Aya Haidar

Aya Haidar

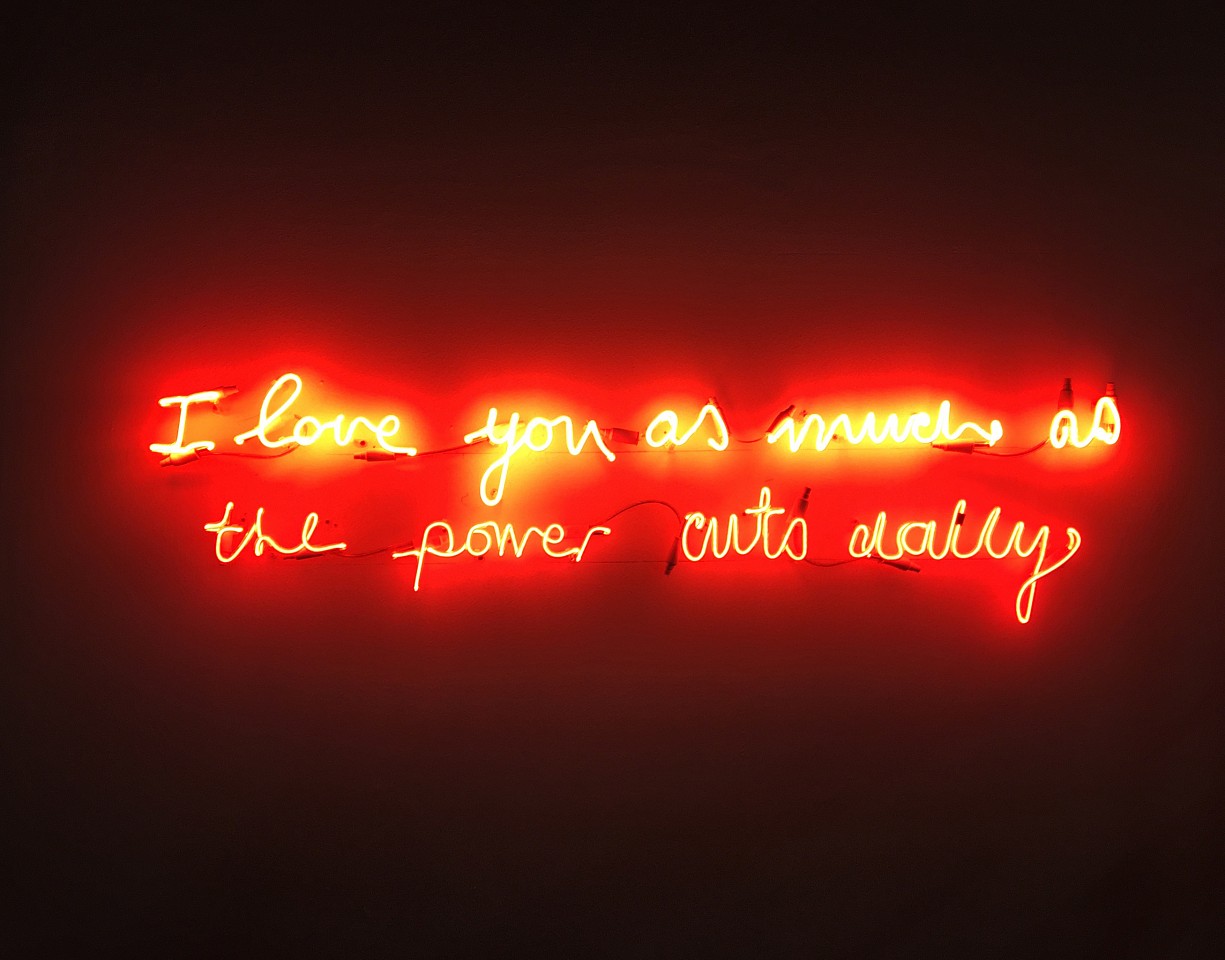

i love you as much as the power cuts daily, 2019

Neon Installation

35 x 150 cm

Aya Haidar

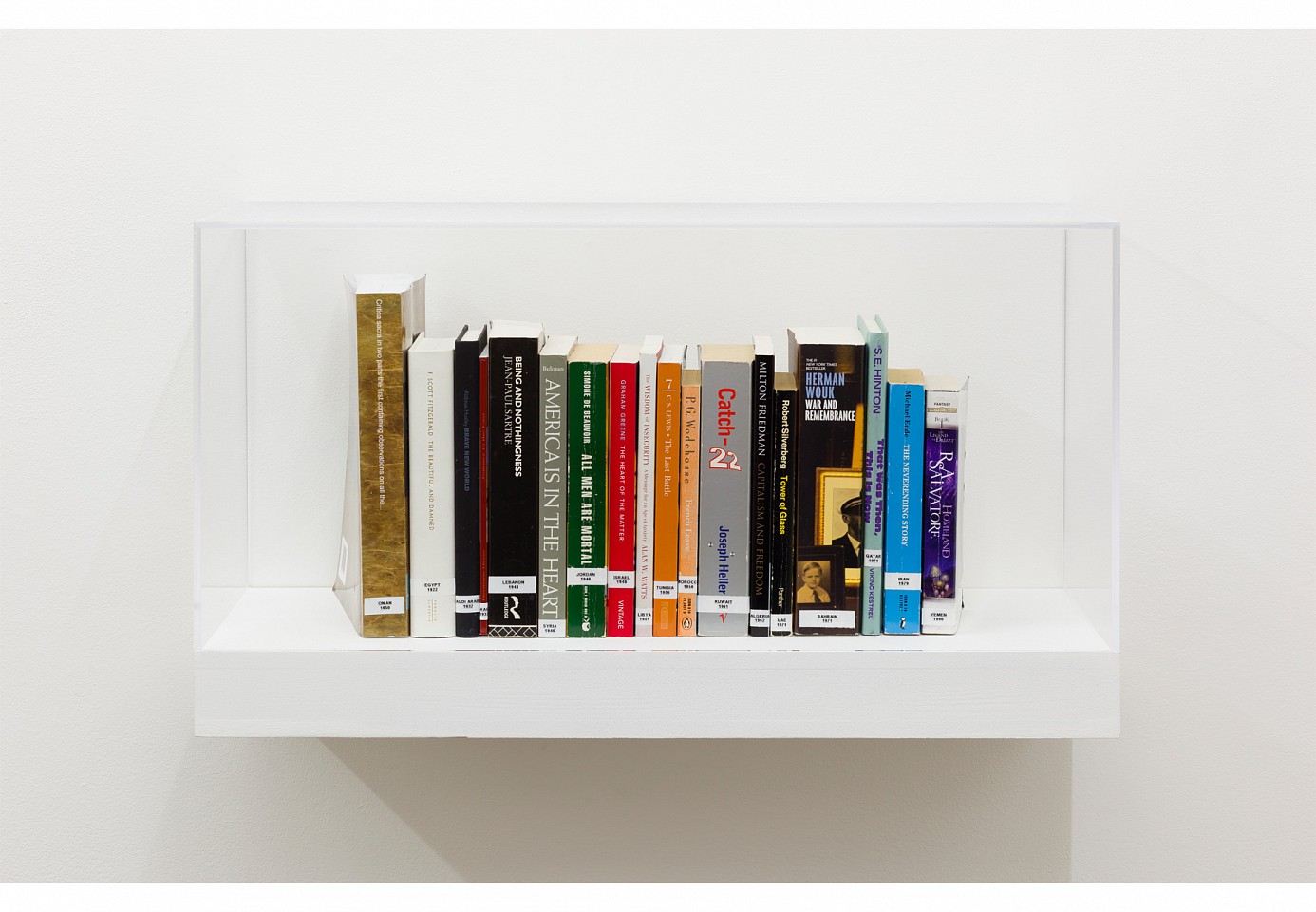

Year of Issue, 2013

Books, Shelf, Perspex

36 x 63 x 25 cm (14 1/8 x 24 3/4 x 9 13/16 in.)

AYH0008

Aya Haidar

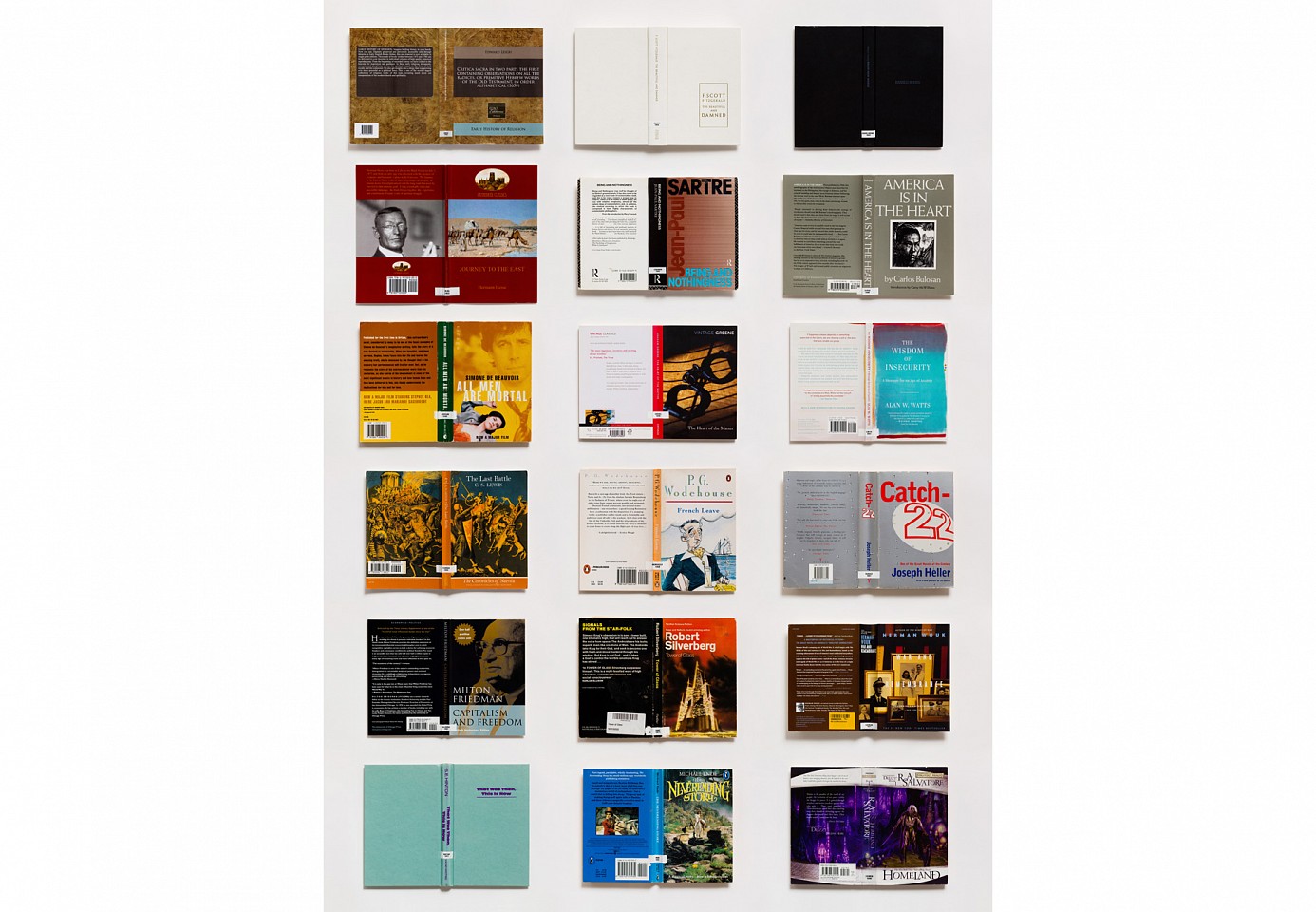

Covered Issues, 2013

Doctored book covers

170 x 125 cm (66 7/8 x 49 3/16 in.)

