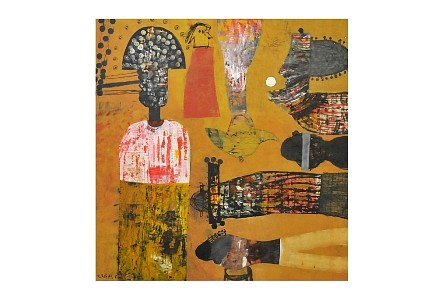

Nasser Al Salem

Kul, 2012

Hand painted on archival paper

100 x 100 cm (39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in.)

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

NAS0039

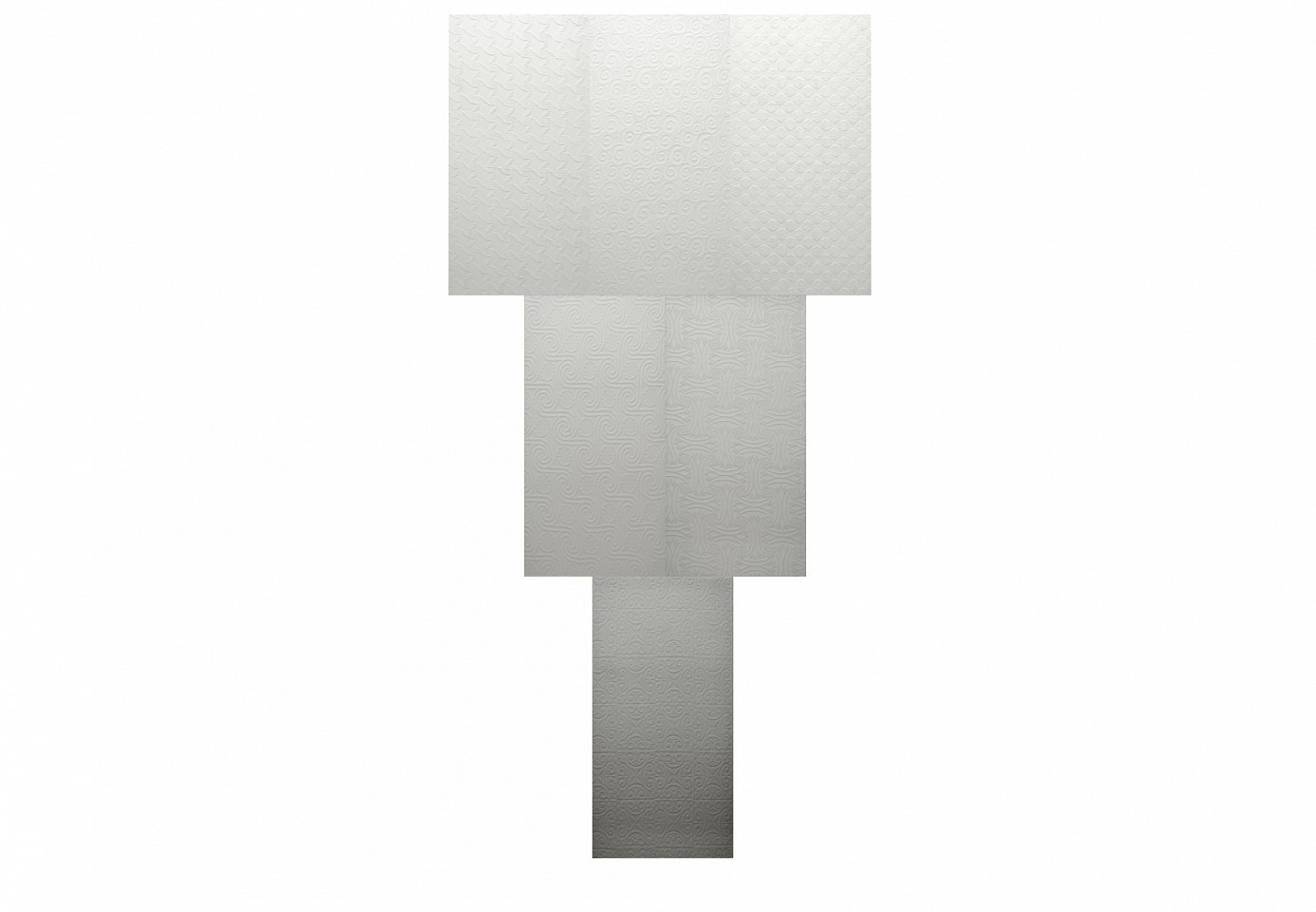

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Ra'i from Ihramat, 2012

Stretched Ihram Fabric over Wooden Frame

240 x 480 cm (94 1/2 x 189 in.)

