Musaed Al Hulis

The Sleep of the Wicked 2, 2013

Foam upholstered in fabric

120 x 98 x 28 cm (45 1/4 x 35 3/8 x 11 in.)

Unique (Variation of 2/5)

Musaed Al Hulis

Tighten Your Belt, 2013

Canvas belts on mechanical gears

65x65, 45x45, 35x35 cm

Unique (Variation of 2/5)

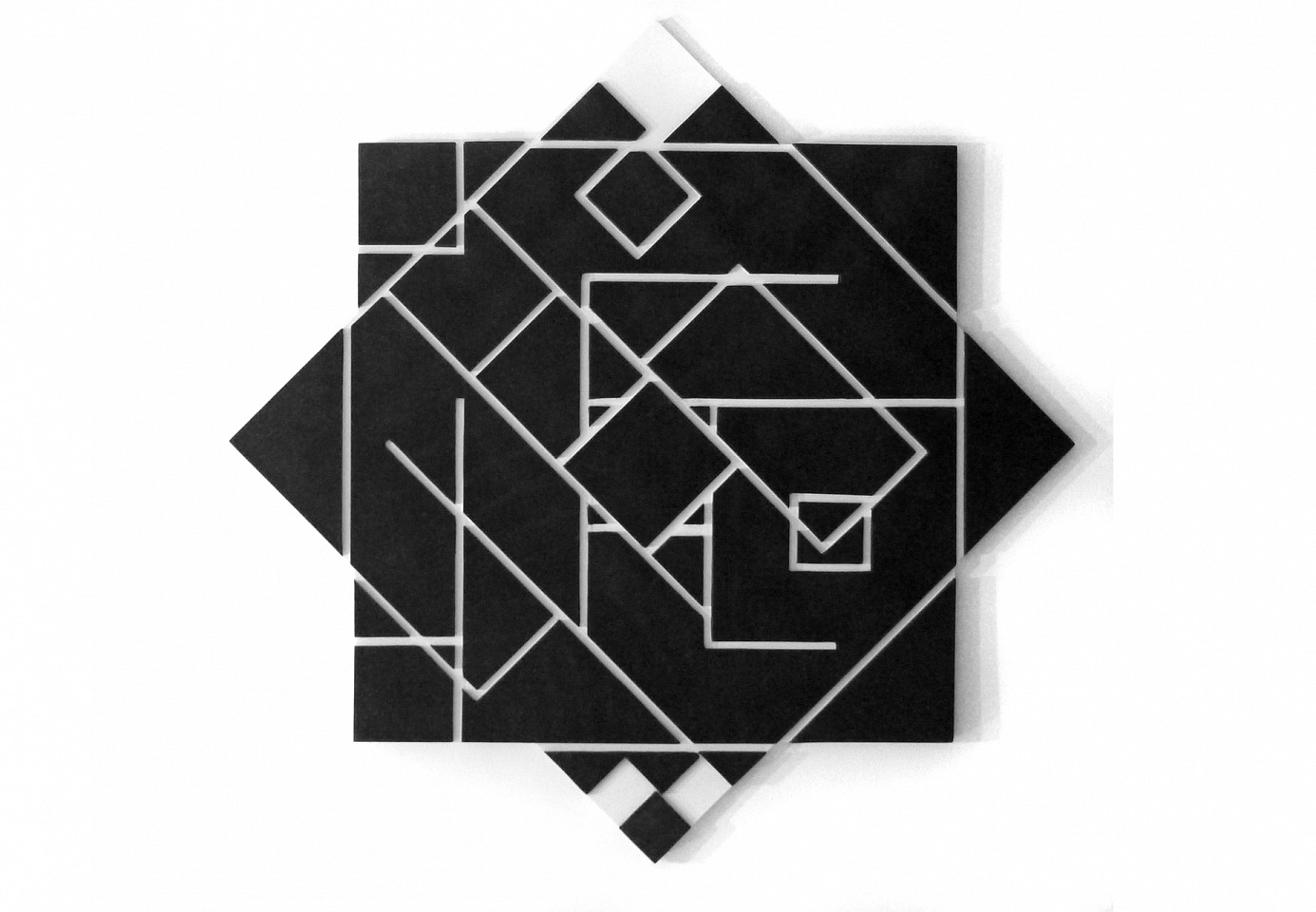

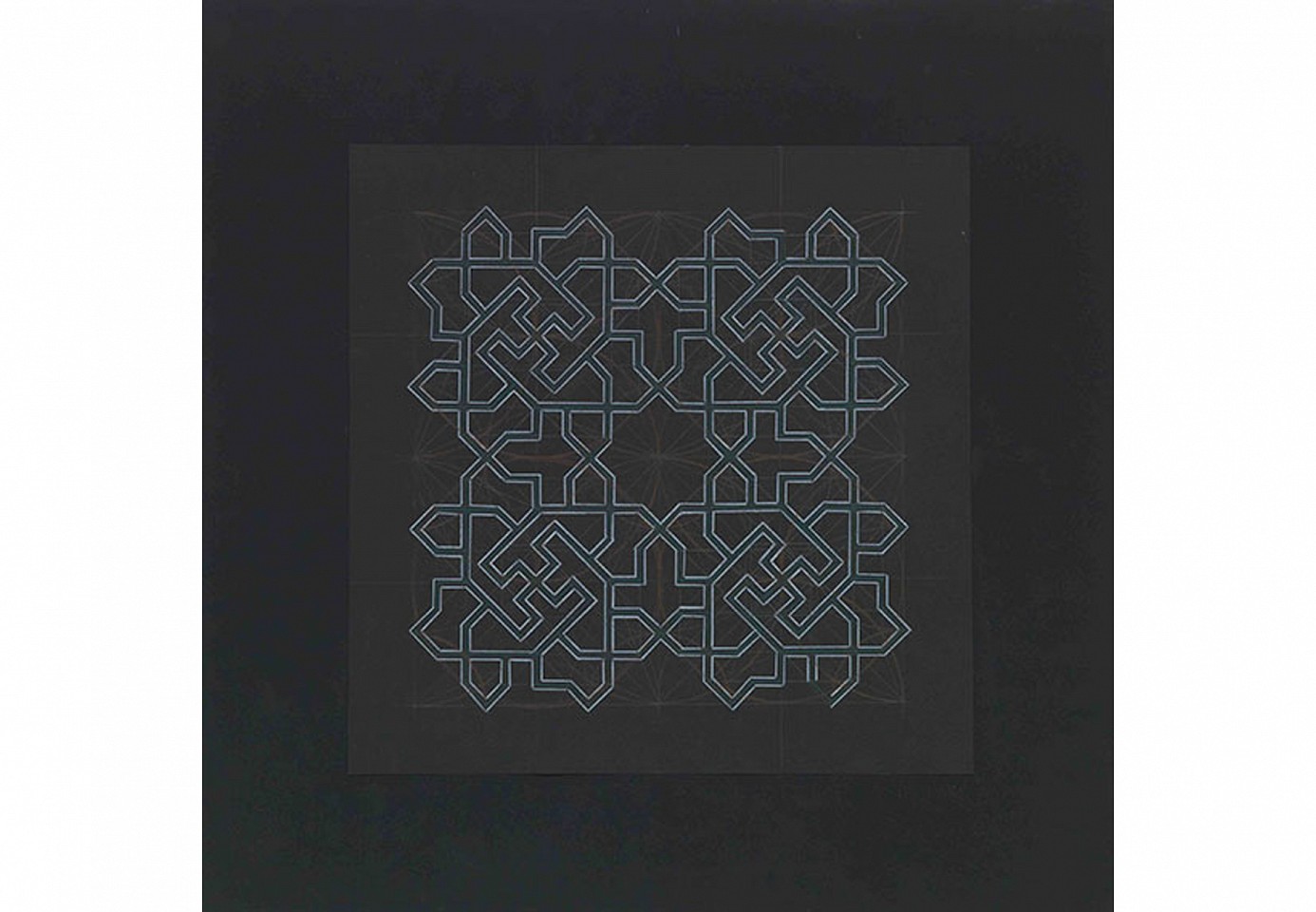

Basmah Felemban

Jeem, 2012

Acrylic on plywood

115 x 115 cm (45 1/4 x 45 1/4 in.)