Edition of 3

AYH0013

Aya Haidar

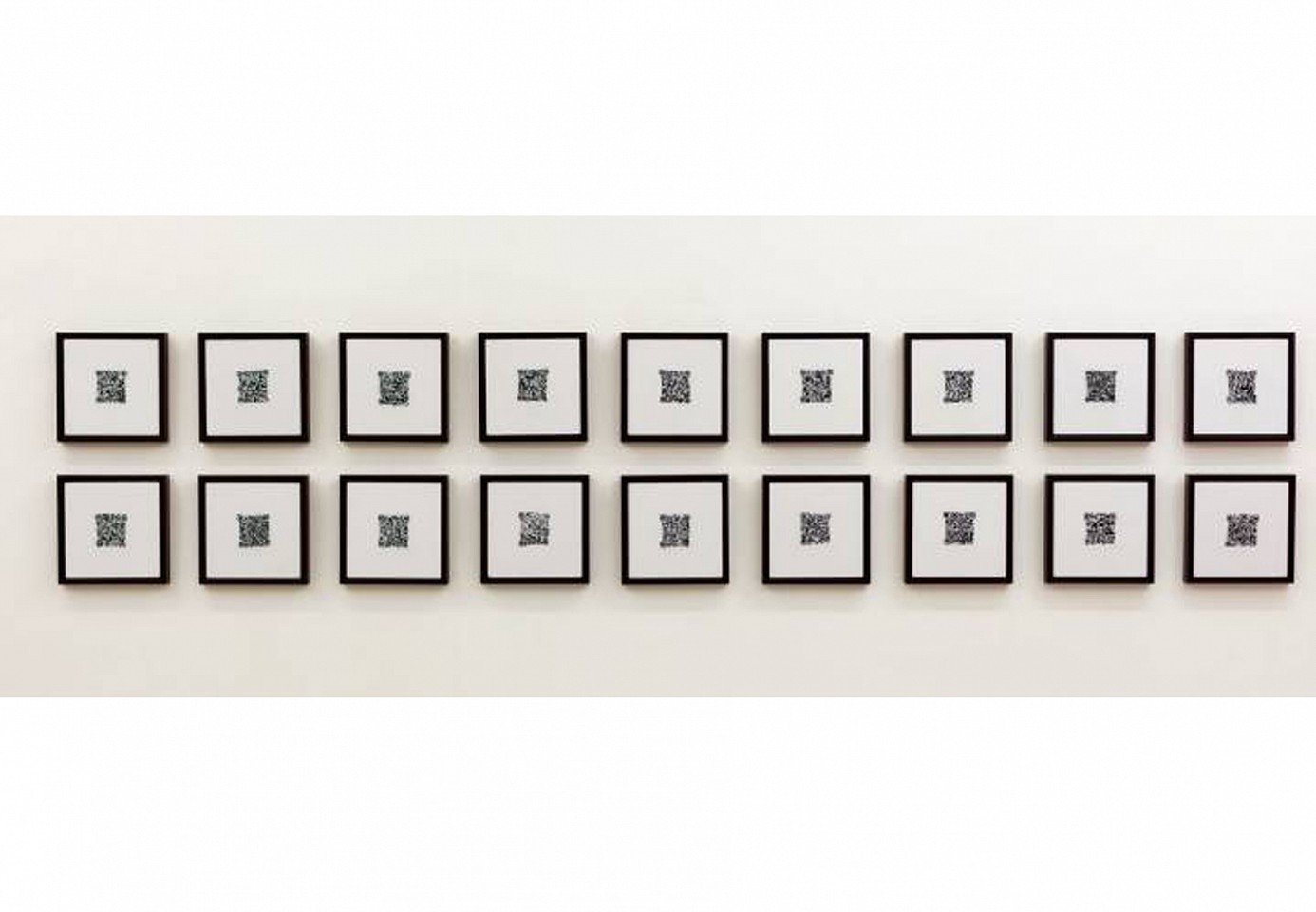

Declaration, 2013

Embroidery on Egyptian cotton

23 x 23 cm (9 x 9 in.)

