Musaed Al Hulis

The Seven Surfaces, 2015

Acryclic & Electric fuses

160 x 80 cm (62 15/16 x 31 7/16 in.)

Edition of 3

MAH0040

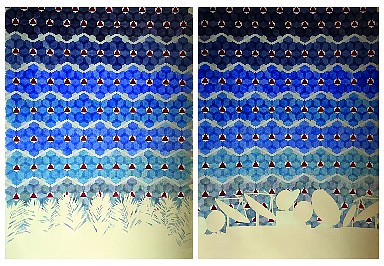

Daniah Al Saleh

Window with a View, 2015

WaterColour, Gouache and Pencil

127 x 85 cm (50 x 33 7/16 in.)

DAS0006

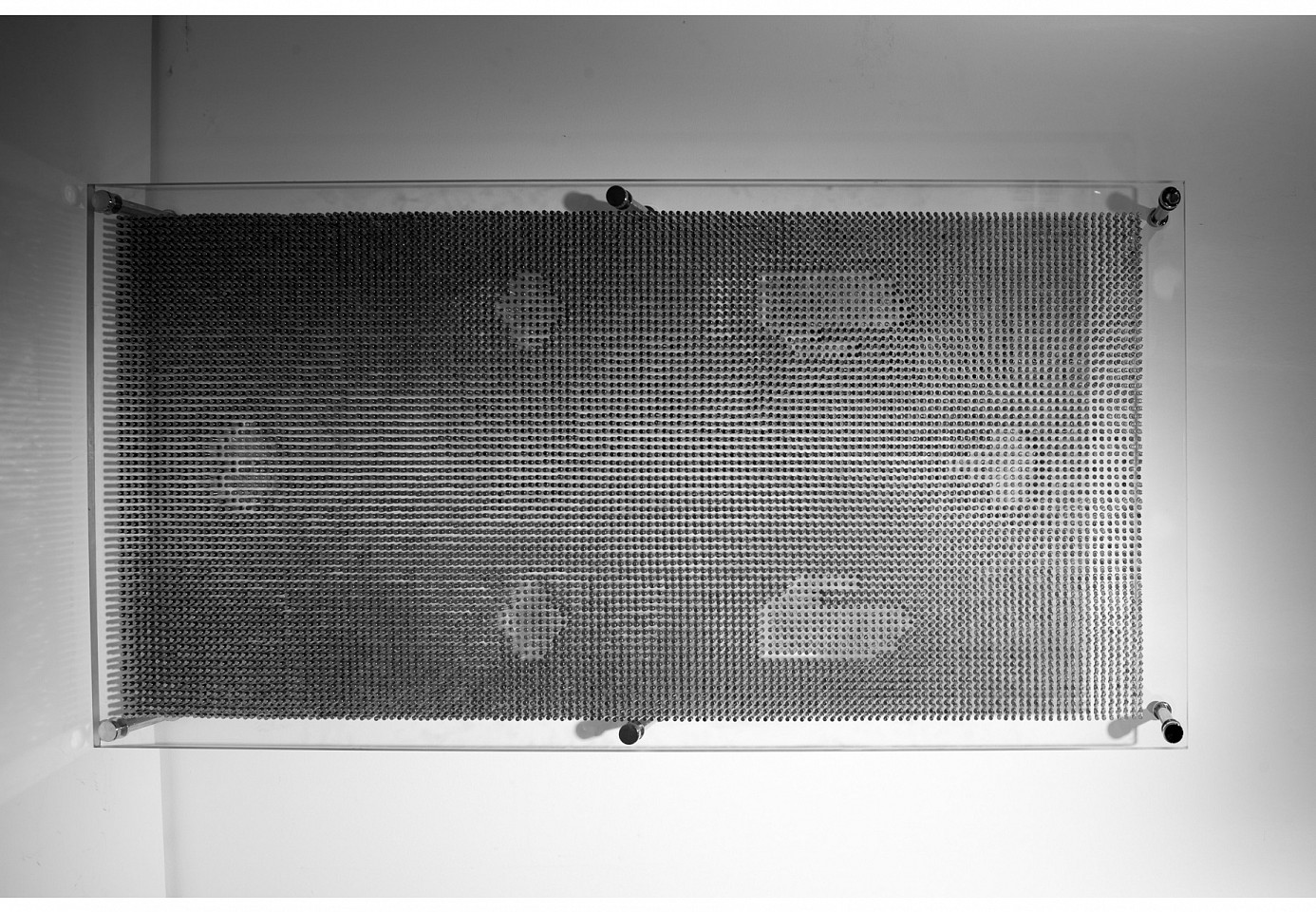

Nasser Al Salem

Kull VI, 2015

Print on layered Acrylic

110 x 110 x 15 cm (43 1/4 x 43 1/4 x 5 7/8 in.)

Edition of 5

NAS0248

Ziad Antar

Swings, 2013

Silver print mounted on dibond

120 x 120 cm (47 1/4 x 47 1/4 in.)

From Liminal Resolutions, Edition of 5 + 1 AP

ZIA0006

Ziad Antar

Axiom 06, 2012

Silver print mounted on dibond

120 x 120 cm (47 1/4 x 47 1/4 in.)

