Ahmed Mater

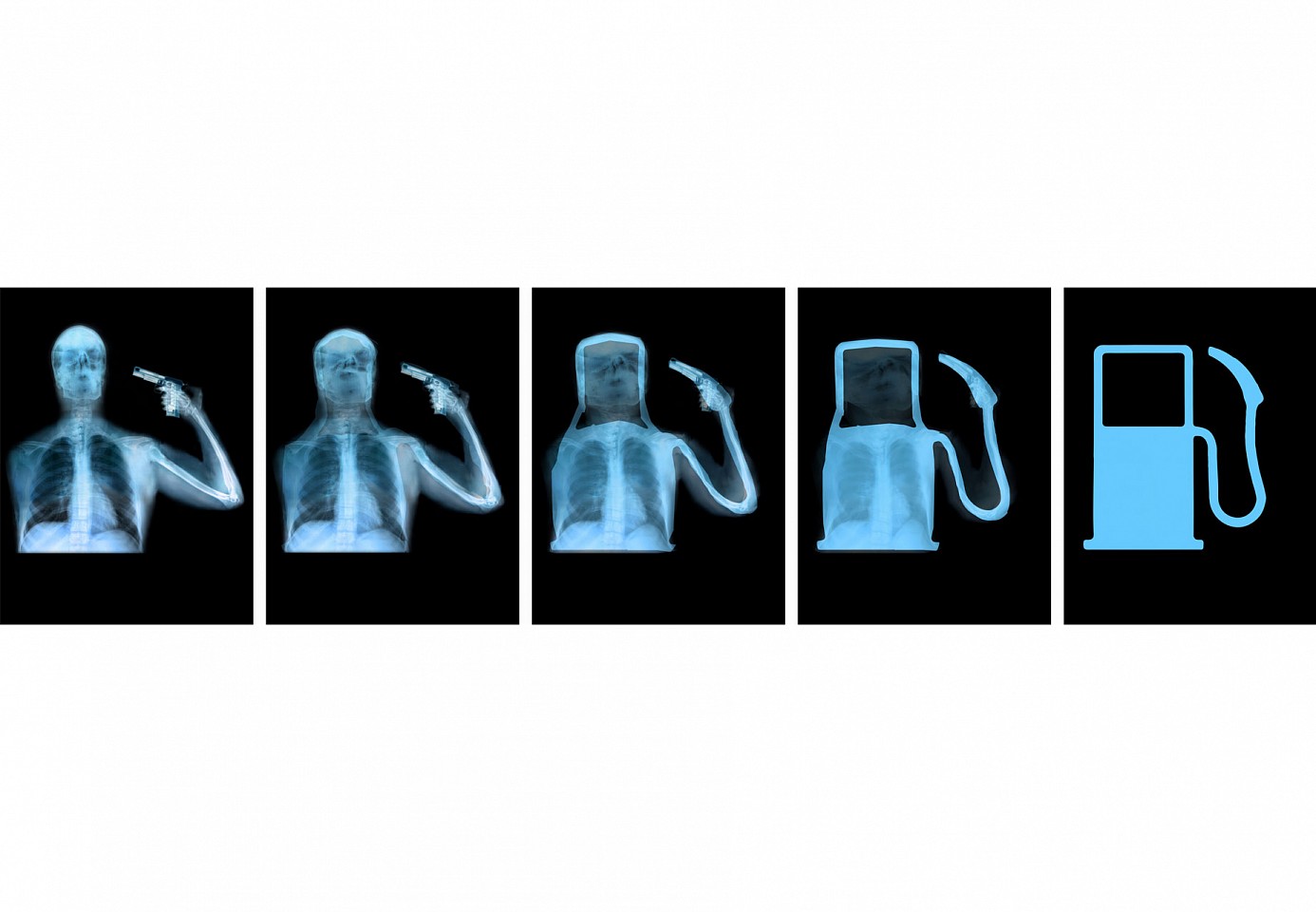

Evolution Of Man, 2010

5 silk-screen prints signed and numbered by the artist Printed with 11 colours on 400GSM Somerset Tub paper

80 x 60 cm (31 1/2 x 23 5/8 in.)