Edition of 3

AYH0010

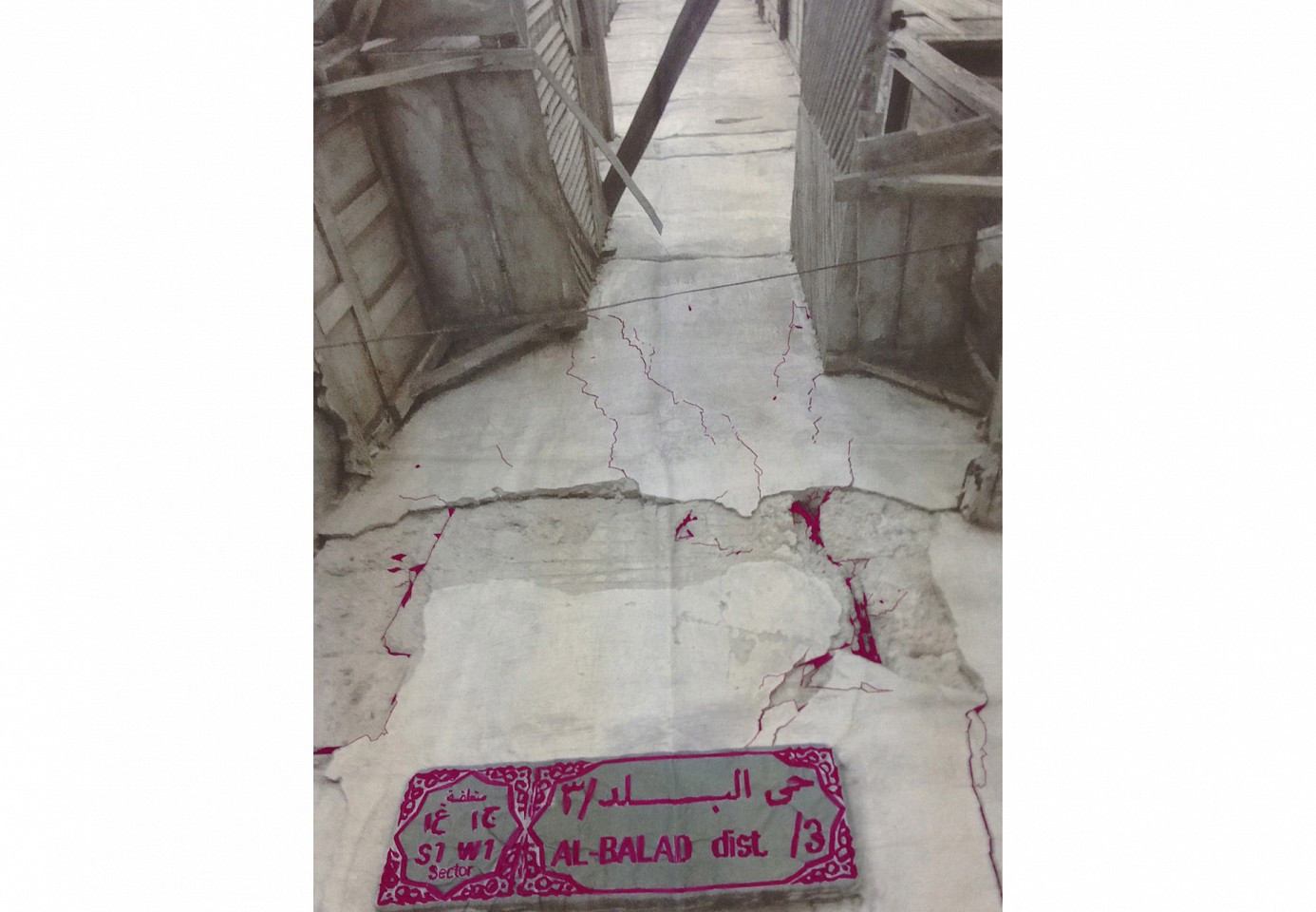

Aya Haidar

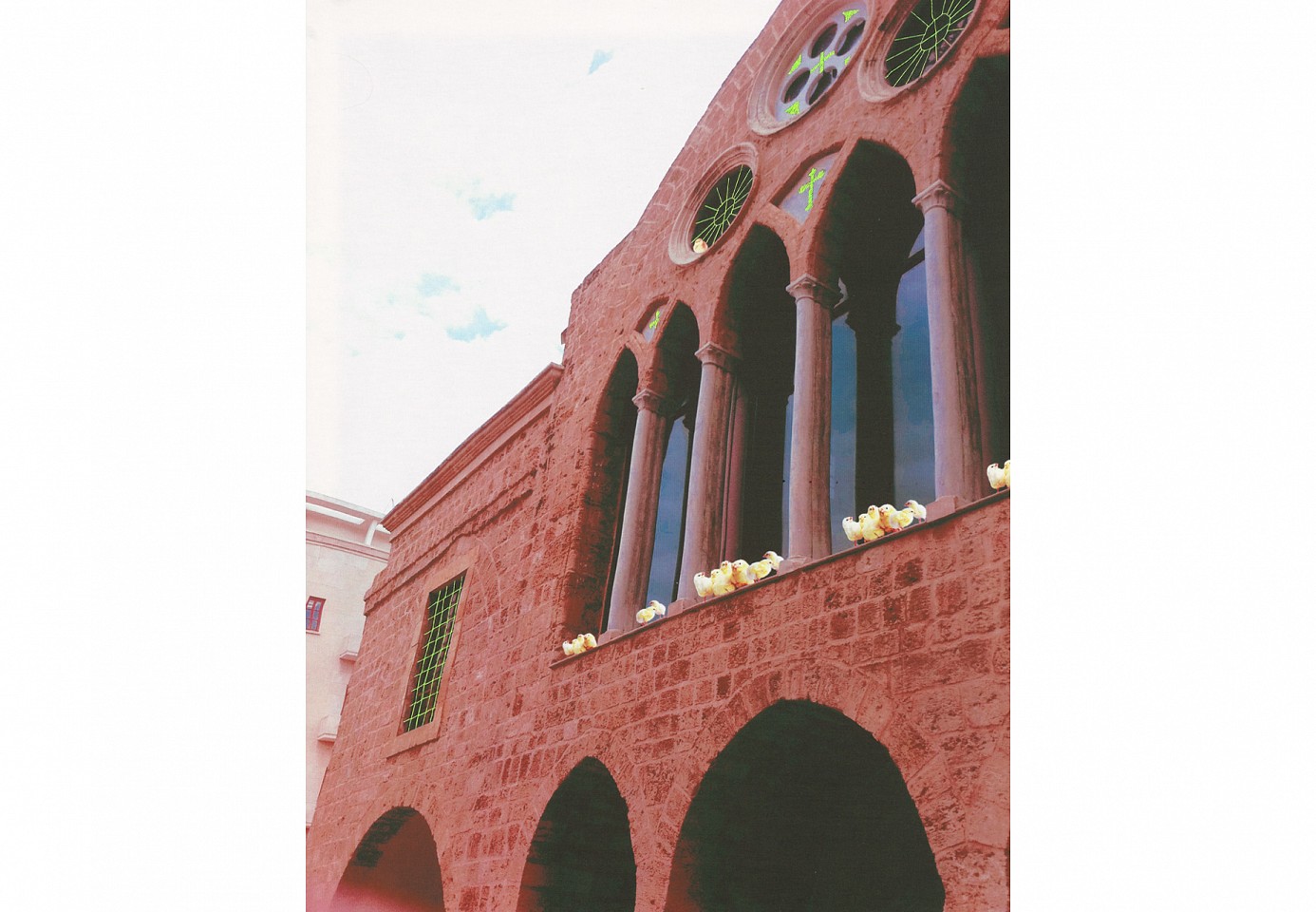

Al Balad XI, 2012

Embroidery on printed linen

122 x 92 cm

From AlBalad Series

AYH0026

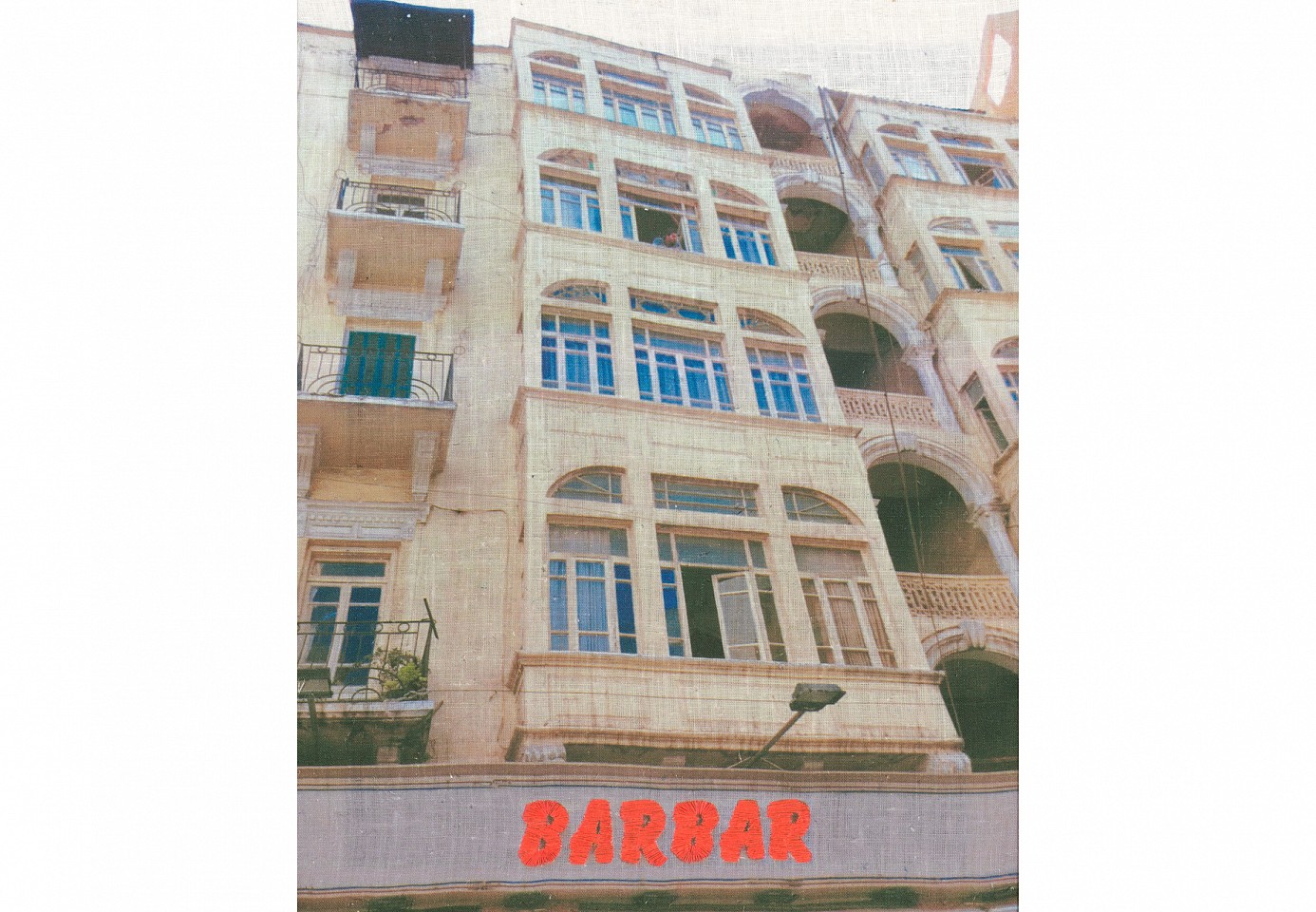

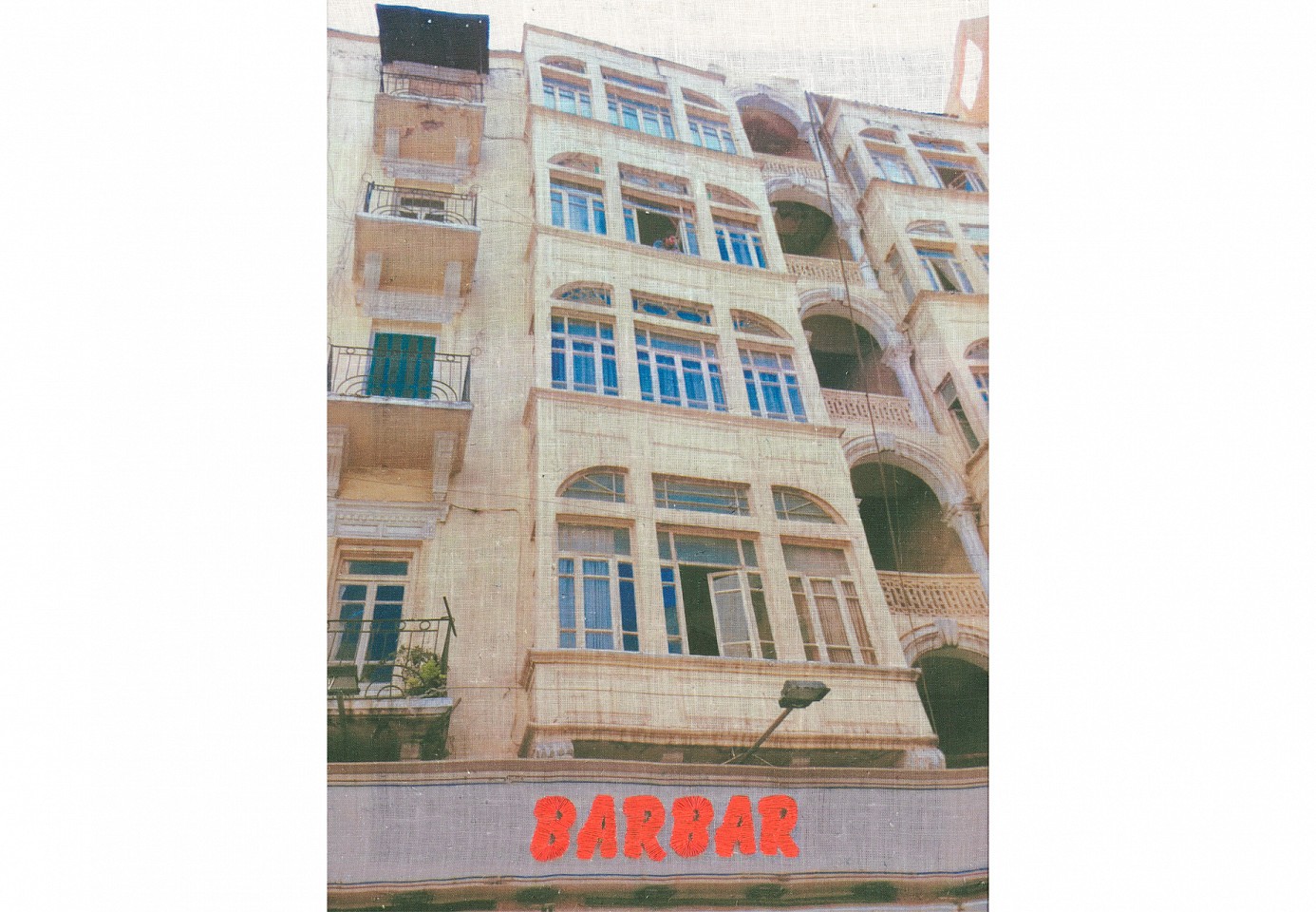

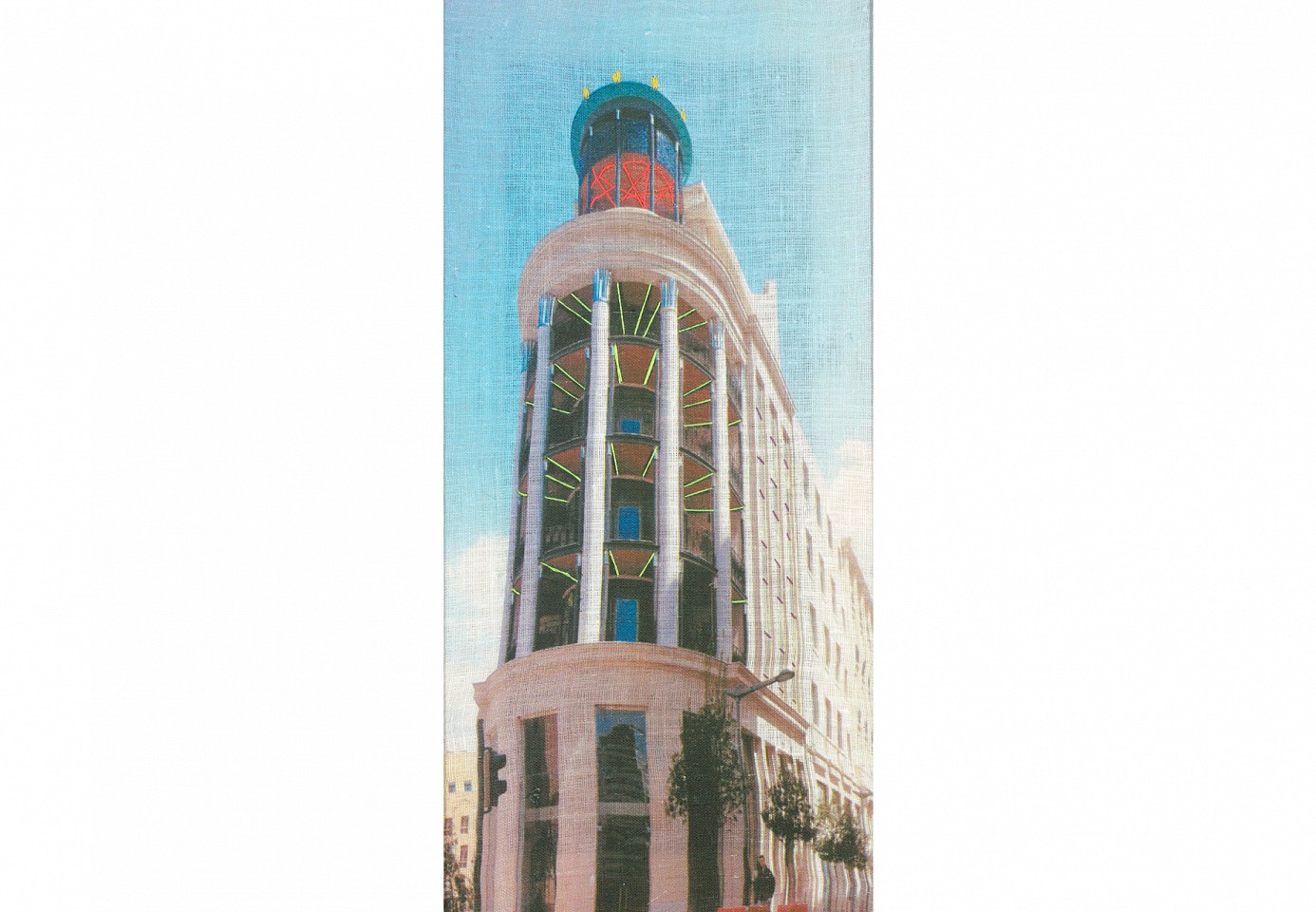

Aya Haidar

Al Balad XX, 2012

Embroidery on printed and starched linen

97.5 x 74 cm

AYH0059

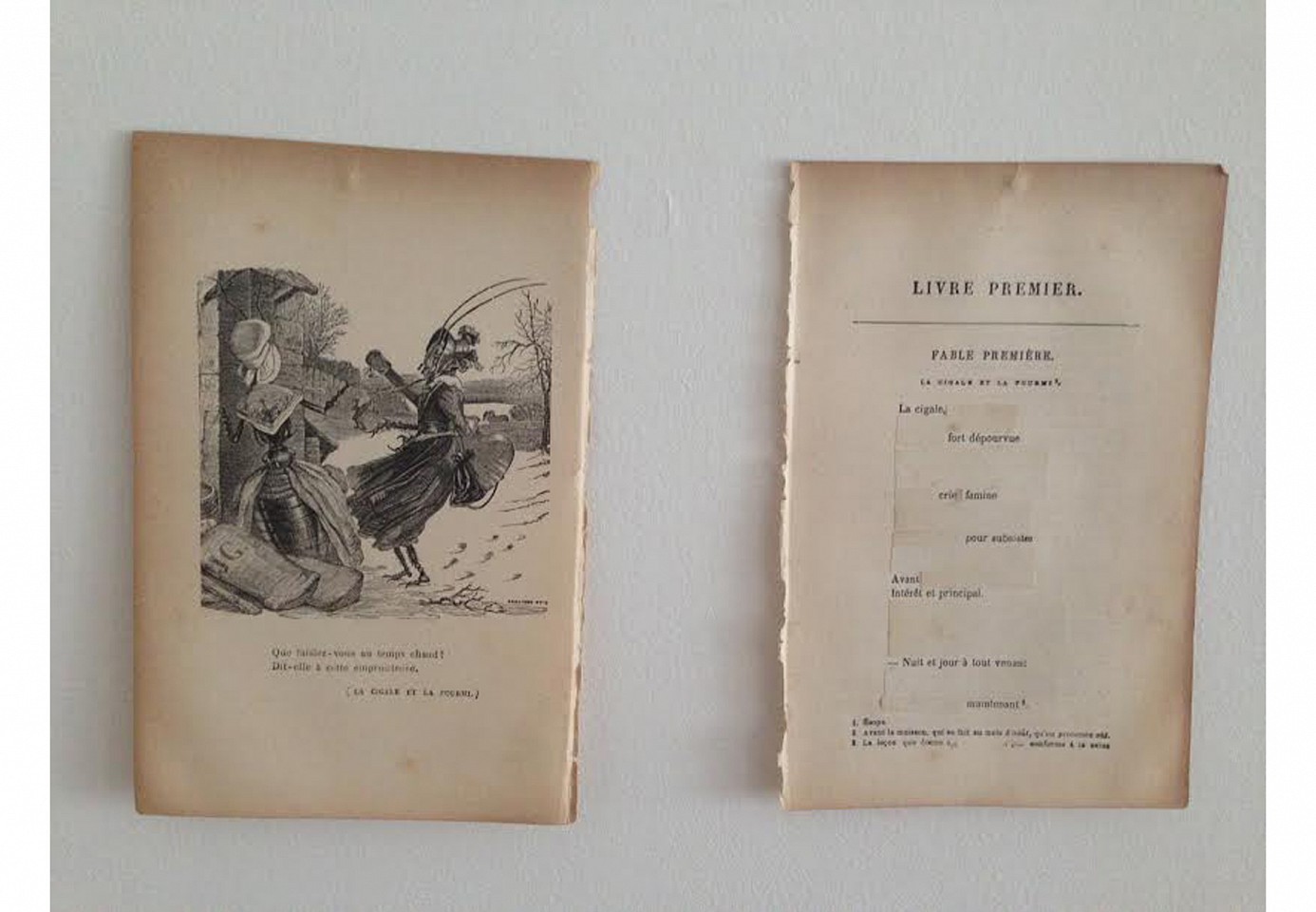

Aya Haidar

La Cigale et la Fourmi

Ink paper and collage

36.5 x 30 cm

From Babel Series

AYH0005

