Ayman Yossri Daydban

Ayman Yossri Daydban

The Opening 8 PCS, 2010

RC Print Diasec mounted on Dibond

26 x 46.5 cm (10 1/4 x 18 1/4 in.)

From the series Subtitles, Edition Size: 3 + 1 AP

AYD0250

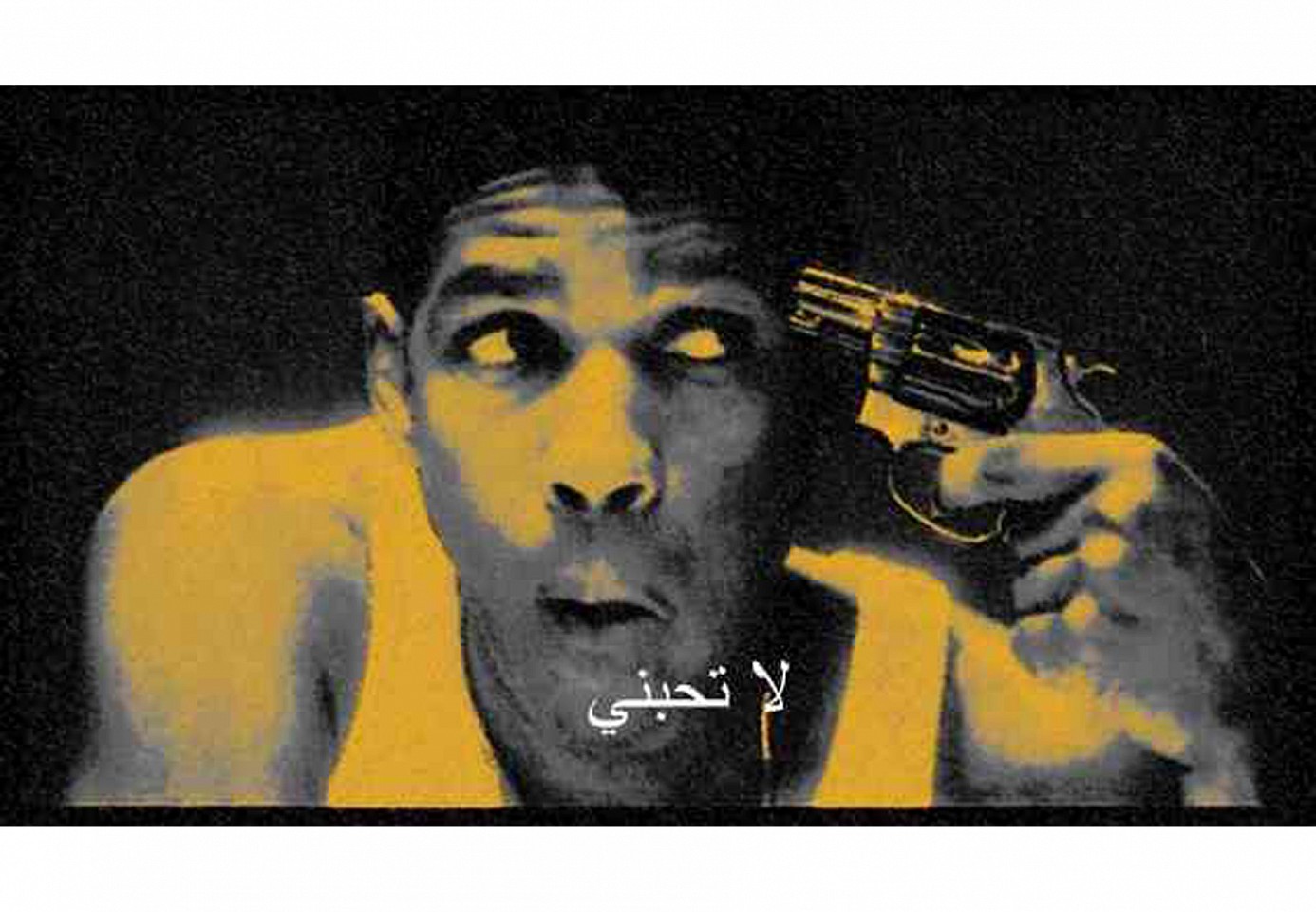

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Thuma Tatawar El Amr, 2009

RC Print Diasec mounted on Dibond

71 x 102 cm (28 x 40 1/8 in.)

