Nasser Al Salem

Kull VI, 2015

Print on layered Acrylic

110 x 110 x 15 cm (43 1/4 x 43 1/4 x 5 7/8 in.)

Edition of 5

NAS0248

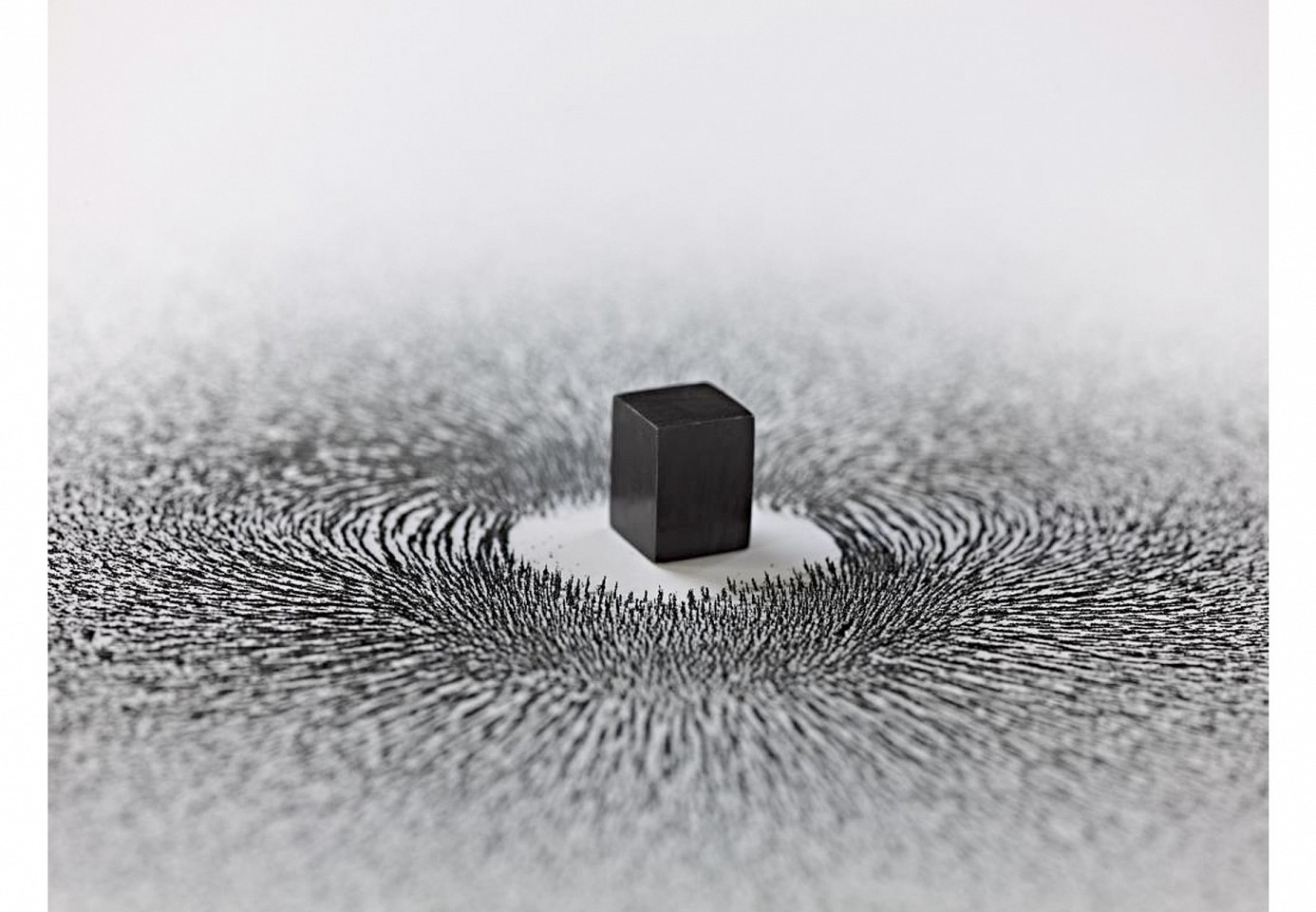

Ahmed Mater

Magnetism Installation, 2009

Magnet and iron shavings

200 x 90 x 90 cm (78 11/16 x 35 3/8 x 35 3/8 in.)