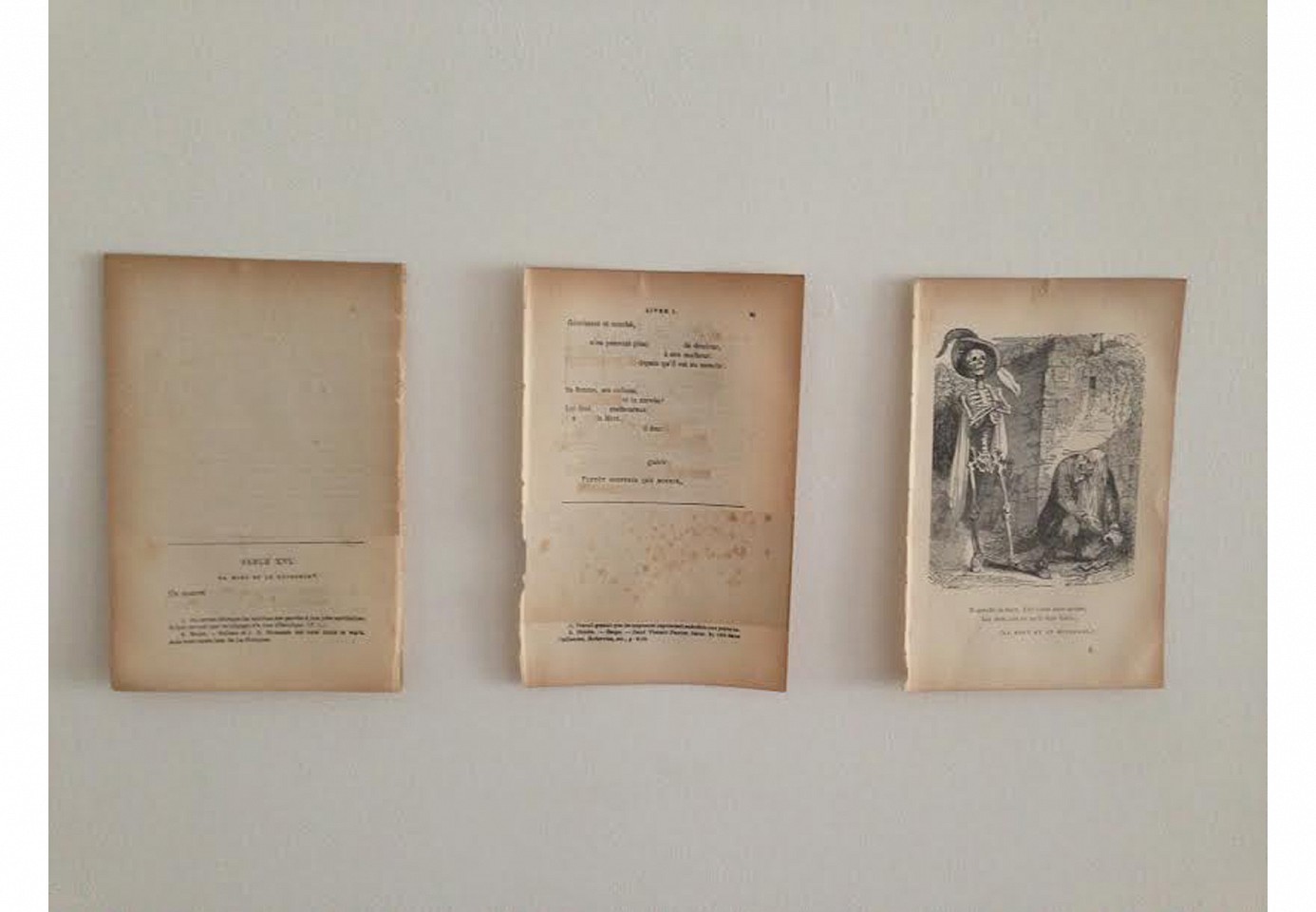

Aya Haidar

La mort et le Bucheron

Ink paper and collage

49 x 30 cm

From Babel Series

AYH0006

Aya Haidar

Boatloads, from the Soleless series, 2018

Embroidery on shoe soles

AYH0087

Aya Haidar

He walked from Turkey to Germany carrying his 3 kids on his back from the Soleless series, 2018

Embroidery on shoe soles

AYH0085

Aya Haidar

Patrol, from the Soleless series, 2018

Embroidery on shoe soles

AYH0086

Aya Haidar

Checkpoint from Soleless Series, 2010

Embroidered linen shoes

170 x 125 cm (66 7/8 x 49 3/16 in.)