From the series Subtitles, Edition of 3 + 1 AP

AYD0175

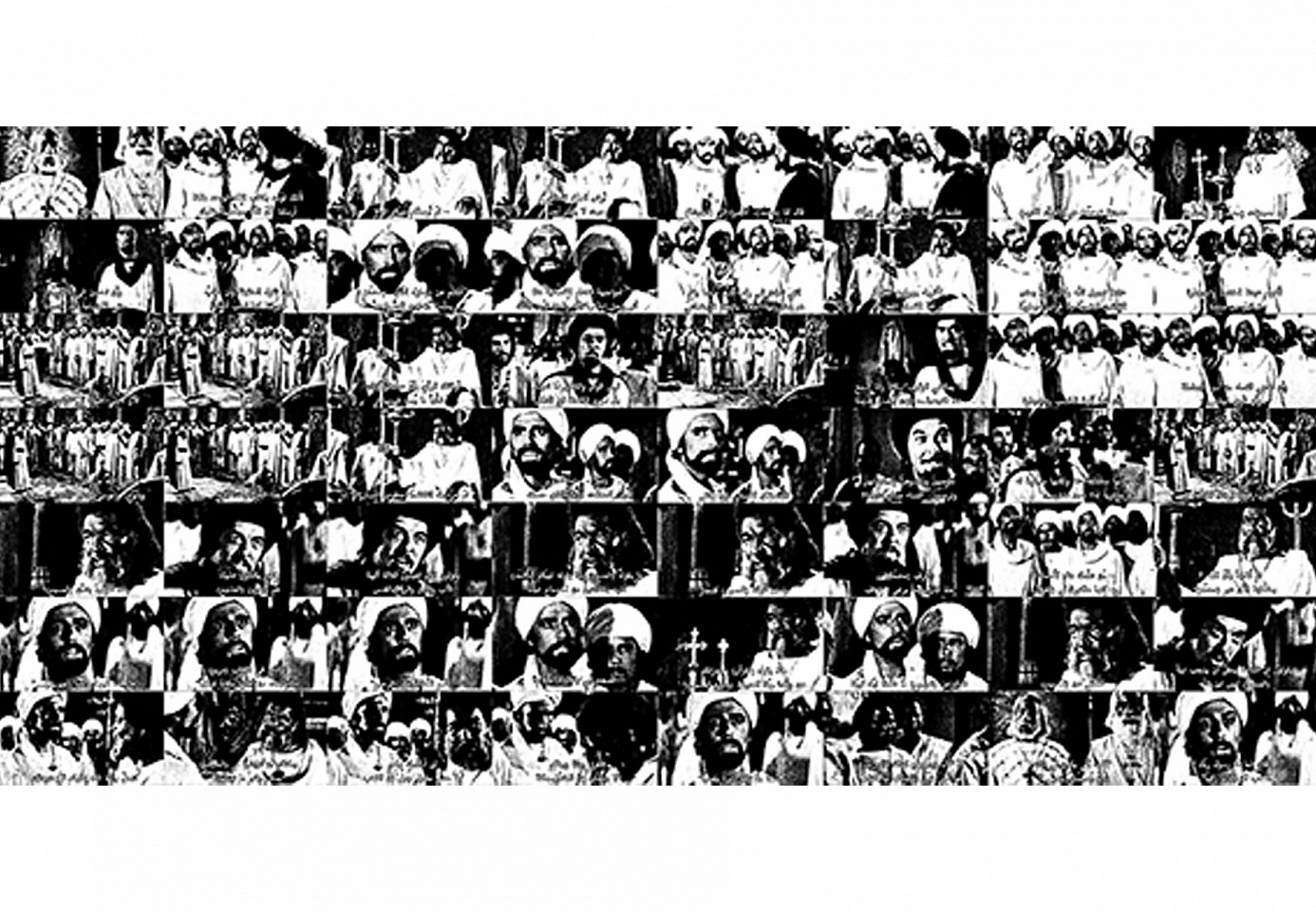

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Abeed Al Manazil [The House Negro], 2011