Edition of 100

AHM0000

Dana Awartani

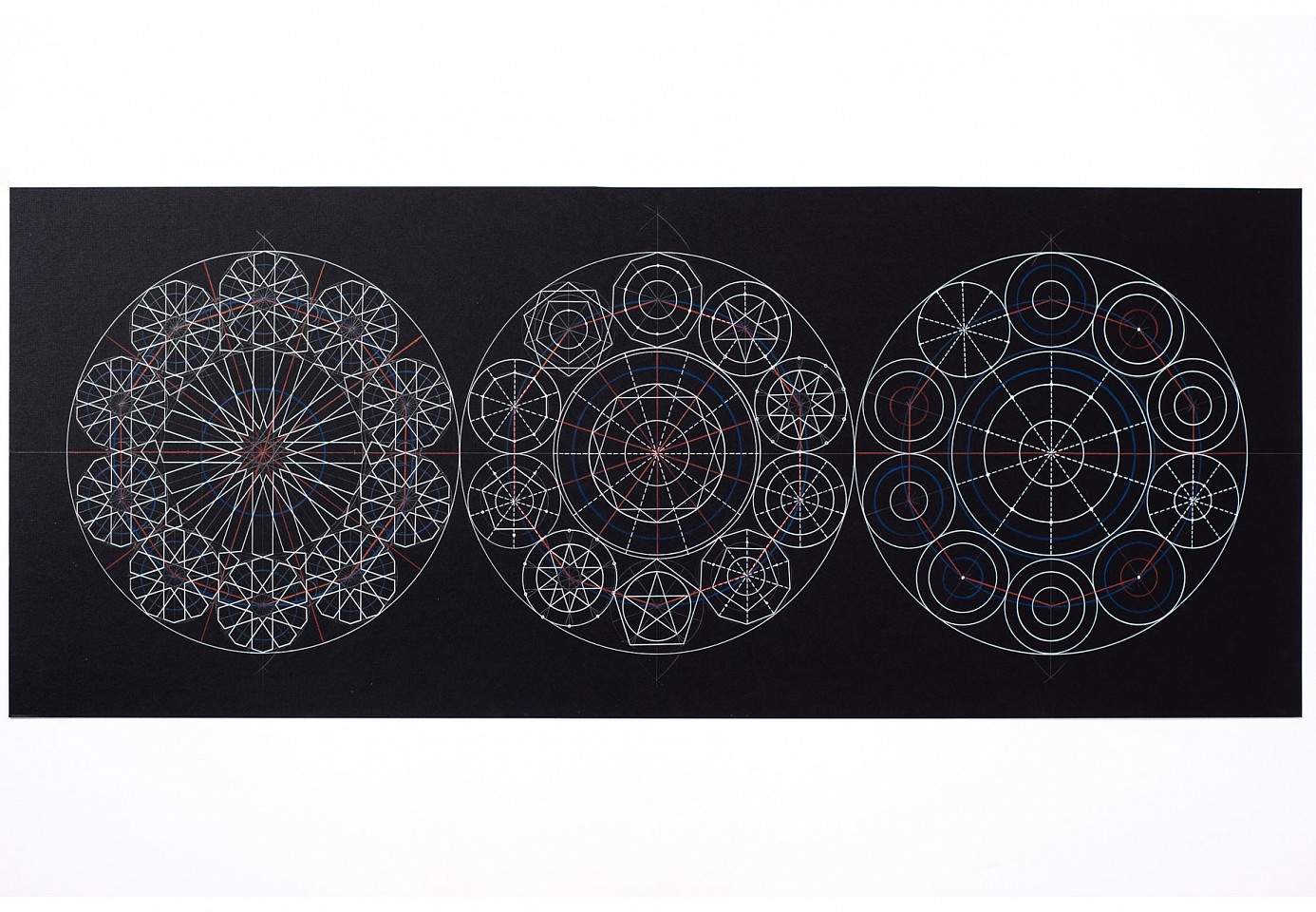

Progressional Drawing #11, 2014

Gel pen and colored pencil on paper

50 x 100 cm (19 5/8 x 39 5/16 in.)