AYD0396

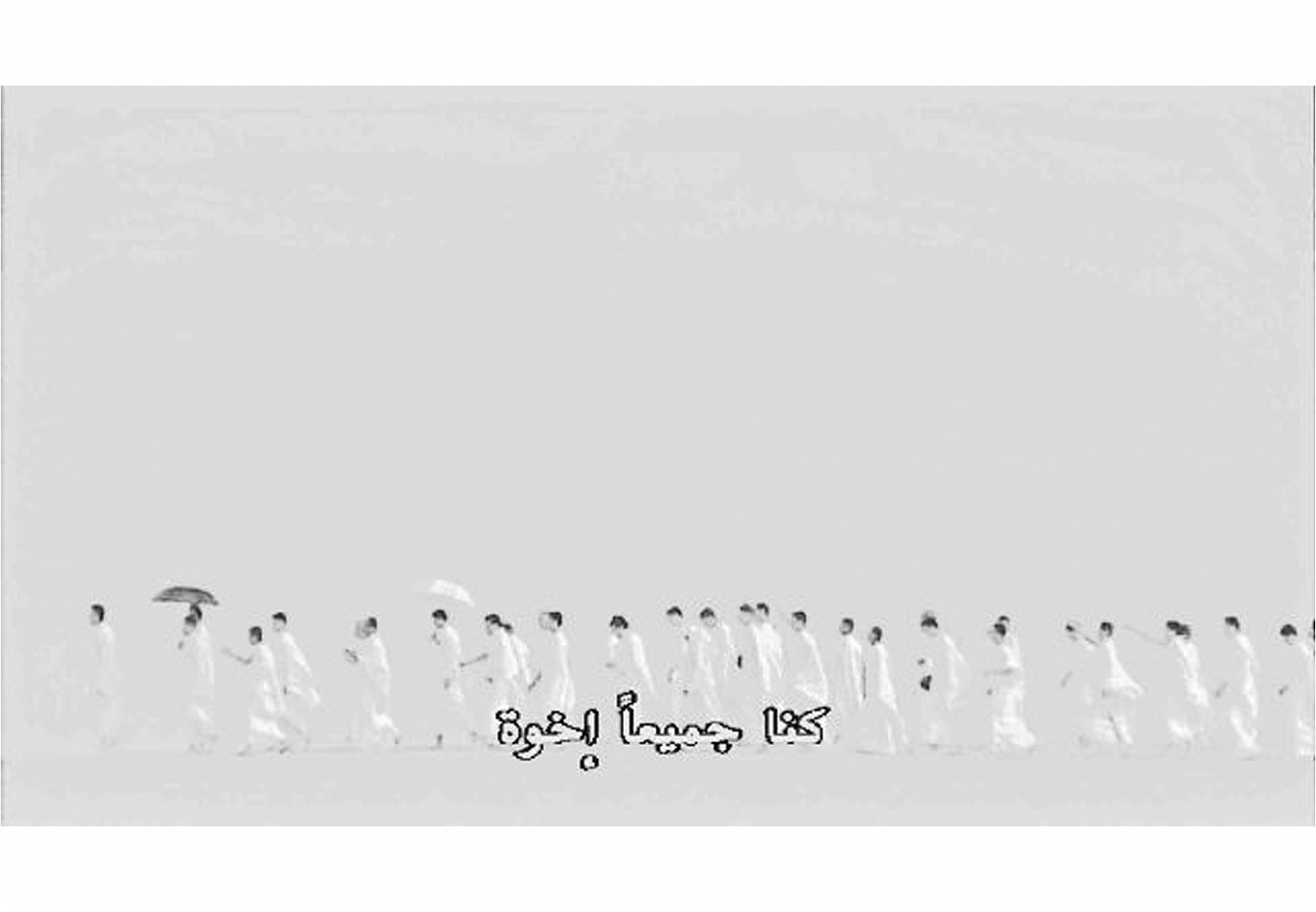

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Kunna Jameean Ekhwa, 2010

Lightbox

87 x 155 cm (34 1/4 x 61 in.)