Fujicolor Crystal Archive Print

26 x 51 cm each; 8 pieces

From the Subtitle series Edition of 3 + 1 AP

AYD0315

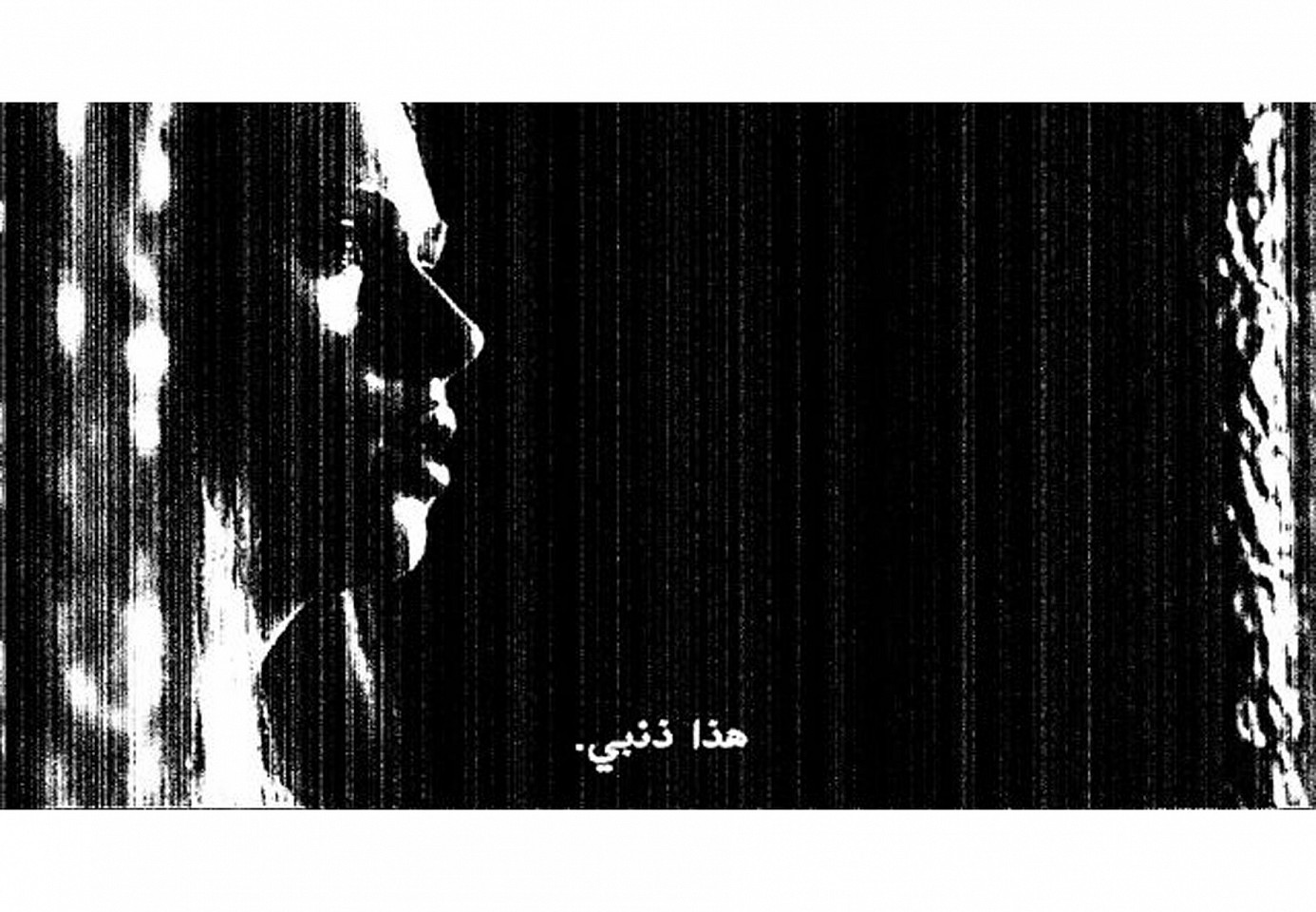

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Hatha Thanbi, 2010

RC Print Diasec mounted on Dibond

53 x 93 cm (20 7/8 x 36 5/8 in.)

From the series Subtitles Edition of 3 + 1 AP

AYD0287

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Oohh, 2009

C-Type mounted on Aluminum

42 x 72 cm (16 1/2 x 28 3/8 in.)

From the series Subtitles Edition Size: 3 + 1 AP

AYD0190

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Love Me, Love Me Not, 2010

Lenticular Imaging

62 x 110 cm (24 3/8 x 43 1/4 in.)

