Ahmed Mater

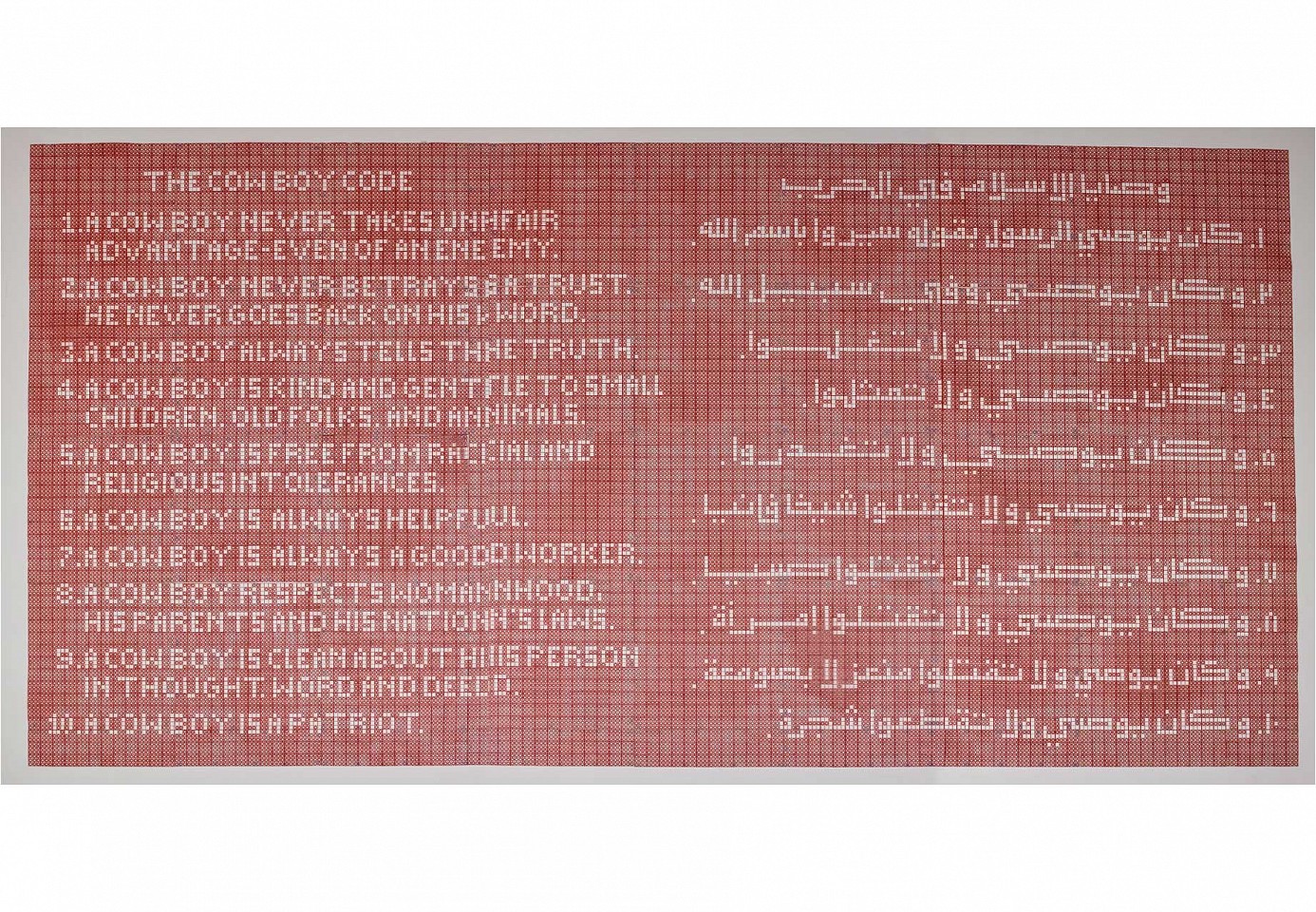

Cowboy Code II, 2012

Plastic Gun Powder Caps

400 x 800 cm (157 7/16 x 314 15/16 in.)