Edition of 3

BAF0002

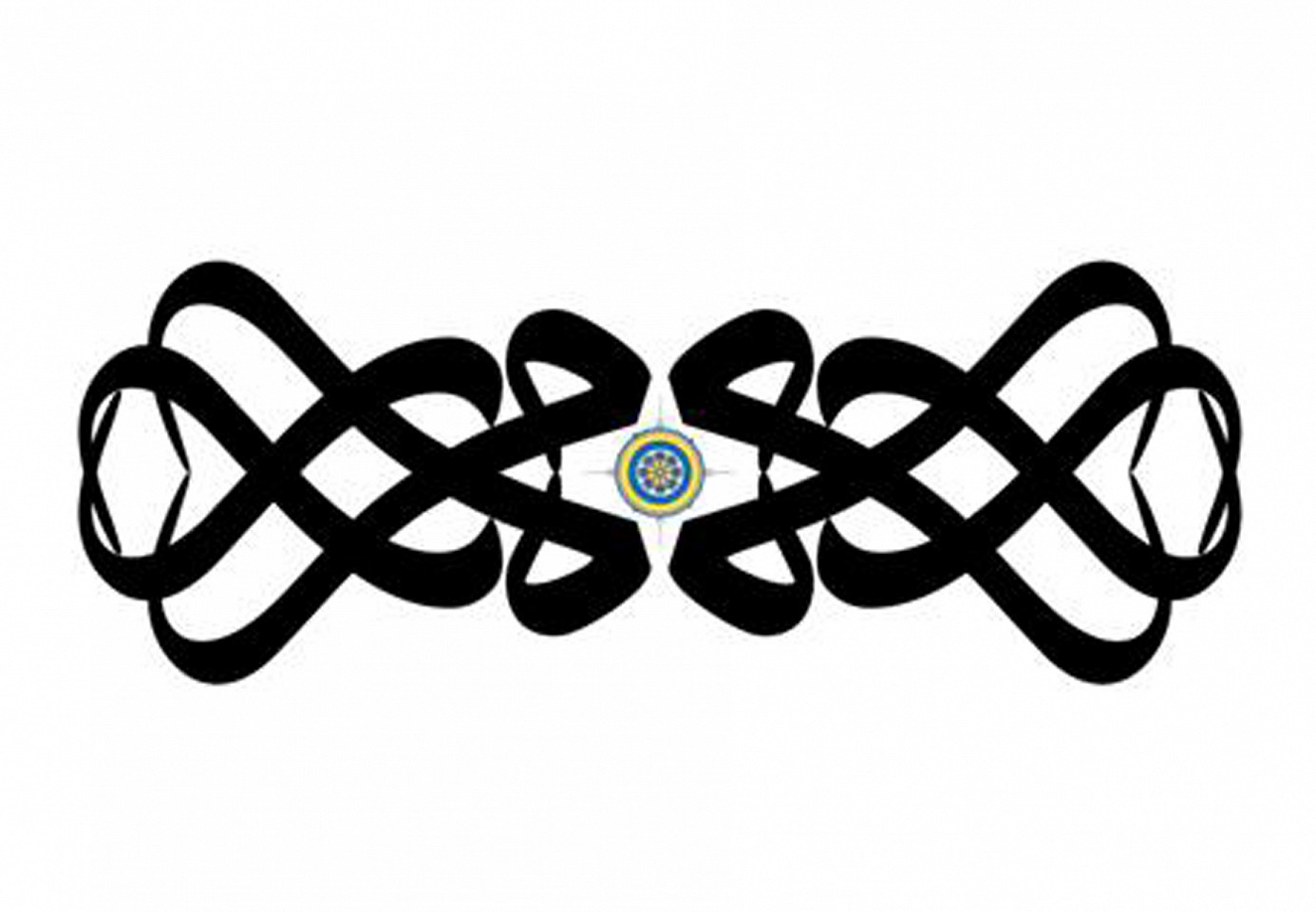

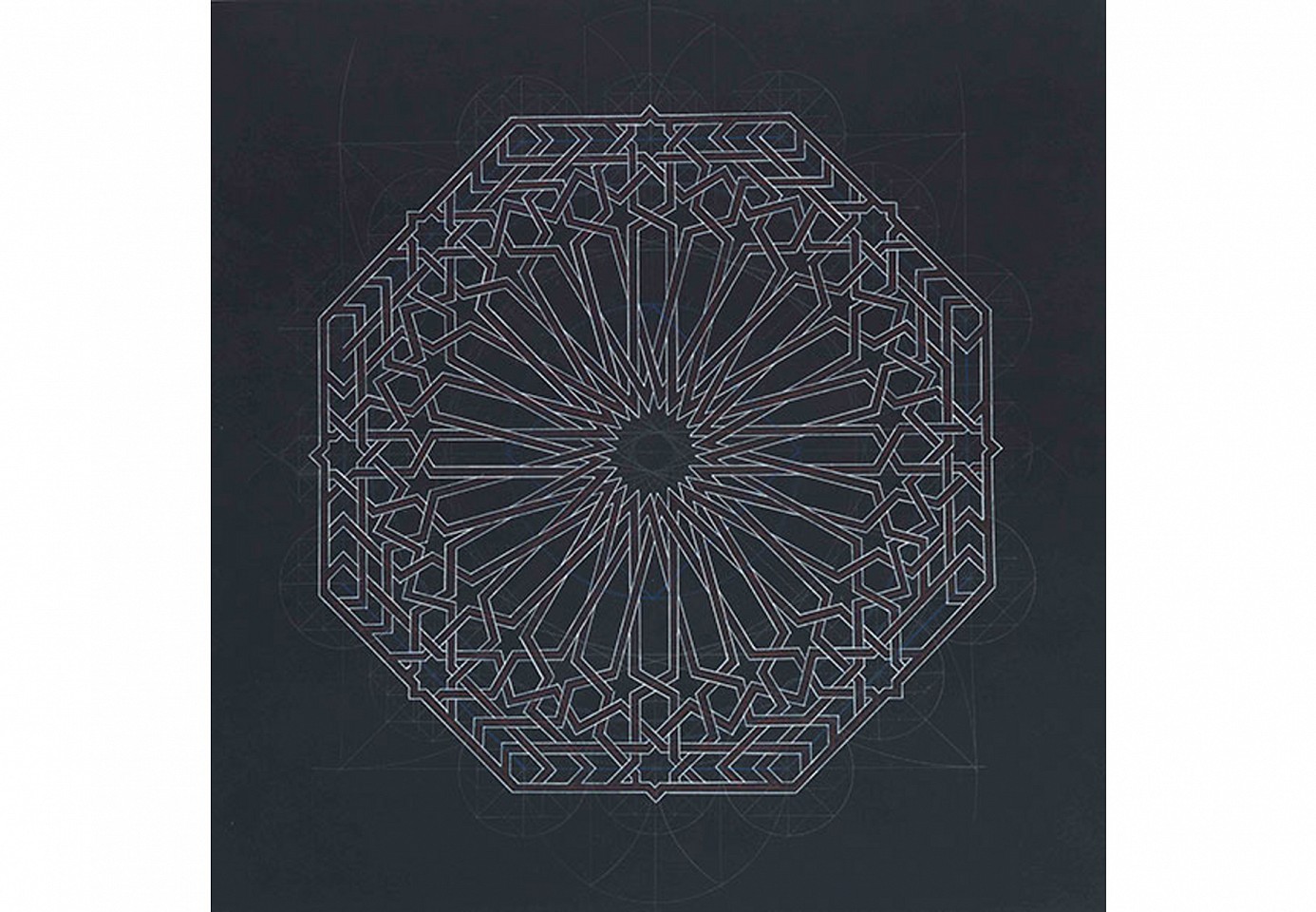

Nasser Al Salem

Zamzam, 2010

Embossed with Silk Screen on paper, hand painted with Gold Leaf

Edition of 3 + 1 AP / Edition of 20 + 2 AP, Acquired by The British Museum, London

NAS0061

Nasser Al Salem

No. 63, 2011

Mixed Media

200 x 103 cm (78 3/4 x 40 1/2 in.)

From City of Nomads series

NAS0077

Ibrahim Abumsmar

The Black Stone, 2012

Corian Sculpture

200 x 183 x 130 cm (78 3/4 x 72 x 51 1/8 in.)

