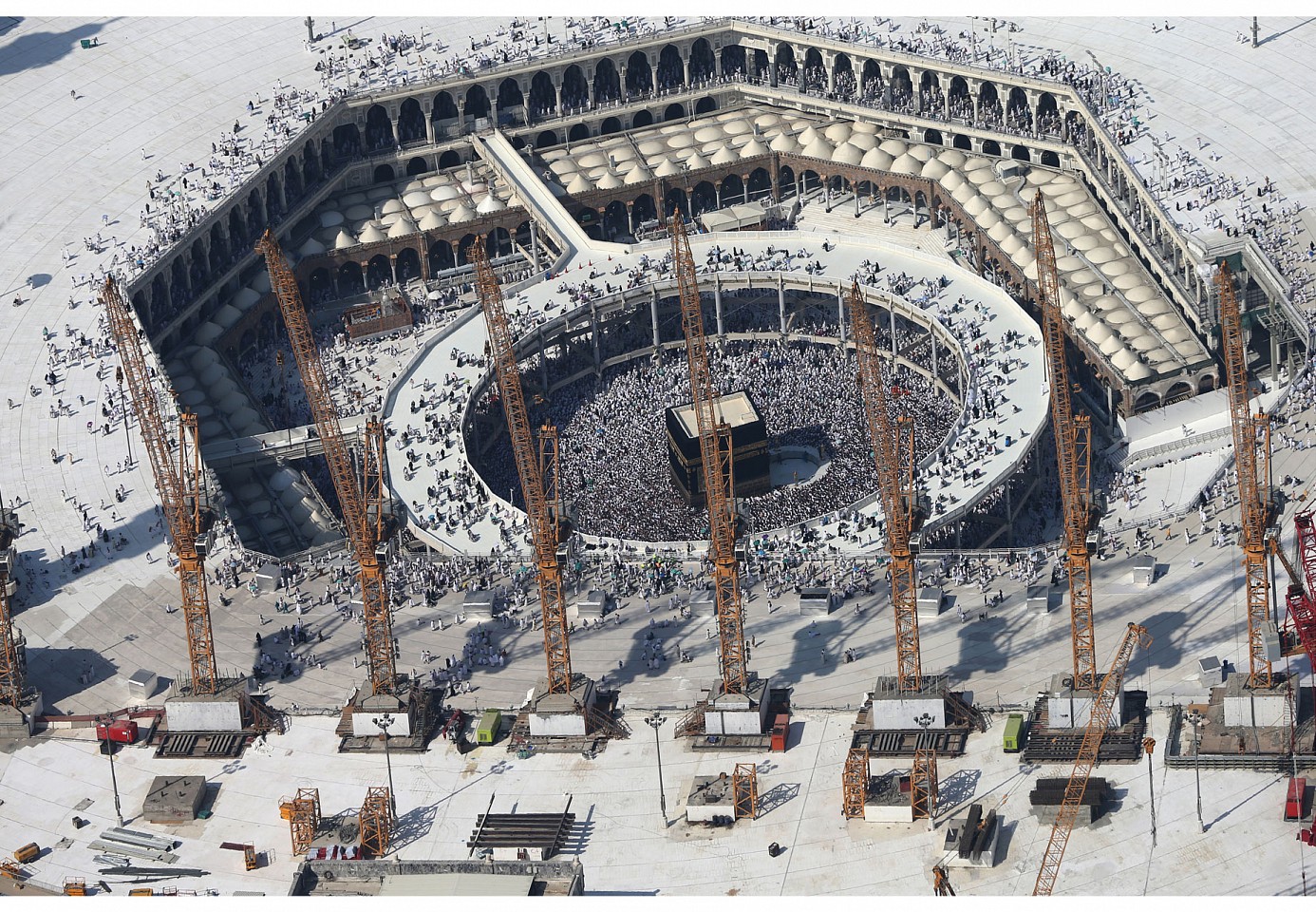

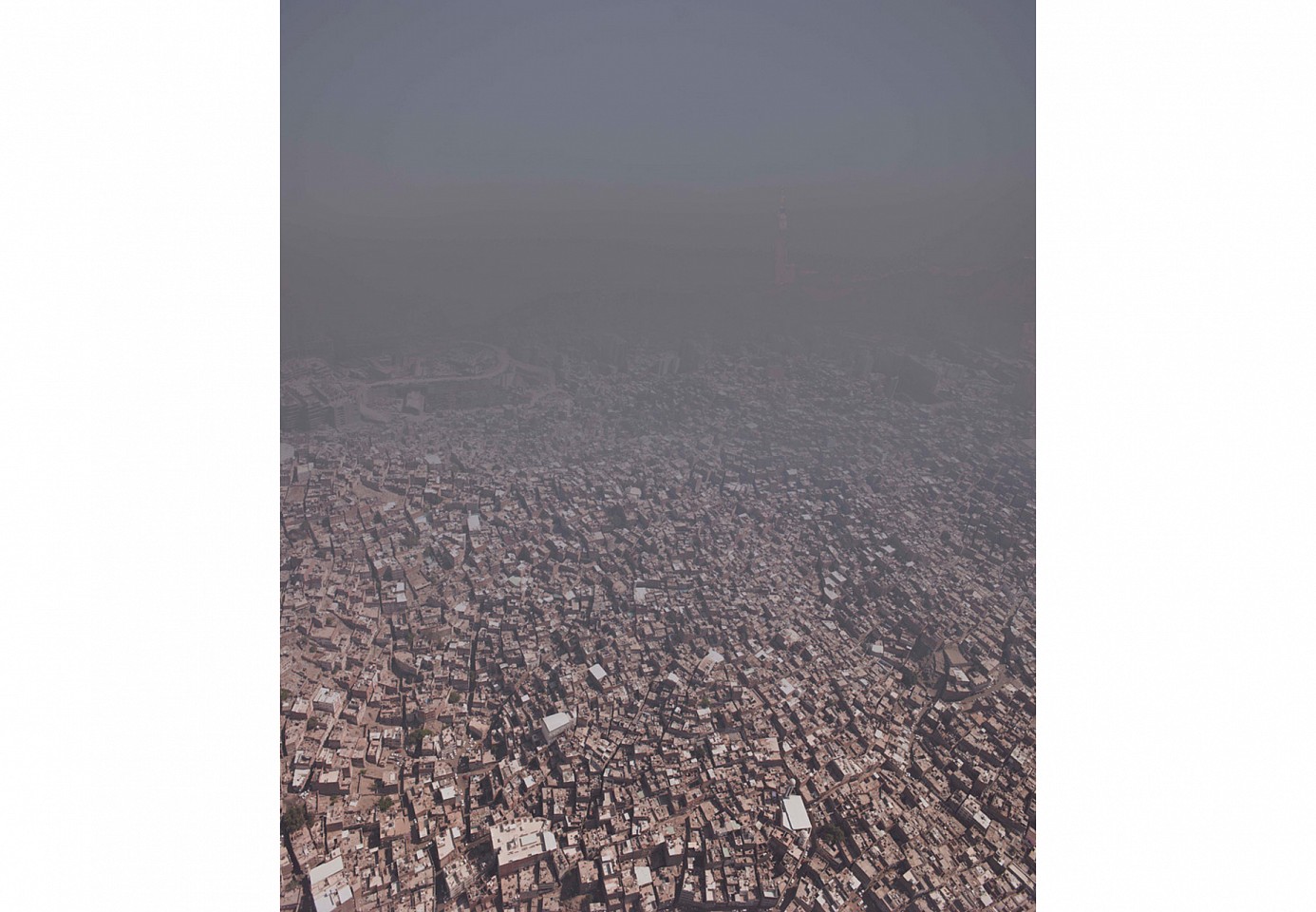

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

-Naima Rashid

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

-Naima Rashid

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

-Naima Rashid

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

-Naima Rashid

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

