Musaed Al Hulis

The Sleep of the Wicked, 2013

Foam upholstered in fabric

120 x 90 x 28 cm (47 1/4 x 35 3/8 x 11 in.)

Edition of 5

MAH0006

Musaed Al Hulis

Grand Design, 2013

Canvas belts on mechanical gears

120 x 12095 x 9570 cm

MAH0005

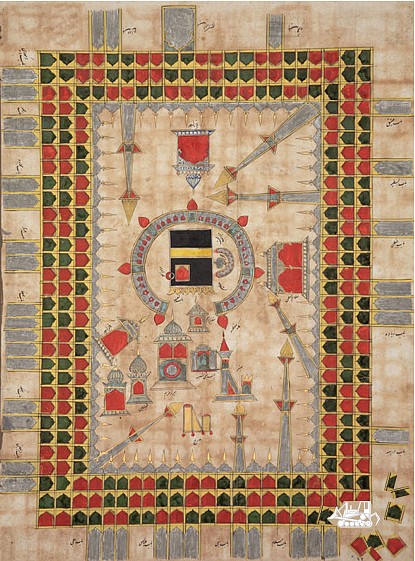

Ahmad Angawi

21st Century Manuscript, 2013

Ink, gold, silver guache on paper

64.7 x 47.5 cm (25 1/2 x 18 3/4 in.)

AHA0000

Rashed Al Shashai

Stopper, 2013

Foam, rubber and steel installation

70 x 120 x 120 cm (27 1/2 x 47 1/4 x 47 1/4 in.)

RAS0003

Rashed Al Shashai

The View, 2013

Television screen and wooden shutters

80 x 120 x 13 cm (31 1/2 x 47 1/4 x 5 1/8 in.)

Edition of 3

RAS0005

Basmah Felemban

Jeem, 2012

Acrylic on plywood

115 x 115 cm (45 1/4 x 45 1/4 in.)

Edition of 3

BAF0002

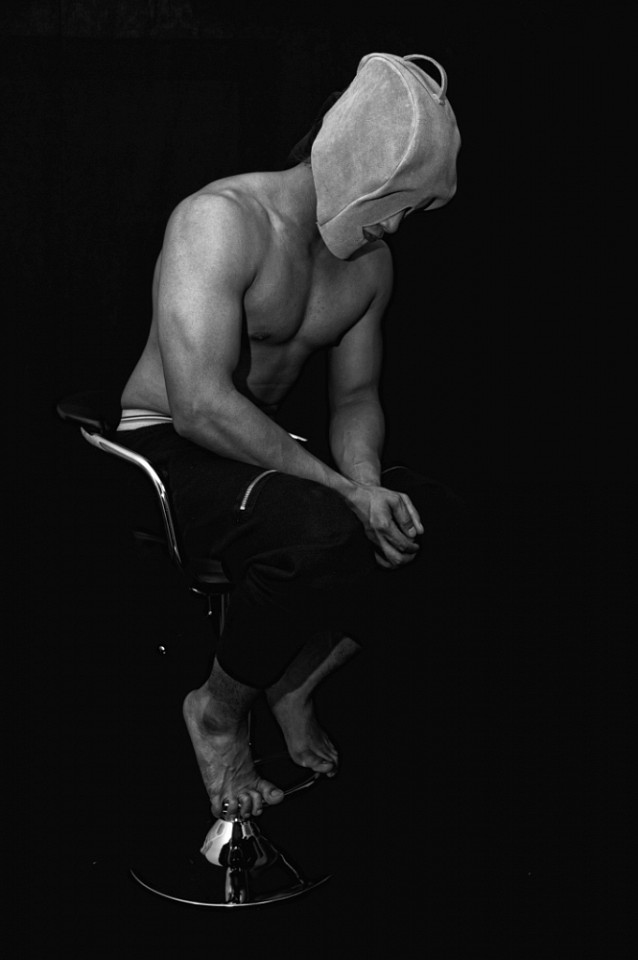

Sara Khoja

The Hood, 2013

Digital Print

90 x 60 cm (35 3/8 x 23 5/8 in.)

Edition of 5

SAK0000

Musaed Al-Hulis’s The Sleep of the Wicked is a dark caution against corruption and immorality, prompting the viewer to always heed the consequences of their actions, and reminding one that life is ephemeral and that our deeds define our future in the unknown hereafter.

Rituals are typically defined by a set of actions that have symbolic value. Islam is a religion of rituals; of daily prayers, of umra and the hajj to name but a few. Whilst the majority of the masses might perform these rituals diligently, I sometimes feel that they have become a mechanical process.

Yet, the universe is built upon mechanical processes; night follows day as the Earth rotates on its axis, the moon rotates around the Earth, the Earth rotates around the sun, and all works together in perfect harmony as part of God’s grand design. I often wonder, where do we fit in?

Is it a coincidence that one of the most important rituals that we perform, the circumambulation of the Ka’ba, mimics the movements of the heavens? Perhaps through these rituals, we are playing our own part in the mechanism of the universe, in God’s grand design, for even in the most complicated machine, the smallest gear has a role to play.

