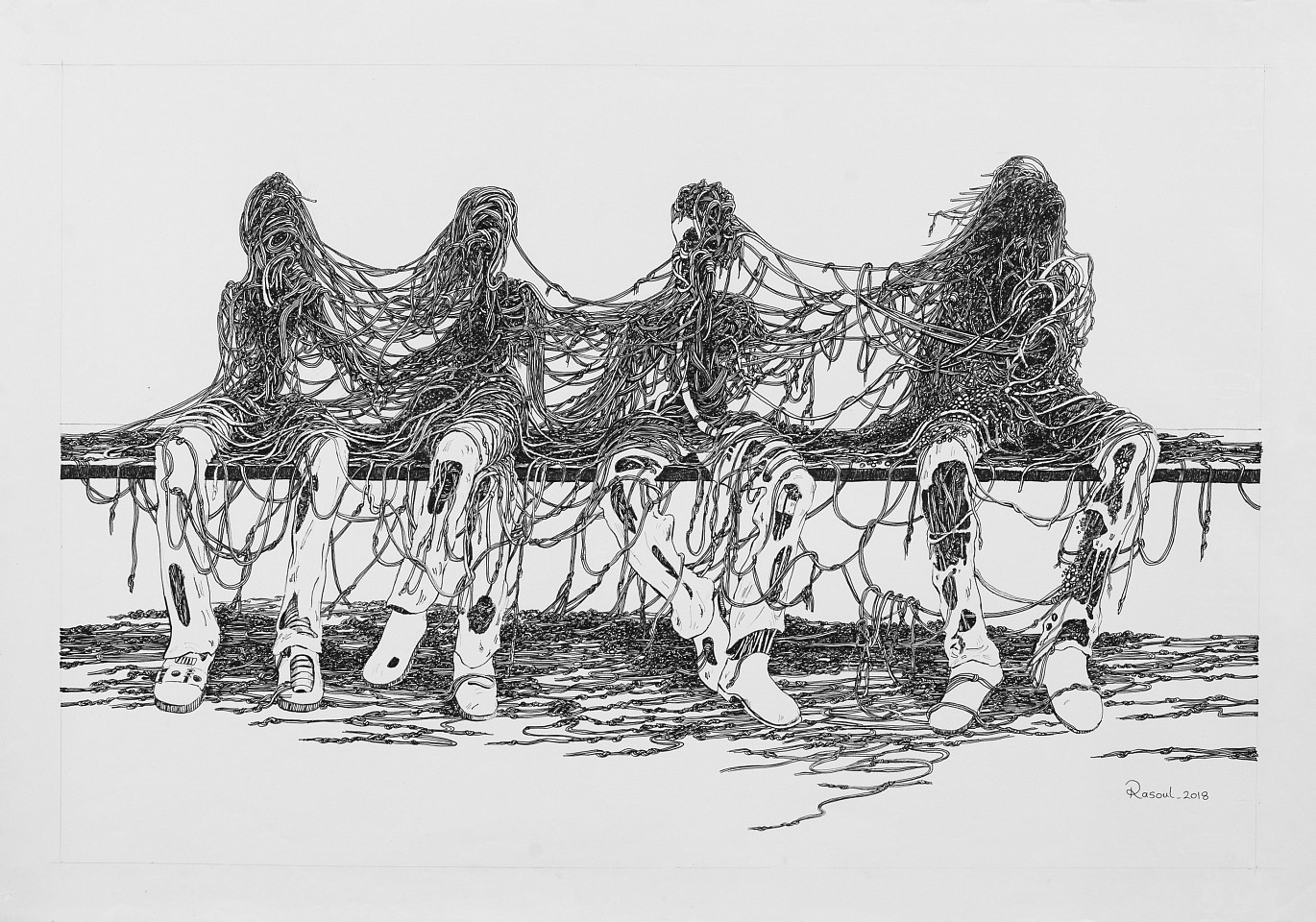

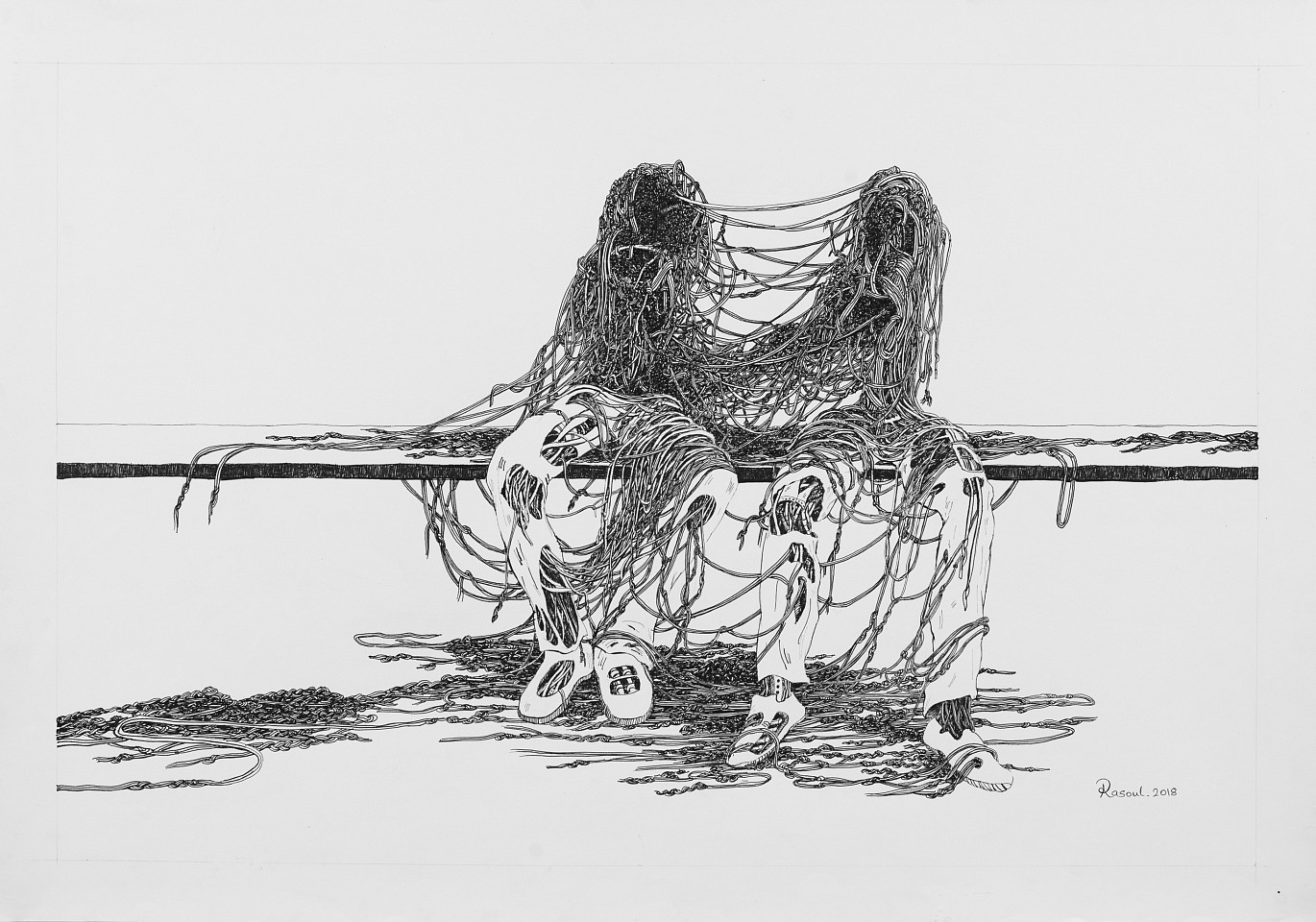

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.1, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0041