- Naima Rashid

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

- Naima Rashid

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

- Naima Rashid

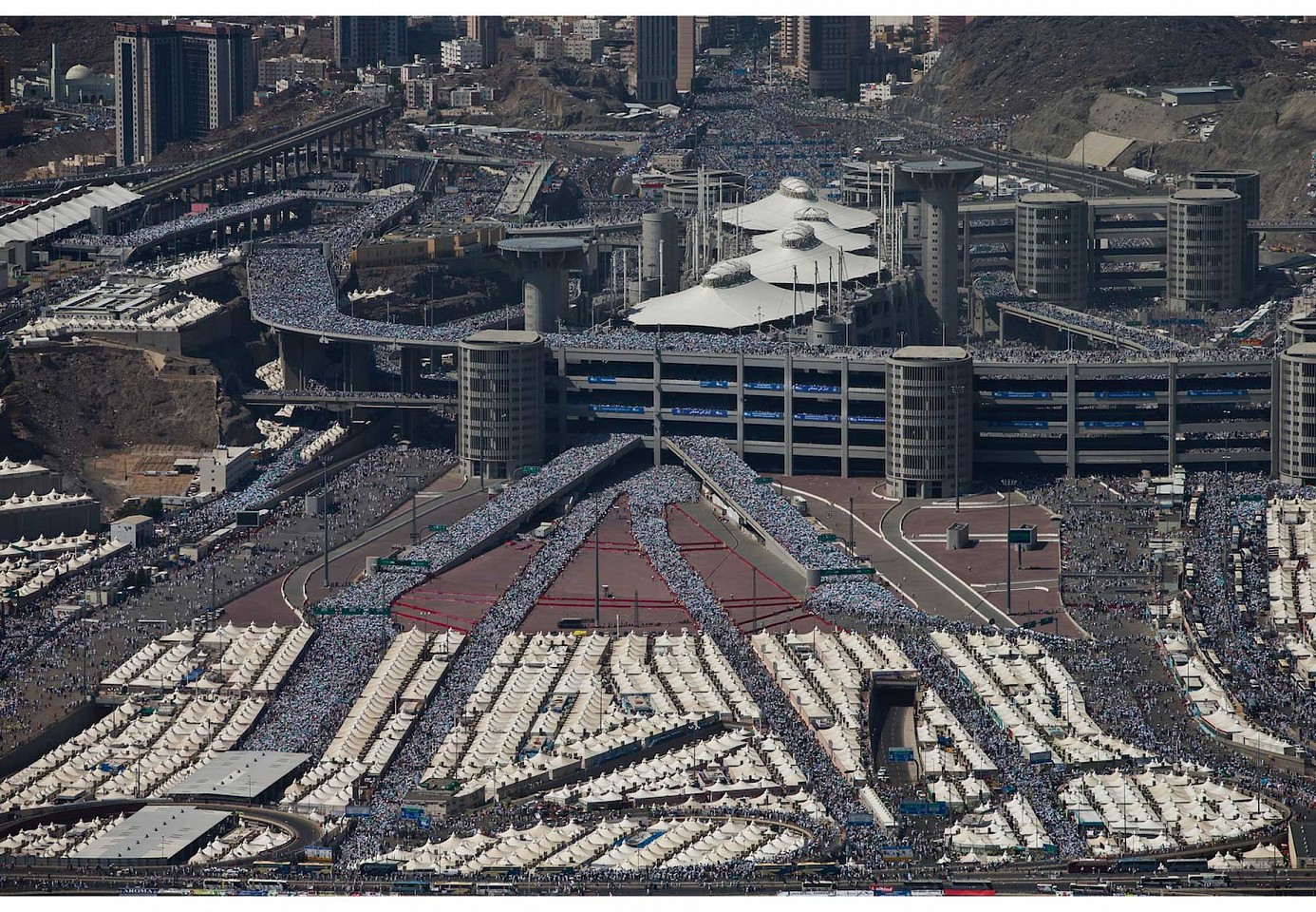

The jamarat, or stone throwing ritual is unique in the Hajj experience, in the sense of what it signifies. The ritual engages the pilgrims to throw seven stones on each of the three pillars, which symbolise pelting the devil, as the story of prophet Abraham and the angel Gabriel goes.

Due to the expansion witnessed by Makkah and the Holy Mosque lately, the jamarat area or pillars have also witnessed a similar progress in construction, looking very different from what it was. What looked liked a passionate yet simple throw of stone towards evil, now looks like something completely different.