DAN0058

Dana Awartani

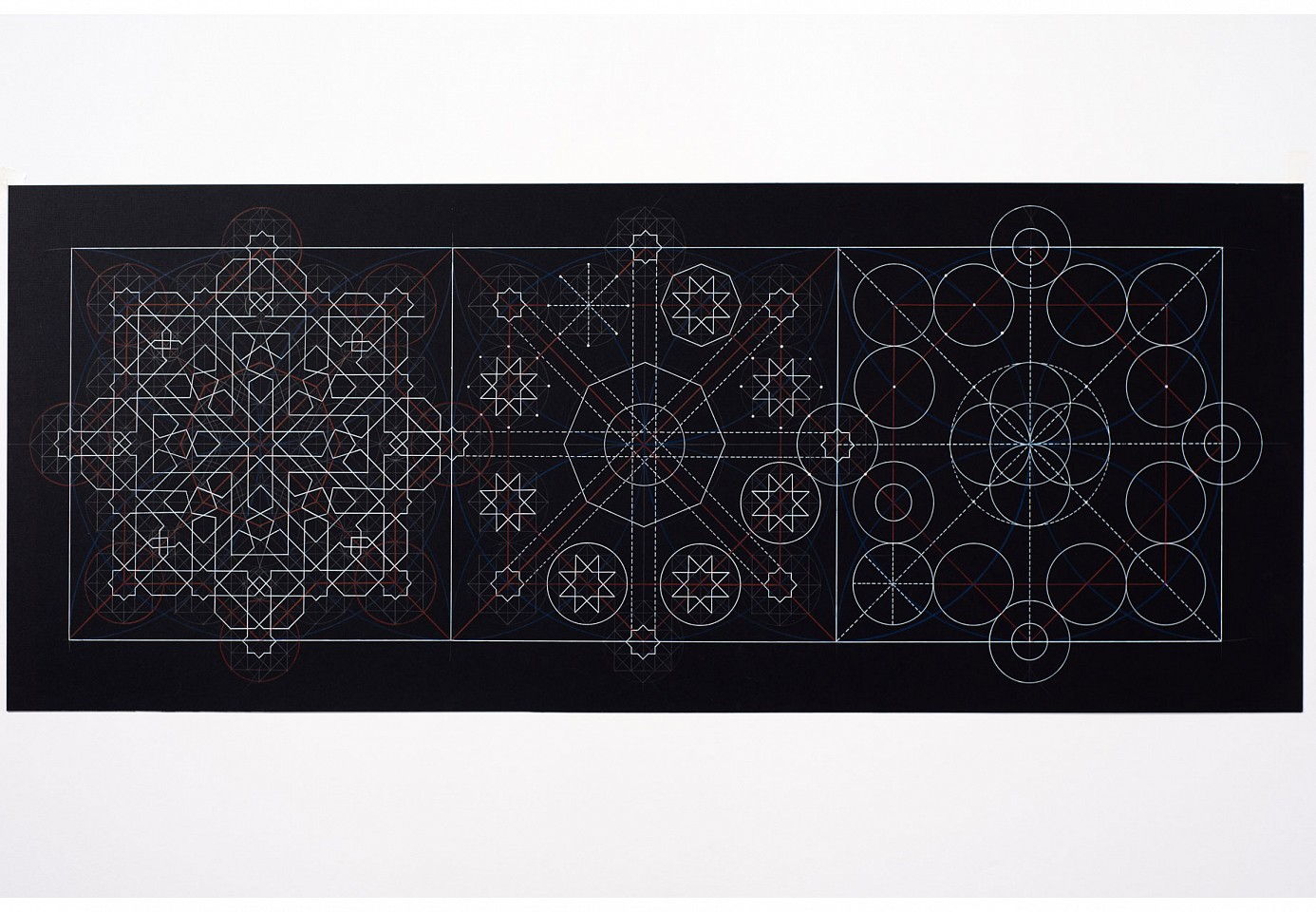

Progressional Drawing #12, 2014

Gel pen and colored pencil on paper

50 x 100 cm (19 5/8 x 39 5/16 in.)