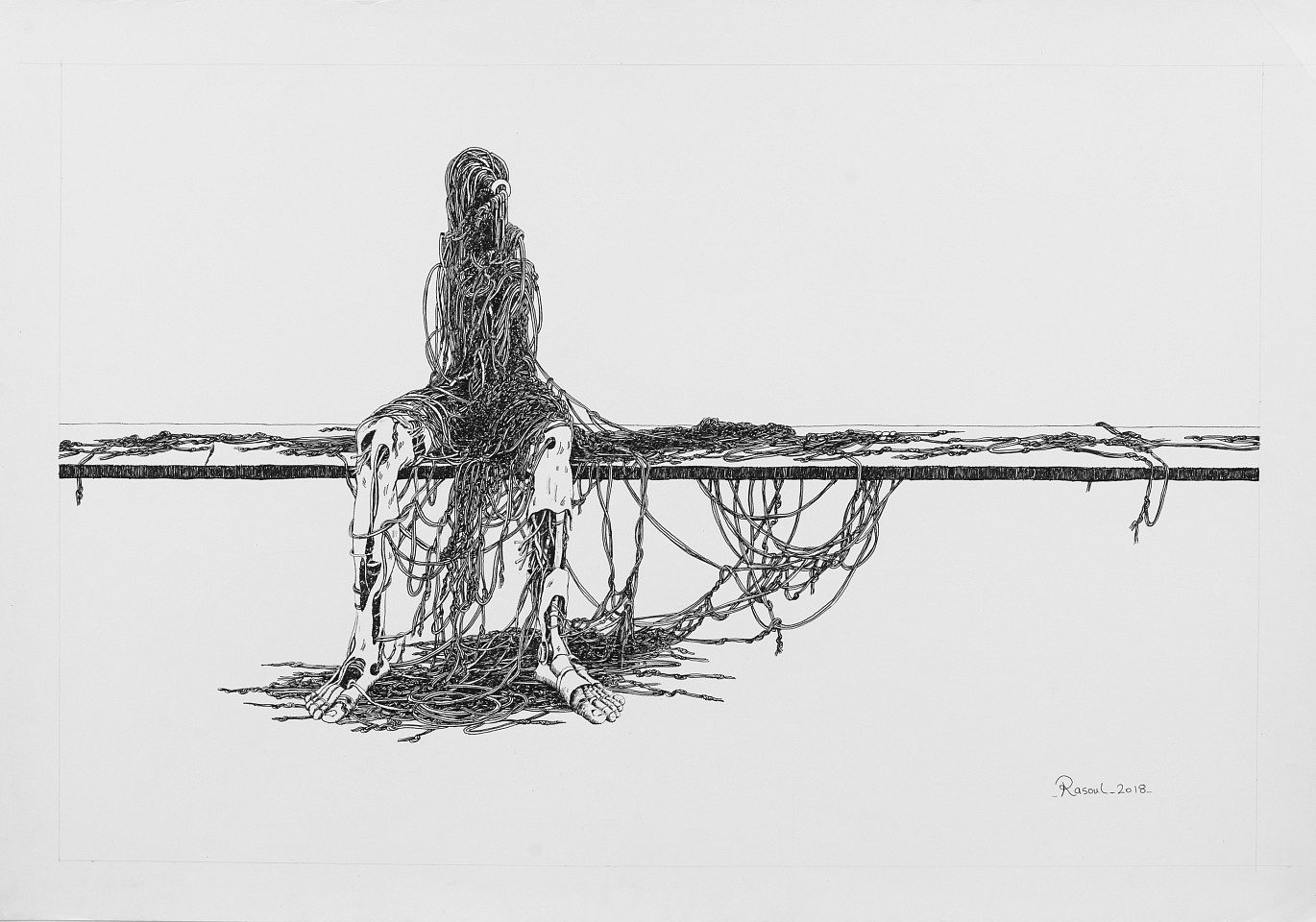

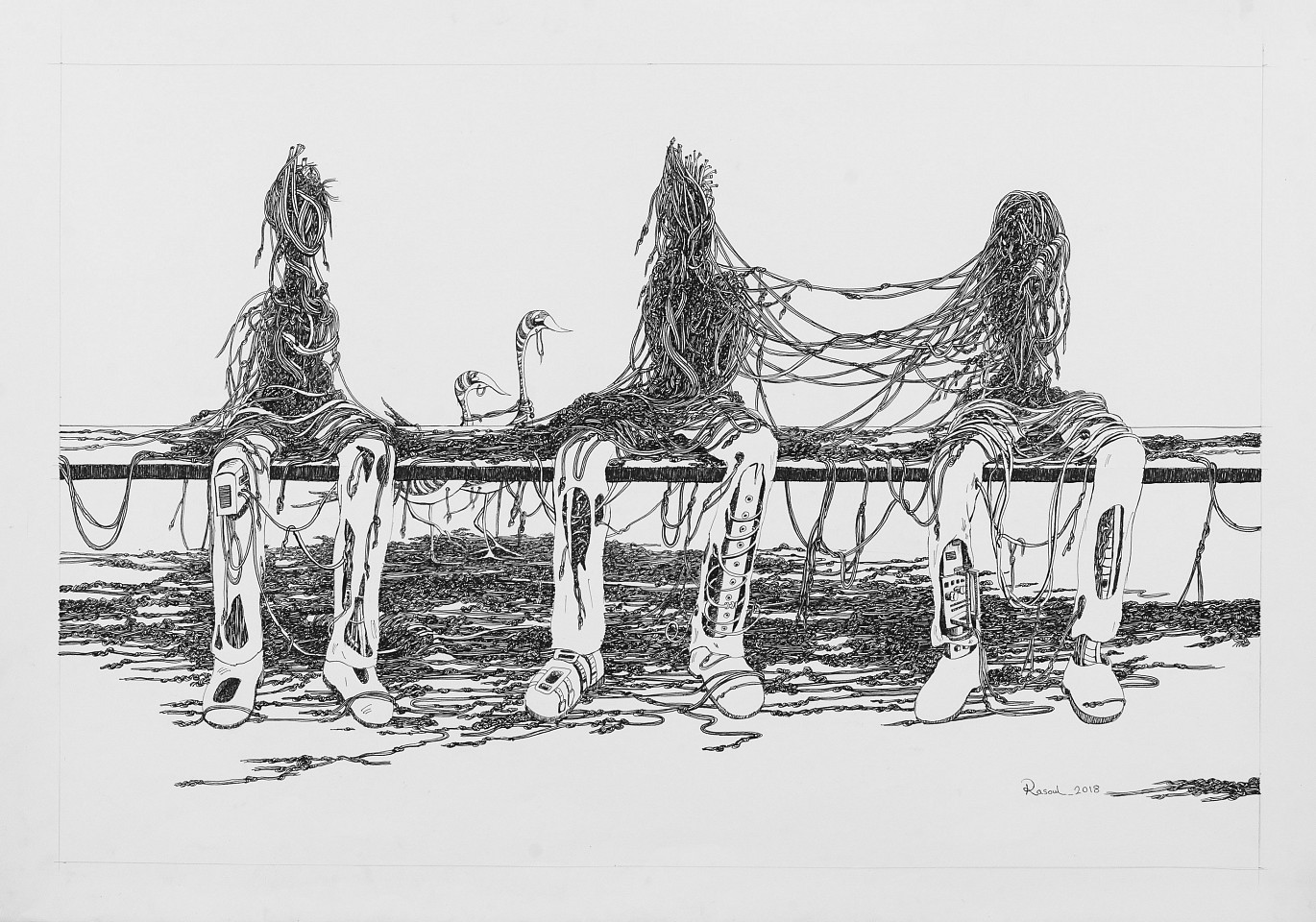

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.10, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0050

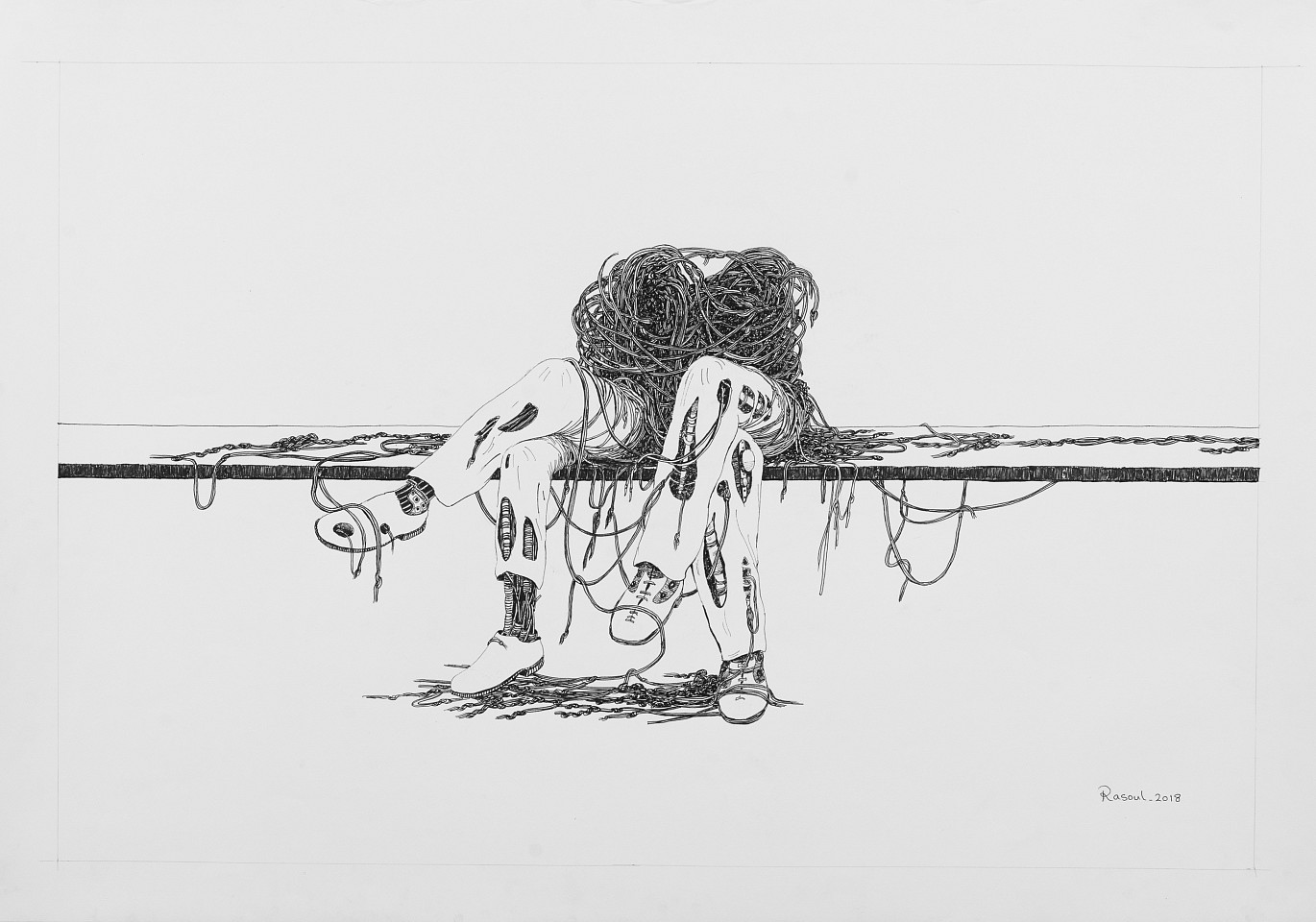

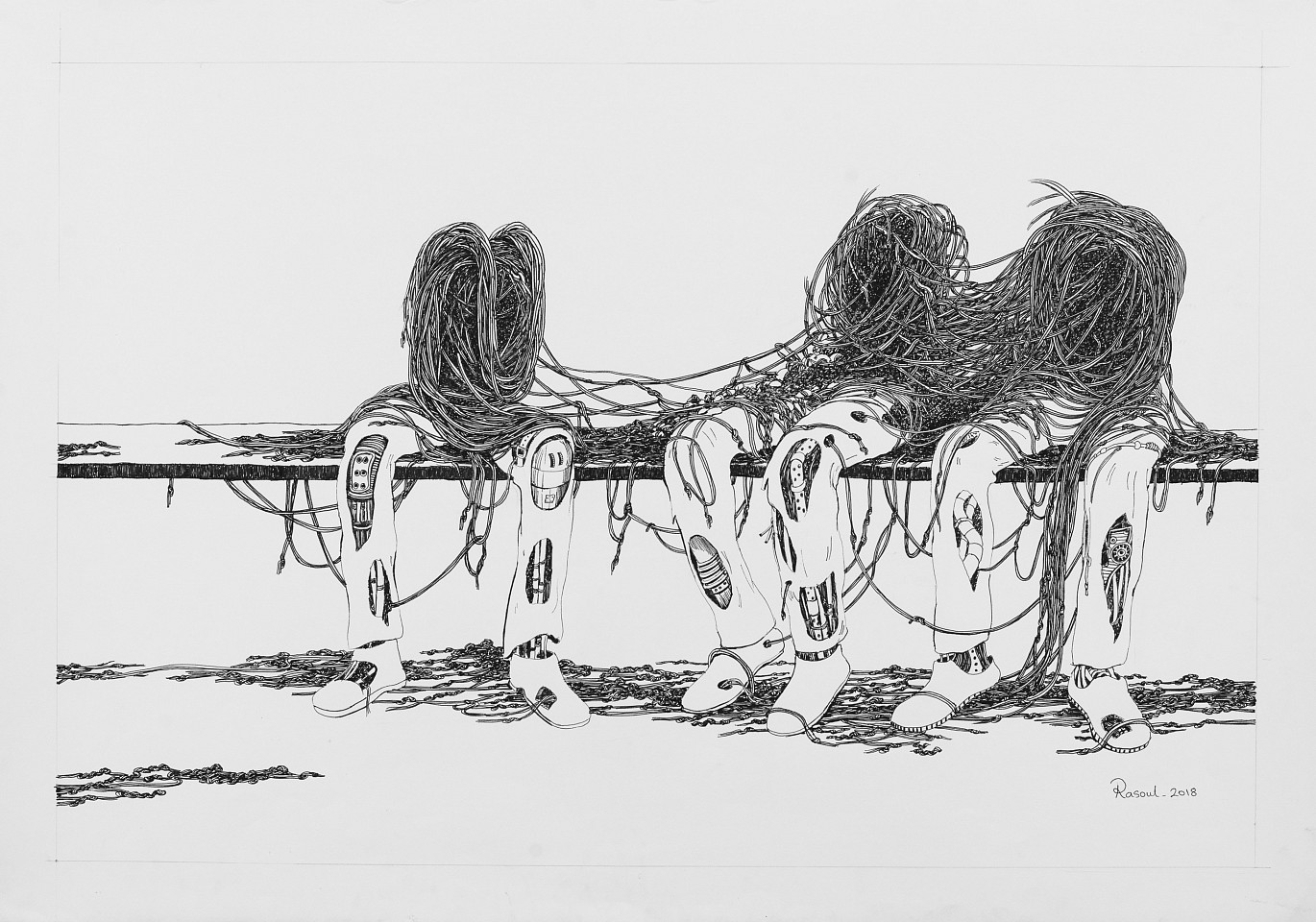

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.2, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0042

