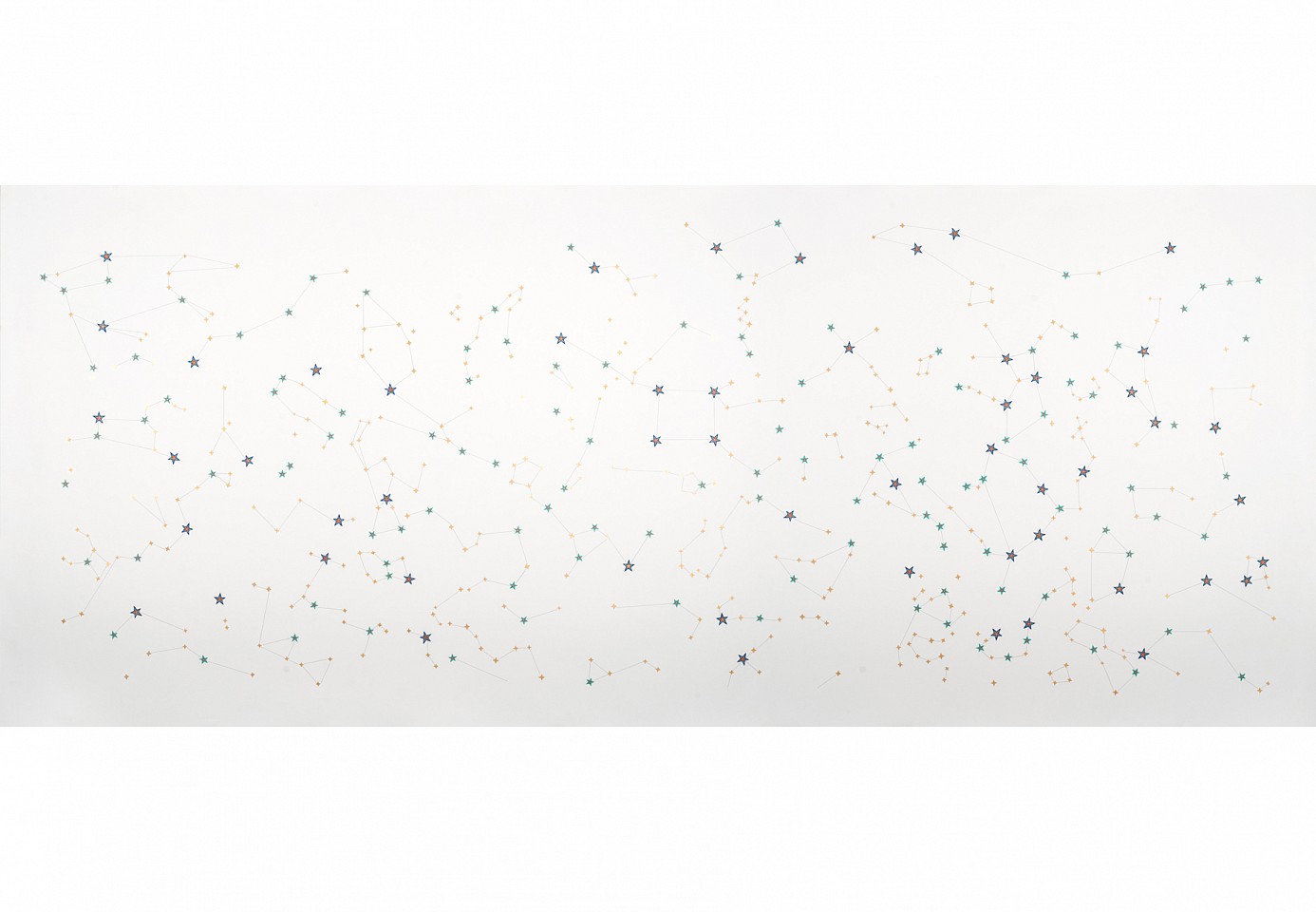

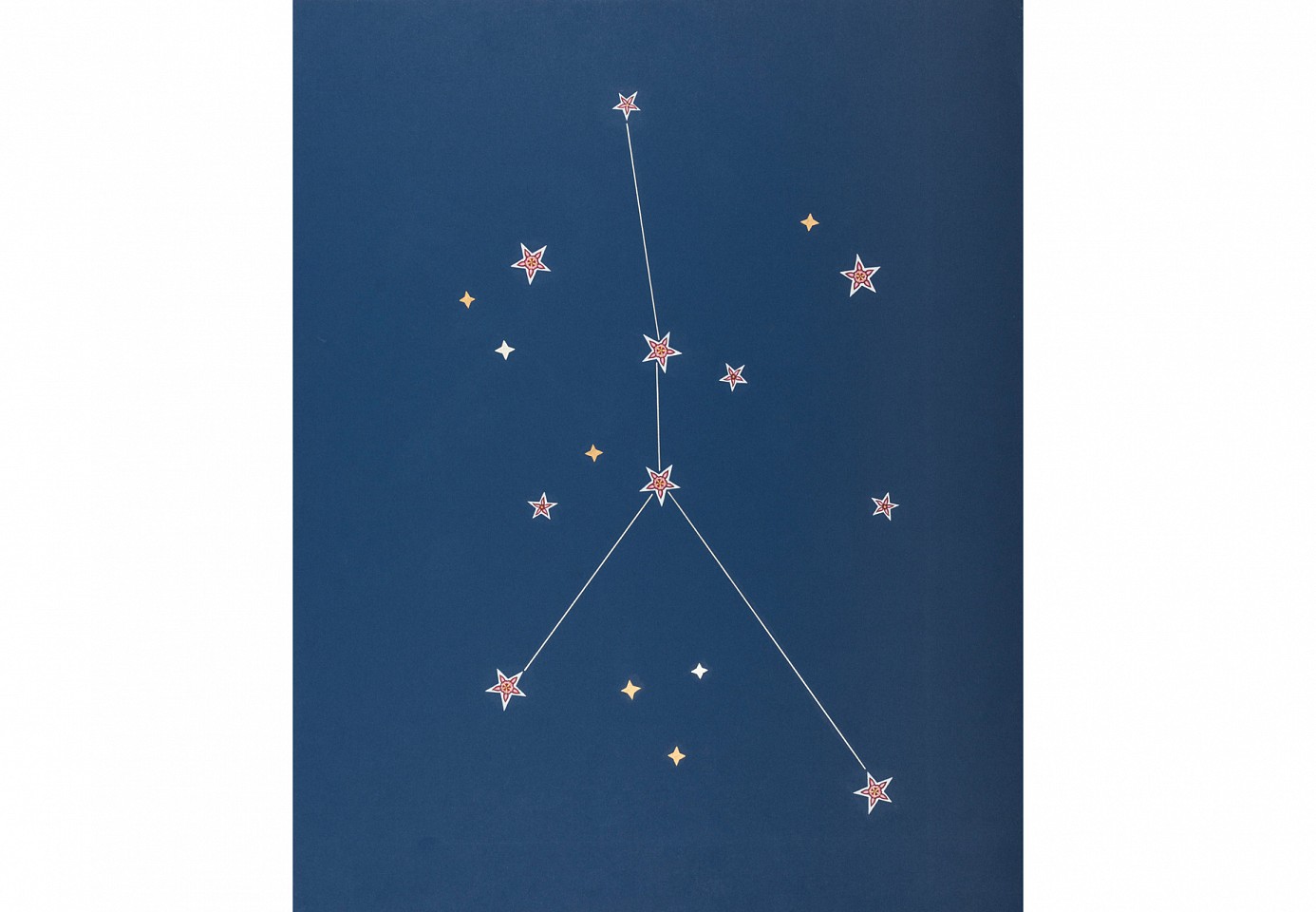

Dana Awartani