IAM0028

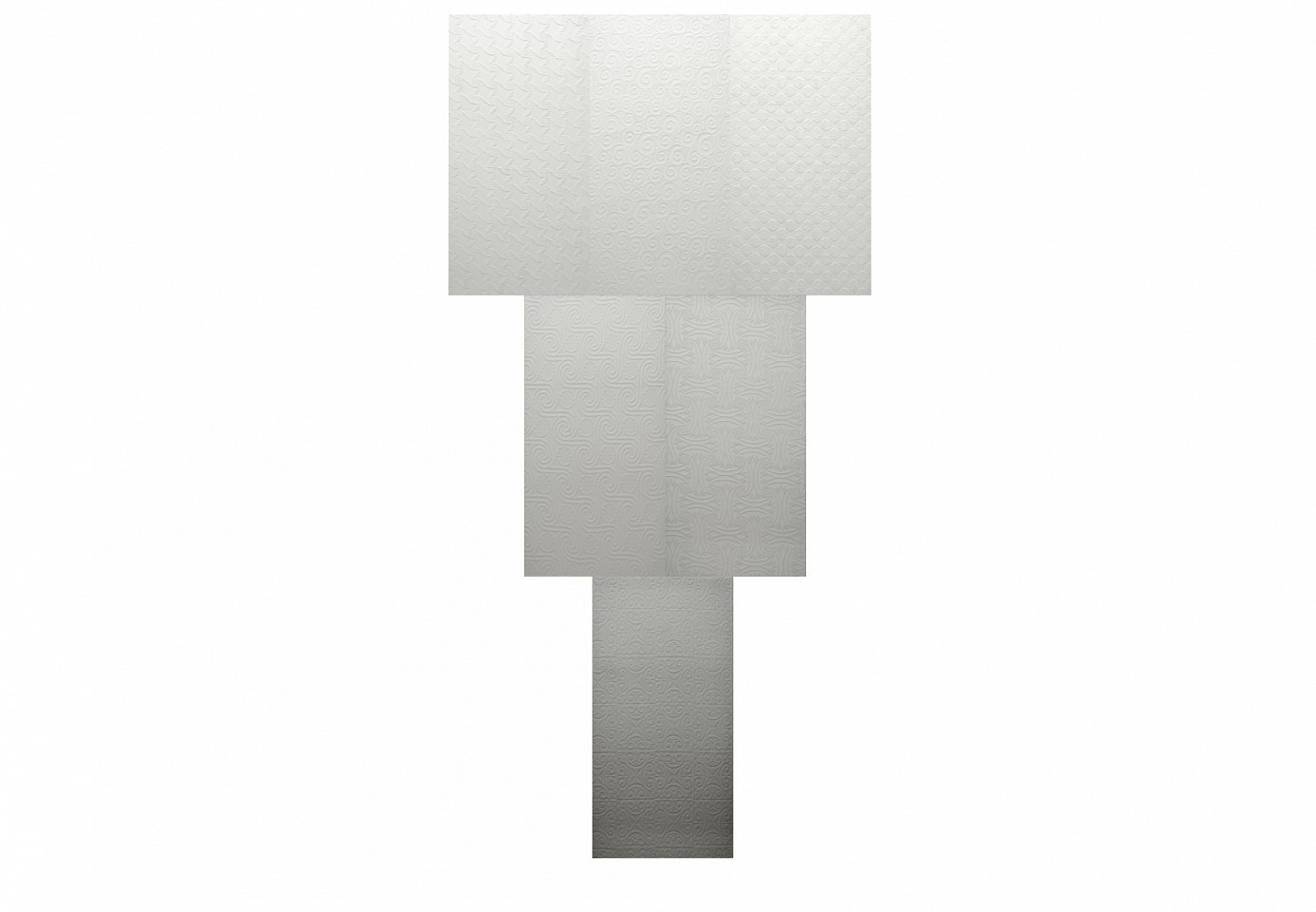

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Ra'i from Ihramat, 2012

Stretched Ihram Fabric over Wooden Frame

240 x 480 cm (94 1/2 x 189 in.)