From Liminal Resolutions, Edition of 5 + 1 AP

ZIA0037

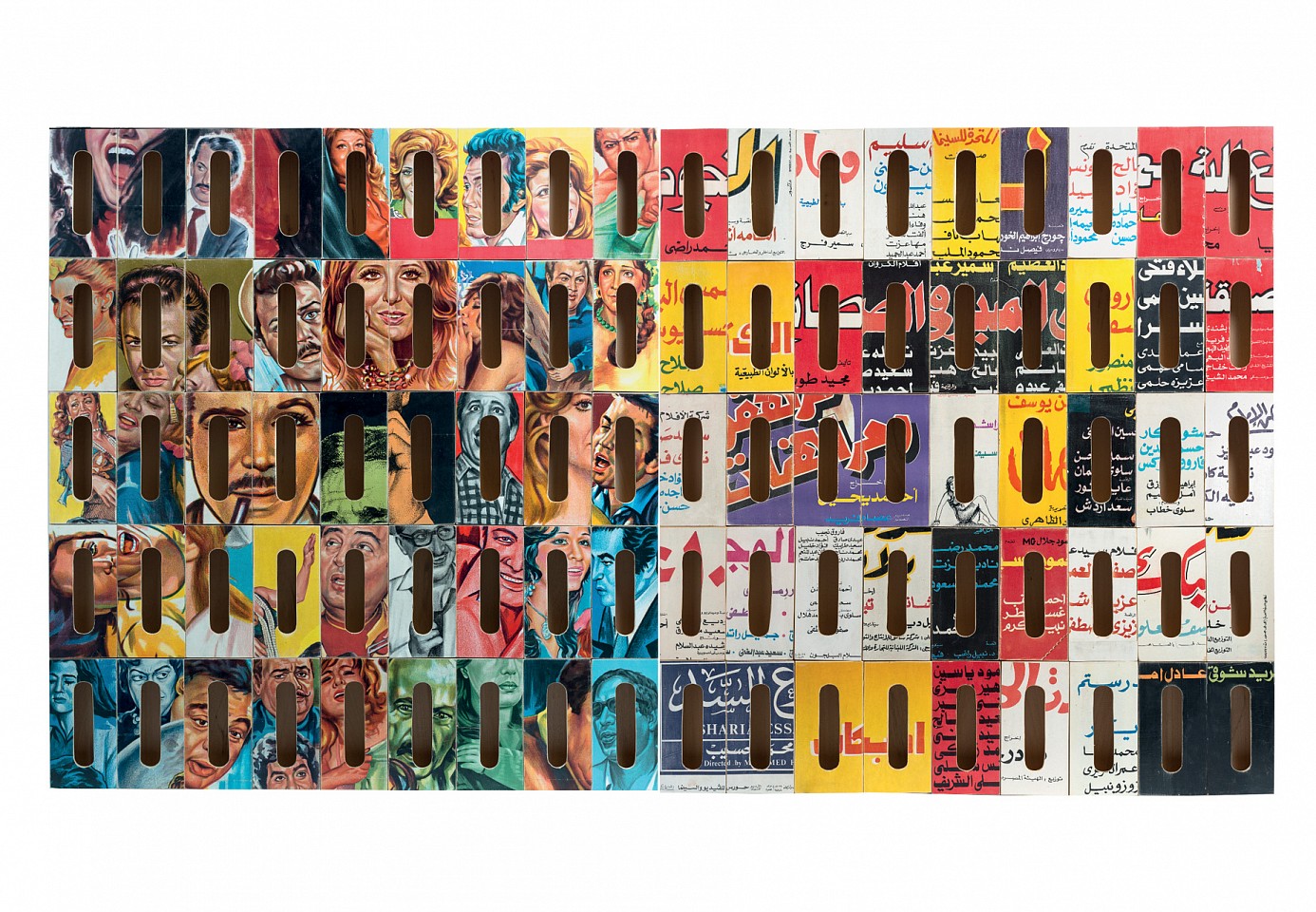

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Maharem II, 2015

45 Tissue Boxes