From the series Subtitles Edition of 3 + 1 AP

AYD0230

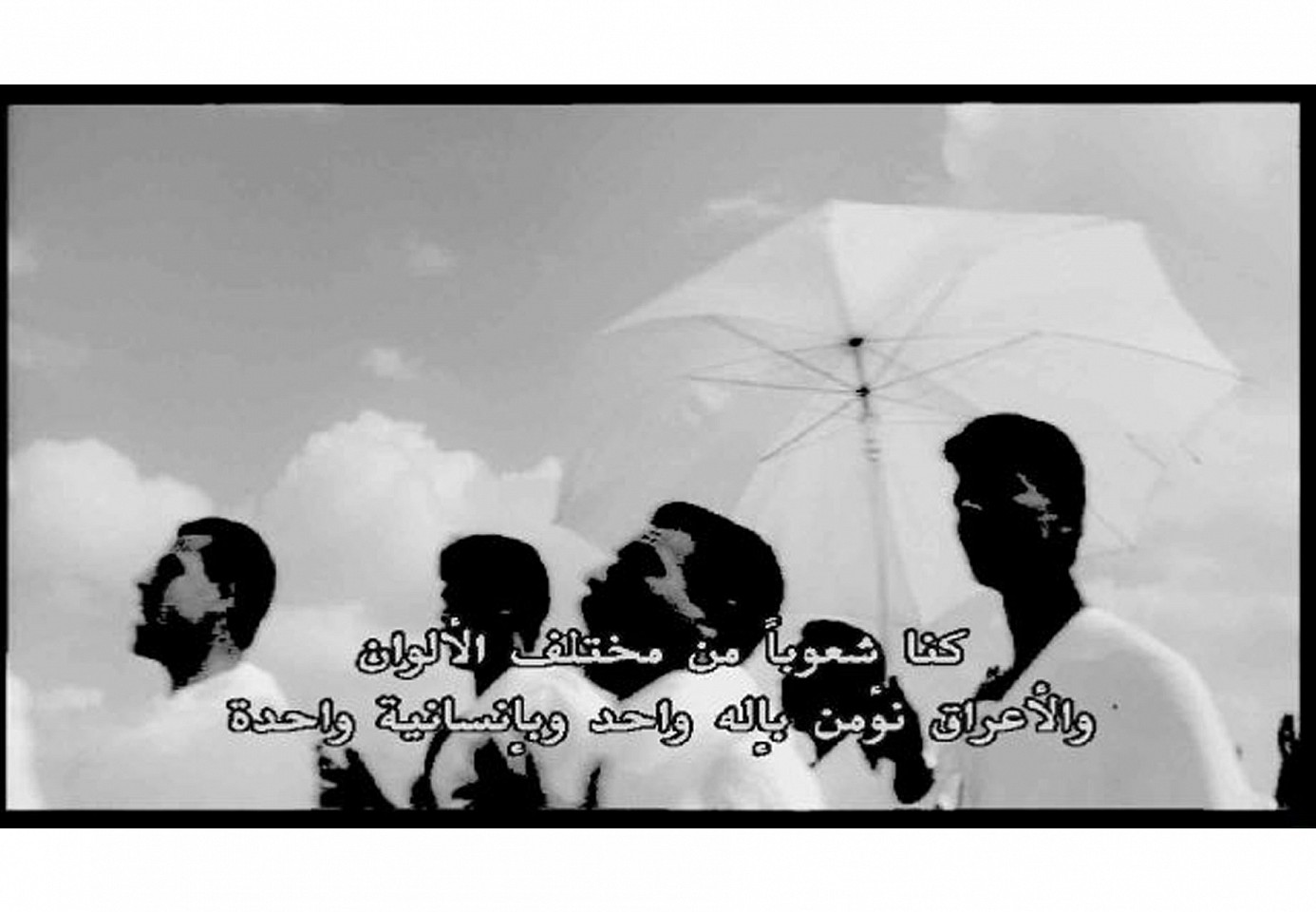

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Kunna Sho'oban, 2010

Lightbox

87 x 155 cm (34 1/4 x 61 in.)