From Magnetism series, Edition of 5

AHM0173

The direct translation of Kul is ‘all’ or ‘everything’. However, the connotation of the word Kul in the Arabic language is so much more complex in its all-encompassing meaning and implication of infinity. This meaning is compounded by the artist’s technique of calligraphically depicting the word Kul repeatedly, so that it resembles an endless ripple effect.

The impression of never-ending repetition is not merely a reflection of God’s abundance on Earth, but an indication to look both further, and deeper, to penetrate the mere appearance and surface of things, to discover the hidden messages that all aesthetic creation hold.

Once, we thought the atom was the smallest particle, before we discovered that it was made of numerous smaller ones, as we once thought that the extent of our universe was the Milky Way Galaxy, before we discovered that there were hundreds of billions more galaxies out there. As God’s creation is infinite, and while we can say or write the word ‘infinite’ easily, it is impossible to imagine as it extends far beyond the human brain’s capacity for comprehension. Therefore, if one thinks of Kul too deeply or for too long, they might realize that it doesn’t exist; there is no ‘all’ or ‘everything’.

(Tim Makintosh-Smith) The idea is simple and, like its central element, forcefully attractive. Ahmed Mater gives a twist to a magnet and sets in motion tens of thousands of particles of iron, a multitude of tiny satellites that forms a single swirling nimbus. Even if we have not taken part in it, we have all seen images of the Hajj, the great annual pilgrimage of Muslims to Mecca. Ahmed's black cuboid magnet is a small simulacrum of the black-draped Ka'bah, the 'Cube', that central element of the Meccan rites. His circumambulating whirl of metallic filings mirrors in miniature the concentric tawaf of the pilgrims, their sevenfold circling of the Ka'bah.

Al-Bayt al-'Atiq, the Ancient House, to give the Ka'bah another of its names, is ancient – indeed archetypal - in more than one way. The cube is the primary building-block, and the most basic form of a built structure. And the Cube, the Ka'bah, is also Bayt Allah, the House of the One God: it was built by Abraham, the first monotheist, or in some accounts by the first man, Adam. Its site may be more ancient still: 'According to some traditions,' the thirteenth-century geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi wrote, 'the first thing God created on earth was the site of the Ka'bah. He then spread out the earth from beneath this place. Thus it is the navel of the earth and the mid-point of this lower world and the mother of villages.' The circumambulation of the pilgrims, Yaqut goes on to explain on the authority of earlier scholars, is the earthly equivalent of the angels' circling the heavenly throne of God, seeking His pleasure after they had incurred His wrath. To this day, and beyond, the Ka'bah is a focal point of atonement and expiation; in the Qur'anic phrase, 'a place of resort for mankind and a place of safety'.

Ahmed Mater's Magnetism, however, gives us more than simple simulacra of that Ancient House of God. His counterpoint of square and circle, whorl and cube, of black and white, light and dark, places the primal elements of form and tone in dynamic equipoise. And there is another dynamic and harmonious opposition implicit in both magnetism and pilgrimage – that of attraction and repulsion. The Ka'bah is magnet and centrifuge: going away, going back home, is the last rite of pilgrimage. There is, too, a lexical parallel: the Arabic word for 'to attract', jadhaba, can also on occasion signify its opposite, 'to repel'. ('In Arabic, everything means itself, its opposite, and a camel,' somebody once said; not to be taken literally, of course, although the number of self-contradictory entries in the dictionary is surprising.) And yet all this inbuilt contrariness is not so strange: 'Without contraries,' as William Blake explained, 'there is no progression. Attraction and repulsion . . . are necessary to human existence.'