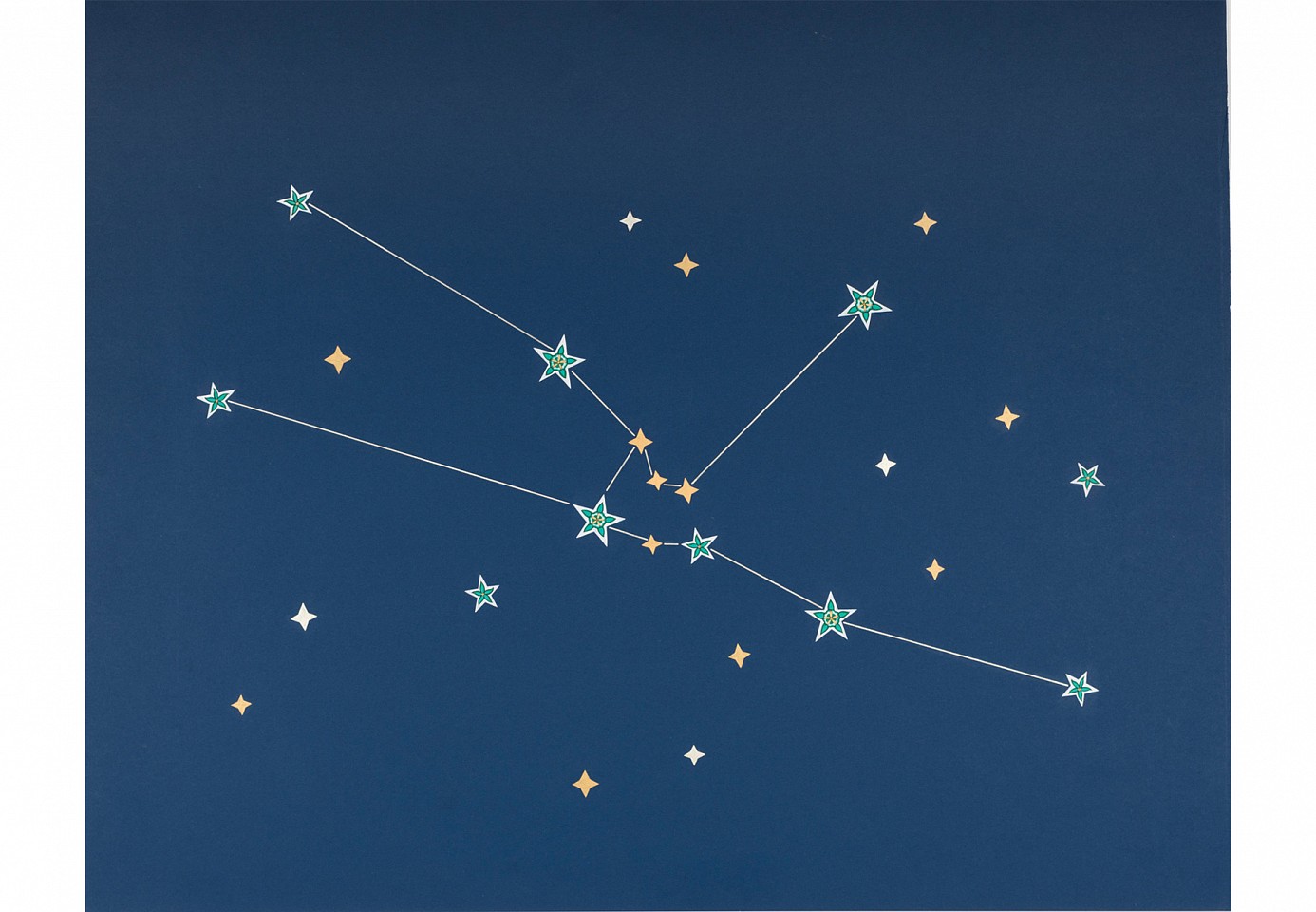

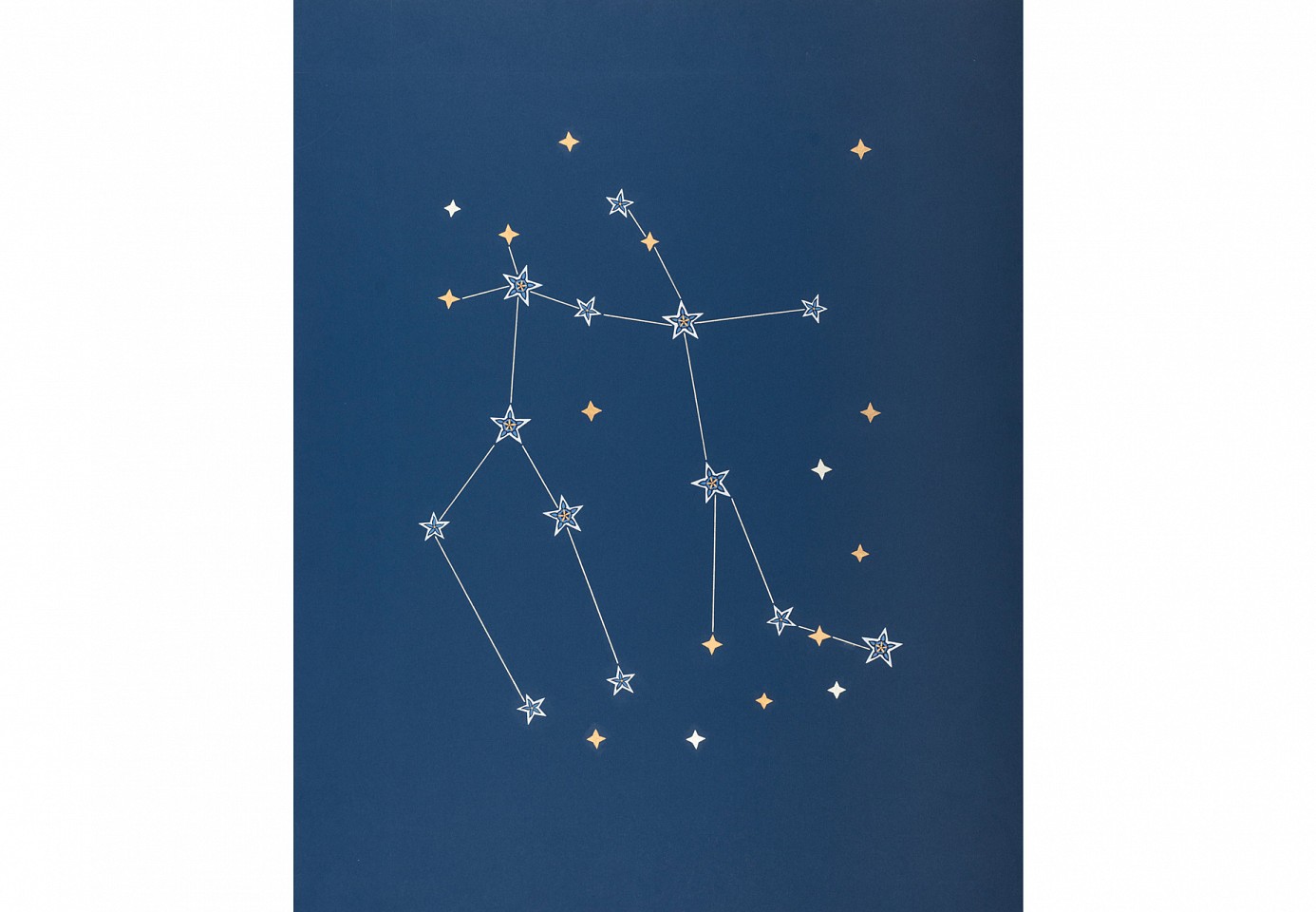

A Symphony of Stars, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

96 x 228 cm (37 3/4 x 89 3/4 in.)

