Ahmed Mater

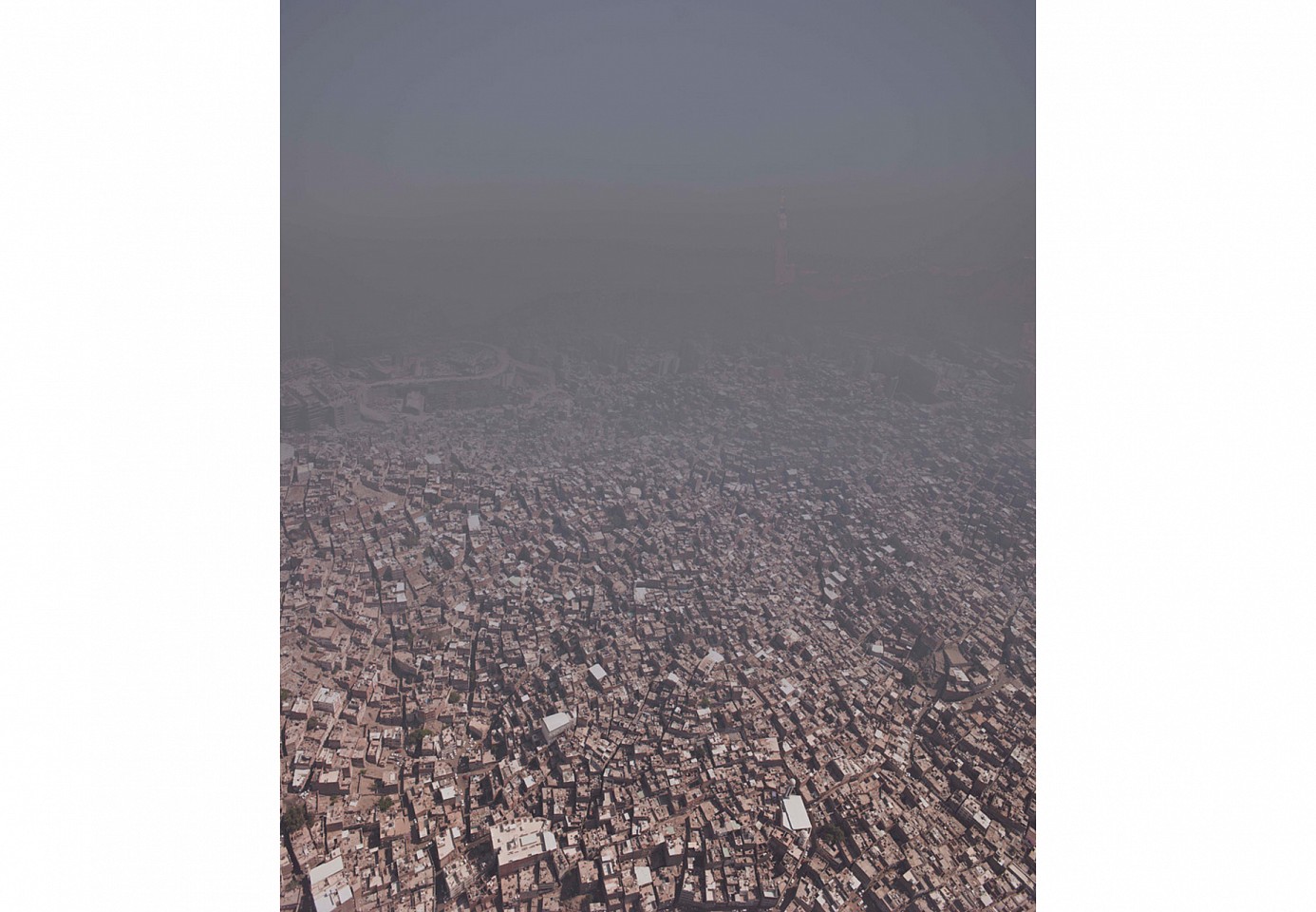

Nature Morte, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 143 cm (55 1/8 x 56 1/4 in.)

From Desert of Pharan series, Edition of 5

AHM0115

Ahmed Mater

From Real to the Symbolic City, 2012

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

245 x 292.5 cm (96 1/2 x 115 1/8 in.)