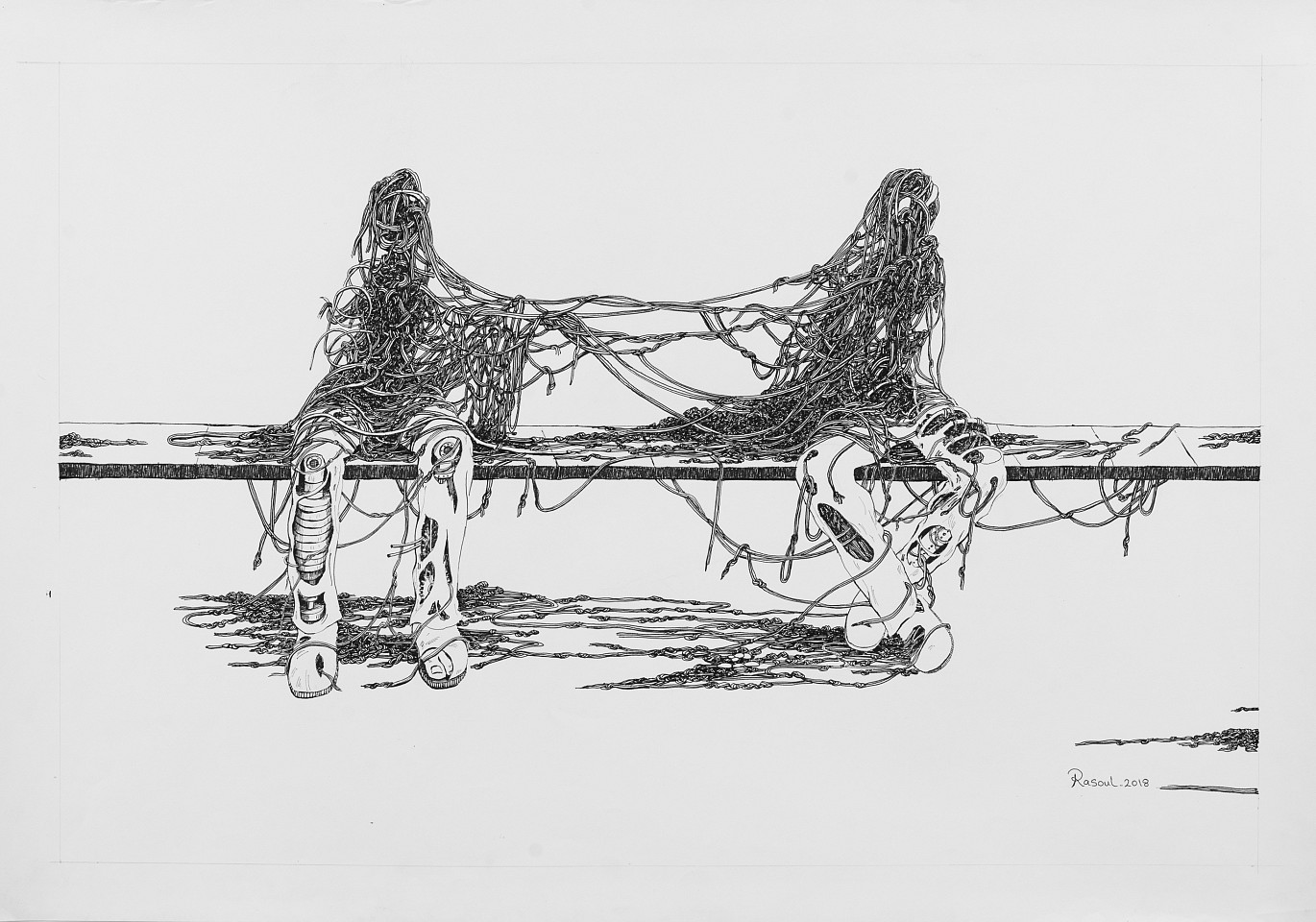

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.3, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0043

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.4, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0044

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.5, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0045

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.6, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0046

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.7, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0047

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.8, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0048