But Ahmed Mater's magnets and that larger, Meccan lodestone of pilgrimage can also draw us to things beyond the scale of human existence, and in two directions at once – out to the macrocosmic, and in to the subatomic. In the swirl of Ahmed's magnetized particles and the orbitings of the Mecca pilgrims are intimations of the whirl of planets, the gyre of galaxies. Hayy ibn Yaqzan, fictional brainchild of the twelfth-century Andalusian philosopher Ibn Tufayl (and perhaps both a spiritual precursor of the Mevlevi 'whirling dervishes' and a literary ancestor of Robinson Crusoe), made this latent link between terrestrial and celestial tawaf explicit. Looking skyward from the island on which he had been marooned as an infant and had grown to the age of reason, he observed the heavenly bodies - and then began to imitate their orbital motions, 'sometimes walking or running a great many times round about his House or some Stone,' in Simon Ockley's translation of 1708, 'at other times turning himself round so often that he was dizzy.' (In a footnote Ockley, a Cambridgeshire clergyman, thought all this 'extreamly ridiculous'; his Arabic was clearly better than his metaphysics.) And, to pursue the other, inward path, into the microcosm, might not a Hayy ibn Yaqzan born into the age of particle physics find himself equally inspired by the motion of electrons? Magnetism, gravity, attraction-repulsion are necessary not just to human existence, but to the very being of the cosmos; they are what make worlds both large and small go round. Some commentators, like the literary Elizabethan Sir John Davies, have given these forces another name, more poetic but no less apt:

Kind nature first doth cause all things to love; Love makes them dance, and in just order move.

Love is what sets in motion the Mevlevi, whirling in his perfect white corolla of skirts, and the circling planet, and the circumambulating pilgrim, and the subatomic tawaf of the atom that makes it all possible.

Perhaps then this is the conclusion to which Ahmed Mater's Magnetism draws us: that there is a dynamic unity running through creation; that in all things the Creator – 'the ordainer of order and mysticall Mathematicks,' as Dr Thomas Browne (like Dr Ahmed Mater, a creative physician-metaphysician) called Him – has set in balance the forces of pull and push and light and dark, has circled the square, and given exquisite form to inchoate matter. That, at any rate, is my conclusion, and it is why Ahmed's works work for me; both these and the mystical anatomies of his Illuminations. Like good poetry, they speak on a modest and graspable scale of things that are too big or too small or too mysterious to comprehend with the naked mind.

And what of Ahmed Mater himself, giving a twist to the magnet: is there a touch of the demiurge in him - of the creator with a small c? Yes; and one cannot be an artist without that touch.

Look again, and you may also observe in him a touch of the majdhub – literally, 'one who has been attracted'. Here I mean it not in the debased sense it has taken on in many Arabic dialects, that of someone who is a little mad; but in the sense in which it is used in Islamic mystical texts, that of someone who has lost his personal consciousness in the knowledge of the Oneness of God.

Another way to translate it might be, 'magnetized by the divine'.

"It implies an idea of movement, and symbolizes the cycle of time, the perpetual motion of everything that moves, the planets' journey around the sun (the circle of the zodiac), the great rhythm of the universe. The circle is also zero in our system of numbering, and symbolizes potential, or the embryo. It has a magical value as a protective agent [...] and indicates the end of the process of individuation, of striving towards a psychic wholeness and self-realization" (Julien, 71).

The circle has been known since before the beginning of recorded history. From micro to macro contexts the circle plays myriad roles, from biological structures to planetary movements. Beyond the natural circles that early man would have observed, such as the moon or sun, the circle is the basis for the wheel, which, with related inventions such as gears, makes much of modern machinery possible. In mathematics, the study of the circle has helped inspire the development of geometry, astronomy and calculus. Early science, particularly geometry and astrology and astronomy, was connected to the divine for most medieval scholars, and many believed that there was something intrinsically "divine" or "perfect" that could be found in circles. It has been steeped in philosophical and religious exploration throughout history—in 300 BCE, book three of Euclid’s Elements dealt with the properties of circles; in 1700 BCE, the Rhind papyrus gives a method to find the area of a circular field; in 1880 CE, Lindermann proved that π or pie is transcendental, effectively settling the millennia-old problem of squaring the circle. The circle, believed by many, is the first theological emblem, marking not only the points of the solar calendar, but also used as an almost archetypal tool to communicate on both the material and the divine.

The works presented use the circle to examine a plethora of subjects; from works that address the notion of identity and tangibility of home, spirituality and duality of religious practices, astronomical occurrences and beliefs, and the realization of Euclidean geometry. The parallelism suggests a connection of meaning that echoes throughout matters that are either terrestrial or celestial in nature.