From Subtitles series, Edition of 3+1 AP, Acquired by The British Museum, London

AYD0311

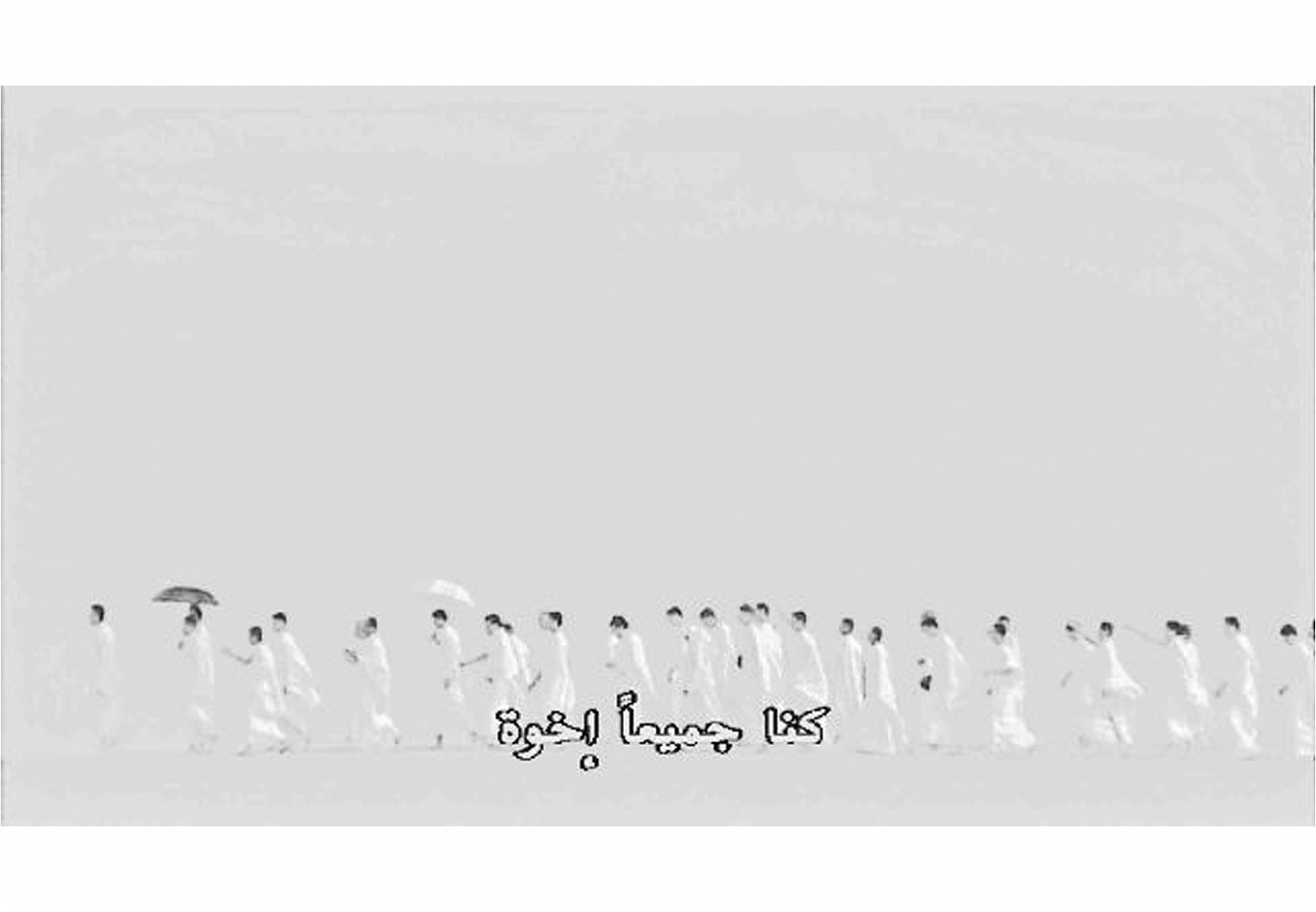

Ayman Yossri Daydban

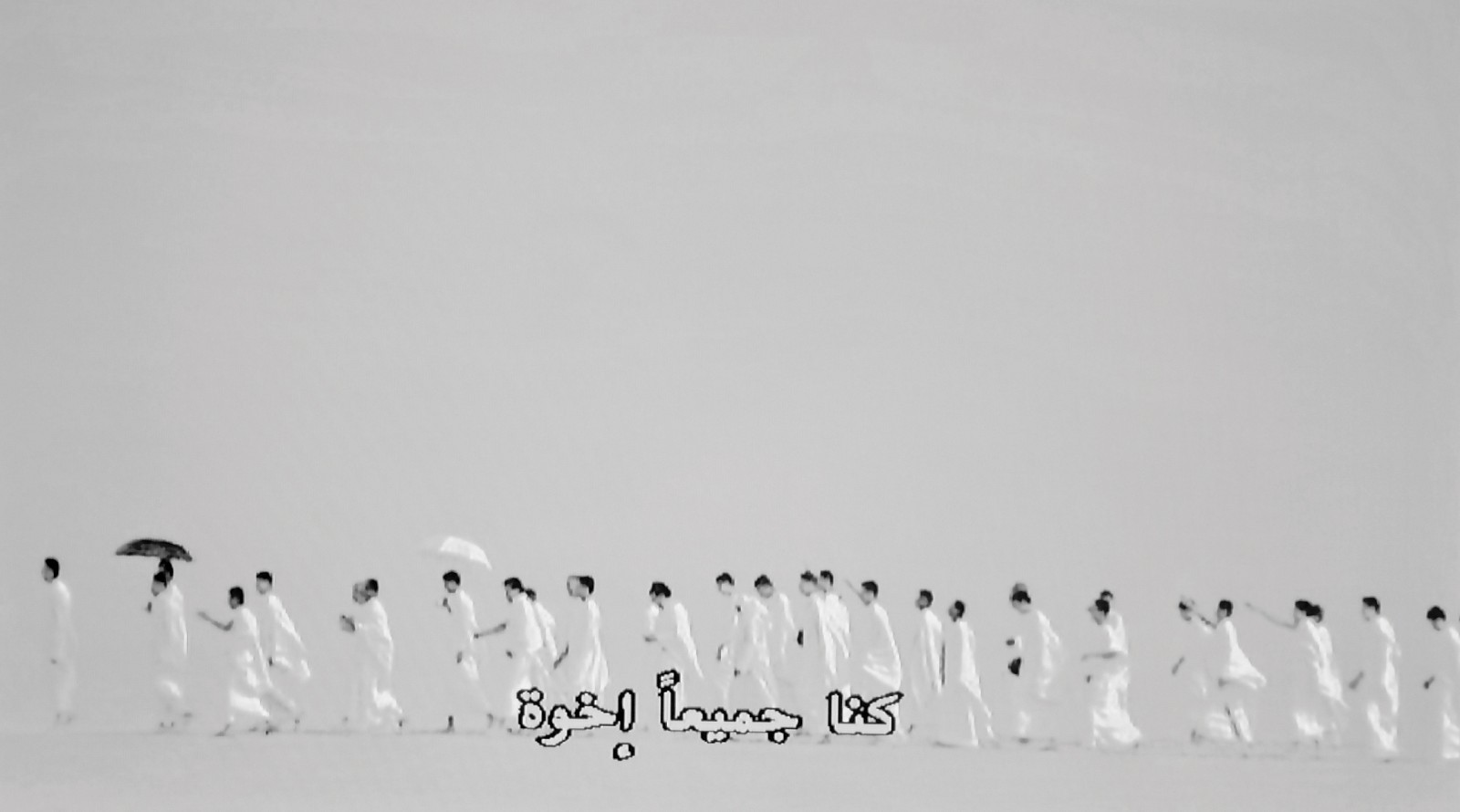

Kunna Jameean Ekhwa, 2010

Lightbox

87 x 155 cm (34 1/4 x 61 in.)