From Subtitles series, Edition of 3+1 AP, Acquired by The British Museum, London

AYD0298

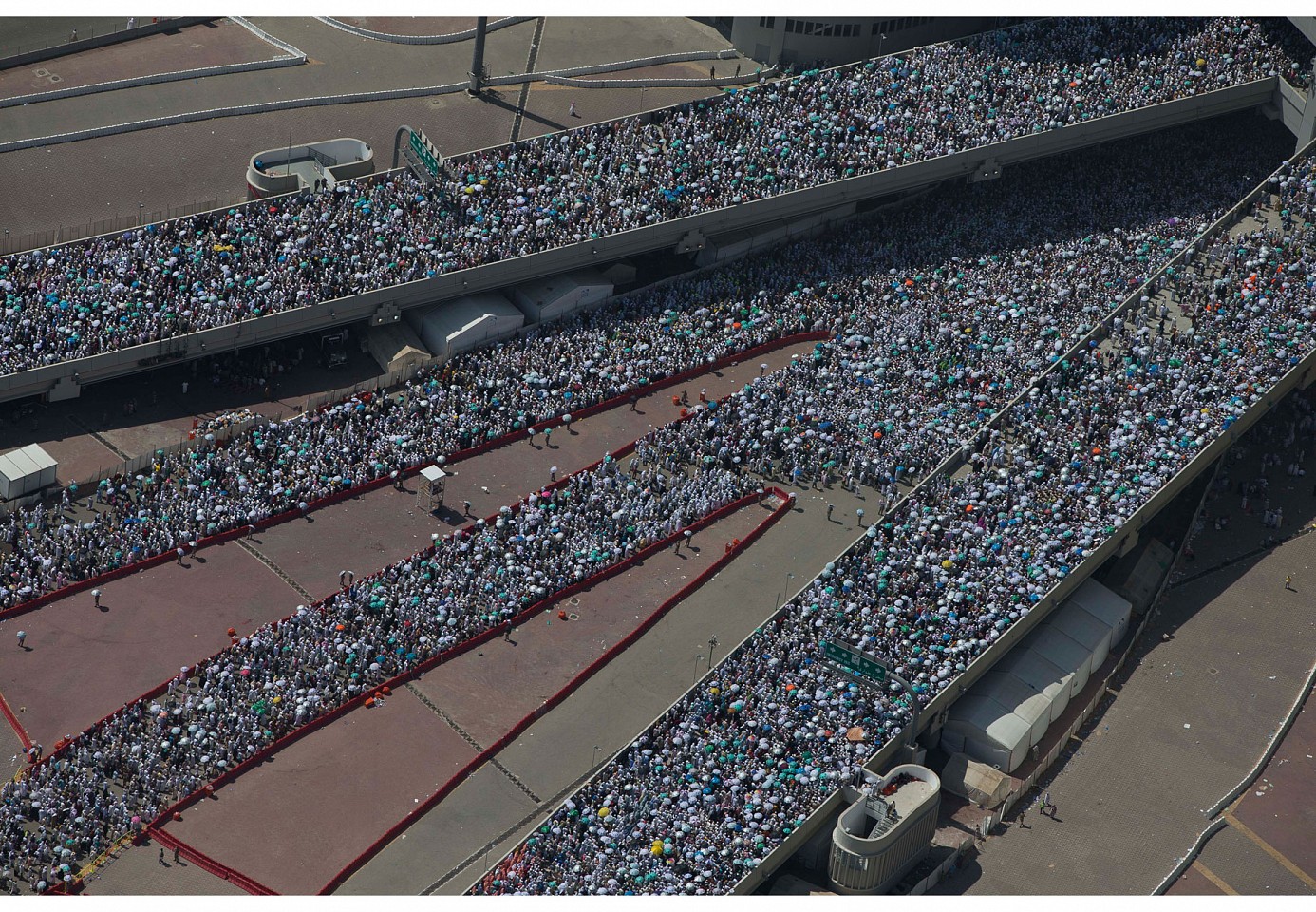

Ahmed Mater

Human Highway, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0043

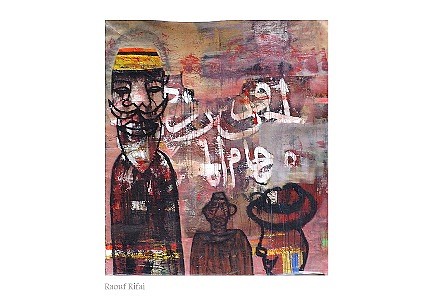

Raouf Rifai

Darawichs, 2011

Acrylic on canvas

140 x 180 cm (55 1/8 x 70 7/8 in.)

RAR0018

Raouf Rifai

Darwich Grafity, 2011

Acrylic on canvas

175 x 150 cm (68 7/8 x 59 in.)

RAR0030

Raouf Rifai

Florescent Clowns, 2011

Acrylic on canvas

150 x 185 cm (59 x 72 7/8 in.)

RAR0034

Raouf Rifai