AYD0396

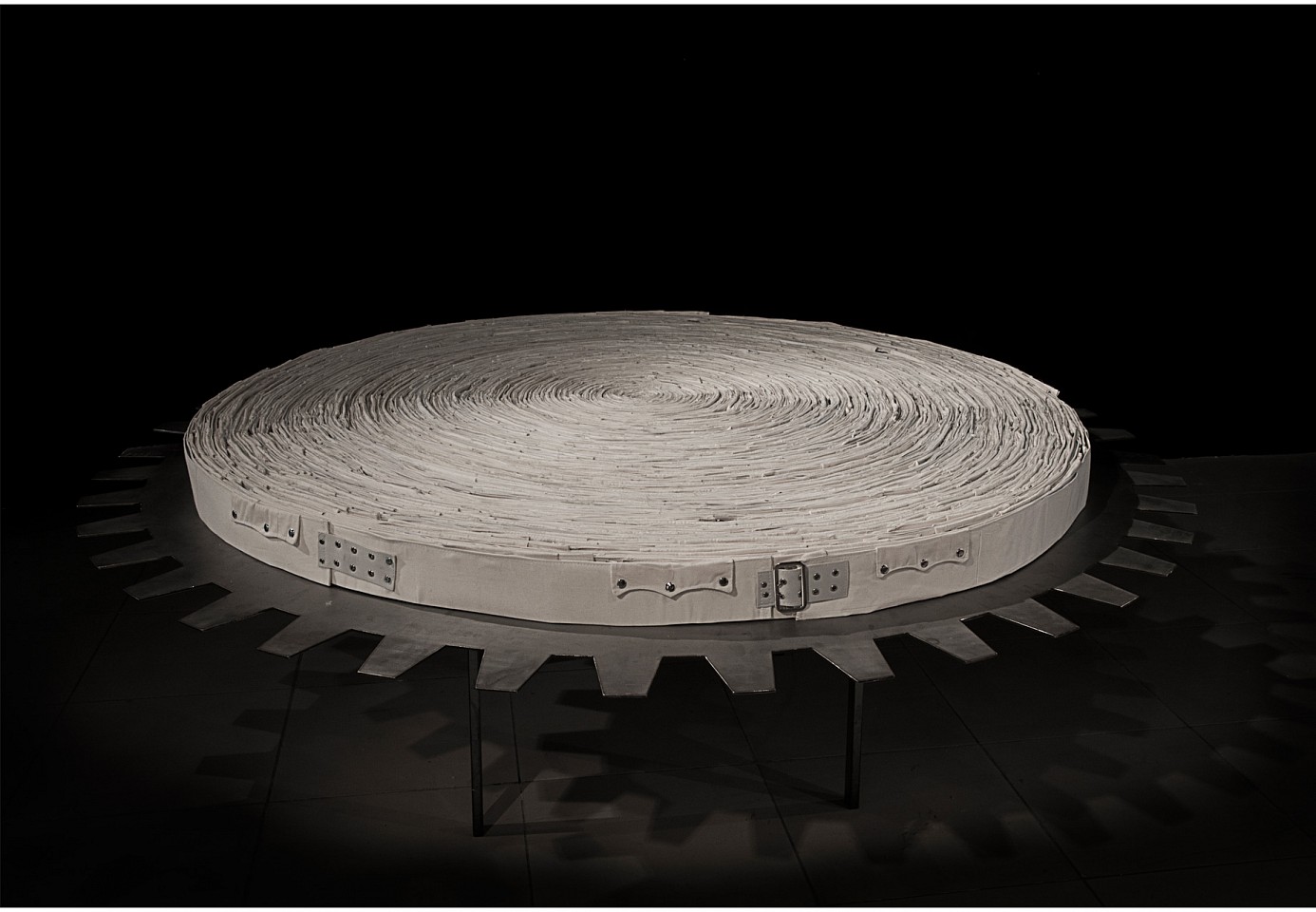

Musaed Al Hulis

Grand Design, 2013

Canvas belts on mechanical gears

120 x 12095 x 9570 cm

MAH0005

Musaed Al Hulis

The Sleep of the Wicked, 2013

Foam upholstered in fabric

120 x 90 x 28 cm (47 1/4 x 35 3/8 x 11 in.)

Edition of 5

MAH0006

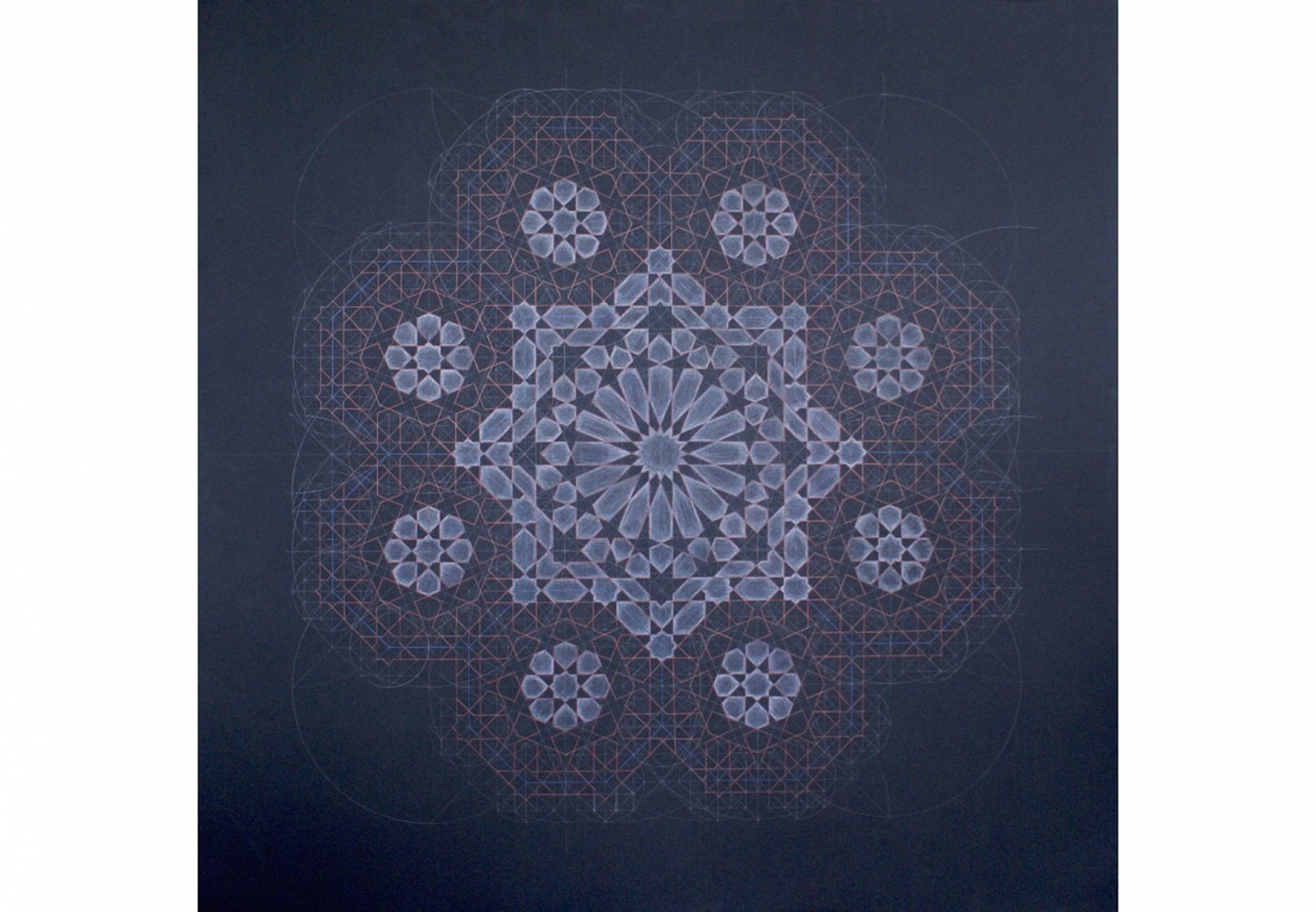

Dana Awartani

Abdulrahman (Slave of The Compassionate), 2012

Pencil on mount board

100 x 100 cm (39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in.)