138 x 128 cm (54 5/16 x 50 3/8 in.)

AYD0508

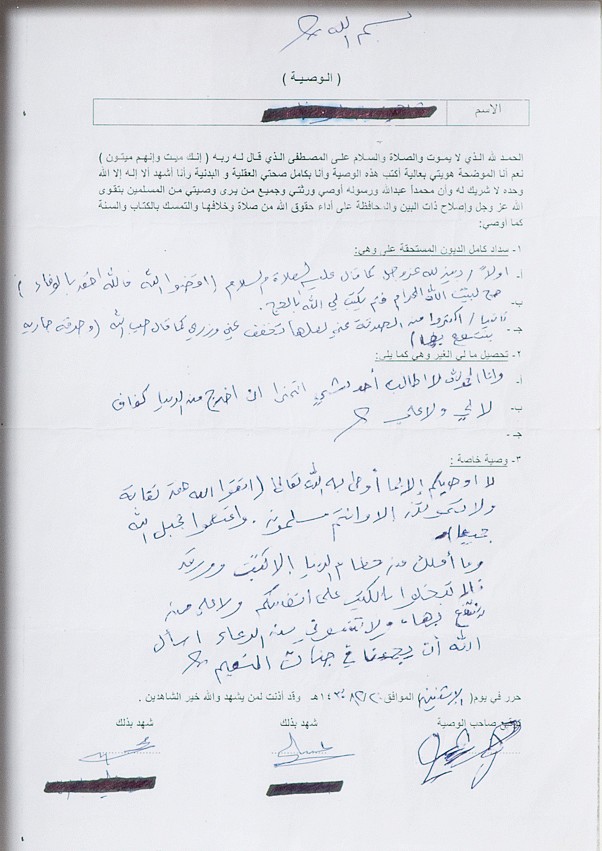

Abdulkarim Qassem

Wills of War, 2014

Work on paper

30 x 21 cm (11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in.)