On the surface these expansions may seem necessary steps to accommodate the ever-growing number of pilgrims coming to the city. The partially political, partially religious motives are boosted by the appetite of the private real estate sector, which is building gigantic hotels and luxury condominiums around the holy site.

Makkah is rarely seen as a living city with its own inhabitants and its historical development through time. It is almost exclusively seen as a site of pilgrimage, as a timeless, symbolic city. The denial of the real city with its typical urban problems (traffic, lack of public space, infrastructural deficiencies) allows those who preside over its destiny to implement the current plans for massive transformation. The old cosmopolitan city, residue of many centuries of pilgrims choosing to stay in the city and mingle with its inhabitants, is giving way to a new global city populated with immigrant labor, pilgrims/tourists and Muslim businessmen. The symbolic city is replacing the real city.

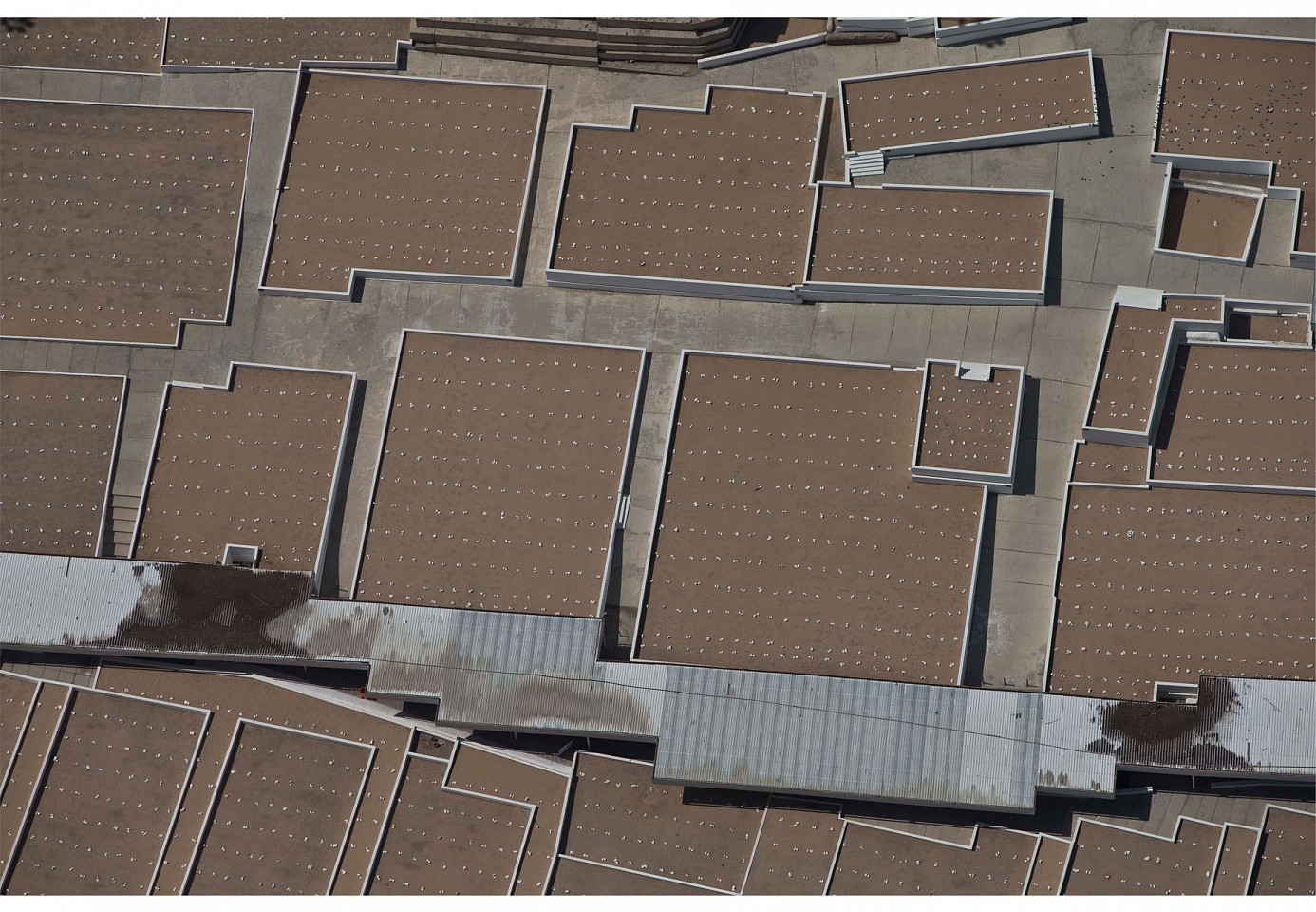

‘Desert of Pharan’ is Ahmed’s artistic response to these developments. “Pharan” is taken from the Quran, as the area around Makkah was called like this in the ancient days. Using the latest in photographical technology Ahmed has documented many aspects of the city’s transformation, from the experience of the construction workers to images of the new Mosque in construction, from the luxury hotels ‘with a private view on the Ka’aba’ to the streets and public festivities in the city. And in October 2012 he documented the Hajj, from helicopters, motorcycles and fixed vantage points above the crowds, but also by participating as a simple pilgrim.

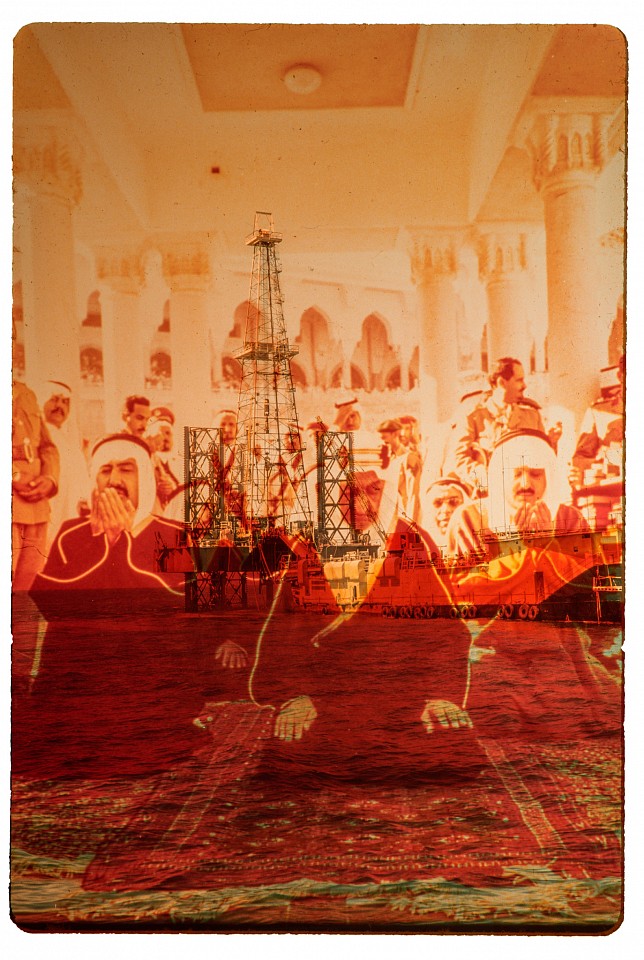