Edition of 3; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0061

Ahmed Mater

Golden Hour, 2011

Fineart Latex printer and matt 200g unbleached printing paper

245 x 326.5 cm (96 1/2 x 128 1/2 in.)

Edition of 3; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0017

Ahmed Mater

Leaves Fall in All Seasons, 2012

Video installation

Running Time 19:57 mins

From Desert of Pharan series, Edition of 5

AHM0135

Ahmed Mater

Ghost, 2013

Video installation

AHM0344

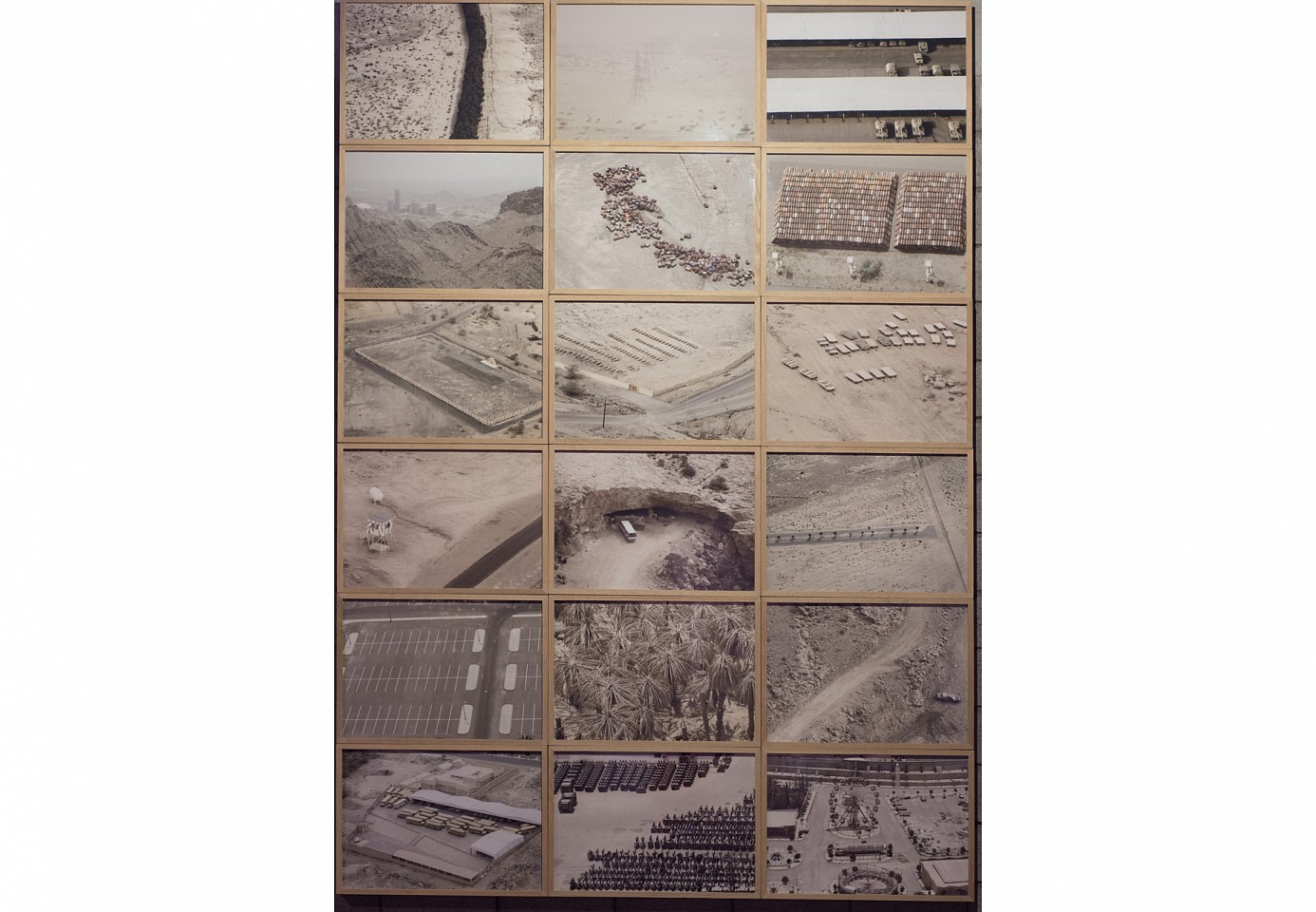

Ahmed Mater

Empty Lands, 2012

Photography (x18)

