At Diriyah Biennale, Chinese History Meets a Saudi Future

January 12, 2022 - Stephanie Bailey for Ocula

There were discussions about Saudi Arabia's first contemporary art biennial happening in tandem with a China-Saudi cultural year, so I was told by artist and prince Sultan bin Fahad bin Nasser. Hence the selection of Philip Tinari as artistic director.

While Covid-19 scuppered these plans, a soft power logic infuses the Diriyah Biennale (11 December 2021–11 March 2022), staged across six renovated warehouses in the JAX district of Diriyah, on the edge of Riyadh, where the UNESCO world heritage site At-Turaif constitutes the birthplace of the first Saudi state.

Hmoud Al Attawi, Al Nourhah Pillars (2021). Photo: the author.

Bringing together works by 64 artists and collectives, among whom 27 are Saudi and 13 Chinese, Tinari has organised a nuanced show with Jeddah-based curator Wejdan Reda and UCCA curators Luan Shixuan and Neil Zhang.

The exhibition's title, Feeling the Stones, creates a relational cartography between two loaded temporalities: the decades defining China's economic miracle in the late-20th century, and Saudi Arabia's 21st-century future outlined in the ambitious economic and social reform programme Vision 2030.

Filwa Nazer, H. A. (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

The phrase 'Crossing the river by feeling the stones' characterised China's period of reform and opening launched in 1978, which ushered dynamic economic and sociopolitical transformations as citizens began testing the limits of artistic and political expression.

Historical trajectories from which this moment departed are found in the first of six thematic sections, which Tinari describes as the curatorial brain in reference to Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev's documenta 13.

Zheng Yuan, The Last Step of Touchdown (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Photo: the author.

Zheng Yuan's three-channel video The Last Step of Touchdown (2021) explores 20th-century Cold War politics through technology transfers between China and the Soviet Union, and later the United States, pinned to footage of politicians disembarking from planes.

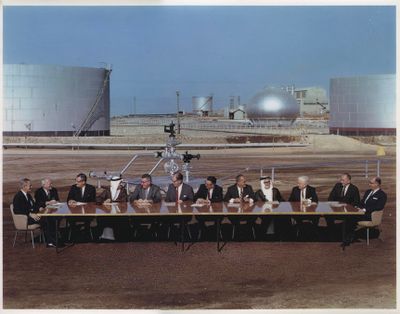

Ahmed Mater's Desert Meeting (2021) extends this historical purview, with five cathode-ray televisions screen motion images representing the rise of Saudi Arabia's oil economy.

Ahmed Mater's Desert Meeting (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

One image shows Aramco's annual board of directors meeting in front of Dammam Well No. 7, the first to produce commercial yields in 1938.

The year is 1962, two years after OPEC (Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries) was established, which excluded America and Russia, and six before OAPEC (Organisation of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries) was founded in 1968—a harbinger of the 1973 oil crisis, an embargo initiated by OAPEC in retaliation against the Arab-Israeli War, and Aramco's full nationalisation in 1980.

Ahmed Mater, 'Desert Meeting' (2021) (still). Motion photographs on cathode-ray TVs. Artist proof edition. 130 x 60 x 43 cm. Courtesy Lakum Artspace and the artist.

Ibrahim El Dessouki's pentaptych 'Gated Communities' series (2020) departs from the 1980s, with oil paintings capturing distilled moments that characterise Egypt's gated suburban 'compound culture' whose development is tied to socioeconomic inequalities driven by neoliberal policies. In one, two men sit in the foreground wearing a uniform of white shirt and jeans, as a barrier forms a line over their heads.

Ibrahim El Dessouki, 'Gated Communities' (2020). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

William Kentridge, More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Bleeding into this section is music by the African Immanuel Essemblies Brass Band accompanying William Kentridge's More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015). Walking across eight screens is a looping procession of archetypal figures depicted as near-shadows, among them clergymen, miners, and an armed ballet dancer dressed as a red-capped revolutionary.

Left to right: Sarah Abu Abdallah and Ghada Alhassan, Horizontal Dimensions (2021); Birdhead, Birdhead World (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Through these characters, Kentridge speaks to the notion of 'peripheral thinking', the title of the show's third section where Sarah Abu Abdallah and Ghada Alhassan's Horizontal Dimensions (2021)—a curved, 25-metre landscape of collaged elements (like tarot cards and bat photos) on an earth-washed canvas—converses with a wall of black-and-white photographs depicting the streets of Shanghai by Birdhead.