DAN0059

Musaed Al Hulis

He Who Closely Observed People Died of Distress, 2013

Prayer Carpet and Surveillance Camera

150 x 76 cm (59 x 29 7/8 in.)

Variation of 3

MAH0020

Saudis, by and large, do not believe in the theory of evolution. Like other conservative, religious societies, Saudis have firmly rejected Darwin’s theory on the basis that human beings are perfect, state-of-the-art creations, not the result of some natural process. Ahmed Mater is a doctor by training. He believes in evolution. But for him, evolution does not necessarily mean survival of the fittest. Sometimes, evolution can lead to one’s demise. Saudi Arabia, founded in 1932, was a poor country with scarce natural resources. Then in 1938 oil was discovered in its deserts, and ten years later production was up to full capacity. Petrodollars flooded the Kingdom, transforming the face of its land and giving Saudi a great deal of leverage with the international community. Interestingly, the origin of oil is connected to the theory of evolution. Oil is derived from ancient organic matter; the remains of creatures that have not survived the planet’s biological and geological changes. Saudi Arabia did not only use petrodollars to fuel its rapid development; vast amounts of the same money were also used to promote and spread the Saudi conservative interpretation of Islam, also known as Wahhabism. But most Saudis reject this term because they believe they are simply practicing Islam in its purest form, and also because they think the term has been used unfairly to slander their religion and their country. Whether they agree with the term or not probably matters little now, because some of the ideas that originated in Saudi have, in recent years, come to shake the world. Most people will read Evolution of Man as an unabashed critique of humanity’s dependence on oil, and what ‘black gold’ represents to those living above the reserves. But Evolution of Man is more than just a political statement. As Ahmed Mater explains,

“I am a doctor and confront life and death every day, and I am a country man and at the same time. I am the son of this strange, scary oil civilization. In ten years our lives changed completely. For me it is a drastic change that I experience every day.”

Athr Gallery is proud to be taking part for the third year in the 2014 edition of Artissima International Contemporary Art Fair. Taking place at Oval Lingotto Fiere in Torino, the fair is characterised by its commitment to both commercial and more experimental presentations. In turn, Athr Gallery is committed to supporting cross-cultural dialogue and cultivating discourse towards defining a collective voice for contemporary art coming from the Middle East, and Saudi Arabia in particular. As one of the only galleries from the region to be involved in Artissima, the artists selected are representative of the diversity of work coming from the Middle East. As a collection, the Athr Gallery presentation touches on a range of subject matter and a variety of mediums, from photography and print to sculpture and appropriated matter. They are brought together by their shared preoccupations, concepts born of a time of rapid change, development and conflict. They also present a common contemplation on the interpretation of Islamic culture and ritual in the modern world, with works that look as much to Saudi’s recent history, as to the threads of early tradition and heritage innate to the visual language of Islamic art.

Saudi artist Ahmed Mater shows an iconic work, Evolution of Man (2010) – a petrol pump transforms to a man holding a gun to his head across the space of 5 silkscreen prints – here Mater questions to rapid social evolution of Saudi since the discovery of oil in 1938.

Hazem Harb is a Palestinian artist currently living between Italy and the UAE. Presented at Artissima is a recent sculptural work, We Used to Fly on Water (2014), part of his Invisible Travels series, a response to conditions of living in the Gaza Strip, where tunnels linking the area to Egypt are not only commonplace, paved with danger and uncertainty, but also essential and desperate measures against the inhumane isolation of a people.

Also Palestinian, Ayman Yossri Daydban’s work looks towards the fragmented identity of his people and his own sense of loss, appropriating commonly found materials that are regionally specific such as prayer carpets and surveillance cameras.

Recent works by Musaed Al Hulis, using found material, comment on corruption and ideological distortion within social infrastructures in Saudi Arabia.

Dana Awartani’s Progressional Drawings, take the concept of Tawhid, the Islamic teaching of the Oneness of God, taking a circle as her starting point she uses geometry as a means to reflect our understanding of the universe.

Seçkin Pirim exhibits sculptures and works on paper that examine our understanding of singularity. The works are composed of layers of sterile and simplified abstract forms, removed from any natural or organic references, they become reliant on the chain relationship between one basic modular unit linked to another, questioning notions of singularity.