This work is an attempt to replicate a 17th century Hajj certificate manuscript, known in Arabic as a shahadah, a term which refers to the certificate as a witness, proof of having performed the Hajj.

The certificate depicts the holy Ka’ba in a two-dimensional manner that became the standard way to represent the sanctuary on manuscripts, tile-work and Hajj certificates throughout this period. The 17th century version clearly depicts the riwaq (arcades), the architectural feature of the Haram Al-Sharif that is said to date back to the Abbasid Empire. Much of the riwaq have been destroyed as part of the expansion plans of the Haram Al-Sharif, and preparations are being made for further demolishing and expansion.

I have decided to embark upon an adaptation of the portrait, one that reflects our times. I have decided to replicate the certificate as accurately as possible, except for one slight modification. This is my shahada, the proof of what I am witness to. (Ahmed Angawi)

Following in the steps of Mona Hatoum, Al-Shashai has transformed a familiar everyday object into a large-scale installation. By transforming the size of the object, the artist has stripped it of all its function, and therefore its identity. In its grandiose proportions, it has become a surreal caricature of its former self. The audience, faced with this familiar yet awkward, and out of place object, will succumb to the natural human tendency to categorize, and will try to place it. The artist seeks to encourage this activity in the hope that in attempting to discover the true nature of the object, light can be shed on our own human condition.

Rashed Al-Shashai’s The View is a commentary on the systematic filtering of information by the media. The work first appears as window shutters with lights flickering from behind them, drawing the viewer’s curiosity. However, even as one approaches, the scene beyond the shutters remains unclear, fulfilling the shutters’ function and purpose, and the only indication of what is beyond is the faint sound of an anchorman presenting a news story, but will we ever experience the news without the screen, and know the real story?

Jeem is inspired by a poem written by the Sufi scholar Mohammed Abdul Jabbar Al-Nafari on the science of letters:

الØر٠يسري Øيث القصد

جيم جنة جيم جØيم

وقال لي من أهل النار، قلت أهل الØر٠الظاهر،

قال من أهل الجنة، قلت أهل الØر٠الباطن،

قال ما الØر٠الظاهر، قلت علم لا يهدي إلى عمل

قال ما الØر٠الباطن، قلت علم يهدي إلى Øقيقة

A letter leads the way to intention, H, heaven, H, Hell.

He said to me ‘who are the people of Hell?’, I said ‘the people of the outer letters’

He said to me ‘who are the people of Heaven? I said ‘the people of the inner letters’

He said what is the outer letter? I said ‘wisdom that does not lead to work’

He said what is the inner letter? I said ‘wisdom that leads to truth’.

The poem sheds light on a fascinating and mysterious aspect of the Arabic language. Many Islamic scholars believe that there are two facets to every letter, al-zaher - an outer facet and al-baten - an inner facet. The outer relates to the function of the letter in everyday use. The inner relates to the hidden character of the letter; Ibn Arabi said “letters are like a nation of individuals, each with his own duty and obligation”, implying that each letter has its own existence and personality, that is longing to be acknowledge and admired.

The Hood explores a neo-type of slavery. The hood represents the tools that are used in this day and age to keep human beings in control, and at the mercy of others.

I’d like to tell the story of when I began the process of this artwork which I believe illustrates the message better than any statement that I could write:

When I was attempting to find a manufacturer for the hood used in the image (based on the hoods used in falcon training), I thought I found a man who understood exactly what it was that I wanted and commissioned him to make it. When I went to collect it, I was surprised to find that he had perforated holes for the eyes and the ears. When I sternly asked him why he had done so, when I thought that I had made myself perfectly clear, he replied ‘But how is the person wearing it supposed to see and to hear?’, to which I responded ‘That my friend, is precisely the point. He’s not supposed to see and to hear’. Needless to say he thought I was insane. (Sara Khoja)

To draw a line in the sand is a symbolic gesture that denotes a point beyond which one cannot go any further. It is a gesture of daring, a challenge, to test a person’s courage and resolve to take the next step. However, at the end of the day, it is but a line in sand, a transitory mark that will fade as it is dissolved by the very sand it is drawn on. It is but a harmless illusion of danger, a line whose substance is more in mind than in matter.

Each of the participating artists is pushing the boundaries, and braving the limitations set by their environment, limitations that are both real; in the form of the everyday obstacles an artist faces, and perceived; in the form of the restrictions imposed upon themselves in their imagination. The latter are the most difficult to overcome.

These young artists are conquering these mental obstacles, and stepping over the line in the sand. Their works are a confrontation of themselves in their attempts to conceptualize ideas and notions that are dearest to their hearts and at the forefronts of their minds, be they personal, spiritual, social or political, with the sole purpose of dissolving the barriers that separate us via a universal form of communication.

A Line in the Sand does not just reveal artists overcoming barriers. There are two sides to every barrier, as there are two faces to every coin. The exhibition seeks to flip the coin, as the artists themselves not only step over the line, but draw it; the artists aim to challenge and engage the visitors in turn, not merely to view the works, but in fact to interpret them, for only with this two-way exchange can communication and dialogue succeed, and barriers truly dissolve.