AHM0231

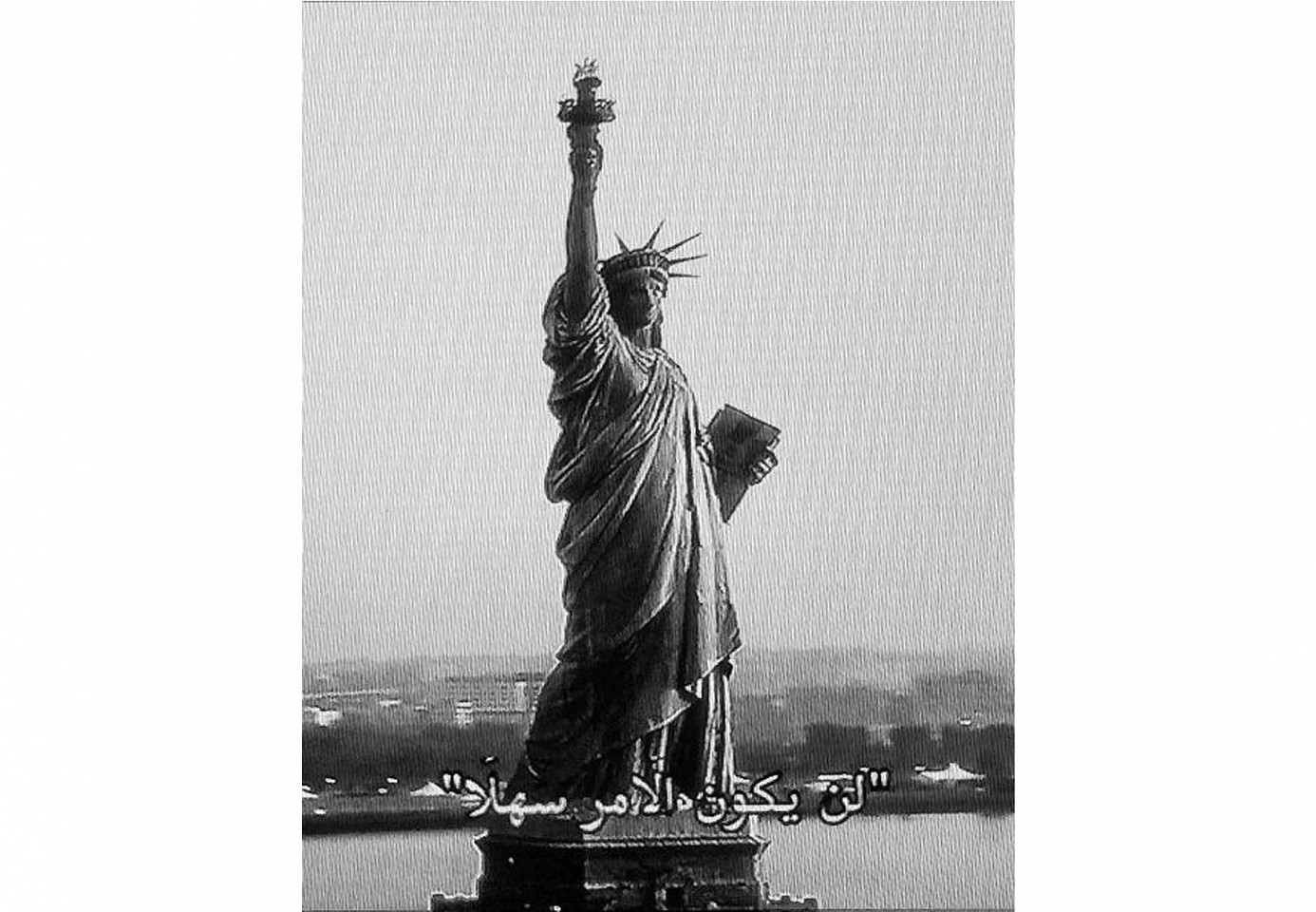

Ayman Yossri Daydban

It Will Not Be An Easy Matter, 2012

Photographic Print on Archival Paper

62 x 110 cm (24 3/8 x 43 1/4 in.)

From Subtitle series, Edition of 3

AYD0321

Ahmed Mater’s The Cowboy Code (2012), is a large-scale wall based installation of ten commandments, listed in Arabic and English using plastic toy gun caps. The commandments or codes are an appropriation of a song first performed by Gene Autry in the 40s.

The timeless character of the vagabonding cowboy is a persona once present throughout the pictures houses of Mater’s youth – a playful and frivolous character on the outside but with an almost inviolable moral core. For Mater, the cowboy is the nomad of the Western sands, much like the Bedouin is the nomad of the Eastern sands. Through this work, the artist is seeking out what unites ‘us’ (East and West) rather than what sets us apart. He makes comparisons between the language of two codes of ethics, one from the American West and one from the Islamic code referring to statements or actions of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), known as the Hadith.