Wang Luyan, 'Corresponding Non-correspondence' series (2010–2019). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Photo: the author.

Kentridge introduced peripheral thinking in a 2016 lecture, describing 'the act of seeing (and thinking)' as 'a negotiation between what comes towards us and what we project onto it'.1

That equation connects with those visualised in Wang Luyan's figurative wood and metal sculptures from the 'Corresponding Non-correspondence' series (2010–2019), which take up one room in the first section.

Wang Luyan, 'Corresponding Non-correspondence' series (2010–2019). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

A member of the Stars group in China, who challenged the state's monopoly on art in 1979 by hanging their works on the gates of the National Museum of Art in Beijing, Wang co-founded the New Measurement Group in 1988, which disbanded in 1995. He later retreated from public practice as he designed his diagrammatic compositions.

In Persons Facing Away and Towards D17 (2017), two people sitting on chairs face away from each other, their heads becoming the point from which an inversion arises. While the title for two metal figures placed side by side on a wooden plinth speaks to the embodied paradox that Wang's figures raise: Two People Who Walk Along the Right/Left Side While Walking Towards/Away from Each Other (2011).

Bricklab and Mammafotogramma, Through the Looking Glass (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Photo: the author.

These three-dimensional diagrams visualise the logic infusing the Biennale's title. In a world where one person's right is another person's left, questions not answers, the artist proposes, are what shape reality. Hence, feeling the stones, a metaphor for staying close to the material conditions in the face of projected views so as to grasp what is at hand.

Wang's bodily equations extend to the context in Through the Looking Glass (2021), a collaboration between Bricklab, the Jeddah-based architectural firm that designed the exhibition, and the Milanese studio Mammafotogramma.

Bricklab and Mammafotogramma, Through the Looking Glass (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Photo: the author.

In front of a large window looking out to the Wadi Hanifa valley and the construction taking place along it, a series of Murano glass lenses hang from a steel frame to augment the world outside into fluid warps.

'While development in Diriyah constitutes one of the tourist-driven giga projects underway in the KSA, it revolves around a context-specific heritage.'

These dramatic sightlines are amplified by Superstudio's prints on an opposing wall, from the conceptual project Continuous Monument: An Architectural Model for Total Urbanisation (1969–1979). Conceived as 'a single piece of architecture to be extended over the whole world', one image shows Manhattan cut through with a white structure that stretches into the horizon like a road.

Superstudio, Continuous Monument: An Architectural Model for Total Urbanisation (1969–1979). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

According to studio member Adolfo Natalini, these images were conceived as a 'warning of the horrors architecture had in store with its scientific methods for perpetuating standard models worldwide.'

With that in mind, Through the Looking Glass both contends with and extends Continuous Monument's view. While development in Diriyah constitutes one of the tourist-driven giga projects underway in the KSA, it revolves around a grounded, context-specific heritage.

Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

These spatial relations, which expand Wang's paradoxical diagrams, speak to the Diriyah Biennale as an event positioned between past and future designed to showcase the opening of a closed kingdom. Perhaps this is why Tinari highlighted two works placed in conceptual juxtaposition at the show's start during a press tour.

Maha Mallah's World Map (2021) is made from 3,840 cassette tapes that transmitted what Tinari describes as 'a more conservative version of Islam than what we see now being embraced' in Saudi Arabia.

Left to right: Richard Long, Red Earth Circle (1989); Maha Mallah, World Map (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Beyond this is Richard Long's Red Earth Circle (1989), a giant mud ring splashed on a black wall that has not been restaged since its showing in Magiciens de la Terre in 1989, remembered as a watershed—if problematic—moment in global exhibition-making.

At the time, the placement of Long's work next to Yam Dreaming, a sand painting by members of the Yuendumu Aboriginal community, drew criticism—in particular from Rasheed Araeen, who participated in the show—for the flattening of difference and the re-assertion of a Western-dominated framing.2

Lei Lei and Chai Mi, 1993–1994 (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Long's work reignites the question of what it means to be global, but this time in a post-Western context, with Tinari making a concerted effort to place works by artists on an equal plane without erasing their particularities.

This premise is outlined in 'Experimental Preservation', named after architect Jorge Otero-Pailos to describe the balance between rapid modernisation and heritage conservation.

Zahra Al Ghamdi, Birth of a Place (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Here, Lei Lei and Chai Mi's two-screen video 1993–1994 (2021) offers an intimate view of globalisation through home videos made by Chai's father as a worker in the U.A.E. in the 1990s, while landscapes by Xu Bing and Zahra Al Ghamdi employ classic genres to amplify what macro-representations flatten or obscure.