DAN0000

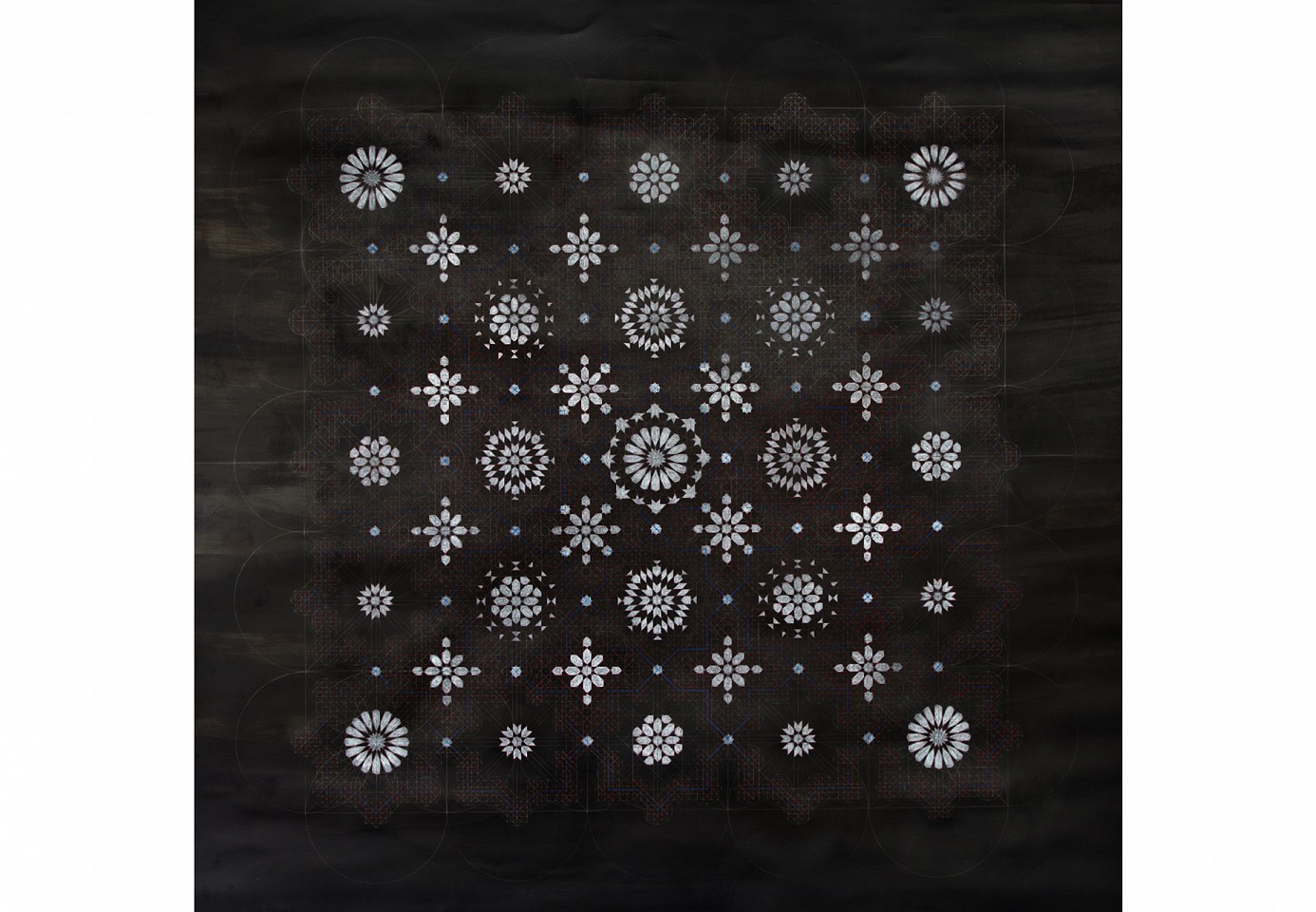

Dana Awartani

Abdulraheem (Slave of The Merciful), 2012

Pencil on mount board

100 x 100 cm (39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in.)