The Circus, 2011

Acrylic on canvas

189 x 180 cm (74 3/8 x 70 7/8 in.)

RAR0033

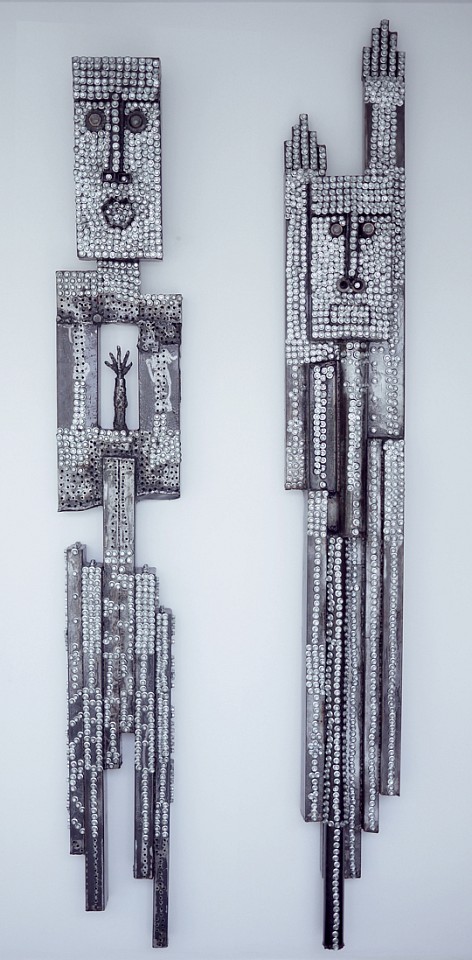

Saddek Wasil

Romeo and Juliet, 2012

Metallic Sculpture

221 x 30 cm

SAW0018

The direct translation of Kul is ‘all’ or ‘everything’. However, the connotation of the word kulin the Arabic language is so much more complex in its all-encompassing meaning and implication of infinity. This meaning is compounded by the artist’s technique of calligraphically depicting the word kul repeatedly, so that it resembles an endless ripple effect.