Edition of 3

AHM0112

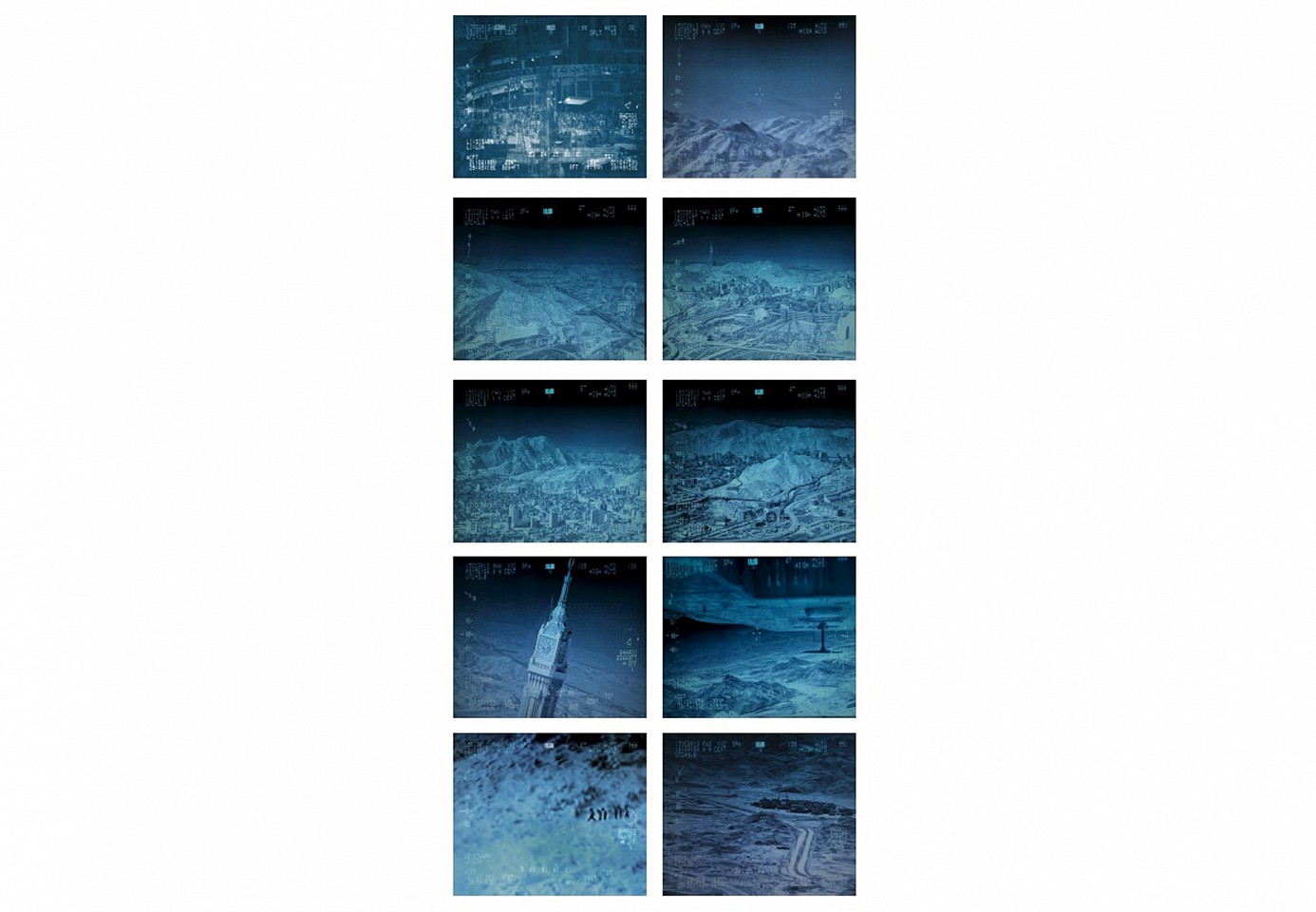

Ahmed Mater

Disarm, 2013

10 LED light boxes

31 x 37 cm (12 3/16 x 14 9/16 in.)