Mohamed AbdelRasoul

v1.9, 2018

Ink on Paper

MAR0049

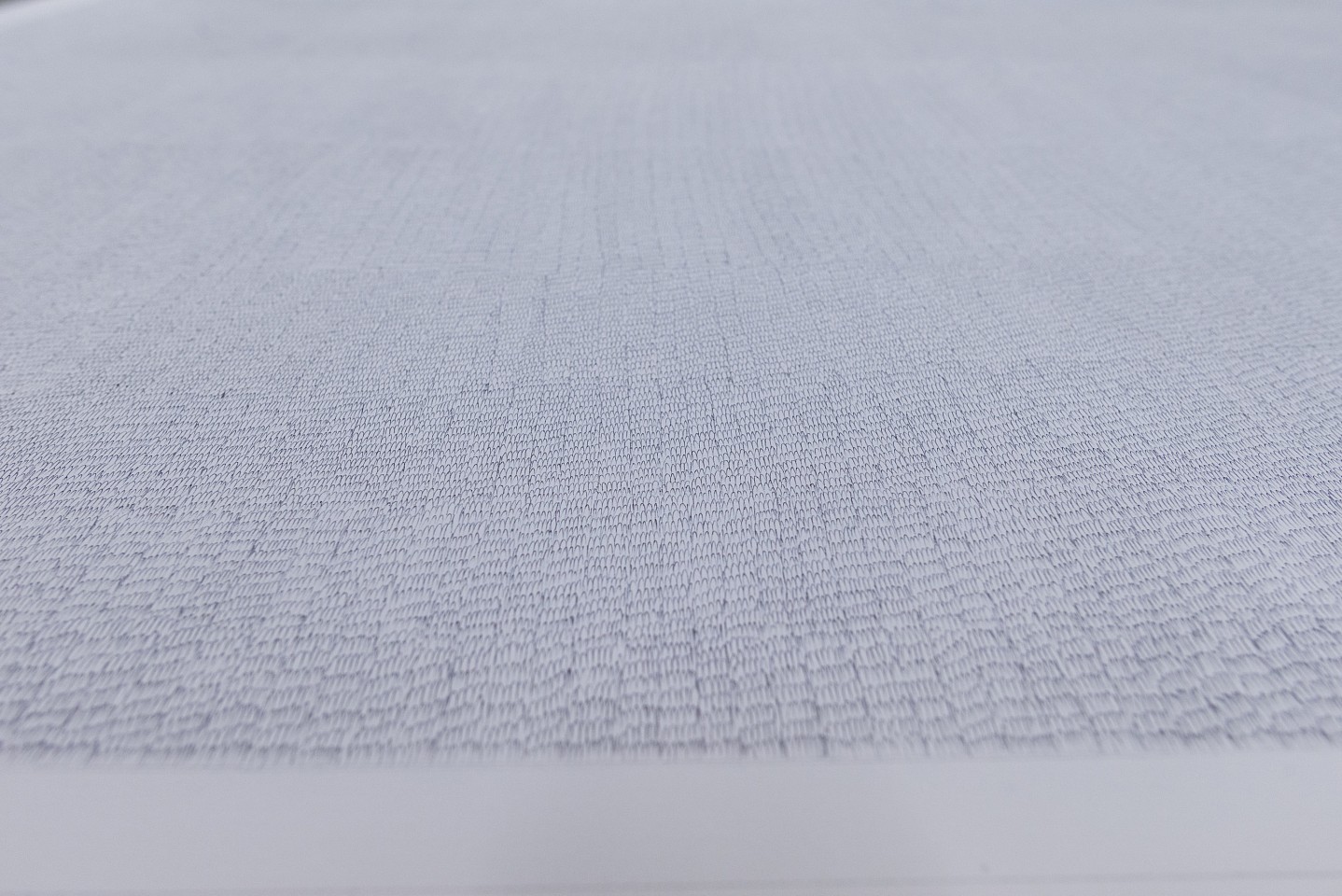

Sara Abdu

Communing with the self, as I commune with Him, 2018

Black ink on paper

SAB0116

Mohammed Al Faraj

Sophia, 2018

Video installation

MAF0001

Nasser Al Salem

Amma Ba'ad, 2018

Aluminum and black paint

NAS0462

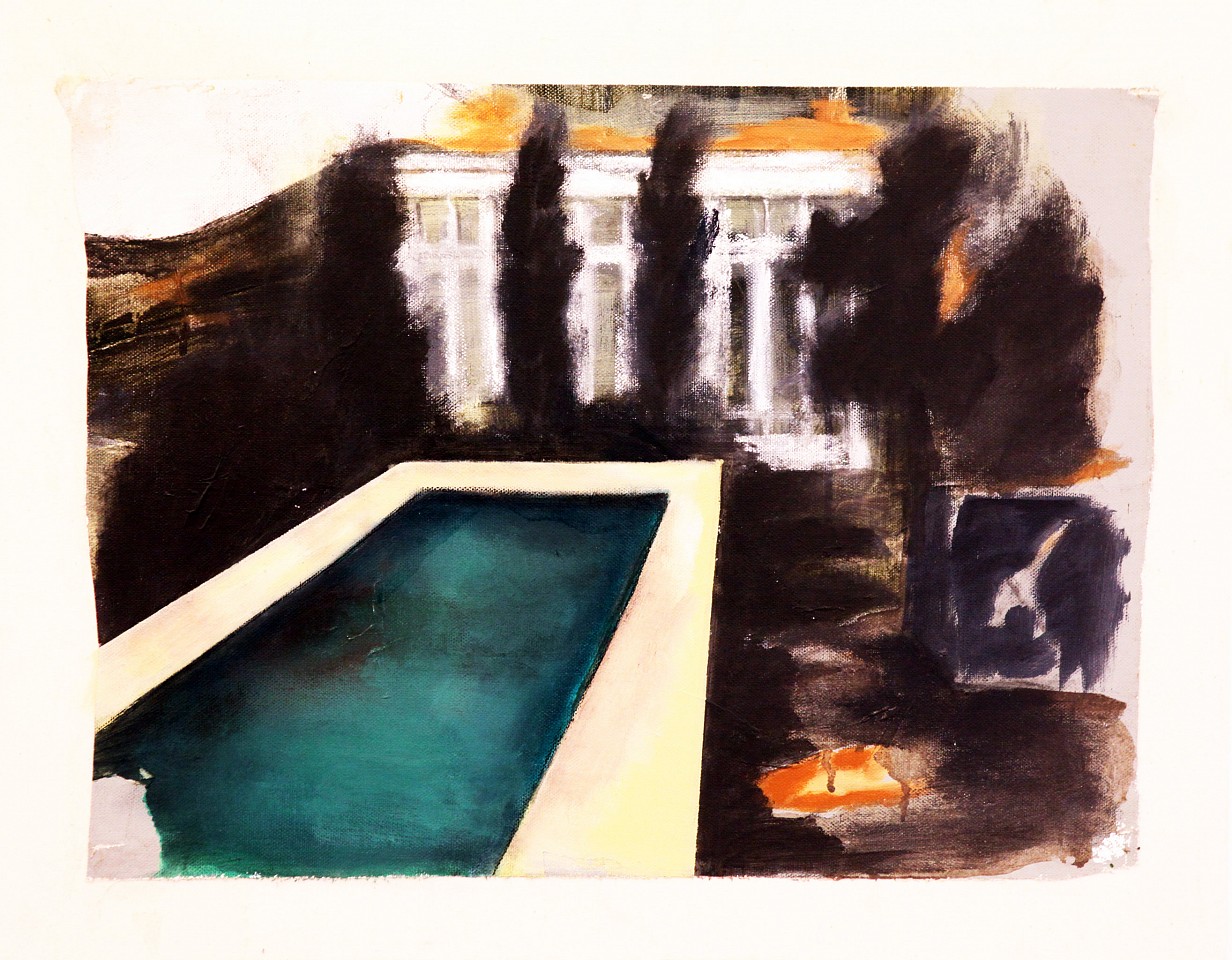

Tamara Al Samerraei

Untitled 01, 2017

Acrylic paint on canvas

TAS0001

Tamara Al Samerraei

Untitled 03, 2017

Acrylic paint on canvas

TAS0003

Tamara Al Samerraei

Untitled 2, 2017

Acrylic paint on canvas

TAS0002

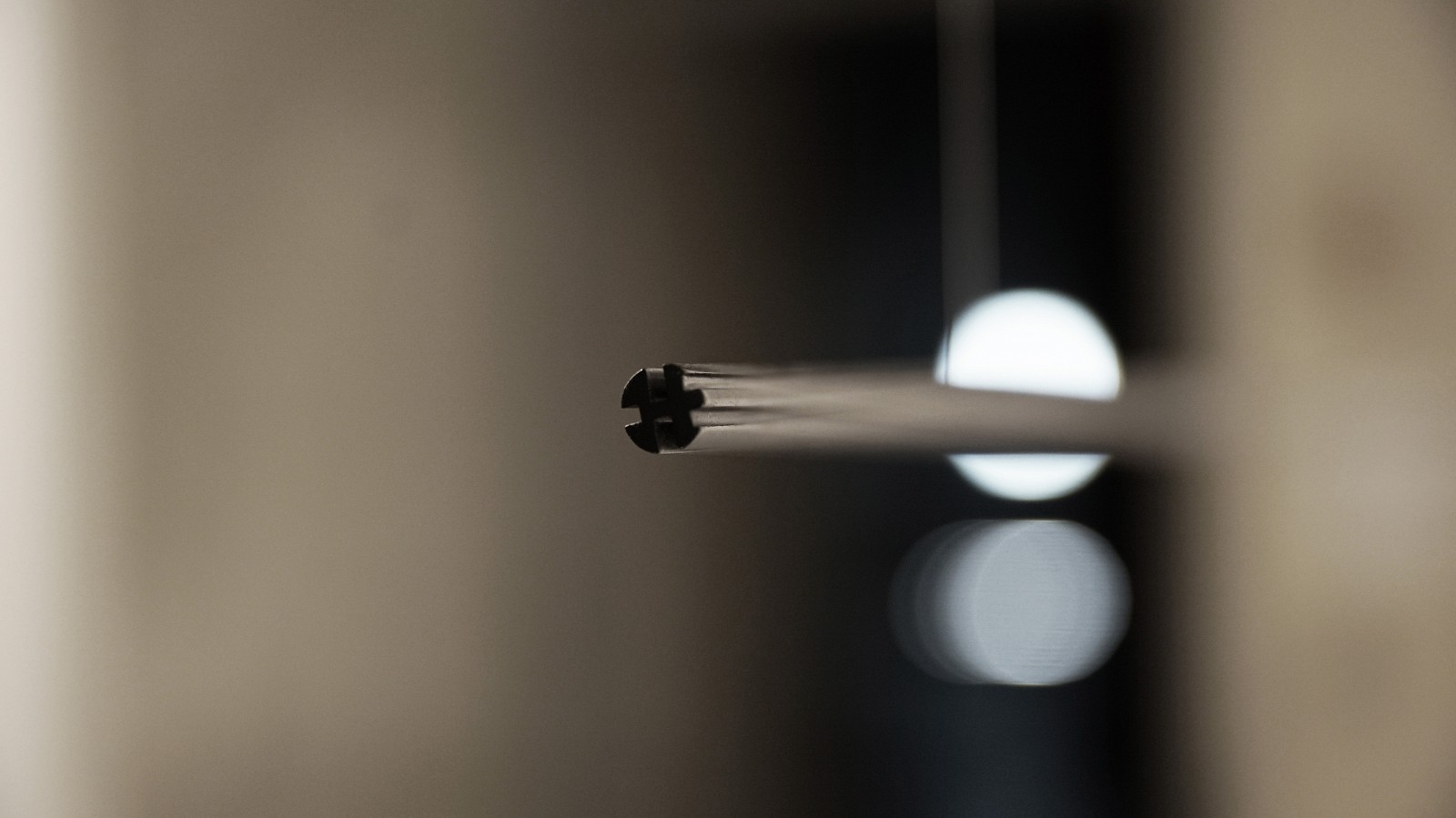

Reem Al-Nasser

Jasmine Bullets, 2018

Dried Arabian Jasmines

Edition of 3

RAN0007

Moath Alofi

Adah from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

218 x 145 cm

MAO0085

Moath Alofi

Enoch from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

145 x 218 cm

MAO0087

Moath Alofi

Jabal and Jubal from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

73 x 109.5 cm

MAO0088

Moath Alofi

Japheth from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

145 x 218 cm

MAO0084

Moath Alofi

Lamech from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

109.5 x 73 cm

MAO0089

Moath Alofi

Mehujael from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

145 x 218 cm

MAO0086

Moath Alofi

Naamah from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

MAO0090

Moath Alofi

Nod from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

MAO0093

Moath Alofi

Tubal-Cain from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

MAO0091

Moath Alofi

Zillah from the People of Pangaea series, 2018

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm

MAO0092

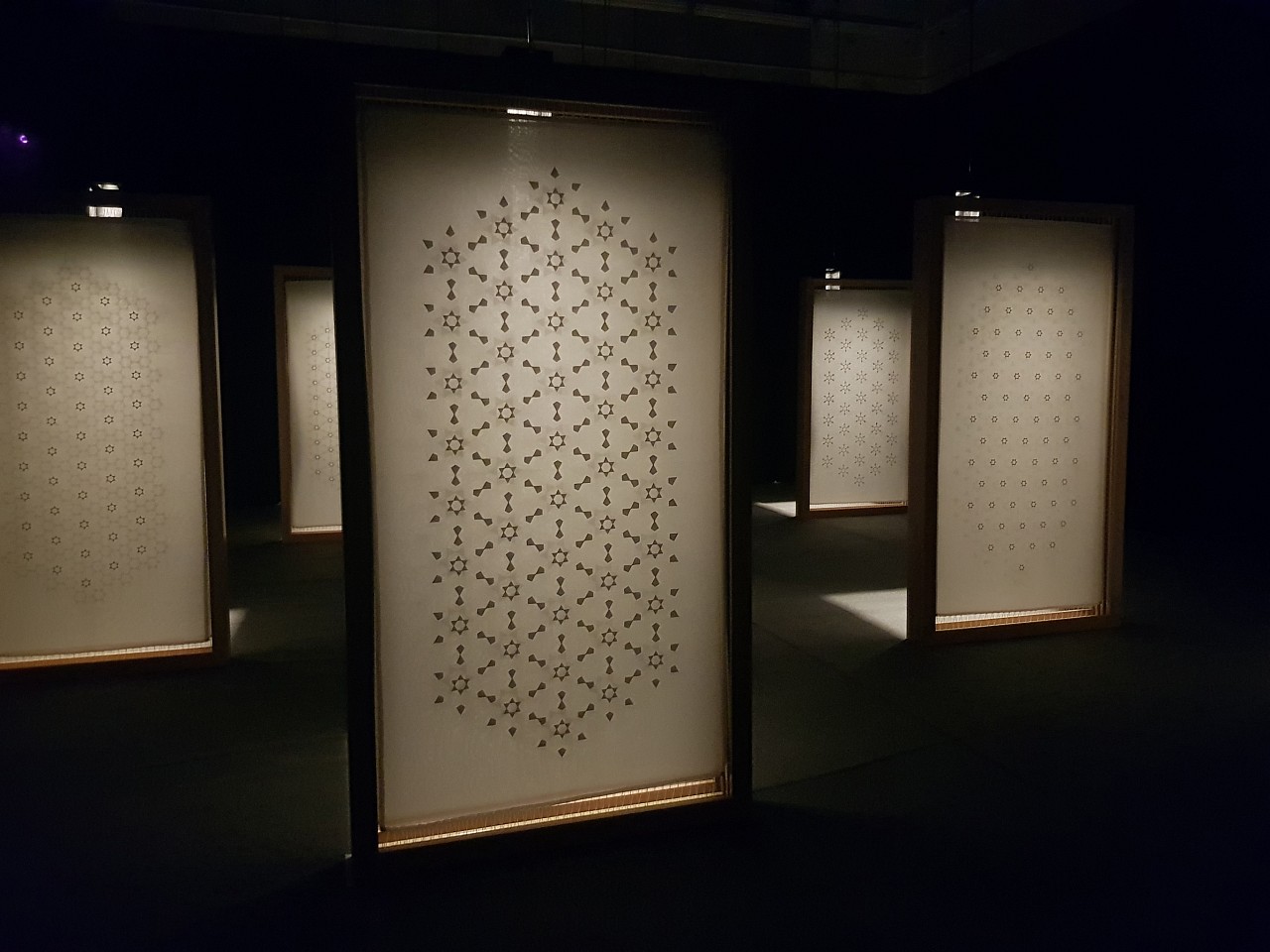

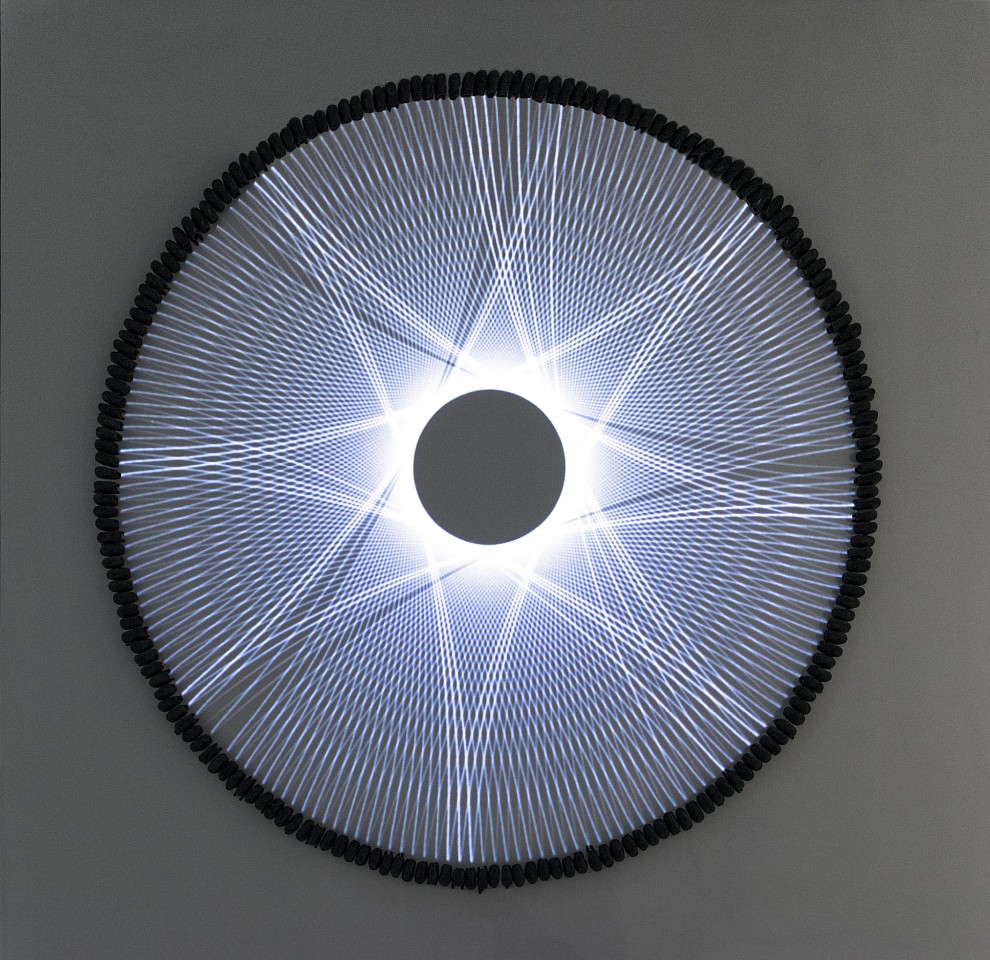

Dana Awartani

Listen to My Words, 2018

Multi media (7 panels of hand embroidery on silk and sound installation)