ABQ0000

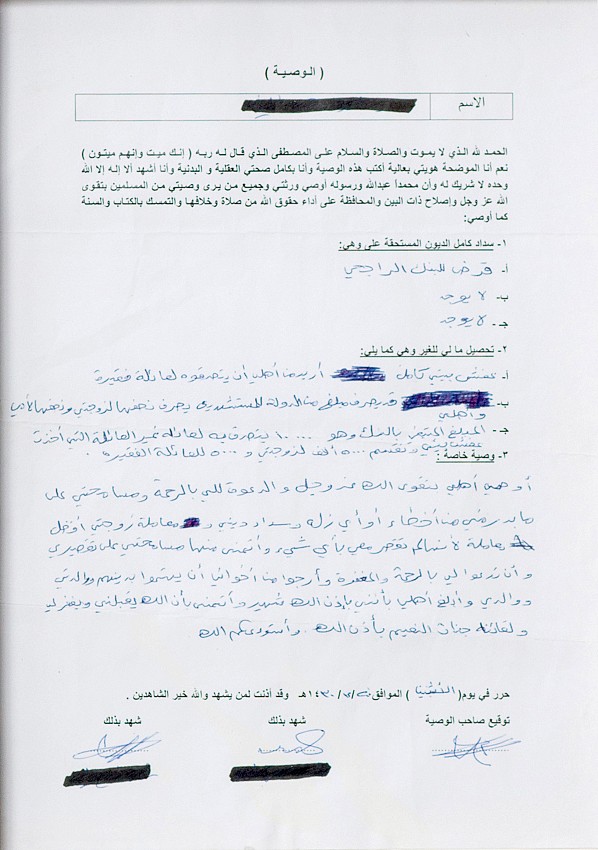

Abdulkarim Qassem

Wills of War 2, 2014

Work on paper

30 x 21 cm (11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in.)

ABQ0001

Saddek Wasil

Happily, I wrapped those painful bonds around me, 2014

Metal Sculpture / Car Paint

120 x 110 cm (47 3/16 x 43 1/4 in.)

From the Contortion Series

SAW0132

The piece is about the division in social class. Daniah used 2 typical views, one of rooftops and their haphazard TV dishes, the other is of a garden. Each View represents one social class. The more one is high on the social ladder, the better view one had. But humans have more things in common than not. We focus on eye level pleasures, but forget to look up and see we all share one sky, one heaven. The sky is represented symbolically by the 7 heavens, 7 devisions of different blues. The red triangles encourages the viewer to look up instead of downwards. Red being the colour of all humans, the colour of blood.

The direct translation of Kul is ‘all’ or ‘everything’. However, the connotation of the word Kul in the Arabic language is so much more complex in its all-encompassing meaning and implication of infinity. This meaning is compounded by the artist’s technique of calligraphically depicting the word Kul repeatedly, so that it resembles an endless ripple effect.

The impression of never-ending repetition is not merely a reflection of God’s abundance on Earth, but an indication to look both further, and deeper, to penetrate the mere appearance and surface of things, to discover the hidden messages that all aesthetic creation hold.

Once, we thought the atom was the smallest particle, before we discovered that it was made of numerous smaller ones, as we once thought that the extent of our universe was the Milky Way Galaxy, before we discovered that there were hundreds of billions more galaxies out there. As God’s creation is infinite, and while we can say or write the word ‘infinite’ easily, it is impossible to imagine as it extends far beyond the human brain’s capacity for comprehension. Therefore, if one thinks of Kul too deeply or for too long, they might realize that it doesn’t exist; there is no ‘all’ or ‘everything’.

The series Maharem originated from the tissue box which middle to lower income families traditionally exhibit in their sitting room for their guests’ convenience. These boxes are usually lavishly decorated with velvet and kitsch gold rims and are often considered decorative masterpieces, a source of pride to the lady of the house. The artist physically manipulates the tissue box, ripping it bare of the comfort of the velvet coating. He then prints movie imagery onto the rough wood, overlaying the scenes and portraits with the direct language of popular sayings, proverbs and riddles.

In Azkiya’a Laken Aghbiya’a, Daydban covers the boxes with fragments of film imagery – actors faces and shreds of titles, subtitles and names. The artist uses the language of fractured montage to reference the saturation of conflicting messaging we receive on a daily basis. Similar to a previous work entitled Love (2013), there is a visual harmony to the work when viewed from a distance, yet on closer inspection we are confronted with discord and uneasy interjections. The artist is commenting on notions of identity, he believes that societies in the Arab world are currently on an unknown trajectory – whilst waters seemingly move in one direction, underlying are currents of uncertainty and unrest. There is a suspense surrounding thoughts and notions of the future, the countries’ identities are being redefined and yet not one person is clear or in control of the proposed or possible conclusion. The only reliable constant in this world being the empathy between us, one for the other.