DAN0069

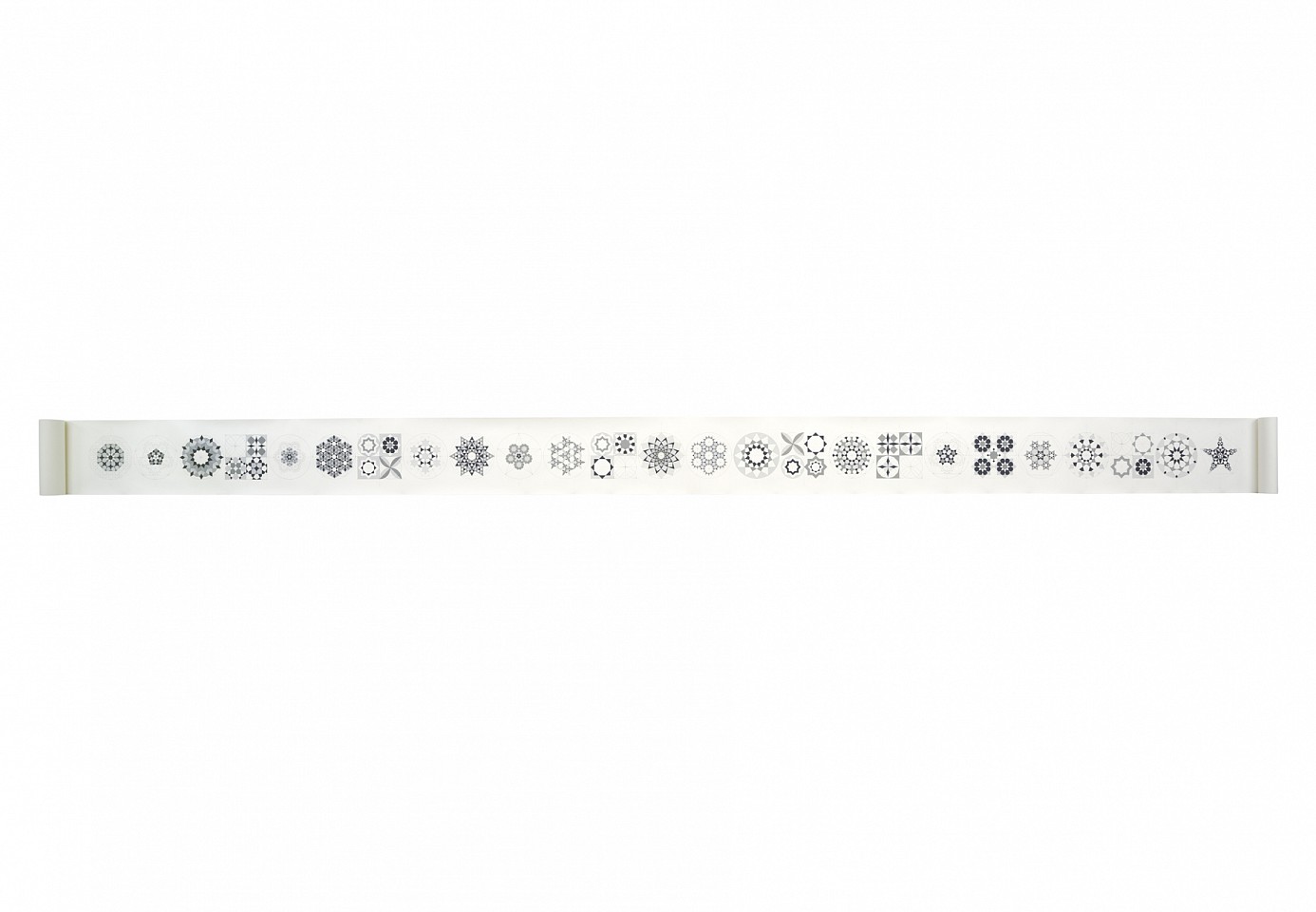

Dana Awartani

Scroll of The Prophets from the Abjad series, 2015

Gouache and ink on paper

42 x 681 cm (16 1/2 x 268 1/16 in.)

DAN0075

Dana Awartani

Acceptance from the Five Stages of Grief series, 2015

Embroidery on cotton

85 x 144 cm (33 7/16 x 56 11/16 in.)

DAN0070

Dana Awartani

Anger from the Five Stages of Grief series, 2015

Embroidery on cotton

85 x 144 cm (33 7/16 x 56 11/16 in.)

DAN0071

Dana Awartani

Bargaining from the Five Stages of Grief series, 2015

Embroidery on cotton

85 x 144 cm (33 7/16 x 56 11/16 in.)

DAN0072

Dana Awartani

Moon from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

59 x 59 cm (23 3/16 x 23 3/16 in.)

DAN0082

Dana Awartani

Sun from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

59 x 59 cm (23 3/16 x 23 3/16 in.)