DAN0001

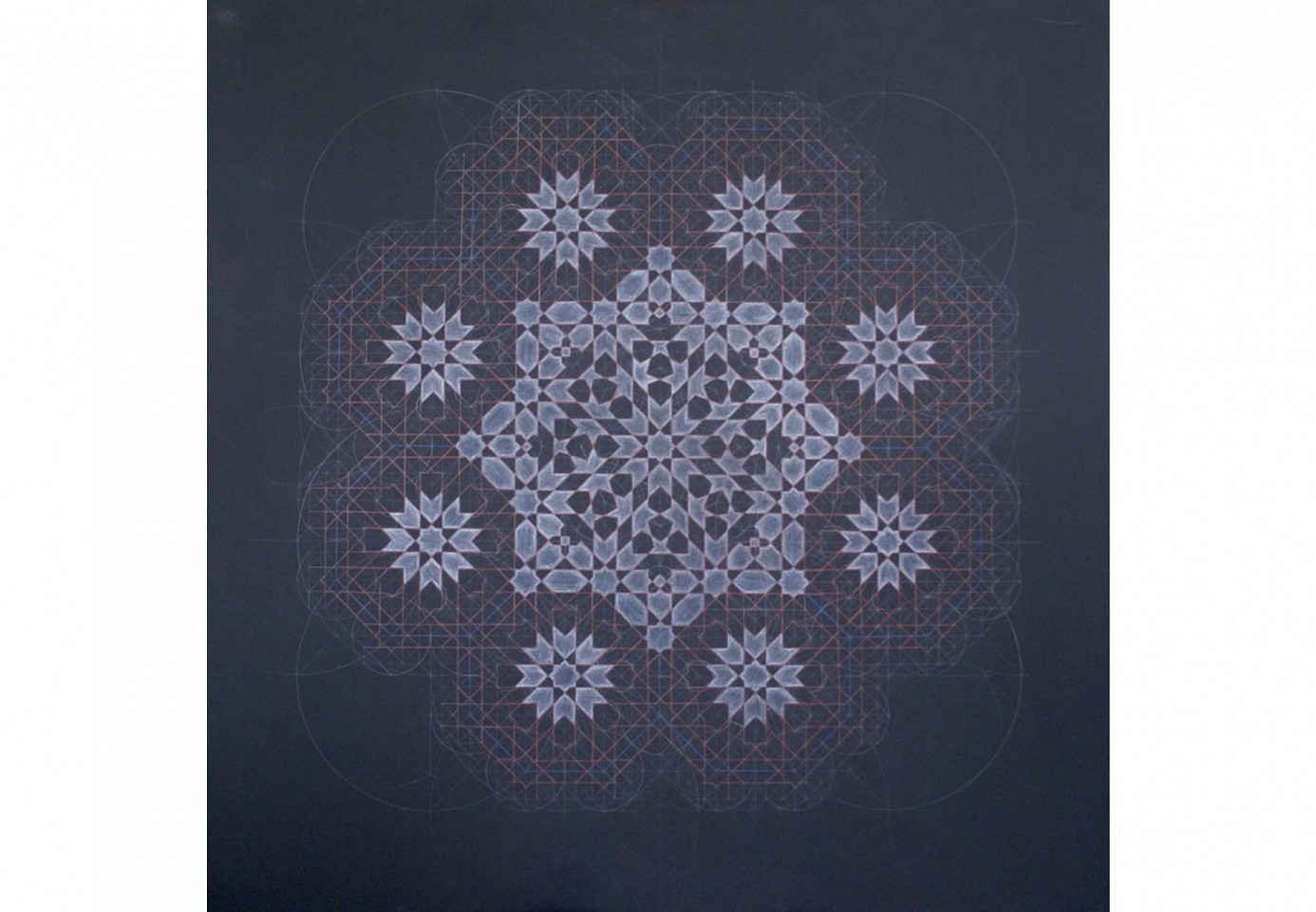

Dana Awartani

Symetry, 2011

Pencil on black paper

27 x 27 cm (10 5/8 x 10 5/8 in.)

DAN0005

Dana Awartani

Gamar (The Moon), 2011

Pencil on black paper

48.5 x 48.5 cm (19 1/8 x 19 1/8 in.)

DAN0006

Dana Awartani

The Breath of the compassionate, 2013

Pencil on black paper

150 x 150 cm (59 x 59 in.)

DAN0004

Jeem is inspired by a poem written by the Sufi scholar Mohammed Abdul Jabbar Al-Nafari on the science of letters:

الØر٠يسري Øيث القصد

جيم جنة جيم جØيم

وقال لي من أهل النار، قلت أهل الØر٠الظاهر،

قال من أهل الجنة، قلت أهل الØر٠الباطن،

قال ما الØر٠الظاهر، قلت علم لا يهدي إلى عمل

قال ما الØر٠الباطن، قلت علم يهدي إلى Øقيقة

A letter leads the way to intention, H, heaven, H, Hell.

He said to me ‘who are the people of Hell?’, I said ‘the people of the outer letters’

He said to me ‘who are the people of Heaven? I said ‘the people of the inner letters’

He said what is the outer letter? I said ‘wisdom that does not lead to work’

He said what is the inner letter? I said ‘wisdom that leads to truth’.

The poem sheds light on a fascinating and mysterious aspect of the Arabic language. Many Islamic scholars believe that there are two facets to every letter, al-zaher - an outer facet and al-baten - an inner facet. The outer relates to the function of the letter in everyday use. The inner relates to the hidden character of the letter; Ibn Arabi said “letters are like a nation of individuals, each with his own duty and obligation”, implying that each letter has its own existence and personality, that is longing to be acknowledge and admired.

Zamzam is a calligraphic representation of the word ‘zamzam’, a miraculously generated source of water from God. The composition is significant to the holistic symbolic meaning of the piece. The word is designed to be read from left to right, right to left, up to down and down to up, echoing universal ways of reading. Such flow in the direction of this also depicts Hajar pacing between Safa and Marwa in order to find the source of the holy zamzam water. It also represents the angel Gabriel’s large wingspan, who was responsible for indicating to Hajar where to stomp her foot in order to reveal the source. At the heart of the print lies an intricately designed and manipulated 8-point star; this is where God is believed to rest upon his throne. According to Islamic tradition, the 8-point star is also a sign for infinity, which coincidentally, is also the general shape this piece has formed, implying Islam’s everlasting and unbreakable cycle.

Zamzam has been acquired by The British Museum in 2011.

Ihramaat is a concept born out of a defining tradition and custom adopted during the holy Hajj pilgrimage. In this series, Daydban uses authentic Ihramat, the customary white cloth worn by pilgrims to Makkah, stretched onto wooden frames and presents them in multiple variations. Traditionally, every man performing his pilgrimage is required to wear white cloth. It erases any distinguishing features between himself and his neighbor and presents them as one, stripped down to their purest form, all equal and united under the same faithful brotherhood.

At a distance, the ihram seems identical as they are of the same scale and essentially plain white cloth, but as you approach, distinct patterns begin to appear. Parallels can be drawn between the piece and social ideals, whereby each panel represents a building block in society. Various groups share differences and similarities in their patterning, yet work together under a grater umbrella to flow in peace and harmony.

Rituals are typically defined by a set of actions that have symbolic value. Islam is a religion of rituals; of daily prayers, of umra and the hajj to name but a few. Whilst the majority of the masses might perform these rituals diligently, I sometimes feel that they have become a mechanical process.

Yet, the universe is built upon mechanical processes; night follows day as the Earth rotates on its axis, the moon rotates around the Earth, the Earth rotates around the sun, and all works together in perfect harmony as part of God’s grand design. I often wonder, where do we fit in?