Saudis, by and large, do not believe in the theory of evolution. Like other conservative, religious societies, Saudis have firmly rejected Darwin’s theory on the basis that human beings are perfect, state-of-the-art creations, not the result of some natural process. Ahmed Mater is a doctor by training. He believes in evolution. But for him, evolution does not necessarily mean survival of the fittest. Sometimes, evolution can lead to one’s demise. Saudi Arabia, founded in 1932, was a poor country with scarce natural resources. Then in 1938 oil was discovered in its deserts, and ten years later production was up to full capacity. Petrodollars flooded the Kingdom, transforming the face of its land and giving Saudi a great deal of leverage with the international community. Interestingly, the origin of oil is connected to the theory of evolution. Oil is derived from ancient organic matter; the remains of creatures that have not survived the planet’s biological and geological changes. Saudi Arabia did not only use petrodollars to fuel its rapid development; vast amounts of the same money were also used to promote and spread the Saudi conservative interpretation of Islam, also known as Wahhabism. But most Saudis reject this term because they believe they are simply practicing Islam in its purest form, and also because they think the term has been used unfairly to slander their religion and their country. Whether they agree with the term or not probably matters little now, because some of the ideas that originated in Saudi have, in recent years, come to shake the world. Most people will read Evolution of Man as an unabashed critique of humanity’s dependence on oil, and what ‘black gold’ represents to those living above the reserves. But Evolution of Man is more than just a political statement. As Ahmed Mater explains,

“I am a doctor and confront life and death every day, and I am a country man and at the same time. I am the son of this strange, scary oil civilization. In ten years our lives changed completely. For me it is a drastic change that I experience every day.”