DAN0079

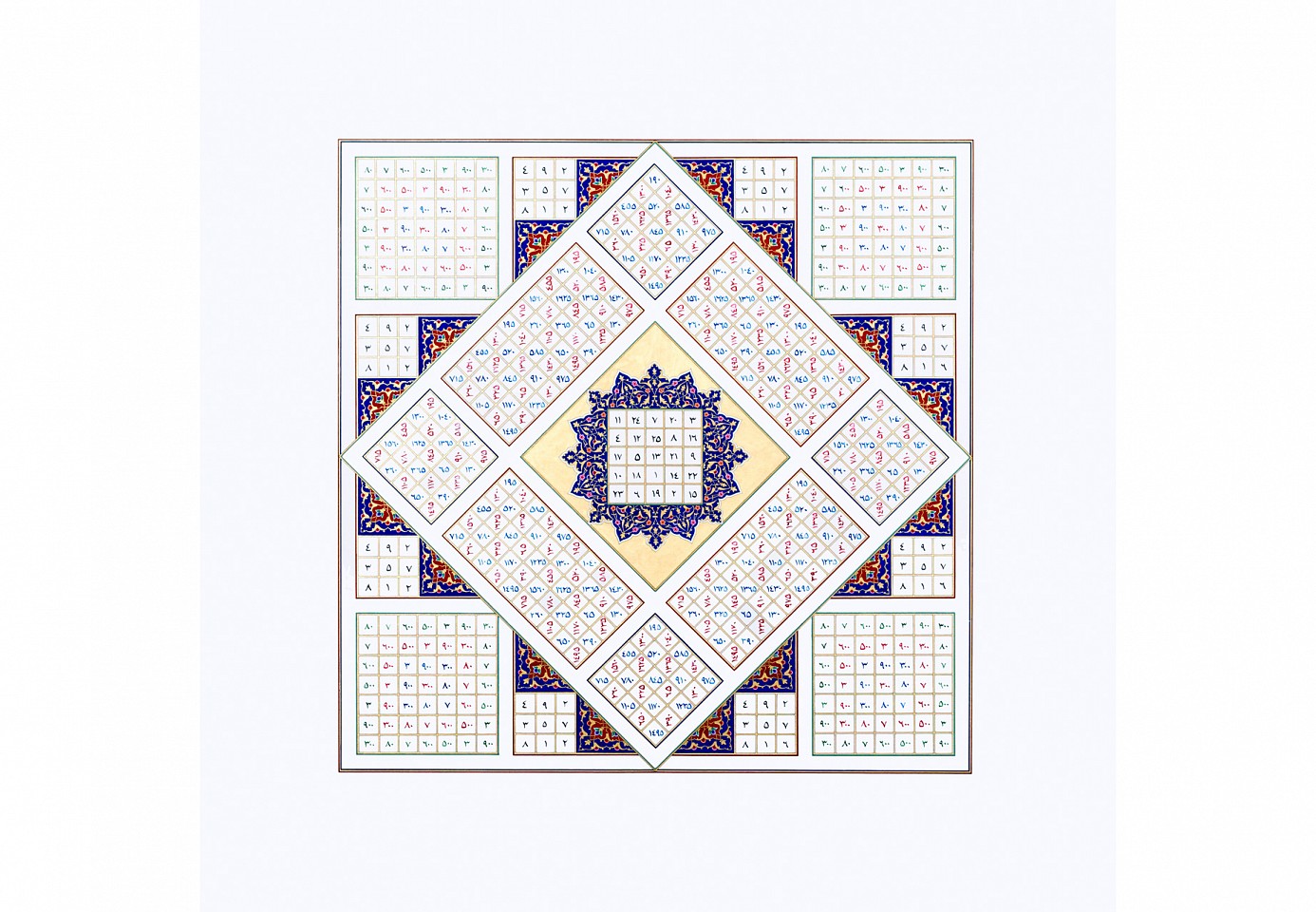

Dana Awartani

Mercury from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

59 x 59 cm (23 3/16 x 23 3/16 in.)

DAN0081

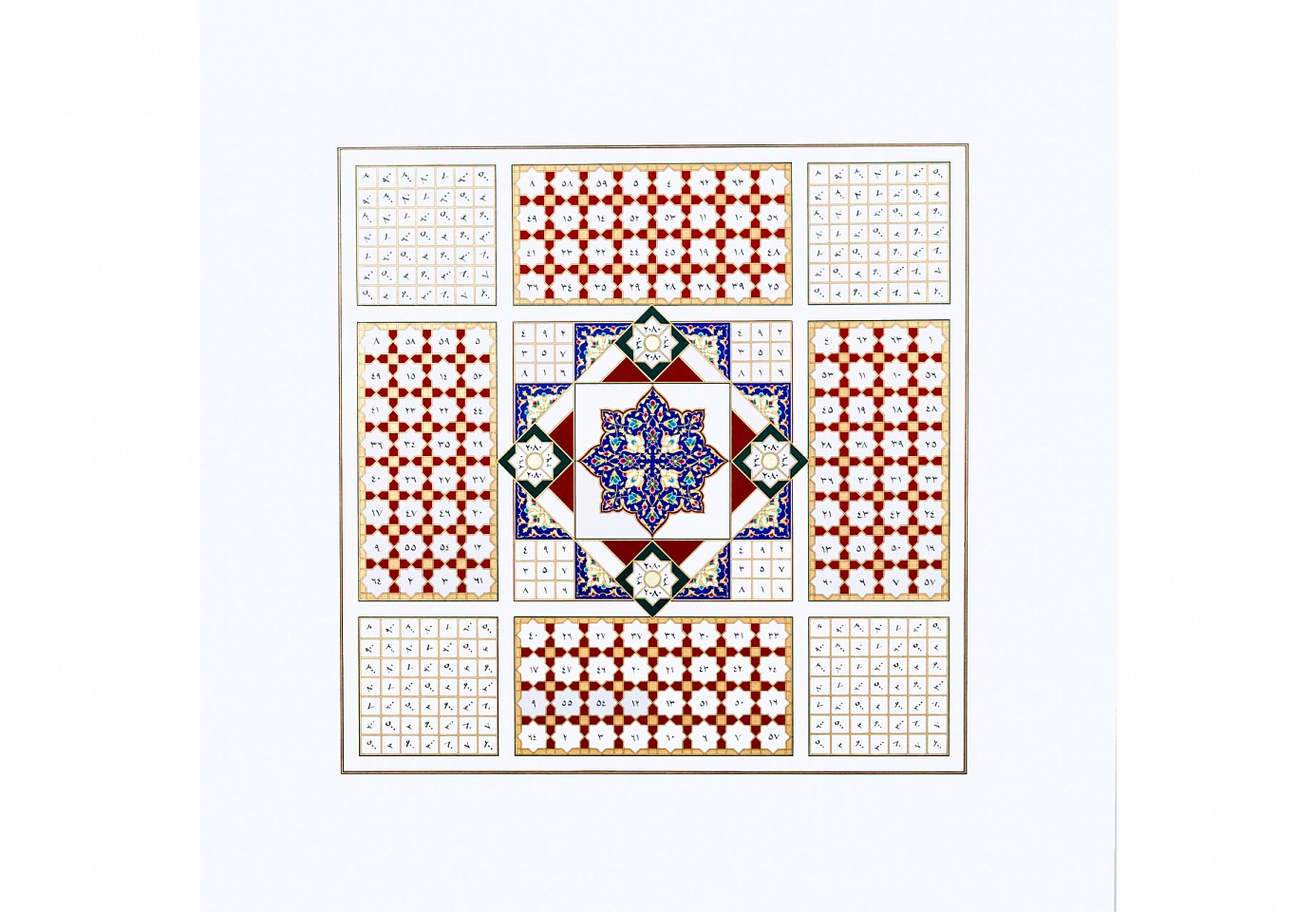

Dana Awartani

Mars from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

59 x 59 cm (23 3/16 x 23 3/16 in.)

DAN0078

Dana Awartani

Aries, 2015

Shell gold and gouache on paper

40.5 x 40.5 cm (15 15/16 x 15 15/16 in.)

DAN0088

Dana Awartani

Taurus, 2015

Shell gold and gouache on paper

40.5 x 40.5 cm (15 15/16 x 15 15/16 in.)

DAN0089

Dana Awartani

Gemini, 2015

Shell gold and gouache on paper

40.5 x 40.5 cm (15 15/16 x 15 15/16 in.)