AYH0009

Aya Haidar

What I Left Behind, 2018

Mixed media (cotton thread embroidered on patched fabric)

AYH0106

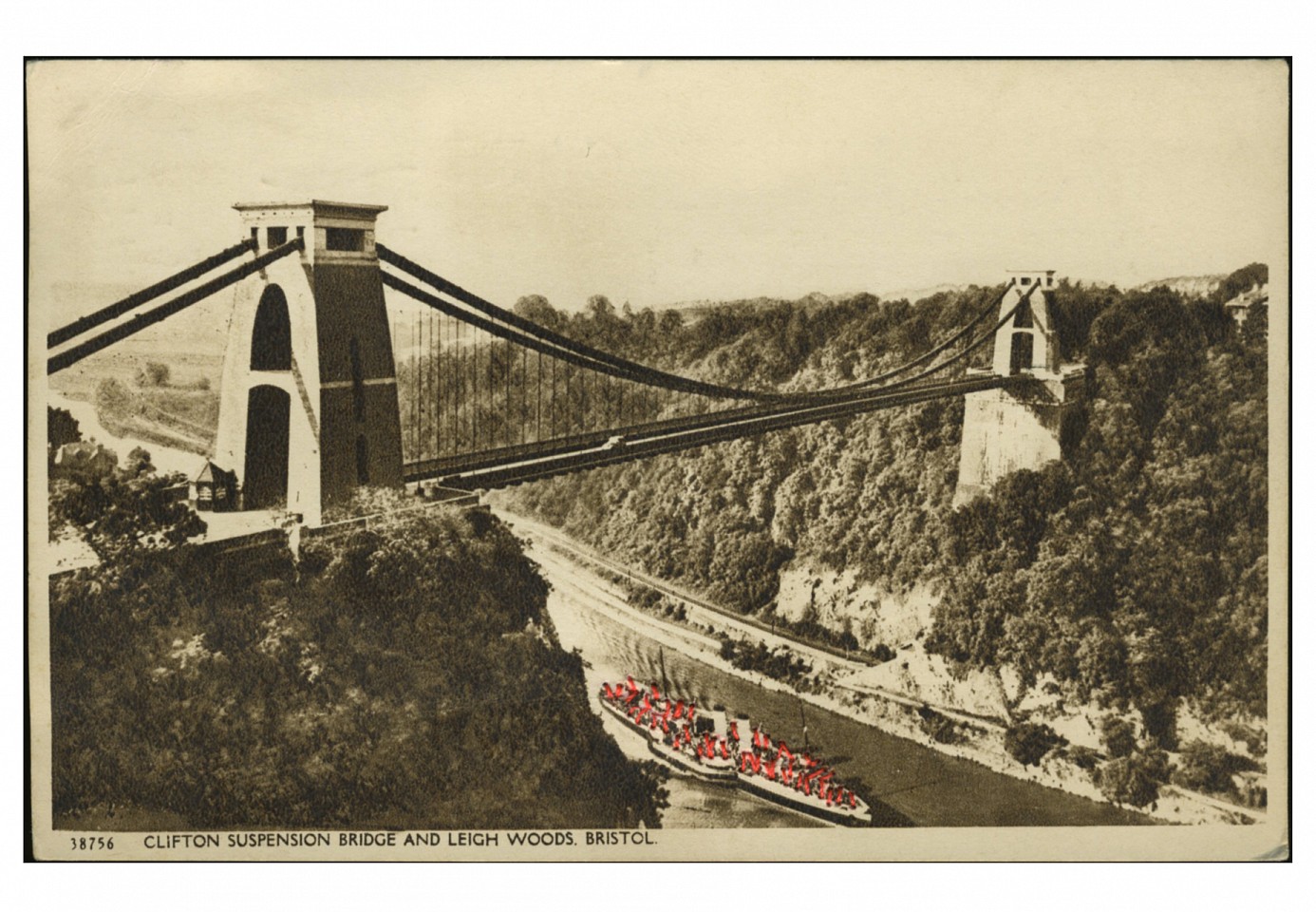

Aya Haidar

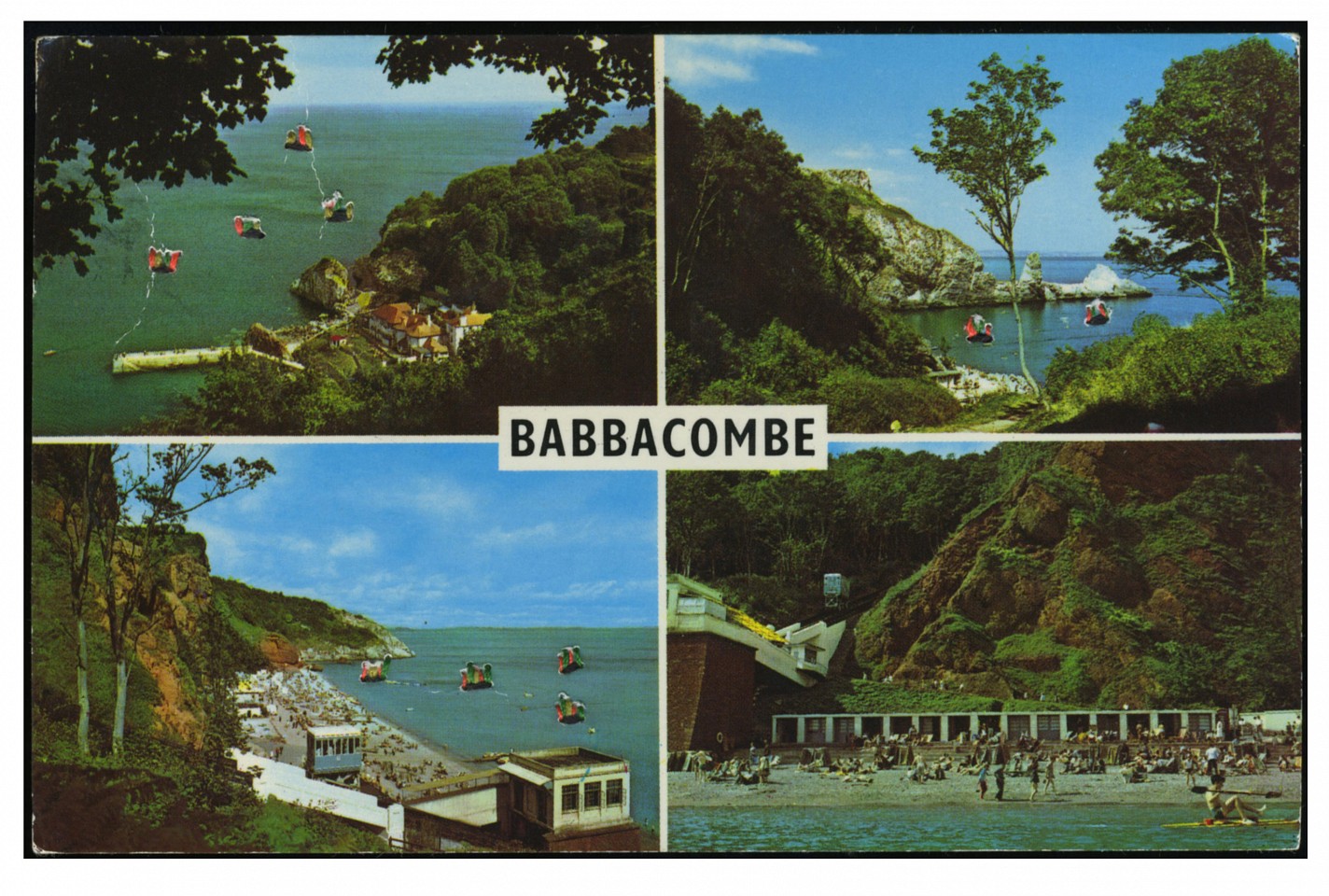

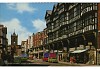

Postcard Collection 1: Untitled 1, 13, 17, 33, 43, 46, 52, 53, 57, 61, 85 and 86, 2016

Embroidery on postcard

From the Wish You Were Here series

AYH0071

Aya Haidar

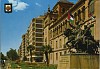

Postcard Collection 2: Untitled 2, 6, 18, 40, 44, 54, 34, 31, 8, 9, 11 and 12, 2016

Embroidery on postcard

From the Wish You Were Here series

AYH0072

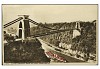

Aya Haidar

Postcard Collection 6: Untitled 19, 23, 36, 49, 55, 58, 64, 67, 75, 81, 83 and 87, 2016