The chronological timeline is also fluid, it’s not like a train with separate compartments but like a river with different flow points, and a constant back and forth circuit of energy and waters that feed, renew, invigorate and intersect each other. Crossing over time and space, Cowboy Code, Mater’s most recent work, harkens to the minimalism of Joseph Koluth’s work based on textual definitions of concepts; almost doing away with the very dimension of aesthetics. Pure, unadulterated concept, the installation consists of a text in the form of ten commandments written on a scroll composed of plastic baby gun caps. The code is an appropriation of a song initially coined by Gene Autry in the 40s.

I am stealing it back for my purpose, and releasing it into the life of my people because I think they need it now. Somebody else might steal it back from me in their turn.’ It is an attempt to realign behavior along the lines of classic, almost universal appeal; the timeless character of the vagabonding cowboy-playful and frivolous on the outside and apparently sans attaches, but with an almost inviolable moral core. The cowboy is the nomad of the western sands, like the Bedouin is the nomad of the Eastern sands. “I’m not creating it. The code already exists. The moral sense exists inside all of us. The example exists, the fact exists. I’m just showing the way by bringing in a catchy example from the past so people can engage with the work. This engagement is my reward.” Seeking what unites us rather than what sets us apart: ‘The Cowboy Code’

A Boy Stands on the flat, dusty rooftop of his family’s traditional house in the south west corner of Saudi Arabia. With all his reach he lifts a battered TV antenna up to the evening sky. He moves it slowly across the mountainous horizon, in search of a signal from beyond the nearby border with Yemen, or across the Red Sea towards Sudan. He is searching, like so many of his generation in Saudi, for ideas, for music, for poetry – for a glimpse of a different kind of life.

His father and brothers shout up from the majlis (sitting room) below, as music fills the house and dancing figures appear on a TV screen, filling the evening air with voices from another world. “This story says a lot about my life and my art” Ahmed tells me, as he installs a bright, white neon antenna into the ceiling of a warehouse gallery in Berlin. “I catch art from the story of my life,” he continues. “I don’t know any other way.”

Ahmed Mater is the boy with the antenna; a young explorer in search of contact with the outside world, reaching out to communicate across the borders that surround him. It is this spirit of creative exploration and curiosity that defines Ahmed’s journey as an artist.

Ahmed Mater’s The Cowboy Code (2012), is a large-scale wall based installation of ten commandments, listed in Arabic and English using plastic toy gun caps. The commandments or codes are an appropriation of a song first performed by Gene Autry in the 40s.

The timeless character of the vagabonding cowboy is a persona once present throughout the pictures houses of Mater’s youth – a playful and frivolous character on the outside but with an almost inviolable moral core. For Mater, the cowboy is the nomad of the Western sands, much like the Bedouin is the nomad of the Eastern sands. Through this work, the artist is seeking out what unites ‘us’ (East and West) rather than what sets us apart. He makes comparisons between the language of two codes of ethics, one from the American West and one from the Islamic code referring to statements or actions of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), known as the Hadith.

“When we were children, we often played with toy guns, and would buy the little red caps from the local shop. They were called ‘Western Gun Caps’. You could get them everywhere in Saudi Arabia. We imitated the cowboys we saw on television. Their language, their clothes, their values.”