DAN0090

Dana Awartani

Cancer, 2015

Shell gold and gouache on paper

40.5 x 40.5 cm (15 15/16 x 15 15/16 in.)

DAN0091

The Scroll of The Prophets, Awartani takes the names of all 25 prophets mentioned in the Qu’ran and translates them back to their numerical value using the Abjadia. She then constructs a geometric pattern for each prophet, layering the circles, squares, stars, triangles and hexagonal forms, placing one character (or individual) next to the other in a long scroll. Awartani uses these systems to allow physical manifestations of the prophets in an attempt to transcend the limitations placed on representational forms in Islam, bringing to the fore questions of idol worship.

In this system, each letter in the Arabic alphabet is given a numerical value, giving each name its own unique sum.

In her Five Stages of Grief series, Awartani uses the threads of talismanic references drawn from the Ottoman Empire and rooted in Islam to make connections to lost elements of Saudi heritage. The artist first encountered talismanic shirts in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul – pieces which were once said to protect the Sultans as they wore these kaftans before going to war and their wives during childbirth. The artist has taken original textiles from the Thageef tribe in Saudi, coded patterns which once denoted where a tribe came from. During the founding years of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, all such colourful and distinctive costumes were banished, with the neutral and harmonised black abaya and white kaftan encouraged for men and women, as a way of unifying the tribes. Stitched to the original garments are Awartani’s signature magic squares, where she has taken the five stages of grief and applied one stage to each garment. The artist has referenced to the ancient system used in divination where by the letters of the ‘abjad’ (A system in which each letter in the Arabic alphabet is given a numerical value, giving each name its own unique sum.) are divided into four parts and the seven letters in each part are assigned to one of the elements – air, fire, water and earth. Here she has created her own coded interpretation by attributing one of the elements to a specific stage of grief, with the last being a combination of all the elements, as these garments are intended to be seen as an aid to overcome the various emotions in the process of grieving. In this work, each symbol or letter of the language she has built is stitched into the cloth, the knots and ties intended as a reference to the sorrow implicit when layers of history are wiped out in the name of modernization. At the same time, the juxtaposition of old and new binds Awartani’s own complex reading of the world around her onto the ancient artifacts.

In her Five Stages of Grief series, Awartani uses the threads of talismanic references drawn from the Ottoman Empire and rooted in Islam to make connections to lost elements of Saudi heritage. The artist first encountered talismanic shirts in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul – pieces which were once said to protect the Sultans as they wore these kaftans before going to war and their wives during childbirth. The artist has taken original textiles from the Thageef tribe in Saudi, coded patterns which once denoted where a tribe came from. During the founding years of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, all such colourful and distinctive costumes were banished, with the neutral and harmonised black abaya and white kaftan encouraged for men and women, as a way of unifying the tribes. Stitched to the original garments are Awartani’s signature magic squares, where she has taken the five stages of grief and applied one stage to each garment. The artist has referenced to the ancient system used in divination where by the letters of the ‘abjad’ (A system in which each letter in the Arabic alphabet is given a numerical value, giving each name its own unique sum.) are divided into four parts and the seven letters in each part are assigned to one of the elements – air, fire, water and earth. Here she has created her own coded interpretation by attributing one of the elements to a specific stage of grief, with the last being a combination of all the elements, as these garments are intended to be seen as an aid to overcome the various emotions in the process of grieving. In this work, each symbol or letter of the language she has built is stitched into the cloth, the knots and ties intended as a reference to the sorrow implicit when layers of history are wiped out in the name of modernization. At the same time, the juxtaposition of old and new binds Awartani’s own complex reading of the world around her onto the ancient artifacts.

In her Five Stages of Grief series, Awartani uses the threads of talismanic references drawn from the Ottoman Empire and rooted in Islam to make connections to lost elements of Saudi heritage. The artist first encountered talismanic shirts in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul – pieces which were once said to protect the Sultans as they wore these kaftans before going to war and their wives during childbirth. The artist has taken original textiles from the Thageef tribe in Saudi, coded patterns which once denoted where a tribe came from. During the founding years of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, all such colourful and distinctive costumes were banished, with the neutral and harmonised black abaya and white kaftan encouraged for men and women, as a way of unifying the tribes. Stitched to the original garments are Awartani’s signature magic squares, where she has taken the five stages of grief and applied one stage to each garment. The artist has referenced to the ancient system used in divination where by the letters of the ‘abjad’ (A system in which each letter in the Arabic alphabet is given a numerical value, giving each name its own unique sum.) are divided into four parts and the seven letters in each part are assigned to one of the elements – air, fire, water and earth. Here she has created her own coded interpretation by attributing one of the elements to a specific stage of grief, with the last being a combination of all the elements, as these garments are intended to be seen as an aid to overcome the various emotions in the process of grieving. In this work, each symbol or letter of the language she has built is stitched into the cloth, the knots and ties intended as a reference to the sorrow implicit when layers of history are wiped out in the name of modernization. At the same time, the juxtaposition of old and new binds Awartani’s own complex reading of the world around her onto the ancient artifacts.