The impression of never-ending repetition is not merely a reflection of God’s abundance on Earth, but an indication to look both further, and deeper, to penetrate the mere appearance and surface of things, to discover the hidden messages that all aesthetic creation hold.

Once, we thought the atom was the smallest particle, before we discovered that it was made of numerous smaller ones, as we once thought that the extent of our universe was the Milky Way Galaxy, before we discovered that there were hundreds of billions more galaxies out there. As God’s creation is infinite, and while we can say or write the word ‘infinite’ easily, it is impossible to imagine as it extends far beyond the human brain’s capacity for comprehension. Therefore, if one thinks of kul too deeply or for too long, they might realize that it doesn’t exist; there is no ‘all’ or ‘everything’.

Ihramaat is a concept born out of a defining tradition and custom adopted during the holy Hajj pilgrimage. In this series, Daydban uses authentic Ihramat, the customary white cloth worn by pilgrims to Makkah, stretched onto wooden frames and presents them in multiple variations. Traditionally, every man performing his pilgrimage is required to wear white cloth. It erases any distinguishing features between himself and his neighbor and presents them as one, stripped down to their purest form, all equal and united under the same faithful brotherhood.

At a distance, the ihram seems identical as they are of the same scale and essentially plain white cloth, but as you approach, distinct patterns begin to appear. Parallels can be drawn between the piece and social ideals, whereby each panel represents a building block in society. Various groups share differences and similarities in their patterning, yet work together under a grater umbrella to flow in peace and harmony.

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

- Naima Rashid

ART DUBAI LAUNCHES 2012 EDITION WITH ITS MOST INNOVATIVE programme to date

Held under the patronage of H.H. Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai

Art Dubai goes into its sixth year with a dynamic, curated programme, consolidating its position as the key point at which the international art world meets the art scenes of the Middle East and South Asia. After welcoming over 20,000 visitors in 2011, the region’s leading fair features its biggest programme to date, expanding the Global Art Forum, launching artists’ and curators’ residencies, and establishing a year-round education programme.

Art Dubai (March 21-24, 2012), held in partnership with Abraaj Capital and sponsored by Cartier, takes place at its home Madinat Jumeirah.

The fair will welcome a carefully selected roster of 74 galleries from 32 countries, showing work by over 500 artists. The 2012 gallery selection features major new names joining a strong existing base of galleries that have become synonymous with Art Dubai. Key galleries joining in 2012 include Arndt (Berlin), Rodolphe Janssen (Brussels), Lombard Freid Projects (New York), Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke (Mumbai), The Pace Gallery (New York, London, Beijing), Galerie Perrotin (Paris), and Platform China (Beijing).

Galleries returning from 2011 also exemplify the unparalleled regional and international reputation of the fair; they include Athr Gallery (Jeddah), Chantal Crousel (Paris), Experimenter (Kolkata), Goodman (Johannesburg, Capetown), Grey Noise (Lahore), Marianne Boesky Gallery (New York), Sfeir-Semler (Hamburg, Beirut) and The Third Line (Dubai).

“Over the past decade, Dubai has become known as an international art hub,” says Antonia Carver, Art Dubai Fair Director. “This growth has been organic, with a scene characterized by enthusiastic, enquiring audiences and dedicated local patrons. Art Dubai is both a catalyst in this development and illustrative of it.”

“This year’s fair promises to deliver an unrivalled collection of varied yet tailored programmes for everyone, from the world’s leading collectors and art professionals to students and families,” says Antonia Carver. “We’ve been proud to see such enthusiasm and support for Art Dubai from gallerists new and old over the past five years, throughout the Middle East and globally; our partners – galleries, institutions, artists, curators, collectors, sponsors and the media – have been the driving force behind making Art Dubai the distinct cultural platform that it has become.”