DAN0141

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Take Me Somewhere Nice series, 2018

Video installation

AYD0682

Aya Haidar

Boatloads, from the Soleless series, 2018

Embroidery on shoe soles

AYH0087

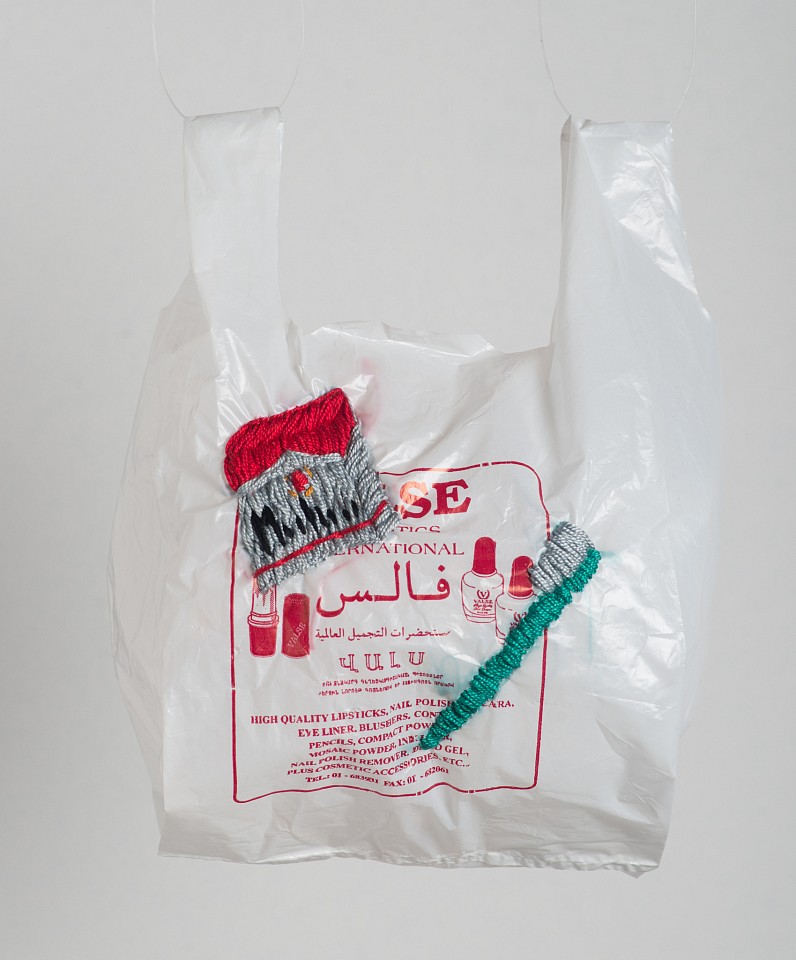

Aya Haidar

Cigarettes, Toothbrush, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0097

Aya Haidar

Coffee pot, Bread, Toothbrush, Bottle of water, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0096

Aya Haidar

Falafel, Coffee pot, Pistachio nuts, from of the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0092

Aya Haidar

He walked from Turkey to Germany carrying his 3 kids on his back from the Soleless series, 2018

Embroidery on shoe soles

AYH0085

Aya Haidar

Hijab, Medication, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0100

Aya Haidar

In Zaatari Camp they marry 13 year old girls and divorce them 2 months later, from the Soleless series, 2018

Embroidery on shoe soles

AYH0089

Aya Haidar

Inhaler, Pen, Purse, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0105

Aya Haidar

Jewellery, Socks, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0103

Aya Haidar

Nappy, Nido, Glasses, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0099

Aya Haidar

Patrol, from the Soleless series, 2018

Embroidery on shoe soles

AYH0086

Aya Haidar

Period pad, sweets, Housekey, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0095

Aya Haidar

Pills, Cigarettes, Needle and thread, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0102

Aya Haidar

Stay low, from the Soleless series, 2018

Embroidery on shoe soles

AYH0090

Aya Haidar

Swiss Army Knife, iPhone, Misbaha, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0098

Aya Haidar

T-Shirts, Shorts, Glasses, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0101

Aya Haidar

They made her choose which of her children to kill first, from the Soleless series, 2018

Embroidery on shoe soles

AYH0088

Aya Haidar

Tray of Warak Enab, Kaak, Lighter, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0093

Aya Haidar

Underwear, Tweezers, Razor, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0091

Aya Haidar

Watch, Earphones, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0104

Aya Haidar

Wedding photo, Phone Charger, from the Kiass series, 2018

Embroidery on plastic bag

AYH0094

Aya Haidar

What I Left Behind, 2018

Mixed media (cotton thread embroidered on patched fabric)

AYH0106

Mohamed Monaiseer

Toy Soldier, 2015-2018

Acrylic on cotton fabric

MM0019

Maha Nasrallah

Transference, 2018

Clay, earthenware

MN0001

Larissa Sansour

29 ° 32' 26" N/34 ° 56' 50" E (Red Sea), from Archaeology in Absentia series, 2016

Bronze and steel

20 cm

Larissa Sansour

31 ° 47' 9" N/35 ° 13' 58" E (Jerusalem), from Archaeology in Absentia serie, 2016

Bronze and steel

20 cm

Larissa Sansour

31 ° 51' 05" N/35 ° 28' 44" E (Jericho), from Archaeology in Absentia series, 2016

Bronze and steel

20 cm

Larissa Sansour

32 ° 3' 5" N/34 ° 44' 54" E (Jaffa), from Archaeology in Absentia series, 2016

20 cm

Larissa Sansour

32 ° 47' 11" N/35 ° 32' 39" E (Tiberias), from Archaeology in Absentia series, 2016

Bronze and steel

20 cm

Larissa Sansour

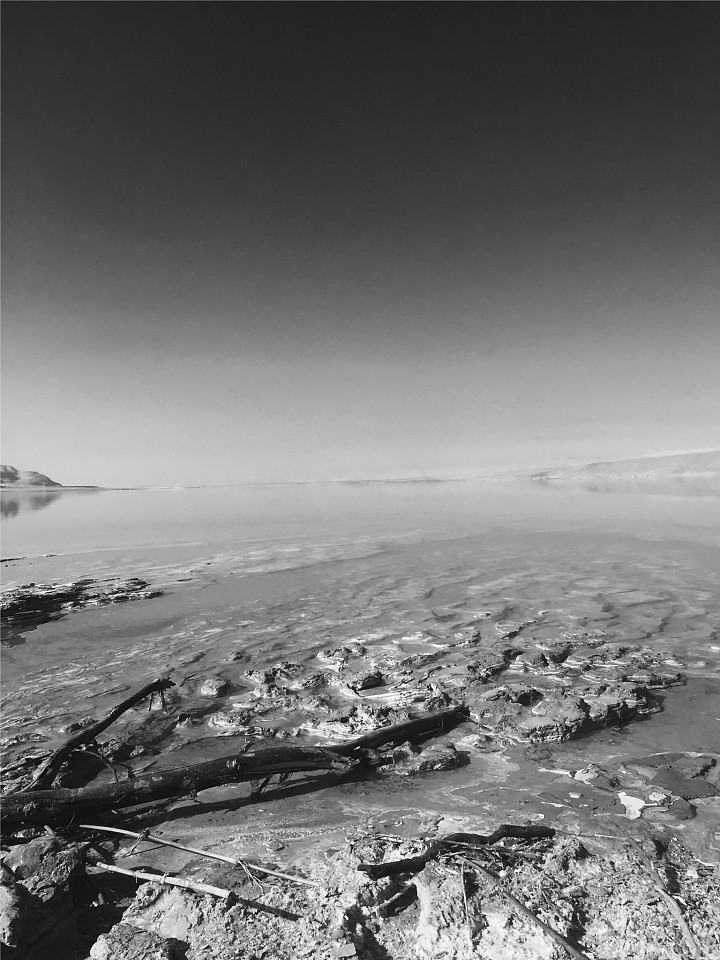

Dead Sea 1, from Archaeology in Absentia series, 2016

Photographs printed on Hahnemuehle Fine Art paper 325g (Baryta paper)

LAS0015

Larissa Sansour

Haifa 1, from Archaeology in Absentia series, 2016

Photographs printed on Hahnemuehle Fine Art paper 325g (Baryta paper)

LAS0016

Larissa Sansour

In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain, 2016

Film

LAS0017

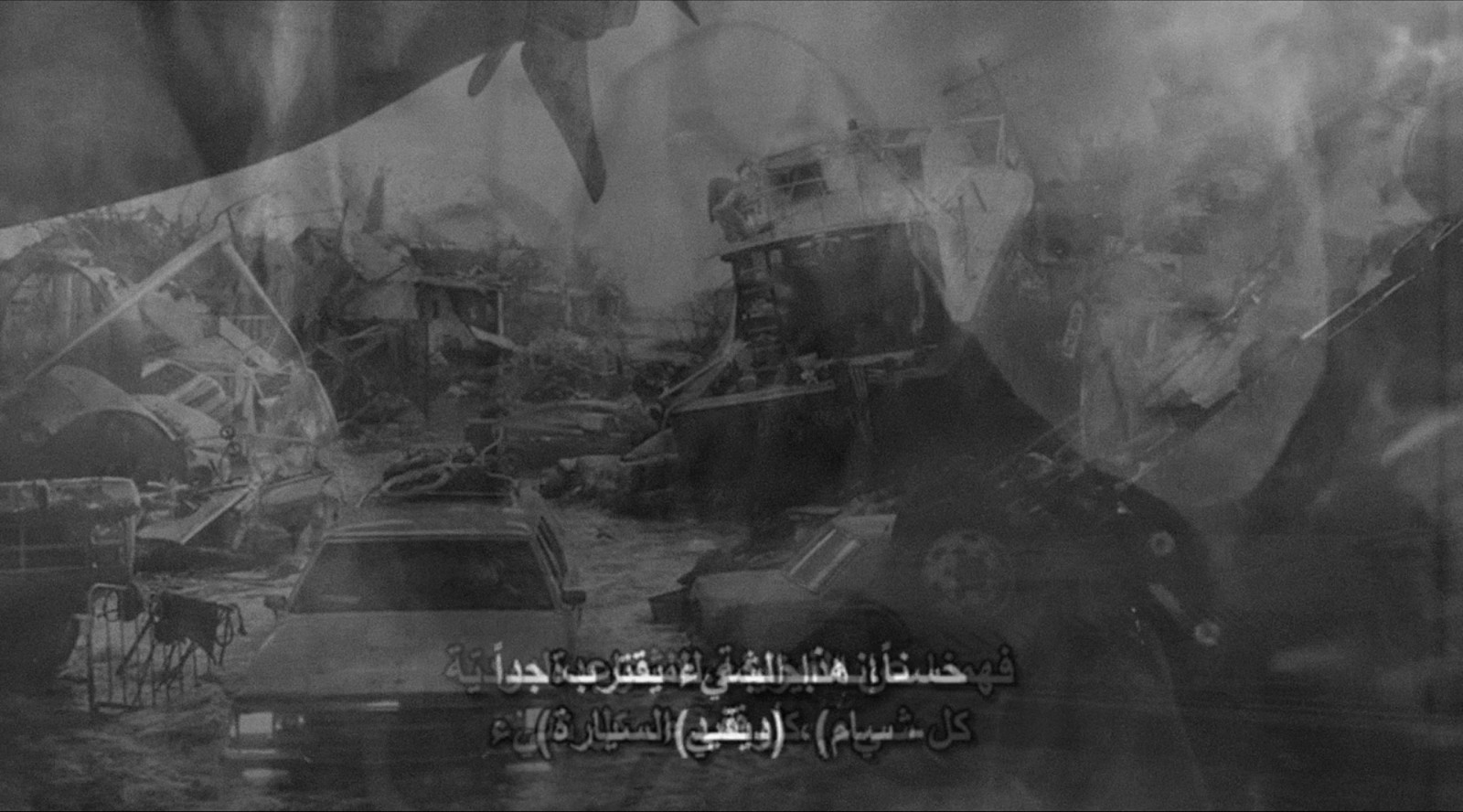

Wael Shawky

Al Araba Al Madfuna III, 2015

B&W film, sound, subtitles

WS0001

Muhannad Shono

Al-Ashirah, 2018

Mixed media installation (200 polymer clay sculptures + video projection & musical composition)