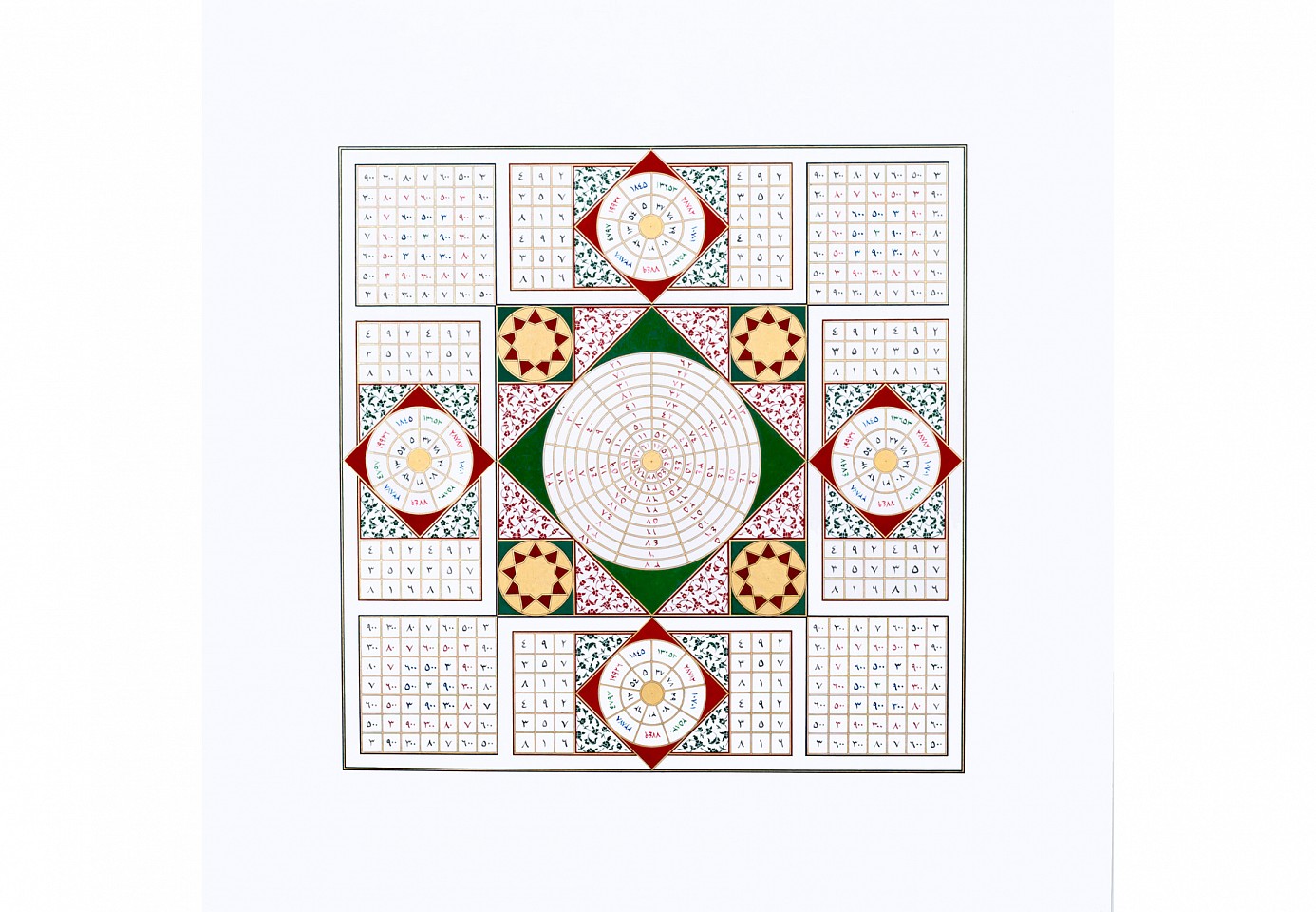

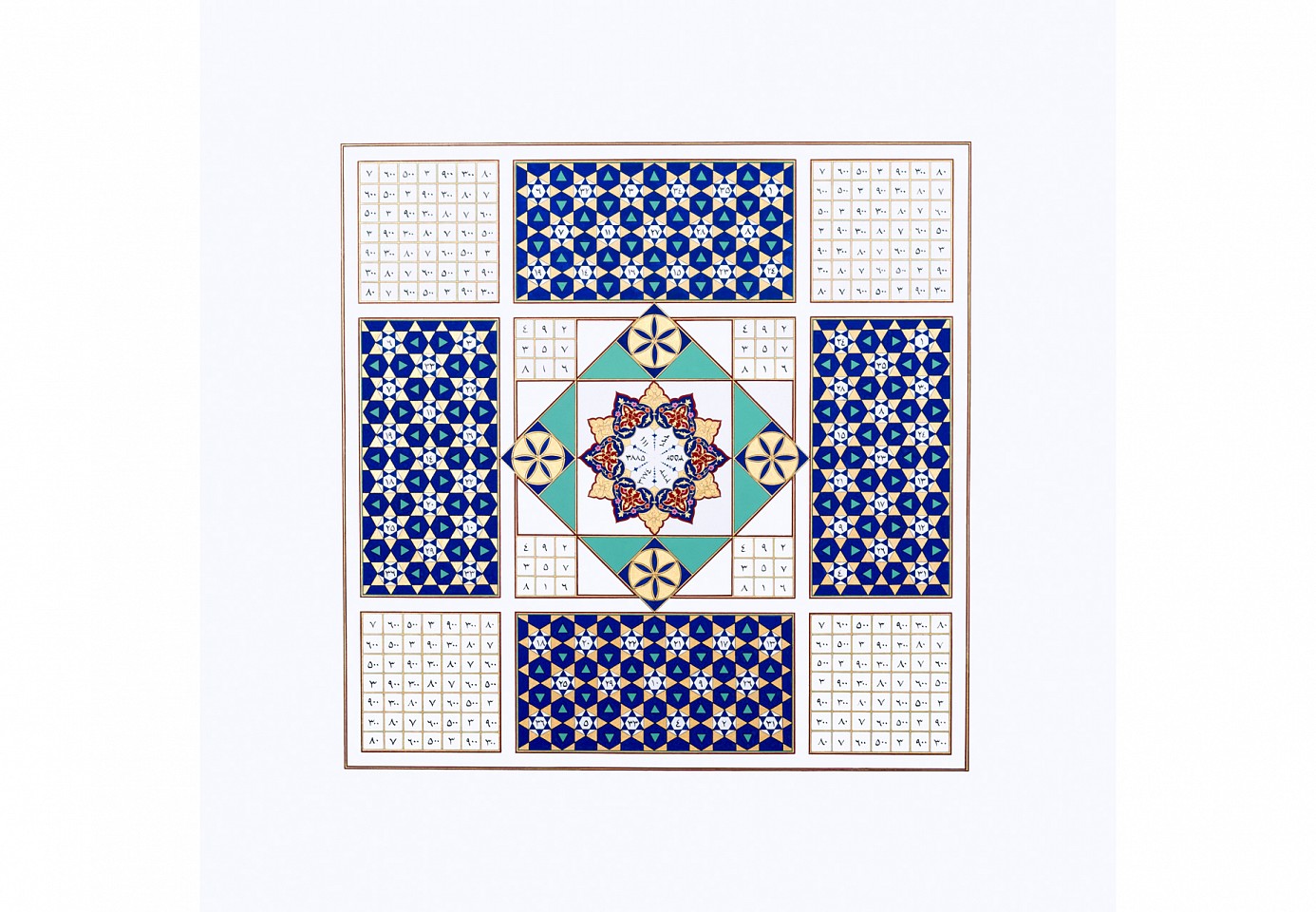

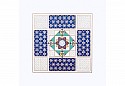

The Heavenly Bodies series combine Awartani’s research into both talismans and Enchanted squares, in particular an investigation into how they were created, used and their spiritual significance. Each of the central squares (from 3 to 9 squared) are affiliated with one of the seven classical planets, a day in the week and an angel – they were also once regarded as a form of protection as well as a source of higher spiritual knowledge through numerology. These works, created using traditional methods and pigments, are structured based on the first square, which sits at the top right of the work and holds the code to deciphering which planet has been illustrated.

Where once these coded paintings might have been used as designs for weavings on clothes, here they work as illuminations, with each of the seven works exploring form, pattern, numerology and mysticism, functioning almost as a manifestation of the artist’s explorations into the threads of divination in ancient Islam. By bringing these early practices into a contemporary and increasingly globalized context triggers questions surrounding the possible reversion to more instinctive rituals along with possible reinterpretations of the Qu’ran.

The Heavenly Bodies series combine Awartani’s research into both talismans and Enchanted squares, in particular an investigation into how they were created, used and their spiritual significance. Each of the central squares (from 3 to 9 squared) are affiliated with one of the seven classical planets, a day in the week and an angel – they were also once regarded as a form of protection as well as a source of higher spiritual knowledge through numerology. These works, created using traditional methods and pigments, are structured based on the first square, which sits at the top right of the work and holds the code to deciphering which planet has been illustrated.

Where once these coded paintings might have been used as designs for weavings on clothes, here they work as illuminations, with each of the seven works exploring form, pattern, numerology and mysticism, functioning almost as a manifestation of the artist’s explorations into the threads of divination in ancient Islam. By bringing these early practices into a contemporary and increasingly globalized context triggers questions surrounding the possible reversion to more instinctive rituals along with possible reinterpretations of the Qu’ran.

The Heavenly Bodies series combine Awartani’s research into both talismans and Enchanted squares, in particular an investigation into how they were created, used and their spiritual significance. Each of the central squares (from 3 to 9 squared) are affiliated with one of the seven classical planets, a day in the week and an angel – they were also once regarded as a form of protection as well as a source of higher spiritual knowledge through numerology. These works, created using traditional methods and pigments, are structured based on the first square, which sits at the top right of the work and holds the code to deciphering which planet has been illustrated.