From Subtitles series, Edition of 3+1 AP, Acquired by The British Museum, London

AYD0298

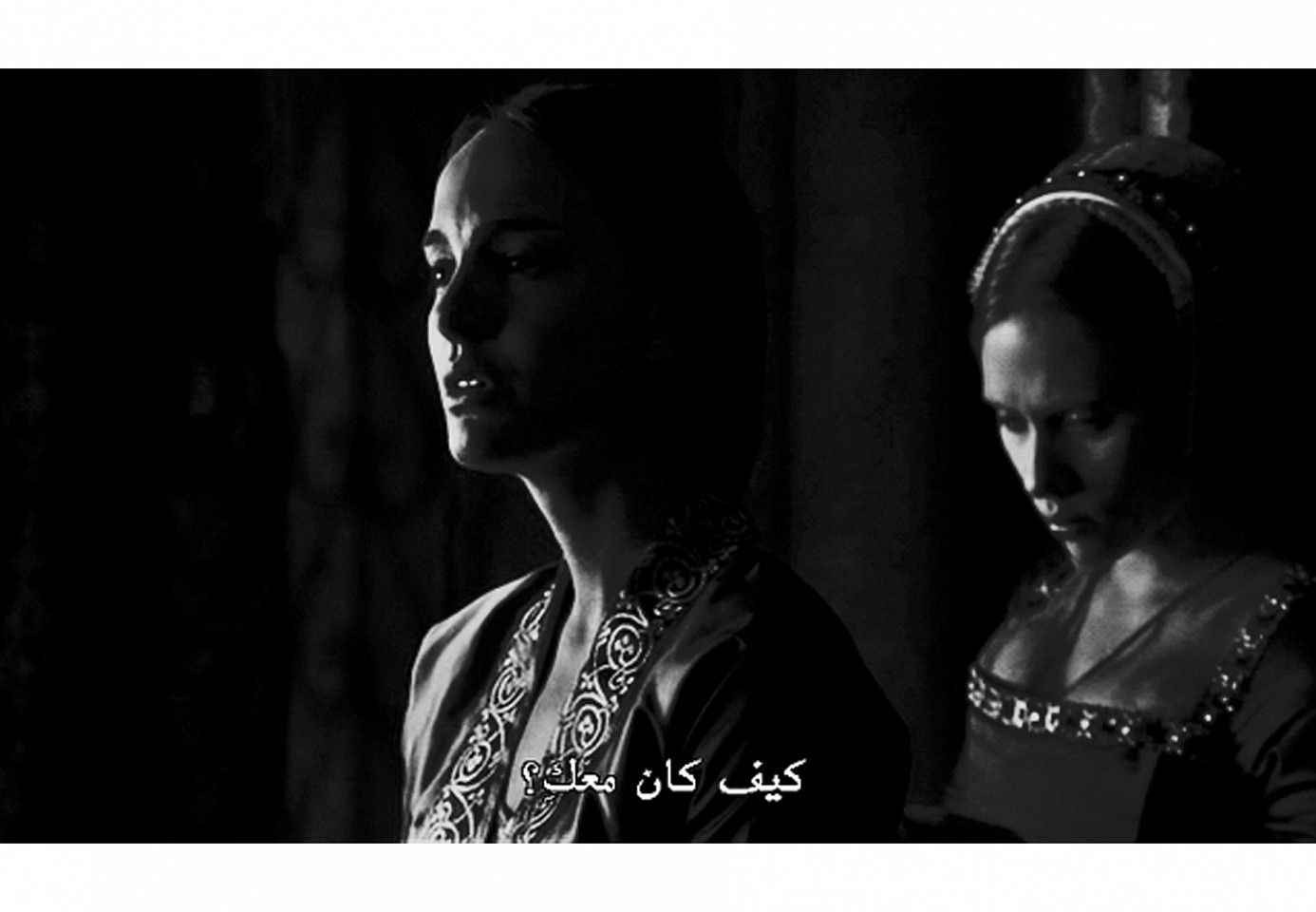

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Kayfa Kana Ma'aki, 2010

C-Type mounted on Aluminum

42 x 72 cm (16 1/2 x 28 3/8 in.)