Marwah AlMugait, This Sea is Mine (2021). Performance view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Positioned in the room's centre, Al Ghamdi's Birth of a Place (2021) is described as an elegy in the face of gentrification, with Diriyah's historic landscape of clay houses depicted as a dramatic series of mud peaks.

Their rising forms recall the seven earthen columns by Hmoud Al Attawi honouring the contributions of Saudi women through history on the grounds of At-Turaif as an off-site Biennale work, as well as the tan costumes worn by 12 women who performed Marwah AlMugait's subtly confrontational opening night performance This Sea is Mine (2021), which blended Palestinian, South African, and Arab chants and movements.

Xu Bing, Background Story: Streams and Mountains Without End (2014). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

In the distance, Xu Bing's monumental lightbox Background Story: Streams and Mountains Without End (2014) appears to be a landscape painting, until you go behind the frosted glass to find shadows created from cardboard, plastic, twigs, and shrubs.

Abdullah Al Othman, Manifesto: The Language & City (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

The substance behind the façade is an overarching theme in 'Going Public', which opens with Abdullah Al Othman's Manifesto: The Language & City (2021): a wall of LED, neon, lightbox, and wooden signage drawn from Riyadh's shops, cafés, and restaurants offer a vision of a city from street level.

Tavares Strachan, EIGHTEEN NINETY (2020). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Contained in its own room, Tavares Strachan's EIGHTEEN NINETY (2020) confronts historical obfuscation. Walls covered in pages from the artist's Encyclopaedia of Invisibility (2018) are printed over with patents from 1890, the year an unprecedented number of Black inventors submitted to the U.S. patent office.

Furthering the narrative of invisibility and its recuperation is Manal Al Dowayan's Tree of Guardians (2014), which presents illustrations created during various workshops with Saudi women of family trees tracing matrilineal rather than the customary patriarchal lineages, which frame a hanging installation of golden leaves.

Manal Al Dowayan, Tree of Guardians (2014). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Beyond ongoing struggles, Al Dowayan's installation reflects how far things have come. In 2014, women in Saudi Arabia were not permitted to drive or be seen in public without an abaya. This has changed.

These significant, if incremental, strides are extended by a younger generation. In 'Brave New Worlds', a captivating ten-channel projection-mapped video performance by young Saudi choreographer Sarah Brahim titled Soft Machines / Far Away Engines (2021), depicts dancers enacting the morphology of breath, at times their interaction invoking queer intimacies through measured bodily entanglements.

Sarah Brahim, Soft Machines / Far Away Engines (2021). Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

In this section, interconnections between China and Saudi Arabia are reinforced with a 21st-century lens. Simon Denny's video Real Mass Entrepreneurship (2017) captures the energy of Shenzhen's tech industry, while Lawrence Lek's video game Nøtel (Red Sea Edition) (2021) depicts a hotel whose hyper-technology echoes the aspirations of Neom, another Saudi giga project in the form of a futuristic mega-city, whose name is a Greek-Arabic portmanteau meaning 'new future'.

The exhibition title hovers like a disclaimer over works like this, with projections measured by grounded interventions.

Lawrence Lek, Nøtel (18 Third Ear Suite Enjoy Your Stay) (2016–ongoing). Multimedia installation, VR experience, open-world game. Duration variable. Exhibition view: Feeling the Stones, Diriyah Biennale, Riyadh (11 December 2021–11 March 2022). Photo: the author.

Take Ayman Zedani's intriguing installation Between Desert Seas (2021), a mound of salt surrounded by speakers emitting sounds of Arabian Sea humpback whales and interviews with those involved in their conservation. We learn about the species' unique evolution; separated from other humpbacks some 70,000 years ago, they developed their own unique culture.

As with humans, differences exist and context is key. To feel those textures, to go from your here to their elsewhere, you have to be open to it. It's a clever point that works for art criticism as it does for tourism and diplomacy. —[O]

1 Iwona and Sabine Breitwieser (eds), William Kentridge: Thick Time, Accessed 22 December 2021, https://www.kentridge.studio/peripheral-thinking-2/.

2 'Thirty years ago a show in Paris set out to redraw the art world', The Economist, 4 May 2019, Accessed 22 December 2021, https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2019/05/02/thirty-years-ago-a-show-in-paris-set-out-to-redraw-the-art-world.

Back to News