Embroidery on postcard

From the Wish You Were Here series

AYH0075

Aya Haidar

Recollections II, 2011

Embroidery on printed linen

104 x 82 cm

From Seamstress Series

AYH0030

Aya Haidar

Recollections III, 2011

Embroidery on printed linen

87 x 63.5 cm

From Seamstress Series

AYH0036

Aya Haidar

Recollections VI, 2011

Embroidery on printed linen

56 x 42 cm

From Seamstress Series

AYH0033

Aya Haidar

Recollections XI, 2011

Embroidery on printed linen

43.5 x 23 cm

From Seamstress Series

AYH0031

Aya Haidar

Seamstress XX

Printed and embroidered onto Linen

52.5 x 68 cm

From Seamstress Series

AYH0000

Aya Haidar

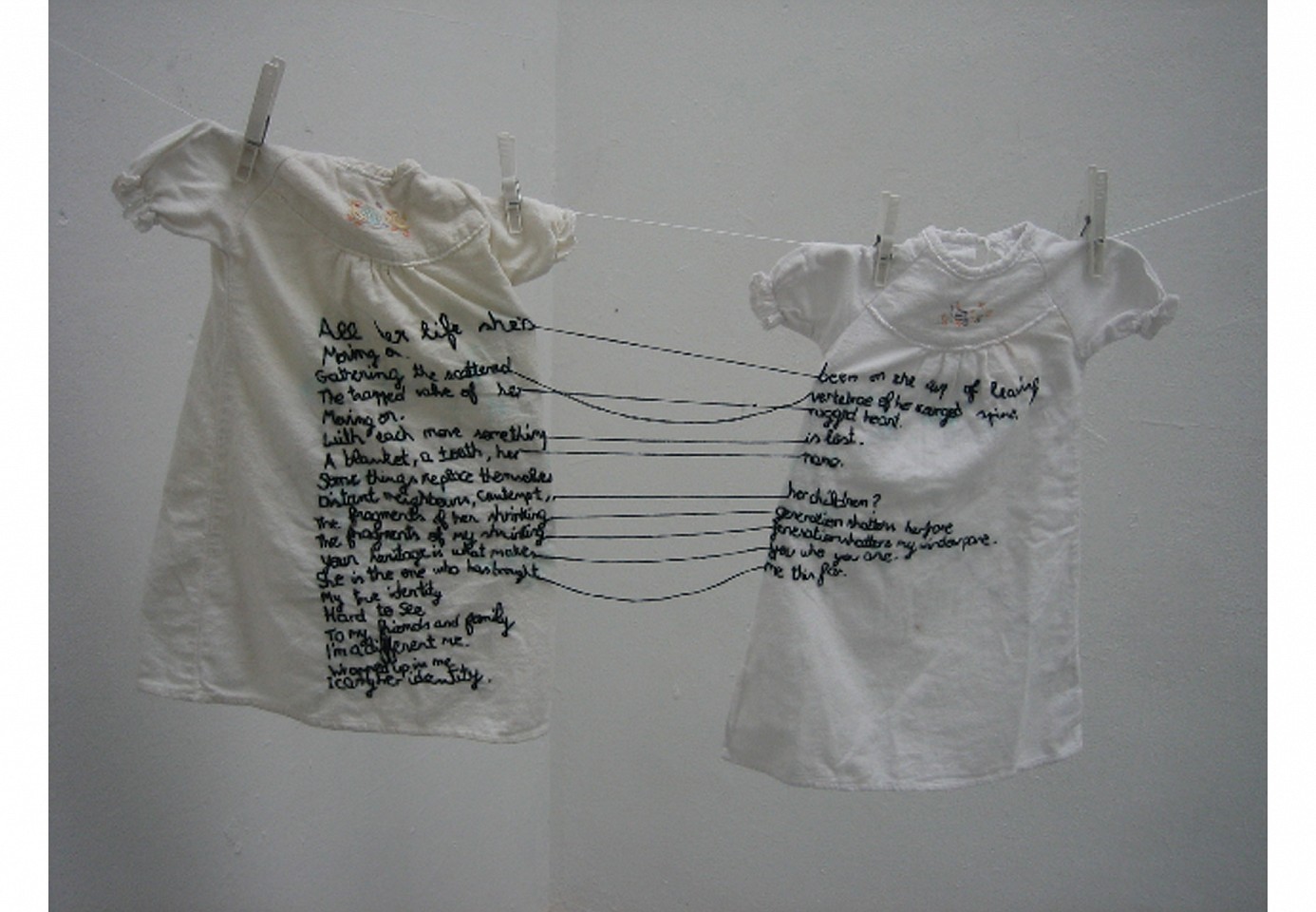

The Stitch is Lost Unless the Thread is Knotted, 2008

Shirts and thread

AYH0060

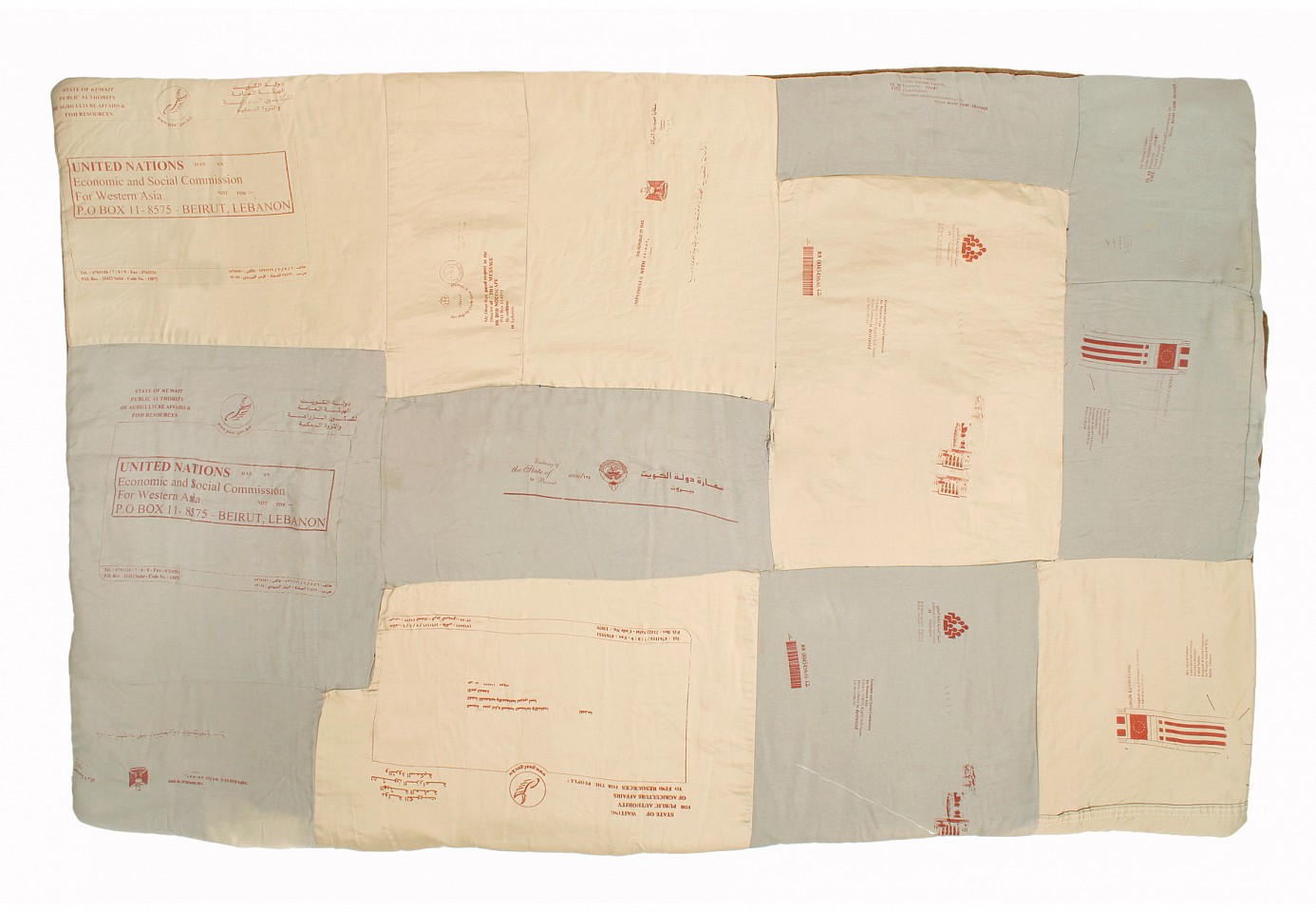

Aya Haidar

Return to Sender

Doctored text on original envelopes

100 x 120 cm

AYH0061

Aya Haidar

Coffee pot, Bread, Toothbrush, Bottle of water, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0096

Aya Haidar

Falafel, Coffee pot, Pistachio nuts, from of the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0092

Aya Haidar

Hijab, Medication, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0100

Aya Haidar

Period pad, sweets, Housekey, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0095

Aya Haidar

Swiss Army Knife, iPhone, Misbaha, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0098

Aya Haidar

Wedding photo, Phone Charger, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0094

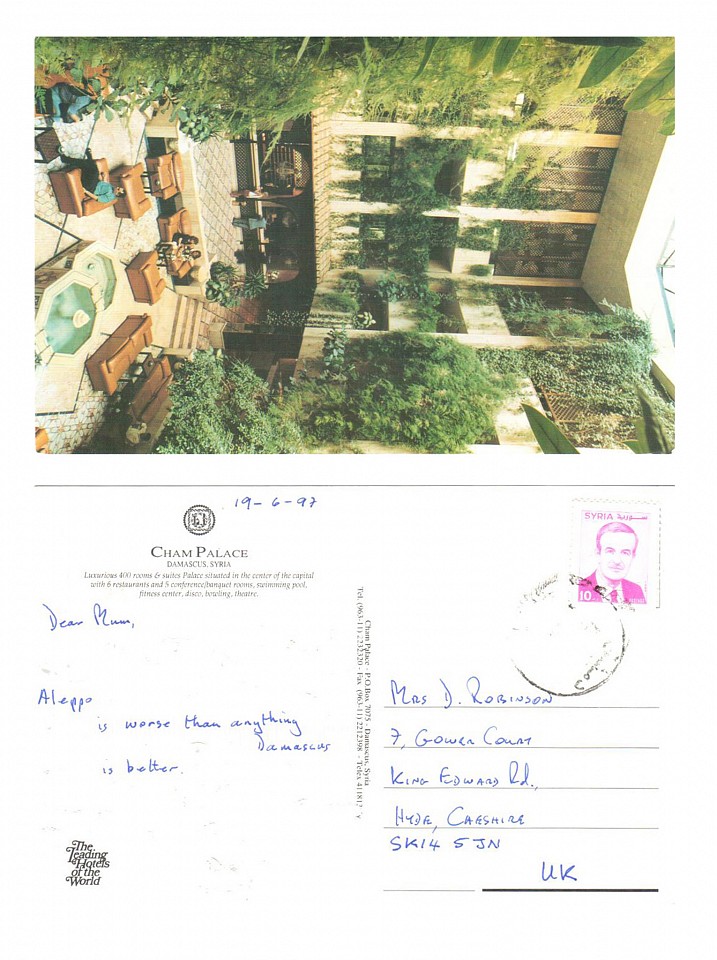

Aya Haidar

Aleppo is worse than anything. Damascus is better; from the Dear Mum series, 2017