MSH0066

Muhannad Shono

Gal, from the Heads of the Tribe series, 2018

Polymer clay sculpture and fabric

MSH0068

Muhannad Shono

Kal, from the Heads of the Tribe series, 2018

Polymer clay sculpture and paper

MSH0069

Muhannad Shono

Tal, from the Heads of the Tribe series, 2018

Polymer clay sculpture and fabric

MSH0067

Muhannad Shono

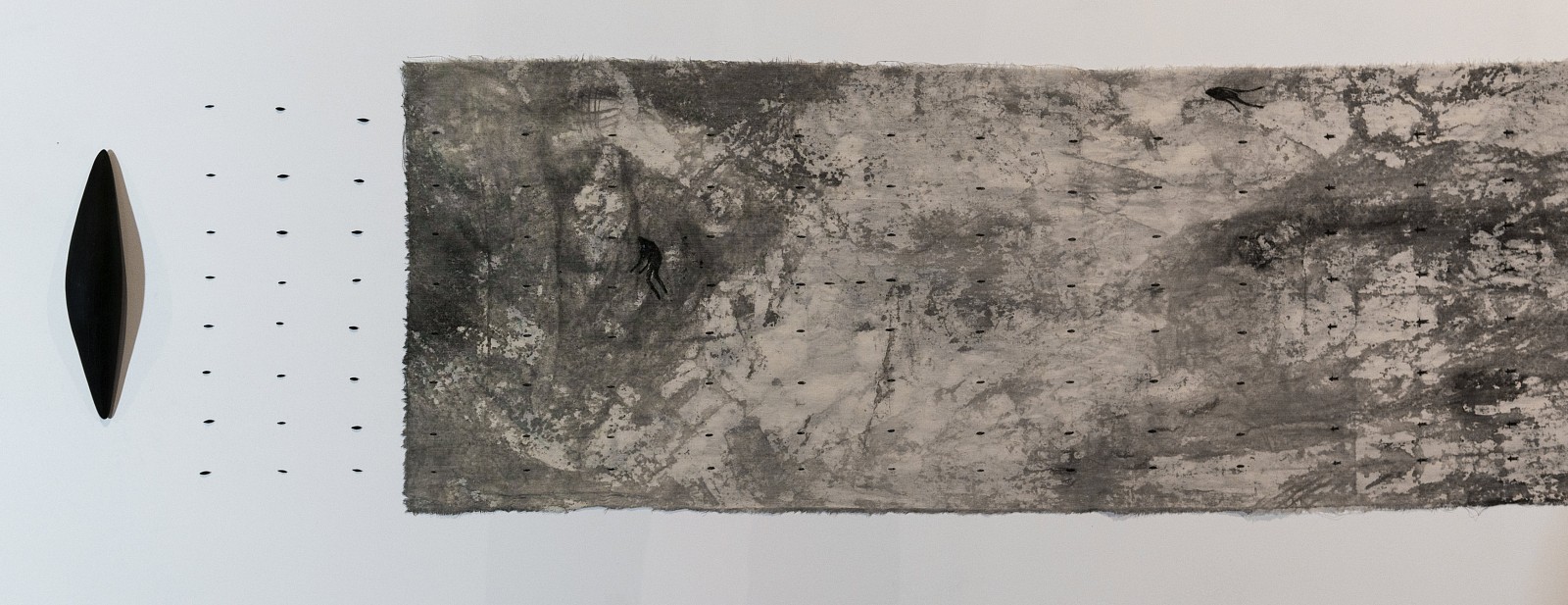

The Book of Al, 2018

Ink illustrations on stitched and stained hemp fabric + polymer clay sculptures

MSH0070

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

A Greater Chain of Being

Personal memory, fantasy and collective consciousness come in and out of focus in ARasoul’s practice. "In this life one meets faces and features of people. Some are full of life, some are lost or confused and others are like the walking dead.” To the artist, all are linked in continuous, ad infinitum, progressive lines which, projected into time, renders the future a decodable enigma. Not anymore.

In this age of hyper connectivity and interdependency, both emerging from and shaping our global societies, these continuous lines are evolving into networks – fluid, simultaneous, indefinite, pervasive. Being on-line is gaining time from other activities, with the new generation living increasingly in the public realm, yet creating new forms of solitary confinement. Human beings are evolving into humanoids. When will they seize being human? How will we differentiate?

Soulless carcasses yet connected.

Sara Abdu’s current work is based on the repetitive movement of her hand drawing a shape she has always incorporated in her previous work. The shape is meaningless beyond being the output of the artist's unconscious hand movement while immersed in her inner world. In its entirety, the work is a testament to the journey the artist experiences in executing her drawing. The stages she passes through are documented in the irregularity of the shape, its imprint on the paper and the shade of the ink.

This is a personal journey the artist embarked on. The source for the project was a prayer mat she inherited from a dear uncle who passed away. This mat has been a companion on multiple trips and bore witness to a lifetime of memories the artist is eager to be the gate keeper even if not the code breaker. She translates the years of ownership into the size her drawing will end up be, as if drawing a parallel timeline of replicated experiences.

Can transcendence through repetition allow her to reach that inner state of true self, abstracted from external intrusions? Can reaching this state build a thrusting energy to allow her inner self to shine pure and absolute?

This digital installation sets up a configuration of screens into a 3-Dimensional box, onto which 3 distinct narratives are diffused. The work sets to blur the lines between factual footage and fiction in a bid to raise questions around our absorption of information through channels that we are exposed to on a daily basis. The use of visual material, audio, space, colour and light all contribute to the experiential dynamic of this body of work.

The 3 films will be presented in a sort of factual gradient, from factually correct, to partly fictional and finally a cinematic montage of images interlaced with presumed narratives.

The first segment, titled Sofia, sets the scene of a contemporary TV program around recent news regarding a robot called Sofia who was granted Saudi citizenship. This footage is then juxtaposed with real life footage of a stateless people.

The second segment, titled The Turtle, looks back at 1980’s footage of a 100 year old turtle being released into open waters. The incredibly moving scene is later juxtaposed with the ruthless slaughter of an elderly turtle by Saudi men in a bit to eat it. The turtle moves across the screens, whimsically floating through space.

The third and final segment, titled Death to TV, Long Live the Image, fills the whole installation’s screens in its entirety. It starts with a black screen with but the sound of a fire burning. The screen later elucidates a burning TV in a deserted location. A man stands before the camera, with a TV in place of his head, pointing a gun to it. As he sets off the gun, birds fly free. What follows is a sequence of disjointed footage which pans out until it stops before a mirror reflecting back the camera as it zooms into the lens.

This body of work pivots on notions of perspective, both literal and metaphorical, where the fragmentation of the image echoes a wider statement about the diffusion and reliability of news and information we have grown so reliant on.

A thin metallic black rod, carved using a calligraphic rendering based on the Kufi script, will exhibit the term Amma Baad.

The expression is an Arabic term used typically in official letters when salutations and respect are paid and the subject of the communication is yet to be revealed. It is a moment in space and time where and when what preceded sank in nothingness and what follows is infinite.

Time, being considered as the fourth dimension, interlaces this notion within the sculptural piece where it becomes part of time within itself and can only be approached through language.

Amma Baad is a promise. It is hope, fear, expectation, and trepidation. It is silence, it is noise. It is nothing and everything. It is waiting.

Hotel Particulier

Tamara Al Samerraei’s paintings are based on photographs from both her personal archive and the public domain. Film stills, digital images and other found, stolen or borrowed visual materials are brought together to extend contemplation of familiar scenes.

‘Val de Pome’ (2017) is a series of paintings that draw on faded snapshots from the artist’s archive, depicting people on summer vacation by the pool. Although the original photos are representative of the glamour, luxury and sensuality often associated with such picturesque moments, they are filtered through the artist’s dark, recurring dreams that have informed her palette. Water is not rendered as reflective but rather an opaque and viscous substance, which the figures dip into, blithely unaware of your presence.

Hotel Particulier

Tamara Al Samerraei’s paintings are based on photographs from both her personal archive and the public domain. Film stills, digital images and other found, stolen or borrowed visual materials are brought together to extend contemplation of familiar scenes.

‘Val de Pome’ (2017) is a series of paintings that draw on faded snapshots from the artist’s archive, depicting people on summer vacation by the pool. Although the original photos are representative of the glamour, luxury and sensuality often associated with such picturesque moments, they are filtered through the artist’s dark, recurring dreams that have informed her palette. Water is not rendered as reflective but rather an opaque and viscous substance, which the figures dip into, blithely unaware of your presence.

Hotel Particulier

Tamara Al Samerraei’s paintings are based on photographs from both her personal archive and the public domain. Film stills, digital images and other found, stolen or borrowed visual materials are brought together to extend contemplation of familiar scenes.

‘Val de Pome’ (2017) is a series of paintings that draw on faded snapshots from the artist’s archive, depicting people on summer vacation by the pool. Although the original photos are representative of the glamour, luxury and sensuality often associated with such picturesque moments, they are filtered through the artist’s dark, recurring dreams that have informed her palette. Water is not rendered as reflective but rather an opaque and viscous substance, which the figures dip into, blithely unaware of your presence.

Reem Al Naser’s project began as an exploration of society’s customs and rituals, their intransigence and their adaptation to the change that affects their communities.

In this installation, AlNasser recreates the ornaments a bride from the south of Saudi Arabia (Jizan) is adorned with the day of her marriage. These flower adornments are made from the Arabian Jasmine, primarily weaved and designed by Yemenis. In recent times, these arrangements came to be called Full Rassass (Jasmine bullet).

The artist is commenting on the concept of glorification. Like these jasmine buds plucked early, fading and withering before they are given a chance to blossom, so is the fate of many young women. Escaping the yoke of a strict and severe upbringing, many find themselves caught in a transfer of authority from the parents to the husband.