Is it a coincidence that one of the most important rituals that we perform, the circumambulation of the Ka’ba, mimics the movements of the heavens? Perhaps through these rituals, we are playing our own part in the mechanism of the universe, in God’s grand design, for even in the most complicated machine, the smallest gear has a role to play.

Musaed Al-Hulis’s The Sleep of the Wicked is a dark caution against corruption and immorality, prompting the viewer to always heed the consequences of their actions, and reminding one that life is ephemeral and that our deeds define our future in the unknown hereafter.

Jeddah’s Athr Gallery comes to Doha, Qatar this month to collaborate with the city’s Katara Cultural Village on ‘Show Of Faith’, a major, multi-media group exhibition by Saudi Arabian artists opening on July 11th and running until August 31st.

As part of a groundswell of activity from the Saudi Arabian gallery, that has seen its artists exhibit in London, Berlin, Venice and Basel in the past few months, ‘Show Of Faith’ marks Athr Gallery’s inaugural foray into the burgeoning art scene of Doha.

Taking its cue from the imminent Ramadan season, a time of contemplation and spiritual regeneration for Muslims worldwide, ‘Show Of Faith’ offers perspectives, insights and reflections on the essence of faith, both within the precepts and traditions of Islam, and beyond, as a universal source of sanctuary and solace.

‘Show Of Faith’ questions how the proximity of Mecca has affected the worldview of the artists who have grown up in the area – artists such as Ibrahim Abumsmar, Nora Alissa, Dana Awartani, Ayman Yossri Daydban, Basmah Felemban, Musaed Al Hulis, Nasser Al Salem and Noha Al Sharif.

Discussing themes ranging from ritual, tradition and history to the contemporary manifestations of faith and devotion, ‘Show of Faith’ presents a broad spectrum of artistic styles and forms, that draw heavily on the geometrical abstractions of traditional Islamic art, blending smoothly with the present-day approaches and techniques.

Ibrahim Abumsmar (b.1976) presents ‘The Blackstone’, an interactive sculpture inspired by the black stone in Mecca’s Grand Mosque. Here, Abumsmar has incorporated small shards of broken mirror to reflect and draw the viewer into becoming an intrinsic part of the work and by extension, atomizing the body into the greater whole of the piece. Dana Awartni references traditional geometric forms in ‘Qamar’, ‘Symmetry’, ‘AbdulRaheem’ and ‘AbdulRahman’ in pencil-drawn forms, signifying the omniscient bearing of Allah in a throne, flanked by angels.

Ayman Yossri Daydban (b. 1966), whose ‘Subtitles’ series was critically-acclaimed at Berlin’s ABC fair last September, is featured here in a stylistic about-turn, with ‘Ra’i’ (The Shepherd), a simple, fabric and wooden structure that utilizes the ‘ihramat’ cloth traditionally worn by pilgrims to Mecca. The ‘ihramat’ is intended to equalize all visitors to Mecca, regardless of status, origin or background.

In his series of frame installations, here ‘Ihramat’ are stretched precisely over groups of square grids, denoting building blocks of society and addressing the paradoxical unity and multitudes of identity found within the Hajj pilgrimages.

Musaid Al Hulis (b. 1974) works predominantly in the fields of design and installation. With two pieces in ‘Show of Faith’, he takes a wryly humorous approach to ritual and order, as a central part of the religious faith and the spiritual certainty and solace found within. ‘Tighten Your Belt’ is a formally-inventive sculpture of canvas belts on metallic, mechanical gears. It references the mass movements around the Ka’aba in Mecca as a metaphor for the interlocking harmony and functioning of the universe, and as with Yossri Daydban’s work, manages to elicit a sense of the individual as a small, but essential cog within a spiritual whole. His ‘Sleep Of The Wicked’, meanwhile, sends a cautionary message of moral warning, amidst its deceptively-cheery floral motifs and classical architectural forms, realized in the form of a bed.

Noor Alissa’s ghostly photographs have been exhibited previously in London, last year. Here, two examples from the ongoing ‘Epiphamania’ series invoke the spiritual atmosphere of Mecca, in layered multiple-exposure experimental pieces that deinterlace people, motions and place in simultaneous settings. Meanwhile Basmah Felamban (b.1990) comes from a graphic design background, which lends itself perfectly to the appropriation and utilization of Islamic forms. ‘Jeem’ layers two calligraphic shapes over each other to form an eight-point star. ‘Sidana’ meanwhile references the central tenet of infinity with a marker on acrylic mirror.

Nasser Alsalem (b.1984) presents two very different pieces – ‘City Of Nomads’, a major shift in the artist’s practice from his usual calligraphic-based work, discusses the transient, often threatened way of life of desert nomads, an intrinsic element of Gulf Arab history now in danger of vanishing entirely under successive waves of modernization. In his other piece at ‘Show Of Faith’, we see a more familiar idiom as Alsalem presents ‘Zamzam’, a holy metaphor for Allah within a complex calligraphic representation of ‘Zamzam’, the holy water which springs in Mecca, reputed to have been revealed by the archangel Gabriel. Alsalem has designed the piece to be read in a variety of directions, from left to right and up and down.

Finally, Noha Al-Sharif (b.1980) is featured in ‘Show of Faith’ as one of Saudi Arabia’s few female sculptors. In ‘Jama’a’, a precisely-ordered group of figures in marble and resin are depicted on a marble slab in prayer, with a delicate sense of unity and common spiritual relationship, ordained by the ritual and peaceful multiplicity that is ultimately at the heart of Islamic art.

In all these works, vivid and profound statements of togetherness and the relief and common purpose of spiritual devotion coalesces into a compelling exhibition that counters the misunderstandings and misapprehensions of Islam as perceived in certain quarters of the West with intelligent, heartfelt and artistically-accomplished statements from a new generation of Saudi artistic talents.