Postcard

AYH0081

Aya Haidar

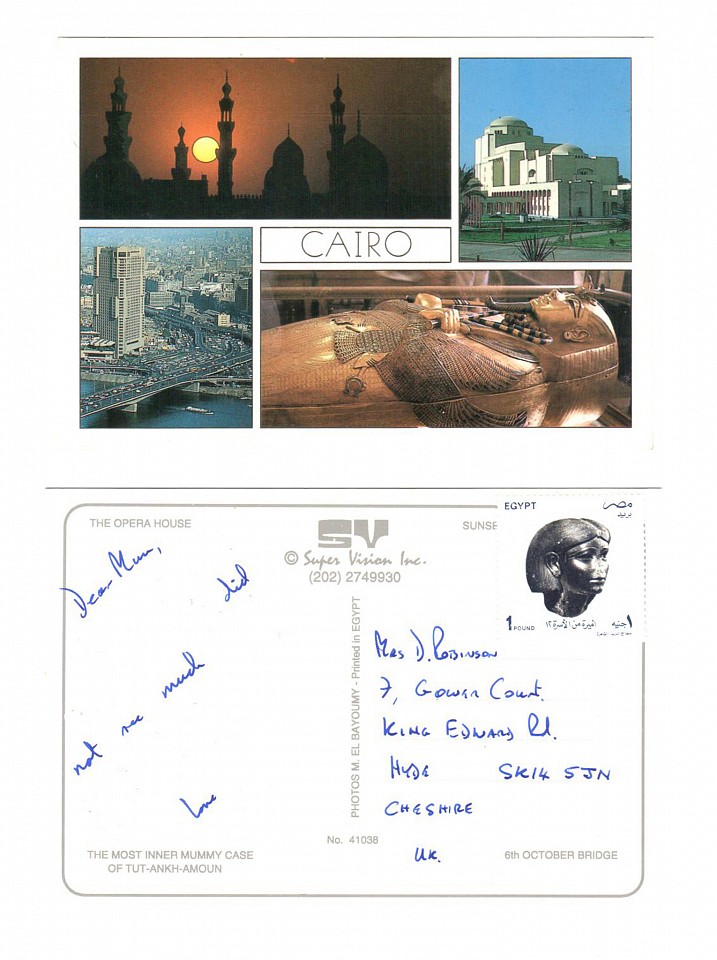

Did not see much love; from the Dear Mum series, 2017

Postcard

AYH0084

Aya Haidar

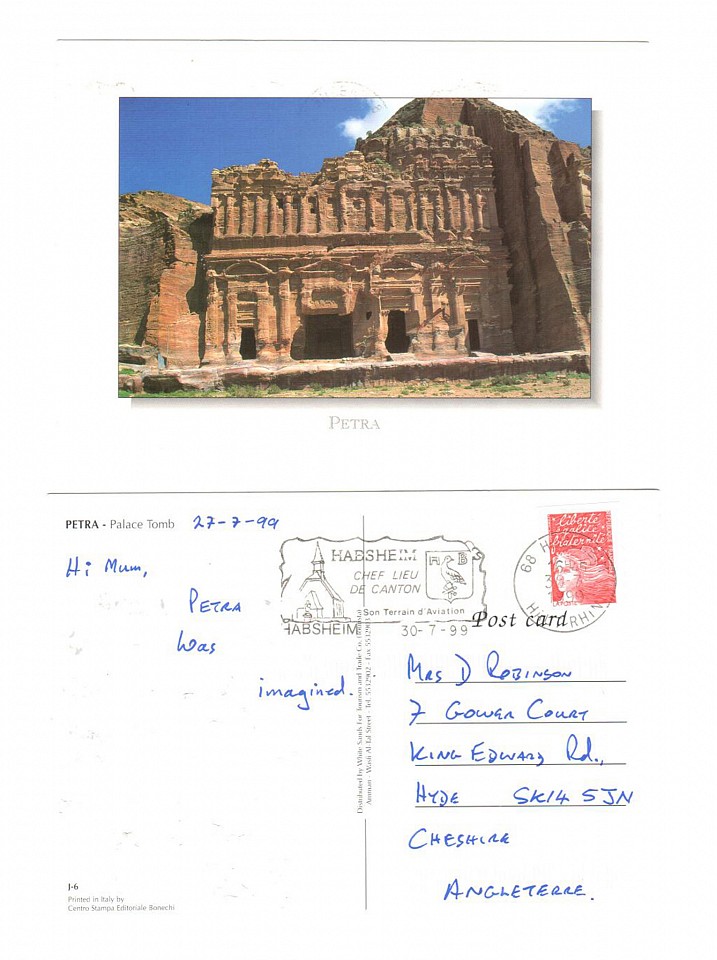

Petra was imagined; from the Dear Mum series, 2017

Postcard

AYH0083

Aya Haidar

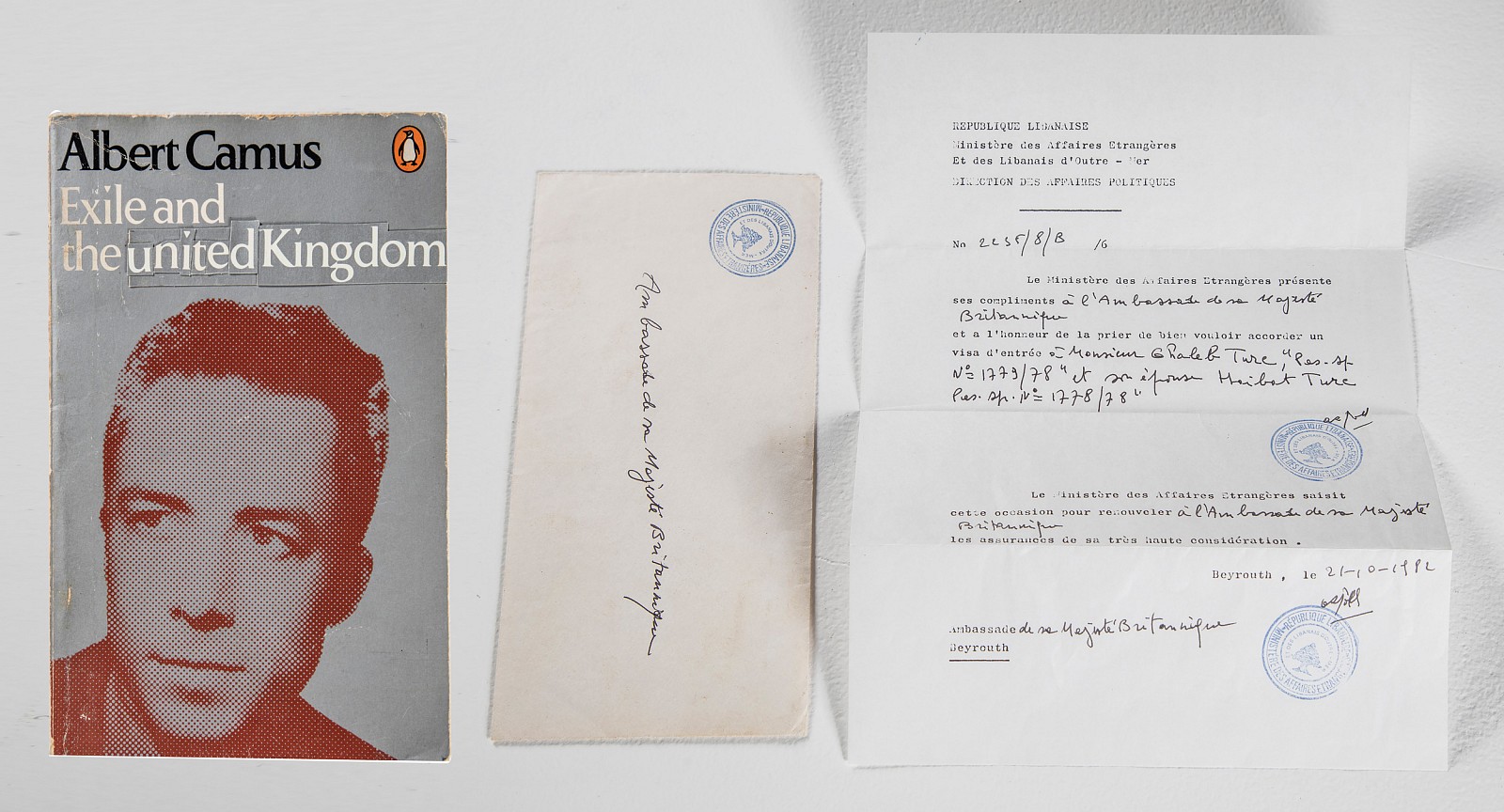

Exile and the United Kingdom, 2016

Book and Diplomatic Letter

AYH0064

Aya Haidar

Recollections XXII from Seamstress series

, 2011

Embroidery on printed linen

AYH0029

Countries (from left to right):

Oman – 1650 – Critica Sacra by Edward Leigh

Egypt – 1922 – The Beautiful and Damned by F.Scott Fitzgerald

Saudi Arabia – 1932 – Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Iraq – 1932 – The Journey to the East by Hermann Hesse

Lebanon – 1943 – Being and Nothingness by Jean Paul Sartres

Syria – 1946 - America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan

Jordan – 1946 – All Men are Mortal by Simone de Beauvoir

Israel – 1948 – The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene

Libya – 1951 – The Wisdom of Insecurity by Alan Wilson Watts

Tunisia – 1956 – The Last Battle by C.S.Lewis

Morocco – 1956 – French Leave by P.G Wodehouse

Kuwait – 1961 – Catch 22 by Joseph Heller

Algeria – 1962 – Capitalism and Freedom by Milton Friedman

UAE – 1971 – Tower of Glass by Robert Silverberg

Bahrain – 1971 – War and Remembrance by Herman Wouk

Qatar – 1971- That Was Then, This Is Now by S.E.Hinton

Iran – 1979 - The Never Ending Story by Michael Ende and Ralph Manheim

Yemen – 1990 – Homeland by R.A.Salvatore

The year a book is published is the year it becomes its own complete entity and is freed to the world. Similarly, the year of independence of a country is the year it, in principle, becomes its own entity and is liberated.

18 books are displayed, representing the 18 countries across the MENA region, whereby each book shares the same date of ‘liberation’ to its respective country’s year of freedom. Clear parallels are drawn between the books and countries based on that single year.

Presenting a linear historical chronicle of independence and liberation is significant. The choice of books highlights the reciprocity to their country’s respective affairs of state and adds a certain ironic, incisive and perhaps even humorous dimension. For instance, Morocco was liberated in 1956, the same year French Leave was published by P.G.Wodehouse. Similarly, Libya was liberated in 1951, the same year The Wisdom of Insecurity was published and Israel’s foundation in 1948 ironically shares the same year of publication as The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene.

In light of the current situation across the region, questions arise around the significance of dates of independence and whether countries were ever free in the first place. What is

significant, however, is the relationship between history and literature, politics and the written word as freedom of expression.

This body of work stands independently and in parallel to Year of Issue. Drawing on the 18 books published in the same years of independence as each respective country across the MENA region, and chosen specifically for their titles, these books have been turned face down and their covers photographed. Exploring language and the limitations of manipulating words, Aya have reworked each title to reveal a headline statement. Language is a powerful tool and recurrently manipulated to shape opinions and understandings. The artist is fascinated by the fluidity of text, and how the mere reshuffling of letters can create whole new contexts and open up new notions of understandings. This facilitation in the reworking of language as a form of communication is highlighted in the midst of stifled freedoms of expression

Taking every one of the 18 countries across the MENA region’s declaration of independence, the artist have decoded and recoded them into their own individual and respective digital QR code, which she have in turn embroidered onto panels of Egyptian cotton. Declarations of independence are proclamations that a given state and it’s nation are officially sovereign and ‘free’. The official dates are interesting when thinking about changes pre and post that mark, and whether any of them are indeed significant. What does it mean to truly be independent? Are any of these nations any more independent now than they were before such declarations? The fact that they were granted independence and not taken it themselves reflects masked power dynamics that have never truly dissolved.

The decoding and recoding of language is of particular interest. In today’s world, digital media has shaped not only our current state by democratizing and empowering from the bottom up, but it has also rewritten our language as means of communication. Each embroidered panel represents a declaration of independence respective to each country, translated into its own individual QR code. As each panel is hand embroidered, the lines, colour and textures are not as sharp and uniform as if it were digital, consequently making it impossible to successfully scan and read. Ironically, when brought back to the original means of communication, through the hand stitch, something gets lost in translation and new age media becomes redundant. By extension, the declarations become redundant, not only a physical level, but also on a conceptual one where their significance remains void in today’s world.

Artist Statement:

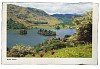

I discovered Jeddah’s old town, subsequently leading to my avid exploration of such a timeless site of true national heritage and pride. My time was spent photographing and documenting the architecture and surrounding areas, subsequently leading to the development of Al Balad (2012), a body of work merging modern-day printed digital photography on linen with the more traditional practice of hand stitched craft.

My representation of Jeddah’s old town looks into bridging the gap between the historical and the contemporary. The towering hand carved wooden facades that enrich the district are embellished and revived with the use of brightly coloured embroidery thread. The choice of colour of thread is deeply rooted in Saudi Bedouin culture and encapsulates Jeddah’s soul.

My investigation into the colour’s significance was a profound one, which left me in awe. Outsider notions of Saudi dress is limited to the black Abbaya for women, yet traditional Saudi culture and customs hold great importance in the value of colour and its symbolism to nature and surrounding environment. It is this celebration of the nature of identity- both historical through to the contemporary- that I wish to emphasise.