The Cowboy Code

1 A cowboy never takes unfair advantage – even of an enemy.

2 A cowboy never betrays a trust. He never goes back on his word.

3 A cowboy always tells the truth.

4 A cowboy is kind and gentle to small children, old folks, and animals.

5 A cowboy is free from racial and religious intolerances.

6 A cowboy is always helpful when someone is in trouble.

7 A cowboy is always a good worker.

8 A cowboy respects womanhood, his parents and his nation’s laws.

9 A cowboy is clean about his person in thought, word, and deed.

10 A cowboy is a Patriot.

The Hadith (Translation)

1 The Prophet cautioned to always march in the name of God.

2 He cautioned to always march in the path of God.

3 He cautioned never to be extreme or fanatic.

4 He cautioned never to desecrate the bodies of your fallen enemy.

5 He cautioned never to take unfair advantage of your enemy.

6 He cautioned never to harm the elderly.

7 He cautioned never to harm children.

8 He cautioned never to harm women.

9 He cautioned never to harm holy men.

10 He cautioned never to cut down trees.

“Over the course of ten years, our lives changed completely. It is a drastic change that I experience every day. The Cowboy Code is something I have thought about for years. When I was a child, the cowboy was always a symbol of freedom and adventure, an ideology that came from the West and assimilated itself into my culture. Like many of my generation, I have taken a lot from the West – the food we eat, clothes we wear, even our language and so I wanted to present this code as a way of reclaiming these qualities as opposed to purely commodity driven influences. I want to move these compatible beliefs away from the politics, from the media and give them back to the people.”

-Ahmed Mater

View Master slides 1960-80 / 1980-2000 and 2000-2020

Images taken from Makkah’s most widely circulated pilgrim keepsake. Made in China since the pre-1960s they have been shipped over in their thousands along the same silk route that has been central to cultural interaction from East to West since 206 BCE. These same View Finders, once bought on Al Khalil Road in Makkah, are then disseminated through the hands of the pilgrims to every corner of the world. The View Finders and their images, are not only visual portals to a city that bristles under the weight of its own dramatic symbolism but a reflection of a site revered by millions created with the specific task of triggering fantasies of a pilgrimage to Makkah and all it implies. As objects, the View Finders embody these dreams, whilst the collection of images, once released from the limitations of their intended form, are transformed. They become not only social documentation but pertinent and poignant signifiers of specific times and places, drawing on collective history, iconography and memory, of a site that is at once the most visited yet the most exclusive in the world.

Yellow Cow is a series of interventions, performances and installations inspired by a passage in the Surah Al- Baqarah (The Cow), which is the longest chapter in the Qur’an. Mater explains, “The stories I heard in the Qur’an study group were the main stories of my daily life. They were like a guide.”

Yellow Cow is not a work of art that seeks resolution. It is an ongoing project that literally and figuratively places this ancient story into contemporary consumer society. To date, the project has been realised as a film, a shop installation, a brand and a series of products, all asking the same question posed by the story in the Qur’an: what is so special about this yellow cow?

YELLOW COW PERFORMANCE: Ahmed conceived his first Yellow Cow performance just to see how people would react. He went to a farm and, using saffron-based dye, coloured a white cow yellow before setting it free in the village. He then watched the delighted reactions of the villagers, which reminded him of the stirrings of his own imagination as a child in the mosque.

YELLOW COW BRAND: Believing the Yellow Cow was as relevant now as it has ever been, Ahmed decided to “set the story free.” He wanted to release the messages held within the Surah – kept alive in mosques and Qur’anic study groups for 1300 years – into the contemporary world. In order to make the story relevant to people’s lives in the 21st century, he created a brand and initiated a ‘line extension’ of mass-produced Yellow Cow cheese, butter, yoghurt and milk products – flooding the market and giving it a material presence in people’s homes, workplaces and local shops.

Ahmed explains, “In biblical and Quranic times a story was spread by word of mouth and recitation; to spread a story… or an ideology… in the contemporary world, one has to conceive a brand which will be recognizable in the marketplace.”

Heading southeast out of Mecca, Mater encountered ceremonial drummers at a traditional wedding. Following the ebb and flow of one drummer's trance-like state, Mater remembered ominous tales of jinn, the restless spirits that live in the desert near " The dead city of Jahura ... midway between between the borders of Hejaz and Oman. There the sounds of drumming and moaning are regularly heard at night by passing travelers, by whom they are of course attributed to jinns or ghosts, persons of weak intellect having even been known to lose their reason." (Harry St.John Philby, Heart of Arabia: A Record of Travel & Exploration, 1922)

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

- Naima Rashid