The juxtaposition of Full and Rassass is one of dark reality: life and death, celebration and mourning, glorification and vilification. These are themes of existence; however, the issue arises when one aspect predominates alternative realities.

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

A series of photographs taken from the air tread the line between reality and fiction. The scapes, be it landscapes, desertscapes, even moonscapes, offer a multiplicity of possibilities as to where their locality could be or where their origins stem from. Raising more questions than diffusing answers, these images present wonders in no uncertain terms.

The photographs of these anomalous formations, the oldest of which believed to be 9,000 years old, are aerial views shot over the vicinity of the holy city of Medina. The patterns created across the land are recognised as either gates, kites or keys, identified by pilots in the early 1920’s. They each occupy vast areas of land through a very ordered and distinct placement of the volcanic rock.

The artist’s selection of this body of work to reflect on the exhibition concept questions history on the value of its past in its relationship with the present. Being born and raised in Medina, the artist does not recall any mentioning of these mysterious structures; and yet, they have been known of since 1920s. Would the knowledge of their existence have changed his understanding of the present? Would it have impacted his interpretation of the past?

Dana Awartani presents an immersive installation that combines hand embroidered silk panels with moving sounds of women reciting poetry. Throughout history, the woman’s role has always been underrepresented within art, politics and science. When referencing Arab and Islamic poetry and literature from the region, names such as Rumi, Hafez and Ibn Arabi most often spring to mind. This body of work sets to lift the veil on a whole cast of radical female poets that range from the pre Islamic times up to the 12th century. The poems and poetesses hail from a wide range of cultures within the Arab world and explore the themes of love, lust and longing.

The presence of geometric layered panels throughout this work references the ‘Jali’ screen, which is characteristic of the Islamic tradition and more specifically in this piece, Mughal India, and they were typically used to shield women from the male gaze. In this case, the artist has reinvented these screens by using embroidery in collaboration with craftsmen in India, and has chosen a specific stitch called ‘Aari’ which derived from the Mughal period. Awartani was more specifically inspired by a figure named Nourjehan who was the wife of a Mughal Emperor and she partook a leading yet hidden role in governing the state while being forced to sit behind a Jali screen, whispering commands into her husband’s ear.

The work juxtaposes theory and execution, as the installation is one that evokes serenity and contemplation interjected with radical words within the space.

The recitation of the poetry is done in its original language of Arabic, using the voices of Sara Abdu, Fatima Al Banawi, Najla Al Bassam, Ahd Kamel and Zahar Al Sayed - modern day Saudi women who embody the spirits of these forgotten poetesses, strong, empowered and inspirational.

Without light, there is no vision. But to what degree is vision a reflection of reality?

Scientists and philosophers have extensively researched the relationship between light, vision and reality. While we know that different areas of the brain deal with colour, form, motion and texture, our visual system remains too limited to tackle all of the information our eyes take in. And so our minds take shortcuts.

Moreover, since light takes time to reach our eyes, then in reality, the world we perceive is somewhat in the past. And so our minds make predictions in order to perceive the present.

Therefore, how can what one experiences be a direct representation of his/her surroundings? How can reality be real?

Ayman Yossri’s installation of 8 screens consists of compilations of stills from a plethora of movies, documentaries, news report, etc., recorded and played at very high speed. The visual outcome is akin to seeing moving shades of light.

Behind the light of every screen, Ayman Yossri is visually narrating moments, events, stories that have shaped his life, that of others, the region and beyond. The work builds itself into a kind of artist manifesto, broadcasted to the wider public but revealed to none.

This current body of work from the Soleless series has been produced in response to a 3 month artist residency program, working directly in reintegrating newly arrived Syrian refugee communities into the UK.

From this experience, first-hand accounts and interpersonal exchanges over the perilous passages ventured, stories of separation, loss and every day realities are intimately embroidered on the underside of worn shoes.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work from the Soleless series has been produced in response to a 3 month artist residency program, working directly in reintegrating newly arrived Syrian refugee communities into the UK.

From this experience, first-hand accounts and interpersonal exchanges over the perilous passages ventured, stories of separation, loss and every day realities are intimately embroidered on the underside of worn shoes.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work from the Soleless series has been produced in response to a 3 month artist residency program, working directly in reintegrating newly arrived Syrian refugee communities into the UK.

From this experience, first-hand accounts and interpersonal exchanges over the perilous passages ventured, stories of separation, loss and every day realities are intimately embroidered on the underside of worn shoes.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work from the Soleless series has been produced in response to a 3 month artist residency program, working directly in reintegrating newly arrived Syrian refugee communities into the UK.

From this experience, first-hand accounts and interpersonal exchanges over the perilous passages ventured, stories of separation, loss and every day realities are intimately embroidered on the underside of worn shoes.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work from the Soleless series has been produced in response to a 3 month artist residency program, working directly in reintegrating newly arrived Syrian refugee communities into the UK.

From this experience, first-hand accounts and interpersonal exchanges over the perilous passages ventured, stories of separation, loss and every day realities are intimately embroidered on the underside of worn shoes.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work from the Soleless series has been produced in response to a 3 month artist residency program, working directly in reintegrating newly arrived Syrian refugee communities into the UK.

From this experience, first-hand accounts and interpersonal exchanges over the perilous passages ventured, stories of separation, loss and every day realities are intimately embroidered on the underside of worn shoes.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This current body of work grew from the curiosity of identifying what people take when forced to leave their home? During a 3 month residency program, working to reintegrate Syrian refugee communities into the UK, first-hand accounts were shared and this precise question explored. With the vast majority of refugees fleeing with but the clothes on their back and a plastic bag containing ‘essentials’, this notion forms the central theme around this work. Plastic bags are commonly used, over an otherwise more practical suitcase, for fear of drawing attention to their fleeing which would be interdicted by the government forces.

From period pads to cigarettes, needle and thread to a falafel maker, a Rakweh (coffee pot) to heart medication; these salvaged items span the sentimental, to the practical, essential and desired, each carefully embroidered onto their respective owner’s bag.

This patched quilt frames 6 panels, each carefully embroidered around the Narratives shared by refugees about the things they most regretfully left behind in their native Syria. A generational and geographical cross section, looking back at the homeland they left with the adored individuals and valued things they could not save with them. A young Layal innocently describing how she left her toys under her bed to keep them safe until she returns; Naim who recently graduated with a biochemistry degree, leaving his certificate behind; Rafic the family dog who couldn’t be taken; to leaving one’s elderly parents because they refused to leave their homeland; Huda’s family photo albums spanning generations; to Mohannad’s ID papers making him feel like he has lost his identity with nowhere to go and no way to prove where he has come from. These inter personal revelations are carefully hand embroidered onto collected items of clothing where the fabric itself bears the weight of the journey as much as the story itself. The patched fabric used to create the borders around each panel has been locally sourced in the UK where this group of refugees has now been relocated. This fabric is used to upholster and drape the furnishings of their new homes.

About the idea that been implanted in the infant's brains causing the feeling of pride towards this tool; the tool repeatedly created to cause destruction, to harm people, and to loot them. Then it was nothing but a cover to legalise the so-called kind invasion, and to establish colonialism with widespread acceptance, depriving them of resistance against the coloniser. Likely, the highest achievement is understanding what goes inside the infant’s child to follow the counternarrative. The least could be the denial of murder.

This pain isn’t caused only by imperialism but also accepted by the governing bureaucratic elite. It’s a language perfected by the mute that is beyond self-realisation. It aims to scatter popular will and destroy principles. Consequently, this leads to confusion in the choices made to be afraid and to submit completely.

Who are these unknown individuals and numbers? They are but walls and shields that continue to decrease and raise the bargaining limits. It is a trade in construction and destruction; a skill to manufacture the disease to sell the medicine.

… "the transference, which, whether affectionate or hostile, seemed in every case to constitute the greatest threat to the treatment, becomes its best tool"

Freud, S.

Today, 27 years after the Lebanese war stopped, many unresolved issues remain present. I am one of the lucky survivors. However I carry, buried deep inside of me, a feeling of loss.

In the same way that the death of a close friend’s parent can trigger one’s tears and grief over one’s own personal loss, by transference, the Syrian conflict has unleashed my feelings and my desire to express my frustration with the Lebanese war, the Syrian war, and wars in general.

I worked on the “qobqab”, the Syrian sabot, as a symbol to represent the absence, the loss. The loss of a culture, of an artisan’s society, of tradition, of a human being, of life.

Traditionally, these slippers are exposed by being hung on shop walls in the souks of Damascus or Aleppo. I chose that same way to exhibit the 144 clay “qobqab” to form a “memorial wall”, reminding us that wars never end with winners but only with victims.

Archaeology in Absentia is a sculptural installation of fifteen 20cm bronze munition replicas modelled on a small Cold War Russian nuclear bomb. Engraved on a disc inside each capsule are the coordinates, longitude and latitude, to a deposit of hand-painted porcelain plates with folkloric patterns buried in Palestine. With the porcelain itself absent from the installation, the bomb shells and the references they hold represent the archaeological artefacts in absentia.

The coordinates of each porcelain deposit were established during a real-life entombment performance in Israel/Palestine. Fifteen deposits were buried strategically across the region, in collaboration with local art institutions - in places such as Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Haifa, Nazareth, Jaffa and the Dead Sea. A black and white photo series document the locations of each deposit. Carrying the iconic keffiyeh pattern, these plates were deposited for future archaeologists to excavate. Once unearthed, they will interfere with current versions of history and in effect cause a historical intervention.

Archaeology in Absentia is a sculptural installation of fifteen 20cm bronze munition replicas modelled on a small Cold War Russian nuclear bomb. Engraved on a disc inside each capsule are the coordinates, longitude and latitude, to a deposit of hand-painted porcelain plates with folkloric patterns buried in Palestine. With the porcelain itself absent from the installation, the bomb shells and the references they hold represent the archaeological artefacts in absentia.

The coordinates of each porcelain deposit were established during a real-life entombment performance in Israel/Palestine. Fifteen deposits were buried strategically across the region, in collaboration with local art institutions - in places such as Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Haifa, Nazareth, Jaffa and the Dead Sea. A black and white photo series document the locations of each deposit. Carrying the iconic keffiyeh pattern, these plates were deposited for future archaeologists to excavate. Once unearthed, they will interfere with current versions of history and in effect cause a historical intervention.

Archaeology in Absentia is a sculptural installation of fifteen 20cm bronze munition replicas modelled on a small Cold War Russian nuclear bomb. Engraved on a disc inside each capsule are the coordinates, longitude and latitude, to a deposit of hand-painted porcelain plates with folkloric patterns buried in Palestine. With the porcelain itself absent from the installation, the bomb shells and the references they hold represent the archaeological artefacts in absentia.

The coordinates of each porcelain deposit were established during a real-life entombment performance in Israel/Palestine. Fifteen deposits were buried strategically across the region, in collaboration with local art institutions - in places such as Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Haifa, Nazareth, Jaffa and the Dead Sea. A black and white photo series document the locations of each deposit. Carrying the iconic keffiyeh pattern, these plates were deposited for future archaeologists to excavate. Once unearthed, they will interfere with current versions of history and in effect cause a historical intervention.

Archaeology in Absentia is a sculptural installation of fifteen 20cm bronze munition replicas modelled on a small Cold War Russian nuclear bomb. Engraved on a disc inside each capsule are the coordinates, longitude and latitude, to a deposit of hand-painted porcelain plates with folkloric patterns buried in Palestine. With the porcelain itself absent from the installation, the bomb shells and the references they hold represent the archaeological artefacts in absentia.