The deconstruction of the series- visually in terms of representation and symbolically in terms of colour and composition is what presents a multi-layered perception of such a multi-layered and resonant society.

Artist Statement:

I discovered Jeddah’s old town, subsequently leading to my avid exploration of such a timeless site of true national heritage and pride. My time was spent photographing and documenting the architecture and surrounding areas, subsequently leading to the development of Al Balad (2012), a body of work merging modern-day printed digital photography on linen with the more traditional practice of hand stitched craft.

My representation of Jeddah’s old town looks into bridging the gap between the historical and the contemporary. The towering hand carved wooden facades that enrich the district are embellished and revived with the use of brightly coloured embroidery thread. The choice of colour of thread is deeply rooted in Saudi Bedouin culture and encapsulates Jeddah’s soul.

My investigation into the colour’s significance was a profound one, which left me in awe. Outsider notions of Saudi dress is limited to the black Abbaya for women, yet traditional Saudi culture and customs hold great importance in the value of colour and its symbolism to nature and surrounding environment. It is this celebration of the nature of identity- both historical through to the contemporary- that I wish to emphasise.

The deconstruction of the series- visually in terms of representation and symbolically in terms of colour and composition is what presents a multi-layered perception of such a multi-layered and resonant society.

The Babel Series' concept draws on the biblical story evoking the confusion of tongues and variations of the human language. The disorder and misunderstanding of communication led to the downfall of humanity and is a trend that is ever perpetuated today. Seminal texts are explored within this series, of which;

Jean de la Fontaine's 17th Century French literary classic Fables de la Fontaine presents lively stories in verse, grazing and sometimes transgressing the bounds of contemporary moral standards. By looking at language as a multilayered and multi faceted channel of communication, the deconstruction and reconstruction of the text allows for alternative narratives to break through.

An alternative overlays the former structure of the original text, unveiling a further underlying poetic prose.

The Babel Series' concept draws on the biblical story evoking the confusion of tongues and variations of the human language. The disorder and misunderstanding of communication led to the downfall of humanity and is a trend that is ever perpetuated today. Seminal texts are explored within this series, of which;

Jean de la Fontaine's 17th Century French literary classic Fables de la Fontaine presents lively stories in verse, grazing and sometimes transgressing the bounds of contemporary moral standards. By looking at language as a multilayered and multi faceted channel of communication, the deconstruction and reconstruction of the text allows for alternative narratives to break through.

An alternative overlays the former structure of the original text, unveiling a further underlying poetic prose.

This current body of work from the Soleless series has been produced in response to a 3 month artist residency program, working directly in reintegrating newly arrived Syrian refugee communities into the UK.

From this experience, first-hand accounts and interpersonal exchanges over the perilous passages ventured, stories of separation, loss and every day realities are intimately embroidered on the underside of worn shoes.

This current body of work from the Soleless series has been produced in response to a 3 month artist residency program, working directly in reintegrating newly arrived Syrian refugee communities into the UK.

From this experience, first-hand accounts and interpersonal exchanges over the perilous passages ventured, stories of separation, loss and every day realities are intimately embroidered on the underside of worn shoes.

This current body of work from the Soleless series has been produced in response to a 3 month artist residency program, working directly in reintegrating newly arrived Syrian refugee communities into the UK.

From this experience, first-hand accounts and interpersonal exchanges over the perilous passages ventured, stories of separation, loss and every day realities are intimately embroidered on the underside of worn shoes.

This patched quilt frames 6 panels, each carefully embroidered around the Narratives shared by refugees about the things they most regretfully left behind in their native Syria. A generational and geographical cross section, looking back at the homeland they left with the adored individuals and valued things they could not save with them. A young Layal innocently describing how she left her toys under her bed to keep them safe until she returns; Naim who recently graduated with a biochemistry degree, leaving his certificate behind; Rafic the family dog who couldn’t be taken; to leaving one’s elderly parents because they refused to leave their homeland; Huda’s family photo albums spanning generations; to Mohannad’s ID papers making him feel like he has lost his identity with nowhere to go and no way to prove where he has come from. These inter personal revelations are carefully hand embroidered onto collected items of clothing where the fabric itself bears the weight of the journey as much as the story itself. The patched fabric used to create the borders around each panel has been locally sourced in the UK where this group of refugees has now been relocated. This fabric is used to upholster and drape the furnishings of their new homes.

Wish You Were Here is a collection of 100 used postcards from across Europe, which are doctored using hand embroidery. Each subtle intervention presents a social commentary reflecting the current landscape across the region.

Postcards serve to highlight the beauty of a city or landscape yet never seem to present the whole reality. The composition of the postcard images are so well framed and immaculate that such embroidered interventions serve to broaden the lens towards a more realistic insight of the current socio-political context. Beautiful shots of the Mediterranean coast are carefully altered to include rubber dinghies carrying refugees towards shore or gorgeous piazzas play host to a multitude of tented settlements or protests.

The embroidered additions take such stagnant images and pull them into a current discourse of border politics amidst an ever escalating refugee crisis. The title, Wish You Were Here, has a direct relational association to postcards and highlights the link that postcards have to 'home' or a sense of 'longing for home'. The irony of the pun intended, that someone would 'wish they were there' when considering the stark reality of what is being represented. Each embroidered postcard is unique and presents its own narrative. They are presented as an installation, onto rotating postcard stands, for the audience to navigate around and intimately view and reflect on the reality that each postcard presents.

Artist Statement:

In the centre of Martyrs’ Square in downtown Beirut, Lebanon, is a statue depicting a woman, one arm bearing a torch aloft, the other around the shoulders of a young boy. The statue is riddled with bullet holes from the wars, uprisings and political unrest that have pockmarked the 69 years of Lebanese independence. A photograph of the landmark crops in on the two figures whose bullet wounds have been carefully, tenderly stitched over in a variety of multi-coloured bandages. Another view shows the woman completely wrapped, Christo-like, in red thread. These interventions by Aya Haidar, on photographs printed on linen (both from the body of work Recollections from the series ‘Seamstress’) illustrate the artist’s method of both highlighting and concealing the marginalia normally overlooked in both the images and narratives of the country’s troubled past.

Though of Lebanese heritage, Haidar has never been a permanent Lebanese resident. Using stories told to her when knitting with her grandmother and accountsof friends and people the artist has met in Lebanon, Haidar reconstructs her own versions of historical events through re-imaginings that float between the historically symbolic and the personally significant.

Artist Statement:

In the centre of Martyrs’ Square in downtown Beirut, Lebanon, is a statue depicting a woman, one arm bearing a torch aloft, the other around the shoulders of a young boy. The statue is riddled with bullet holes from the wars, uprisings and political unrest that have pockmarked the 69 years of Lebanese independence. A photograph of the landmark crops in on the two figures whose bullet wounds have been carefully, tenderly stitched over in a variety of multi-coloured bandages. Another view shows the woman completely wrapped, Christo-like, in red thread. These interventions by Aya Haidar, on photographs printed on linen (both from the body of work Recollections from the series ‘Seamstress’) illustrate the artist’s method of both highlighting and concealing the marginalia normally overlooked in both the images and narratives of the country’s troubled past.

Though of Lebanese heritage, Haidar has never been a permanent Lebanese resident. Using stories told to her when knitting with her grandmother and accountsof friends and people the artist has met in Lebanon, Haidar reconstructs her own versions of historical events through re-imaginings that float between the historically symbolic and the personally significant.

Artist Statement:

In the centre of Martyrs’ Square in downtown Beirut, Lebanon, is a statue depicting a woman, one arm bearing a torch aloft, the other around the shoulders of a young boy. The statue is riddled with bullet holes from the wars, uprisings and political unrest that have pockmarked the 69 years of Lebanese independence. A photograph of the landmark crops in on the two figures whose bullet wounds have been carefully, tenderly stitched over in a variety of multi-coloured bandages. Another view shows the woman completely wrapped, Christo-like, in red thread. These interventions by Aya Haidar, on photographs printed on linen (both from the body of work Recollections from the series ‘Seamstress’) illustrate the artist’s method of both highlighting and concealing the marginalia normally overlooked in both the images and narratives of the country’s troubled past.

Though of Lebanese heritage, Haidar has never been a permanent Lebanese resident. Using stories told to her when knitting with her grandmother and accountsof friends and people the artist has met in Lebanon, Haidar reconstructs her own versions of historical events through re-imaginings that float between the historically symbolic and the personally significant.

Artist Statement:

In the centre of Martyrs’ Square in downtown Beirut, Lebanon, is a statue depicting a woman, one arm bearing a torch aloft, the other around the shoulders of a young boy. The statue is riddled with bullet holes from the wars, uprisings and political unrest that have pockmarked the 69 years of Lebanese independence. A photograph of the landmark crops in on the two figures whose bullet wounds have been carefully, tenderly stitched over in a variety of multi-coloured bandages. Another view shows the woman completely wrapped, Christo-like, in red thread. These interventions by Aya Haidar, on photographs printed on linen (both from the body of work Recollections from the series ‘Seamstress’) illustrate the artist’s method of both highlighting and concealing the marginalia normally overlooked in both the images and narratives of the country’s troubled past.

Though of Lebanese heritage, Haidar has never been a permanent Lebanese resident. Using stories told to her when knitting with her grandmother and accountsof friends and people the artist has met in Lebanon, Haidar reconstructs her own versions of historical events through re-imaginings that float between the historically symbolic and the personally significant.

In the centre of Martyrs’ Square in downtown Beirut, Lebanon, is a statue depicting a woman, one arm bearing a torch aloft, the other around the shoulders of a young boy. The statue is riddled with bullet holes from the wars, uprisings and political unrest that have pockmarked the 69 years of Lebanese independence. A photograph of the landmark crops in on the two figures whose bullet wounds have been carefully, tenderly stitched over in a variety of multi-coloured bandages. Another view shows the woman completely wrapped, Christo-like, in red thread. These interventions by Aya Haidar, on photographs printed on linen (both from the body of work Recollections from the series ‘Seamstress’) illustrate the artist’s method of both highlighting and concealing the marginalia normally overlooked in both the images and narratives of the country’s troubled past.

Though of Lebanese heritage, Haidar has never been a permanent Lebanese resident. Using stories told to her when knitting with her grandmother and accounts of friends and people the artist has met in Lebanon, Haidar reconstructs her own versions of historical events through re-imaginings that float between the historically symbolic and the personally significant.

Artist Statement:

A series of envelopes circulated around the Middle East were collected in their common place at the United Nations headquarters in Beirut. The text, seals and logos on the face of the envelopes have subsequently been subtly doctored to reveal current truths and raise critical questions with regard to power dynamics and reflections across the region. The deconstruction of text generates a reworking of language, controlled and directed by the artist. The envelopes themselves, circulated by the UN play a huge part in the democratization of expression. Originally used to transmit urgent and confidential information, they have now become channels and platforms for the diffusion of information.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.