“When we were children, we often played with toy guns, and would buy the little red caps from the local shop. They were called ‘Western Gun Caps’. You could get them everywhere in Saudi Arabia. We imitated the cowboys we saw on television. Their language, their clothes, their values.”

The Cowboy Code

1 A cowboy never takes unfair advantage – even of an enemy.

2 A cowboy never betrays a trust. He never goes back on his word.

3 A cowboy always tells the truth.

4 A cowboy is kind and gentle to small children, old folks, and animals.

5 A cowboy is free from racial and religious intolerances.

6 A cowboy is always helpful when someone is in trouble.

7 A cowboy is always a good worker.

8 A cowboy respects womanhood, his parents and his nation’s laws.

9 A cowboy is clean about his person in thought, word, and deed.

10 A cowboy is a Patriot.

The Hadith (Translation)

1 The Prophet cautioned to always march in the name of God.

2 He cautioned to always march in the path of God.

3 He cautioned never to be extreme or fanatic.

4 He cautioned never to desecrate the bodies of your fallen enemy.

5 He cautioned never to take unfair advantage of your enemy.

6 He cautioned never to harm the elderly.

7 He cautioned never to harm children.

8 He cautioned never to harm women.

9 He cautioned never to harm holy men.

10 He cautioned never to cut down trees.

“Over the course of ten years, our lives changed completely. It is a drastic change that I experience every day. The Cowboy Code is something I have thought about for years. When I was a child, the cowboy was always a symbol of freedom and adventure, an ideology that came from the West and assimilated itself into my culture. Like many of my generation, I have taken a lot from the West – the food we eat, clothes we wear, even our language and so I wanted to present this code as a way of reclaiming these qualities as opposed to purely commodity driven influences. I want to move these compatible beliefs away from the politics, from the media and give them back to the people.”

-Ahmed Mater

The basic function for the Arabic language associated with a foreign language film shown on the screen... is translation. It works in the context of the film as a narration of the story and an explanation of the action that accompanies it ... and thus the meaning of the picture precedes that of the language and specifies it.

The language, when deducted from its cruel context and re-exported with the image of the new still captured photo, changes its function from confirming the meaning to producing it, by transforming itself to a unique source of new mental images with no past or function.

The Armory, NY

Booth 631 MENA, Focus

New York City, USA

Complex systems of communication are deeply entrenched in human culture. Language, in addition to its strictly communicative uses, has many social and cultural behaviours – governing and regulating group identity, social stratification, as well as social grooming, entertainment, religious and political control. There are in this way, inherent possibilities in the relationship between language and art, particularly when considering art’s material qualities – visual, aural and beyond. The philosophy of language and its societal role has been argued since Gorgias and Plato in Ancient Greece – the question of whether its fundamental purpose is to represent experience, emotion or logical thought is a continued source of inquiry. Language – as it appears in contemporary art – questions innate properties of productivity, recursivity, and displacement.

Taking visual art's ongoing engagement – and entanglement – with language as its departure, the proposed presentation acknowledges language’s labyrinthine qualities, its endless possible permutations and considers distinctive manifestations of language in film and popular media. Within each work, language is denied its interpretive or explicatory function, narratives are outlined then refuted, nostalgic associations are savored and then curbed. The works embrace language's more permeable state: its elasticity, its penchant for questions, misinterpretation, subtexts and double meanings. Exploring language's ability to prompt empathy, the works are emotive and occasionally melancholic, collectively they embrace questions of politics, identity, idealism, and alienation. Prevailing throughout is a nagging sense of inevitability that reflects upon - and perhaps even amplifies - the uncertain future of Saudi’s and the region’s social landscape.

The artists Ayman Yossri Daydban, Mahdi Al Jeraibi, Bakr Shaykhoon and Ahmed Mater use the opportunity language affords to move freely between disciplines – exploring film, sculpture, artefact and found matter – experimenting with language, they liberate it from the page and from its systematic and descriptive duties and transport it to more mutable territories. The works selected for Armory 2015 more specifically take ‘language as artifact’ as a shared premise and approach. The pieces look towards underlying messaging, communicating to a present and future, they rely on the idiosyncratic use of language in recent history and pop culture. They address language as a remnant, residual evidence of experience and of defining cultural threads. For the works selected, the letter, the word and the phrase are seen and experienced as well as read. Language that was once common-place and used across a variety of popular media in Saudi Arabia in the 70s and 80s, when combined with symbolic objects, becomes a trigger to a retrospective understanding of collective experiences and the parameters of social conditioning within Saudi society. Through these works, each artist explores a haunting, a capturing of defining moments in their own more subjective recollections.