Where once these coded paintings might have been used as designs for weavings on clothes, here they work as illuminations, with each of the seven works exploring form, pattern, numerology and mysticism, functioning almost as a manifestation of the artist’s explorations into the threads of divination in ancient Islam. By bringing these early practices into a contemporary and increasingly globalized context triggers questions surrounding the possible reversion to more instinctive rituals along with possible reinterpretations of the Qu’ran.

The Heavenly Bodies series combine Awartani’s research into both talismans and Enchanted squares, in particular an investigation into how they were created, used and their spiritual significance. Each of the central squares (from 3 to 9 squared) are affiliated with one of the seven classical planets, a day in the week and an angel – they were also once regarded as a form of protection as well as a source of higher spiritual knowledge through numerology. These works, created using traditional methods and pigments, are structured based on the first square, which sits at the top right of the work and holds the code to deciphering which planet has been illustrated.

Where once these coded paintings might have been used as designs for weavings on clothes, here they work as illuminations, with each of the seven works exploring form, pattern, numerology and mysticism, functioning almost as a manifestation of the artist’s explorations into the threads of divination in ancient Islam. By bringing these early practices into a contemporary and increasingly globalized context triggers questions surrounding the possible reversion to more instinctive rituals along with possible reinterpretations of the Qu’ran.

For her first solo exhibition at Athr, artist Dana Awartani shows three new projects intertwined by their exploration of ritual as gestures within which geometric and organic forms sit at the centre of a set of performed sequences acted out on paper and canvas. Each project questions the formalist and invariable interpretations of the Qu’ran prevalent in the Saudi judicial systems that sit opposed to more liberal undercurrents within contemporary Saudi society. The artist works with coding and geometric forms, including pre-Islamic talismanic designs and systems, to delineate her own process. For Awartani, who is studying towards her Ijazah, knowledge and understanding of the Qu’ran is implicit to her practice. She uses this to draw out and challenge underlying assumptions associated to the Islamic faith, plucking out rituals that straddle religions and behaviours, expounding their inherent possibilities across a multitude of neutral contexts.

The grant of permission represented by a certificate to indicate that one has been authorized to transmit a certain subject or text of Islamic knowledge.