The coordinates of each porcelain deposit were established during a real-life entombment performance in Israel/Palestine. Fifteen deposits were buried strategically across the region, in collaboration with local art institutions - in places such as Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Haifa, Nazareth, Jaffa and the Dead Sea. A black and white photo series document the locations of each deposit. Carrying the iconic keffiyeh pattern, these plates were deposited for future archaeologists to excavate. Once unearthed, they will interfere with current versions of history and in effect cause a historical intervention.

Archaeology in Absentia is a sculptural installation of fifteen 20cm bronze munition replicas modelled on a small Cold War Russian nuclear bomb. Engraved on a disc inside each capsule are the coordinates, longitude and latitude, to a deposit of hand-painted porcelain plates with folkloric patterns buried in Palestine. With the porcelain itself absent from the installation, the bomb shells and the references they hold represent the archaeological artefacts in absentia.

The coordinates of each porcelain deposit were established during a real-life entombment performance in Israel/Palestine. Fifteen deposits were buried strategically across the region, in collaboration with local art institutions - in places such as Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Haifa, Nazareth, Jaffa and the Dead Sea. A black and white photo series document the locations of each deposit. Carrying the iconic keffiyeh pattern, these plates were deposited for future archaeologists to excavate. Once unearthed, they will interfere with current versions of history and in effect cause a historical intervention.

In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain resides in the cross-section between sci-fi, archaeology and politics. Combining live motion and CGI, the film explores the role of myth for history, fact and national identity.

A narrative resistance group makes underground deposits of elaborate porcelain - suggested to belong to an entirely fictional civilization. Their aim is to influence history and support future claims to their vanishing lands. Once unearthed, this tableware will prove the existence of this counterfeit people. By implementing a myth of its own, their work becomes a historical intervention - de facto creating a nation.

The film takes the form of a fictional video essay. A voice-over based on an interview between a psychiatrist and the female leader of the narrative resistance group reveals the philosophy and ideas behind the group's actions. The leader's thoughts on myth and fiction as constitutive for fact, history and documentary translate into poetic and science fiction-based visuals.

As the film progresses, the narrative and visuals alternate between the theoretical and the personal. The resistance leader's deceased twin sister makes a crucial appearance as the story takes the viewer deeper and deeper into the resistance leader's subconscious.

Al Arab Al Madfuna III

Al Araba Al Madfuna (2012 - 2015) is a film trilogy based on the artist's personal visit to the village Al Araba Al Madfuna (hence the title of the film) in the Southern part of Egypt more than ten years ago, where he discovered that people in the village would rely on supernatural powers of the shaman to guide them in digging treasures buried by their ancestors underground. This process would takes years and generations and he was fascinated by the idea of people relying on the metaphysical to search for physical materials.

The first two films were filmed in the village called Al Araba Al Madfuna, and the third inside a temple in Egypt. Wael used children as actors in the films, continuing with the same idea of alienation and estrangement as with the marionettes in his Cabaret Crusades trilogy, and in addition, the children are "genderless" as are the marionettes.

In Al Araba Al Madfuna, Wael blends intales from Mohamed Mostagab's book Dairout al Sharif with his personal visit to the village, which are narrated by the children dubbed in classical Arabic in an adult's voice. This creates several layers of alienation – children acting as adults and speaking in adult voices, and the narration of imaginary tales from ancient times which do not correspond to the setting nor the events happening in the film. In the final instalment of Al Araba Al Madfuna, the artist produced the film in negative, which further highlights the reversal of roles and narratives.

The characters are played by children in adult dress, with their voices dubbed by adults. By using children to enact the stories with adult voices and dress, Shawky leaves an open-ended interpretation to the work.

The film premiered at the Serpentine Gallery, London in 2013.

In our species’ not so distant future, we have lost control of our stories.

Our world is now governed by tribal stories in their political, extremist, nationalistic, and sectarian genres. In this future, stories are diagnosed as a disease of the mind. An infection we must be quarantined away from.

In a bid to save itself from its own stories, our species sends forth its seeds into the stars in a mission to populate a new planet far away from the narratives of our own.

Carried on board a mother ship, whose mission is to sow a distant soil with a new, story-less, human tribe.

Each seed is a material that acts as a new technological skin, encasing the human life that grows within it.

A skin that is the final layer of our technological evolution designed to imprison the human instinct to tell stories.

There is no thirst inside this skin, no hunger, no illness or pain. The individual within is rendered self-sufficient, self-reliant and in no need of the collective tribe. The skin, through its obscuring helmet, prevents all human emotions and forms of expression from being transmitted out.

Any attempt to tell a story is caught by algorithms that censor, filter out, and mute through this wearable firewall.

But within this new tribe, the need to share the stories they each carried in isolation only grows stronger.

Until the first helmet is removed and a story is told.

Then the second helmet is removed and a story is first heard.

And when all the helmets are removed, the stories spread through the tribe until there is no one left to tell them, or for stories to be heard.

Except for one, ‘Al Al-Ashirah’, the one who placed back his helmet and returned to our planet, bringing with him the stories of his tribe.

In our species’ not so distant future, we have lost control of our stories.

Our world is now governed by tribal stories in their political, extremist, nationalistic, and sectarian genres. In this future, stories are diagnosed as a disease of the mind. An infection we must be quarantined away from.

In a bid to save itself from its own stories, our species sends forth its seeds into the stars in a mission to populate a new planet far away from the narratives of our own.

Carried on board a mother ship, whose mission is to sow a distant soil with a new, story-less, human tribe.

Each seed is a material that acts as a new technological skin, encasing the human life that grows within it.

A skin that is the final layer of our technological evolution designed to imprison the human instinct to tell stories.

There is no thirst inside this skin, no hunger, no illness or pain. The individual within is rendered self-sufficient, self-reliant and in no need of the collective tribe. The skin, through its obscuring helmet, prevents all human emotions and forms of expression from being transmitted out.

Any attempt to tell a story is caught by algorithms that censor, filter out, and mute through this wearable firewall.

But within this new tribe, the need to share the stories they each carried in isolation only grows stronger.

Until the first helmet is removed and a story is told.

Then the second helmet is removed and a story is first heard.

And when all the helmets are removed, the stories spread through the tribe until there is no one left to tell them, or for stories to be heard.

Except for one, ‘Al Al-Ashirah’, the one who placed back his helmet and returned to our planet, bringing with him the stories of his tribe.

In our species’ not so distant future, we have lost control of our stories.

Our world is now governed by tribal stories in their political, extremist, nationalistic, and sectarian genres. In this future, stories are diagnosed as a disease of the mind. An infection we must be quarantined away from.

In a bid to save itself from its own stories, our species sends forth its seeds into the stars in a mission to populate a new planet far away from the narratives of our own.

Carried on board a mother ship, whose mission is to sow a distant soil with a new, story-less, human tribe.

Each seed is a material that acts as a new technological skin, encasing the human life that grows within it.

A skin that is the final layer of our technological evolution designed to imprison the human instinct to tell stories.

There is no thirst inside this skin, no hunger, no illness or pain. The individual within is rendered self-sufficient, self-reliant and in no need of the collective tribe. The skin, through its obscuring helmet, prevents all human emotions and forms of expression from being transmitted out.

Any attempt to tell a story is caught by algorithms that censor, filter out, and mute through this wearable firewall.

But within this new tribe, the need to share the stories they each carried in isolation only grows stronger.

Until the first helmet is removed and a story is told.

Then the second helmet is removed and a story is first heard.

And when all the helmets are removed, the stories spread through the tribe until there is no one left to tell them, or for stories to be heard.

Except for one, ‘Al Al-Ashirah’, the one who placed back his helmet and returned to our planet, bringing with him the stories of his tribe.

In our species’ not so distant future, we have lost control of our stories.

Our world is now governed by tribal stories in their political, extremist, nationalistic, and sectarian genres. In this future, stories are diagnosed as a disease of the mind. An infection we must be quarantined away from.

In a bid to save itself from its own stories, our species sends forth its seeds into the stars in a mission to populate a new planet far away from the narratives of our own.

Carried on board a mother ship, whose mission is to sow a distant soil with a new, story-less, human tribe.

Each seed is a material that acts as a new technological skin, encasing the human life that grows within it.

A skin that is the final layer of our technological evolution designed to imprison the human instinct to tell stories.

There is no thirst inside this skin, no hunger, no illness or pain. The individual within is rendered self-sufficient, self-reliant and in no need of the collective tribe. The skin, through its obscuring helmet, prevents all human emotions and forms of expression from being transmitted out.

Any attempt to tell a story is caught by algorithms that censor, filter out, and mute through this wearable firewall.

But within this new tribe, the need to share the stories they each carried in isolation only grows stronger.

Until the first helmet is removed and a story is told.

Then the second helmet is removed and a story is first heard.

And when all the helmets are removed, the stories spread through the tribe until there is no one left to tell them, or for stories to be heard.

Except for one, ‘Al Al-Ashirah’, the one who placed back his helmet and returned to our planet, bringing with him the stories of his tribe.

In our species’ not so distant future, we have lost control of our stories.

Our world is now governed by tribal stories in their political, extremist, nationalistic, and sectarian genres. In this future, stories are diagnosed as a disease of the mind. An infection we must be quarantined away from.

In a bid to save itself from its own stories, our species sends forth its seeds into the stars in a mission to populate a new planet far away from the narratives of our own.

Carried on board a mother ship, whose mission is to sow a distant soil with a new, story-less, human tribe.

Each seed is a material that acts as a new technological skin, encasing the human life that grows within it.

A skin that is the final layer of our technological evolution designed to imprison the human instinct to tell stories.

There is no thirst inside this skin, no hunger, no illness or pain. The individual within is rendered self-sufficient, self-reliant and in no need of the collective tribe. The skin, through its obscuring helmet, prevents all human emotions and forms of expression from being transmitted out.

Any attempt to tell a story is caught by algorithms that censor, filter out, and mute through this wearable firewall.

But within this new tribe, the need to share the stories they each carried in isolation only grows stronger.

Until the first helmet is removed and a story is told.

Then the second helmet is removed and a story is first heard.

And when all the helmets are removed, the stories spread through the tribe until there is no one left to tell them, or for stories to be heard.

Except for one, ‘Al Al-Ashirah’, the one who placed back his helmet and returned to our planet, bringing with him the stories of his tribe.

THE CLOCKS ARE STRIKING THIRTEEN

In a global, connected world, truth is mediated and nuanced by a large variety of lenses, contexts and individual perspectives. The idea that global information systems are built on a power structure that prevents us from balanced consideration and informed discussion seems to resonate more than ever today.

For this exhibition, artists were invited to respond to a specific condition of our time: The incessant hunger for truth and the role of storytelling. Encouraged to question the idea of absolute truth, each responded with different and prevalent narratives, from the domestic, to the geo-political, from the spiritual to the trans-historical.

Despite their individuality, the works in this exhibition provoke familiar and overlapping themes - artists express commonalities in their approaches to the subject, and the idea that so often truth really does seem stranger than fiction

Since the earliest times, it has been apparent that we need stories not because they provide valid epistemological descriptions, but because they have a cognitive function: the very act of creating, telling and hearing stories, whether true or not, allows us to make sense of things.

The irony is not lost that in enabling this exhibition at Athr, we have by the very definition of our roles, constructed a certain narrative, or at least selectively presented one. With this in mind we would urge you to construct your own and find the reasons to tell it.

“The truth was a mirror in the hands of God. It fell, and broke into pieces. Everybody took a piece of it, and they looked at it and thought they had the truth.” Rumi