From the series Subtitles Edition of 5 + 1 AP

AYD0261

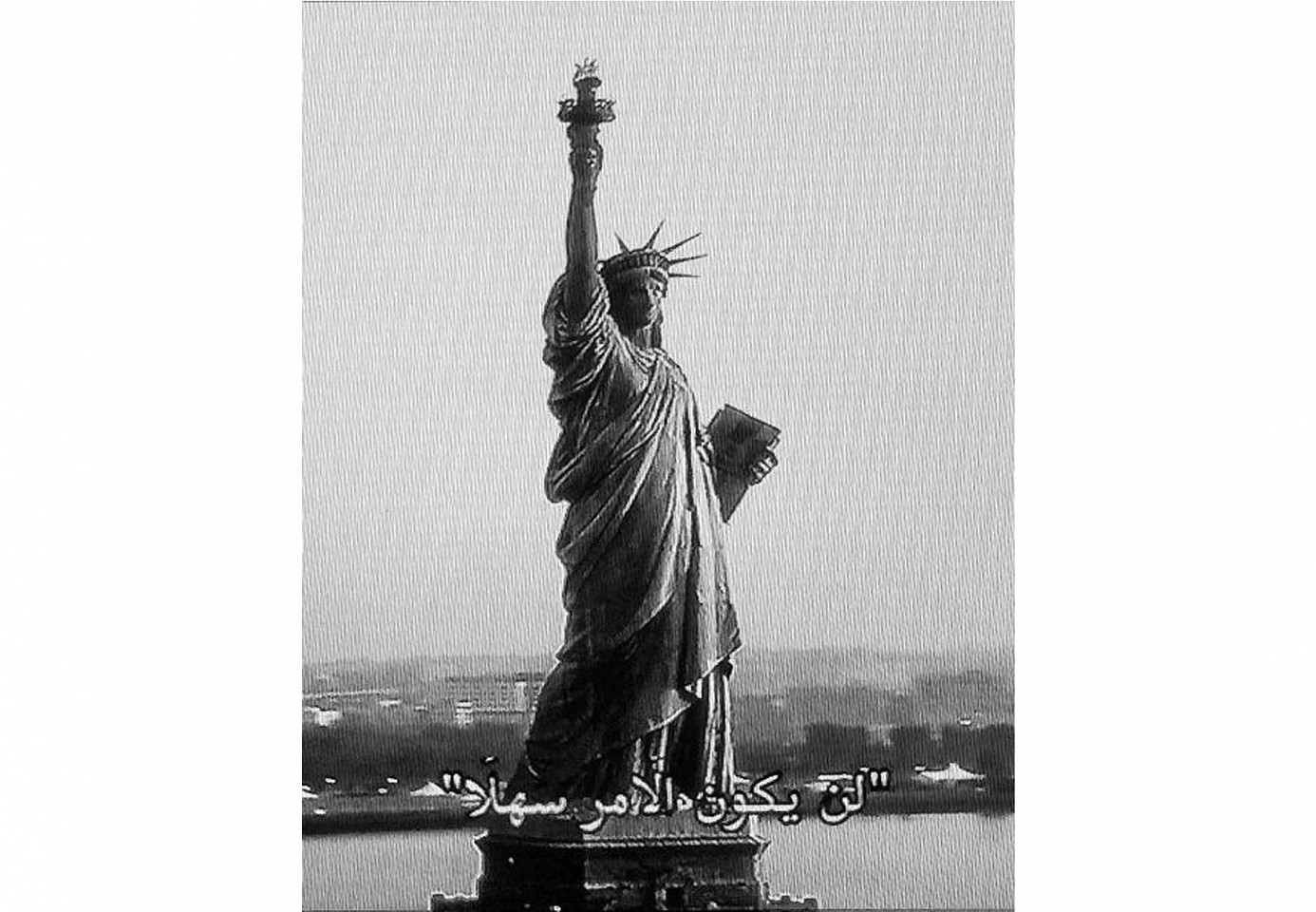

Ayman Yossri Daydban

It Will Not Be An Easy Matter, 2012

Photographic Print on Archival Paper

62 x 110 cm (24 3/8 x 43 1/4 in.)

From Subtitle series, Edition of 3

AYD0321

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Abyssinia, 2012

Metallic lambda print mounted on dibond

210 x 146 cm (82 5/8 x 57 1/2 in.)

From the sub-series Dialogues of Subtitles series, Variation 2

AYD0405

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Salahuddin, 2010

Mixed Media on Canvas

200 x 200 cm (78 3/4 x 78 3/4 in.)

From the series 'Asmaa'