Edition of 5 + 1 AP, From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0189

Ahmed Mater

Antenna, 2010

Neon Tubes

150 x 150 x 50 cm (59 x 59 x 19 5/8 in.)

Edition of 2

AHM0008

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

- Naima Rashid

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

- Naima Rashid

Heading southeast out of Mecca, Mater encountered ceremonial drummers at a traditional wedding. Following the ebb and flow of one drummer's trance-like state, Mater remembered ominous tales of jinn, the restless spirits that live in the desert near " The dead city of Jahura ... midway between between the borders of Hejaz and Oman. There the sounds of drumming and moaning are regularly heard at night by passing travelers, by whom they are of course attributed to jinns or ghosts, persons of weak intellect having even been known to lose their reason." (Harry St.John Philby, Heart of Arabia: A Record of Travel & Exploration, 1922)

A Boy Stands on the flat, dusty rooftop of his family’s traditional house in the south west corner of Saudi Arabia. With all his reach he lifts a battered TV antenna up to the evening sky. He moves it slowly across the mountainous horizon, in search of a signal from beyond the nearby border with Yemen, or across the Red Sea towards Sudan. He is searching, like so many of his generation in Saudi, for ideas, for music, for poetry – for a glimpse of a different kind of life.

His father and brothers shout up from the majlis (sitting room) below, as music fills the house and dancing figures appear on a TV screen, filling the evening air with voices from another world. “This story says a lot about my life and my art” Ahmed tells me, as he installs a bright, white neon antenna into the ceiling of a warehouse gallery in Berlin. “I catch art from the story of my life,” he continues. “I don’t know any other way.”

Ahmed Mater is the boy with the antenna; a young explorer in search of contact with the outside world, reaching out to communicate across the borders that surround him. It is this spirit of creative exploration and curiosity that defines Ahmed’s journey as an artist.

Since the early 20th century, Saudi Arabia has experienced extraordinary political, economic and social transformation. Bringing together works by leading Saudi Arabian artist Ahmed Mater (b. 1979), “Symbolic Cities” offers unique perspectives on the effects of such changes on this country. This is the first and only showing of this exhibition in the United States solely dedicated to works by this artist; it will be on view at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery March 19–Sept. 18.

While Mater works in a variety of media, including painting, installations and performance,“Symbolic Cities: The Work of Ahmed Mater” will focus on his landscape photography as a means of exploring the tension between the traditional world and the realities of contemporary Saudi Arabian life. The exhibition will highlight three journeys through Saudi Arabia, with an eye toward the impact of urbanization—“Empty Land,” “Desert of Pharan” (2011-13) and “Ashab Al-Lal/Fault Mirage” (2015). Beginning with his aerial views of abandoned desert sites and continuing through the reconstruction of Mecca, a series of large-scale photographs and videos are organized as an experiential encounter, a progression from quiet emptiness to the physical and emotional intensity of the changes Mater is witnessing. The exhibition culminates with the installation “Ashab Al-Lal/Fault Mirage: A Thousand Lost Years,” the first chapter in Mater’s latest project examining the growth of Riyadh, the country’s administrative capital and largest city.

“Mater brings the rigor of his training as a physician—as well as unparalleled access—to gather frank observations of his own time and place,” said exhibition curator Carol Huh, the Freer|Sackler’s curator for contemporary art. “The resulting imagery is straightforward and striking, while his newest research-based project presents another fascinating shift in his use of the photographic medium.”

“Symbolic Cities” is the second in a series of exhibitions highlighting artists and works in Freer|Sackler’s growing collection of contemporary photography.

“Symbolic Cities: The Work of Ahmed Mater” is organized by the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, in collaboration with Culturunners in partnership with Art Jameel, a Community Jameel initiative.

The Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., together comprise the nation’s museum of Asian art. It contains one of the most important collections of Asian art in the world, featuring more than 40,000 objects ranging in time from the Neolithic to the present day, with especially fine groupings of Islamic art, Chinese jades, bronzes and paintings and the art of the ancient Near East. The galleries also contain important masterworks from Japan, ancient Egypt, South and Southeast Asia and Korea, as well as the Freer’s noted collection of works by American artist James McNeill Whistler. The Freer Gallery of Art, which will be closed during this exhibition, is scheduled to reopen in spring 2017 with modernized technology and infrastructure, refreshed gallery spaces and an enhanced Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer Auditorium.