AYD0324

Ayman Yossri Daydban

The Bell, 2012

Stainless steel

AYD0404

Ayman Yossri Daydban

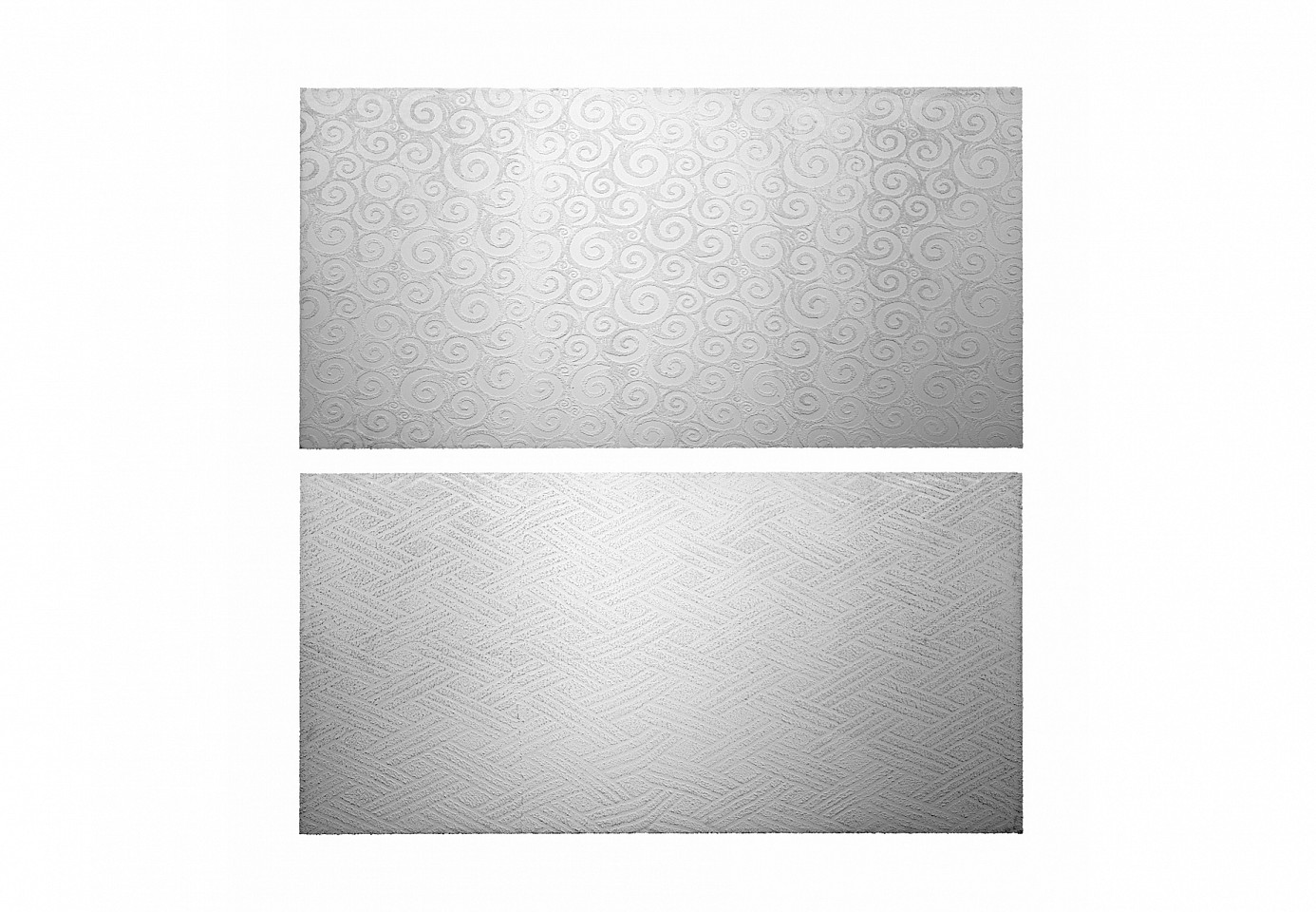

Ra'i from Ihramat, 2012

Stretched Ihram Fabric over Wooden Frame

240 x 480 cm (94 1/2 x 189 in.)

AYD0396

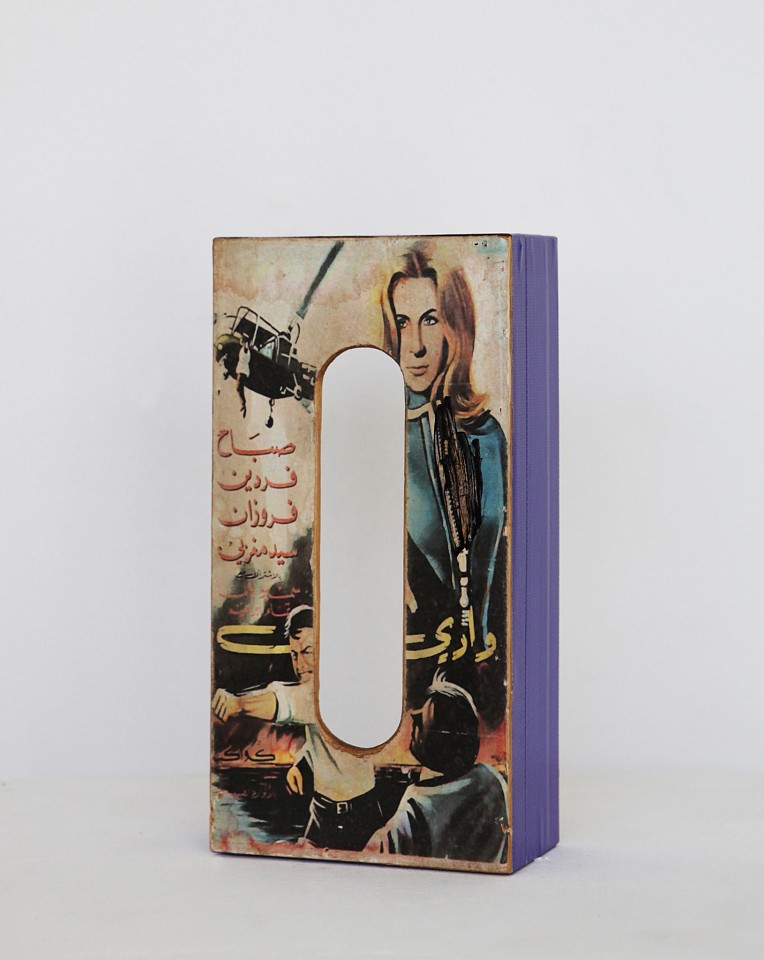

Ayman Yossri Daydban

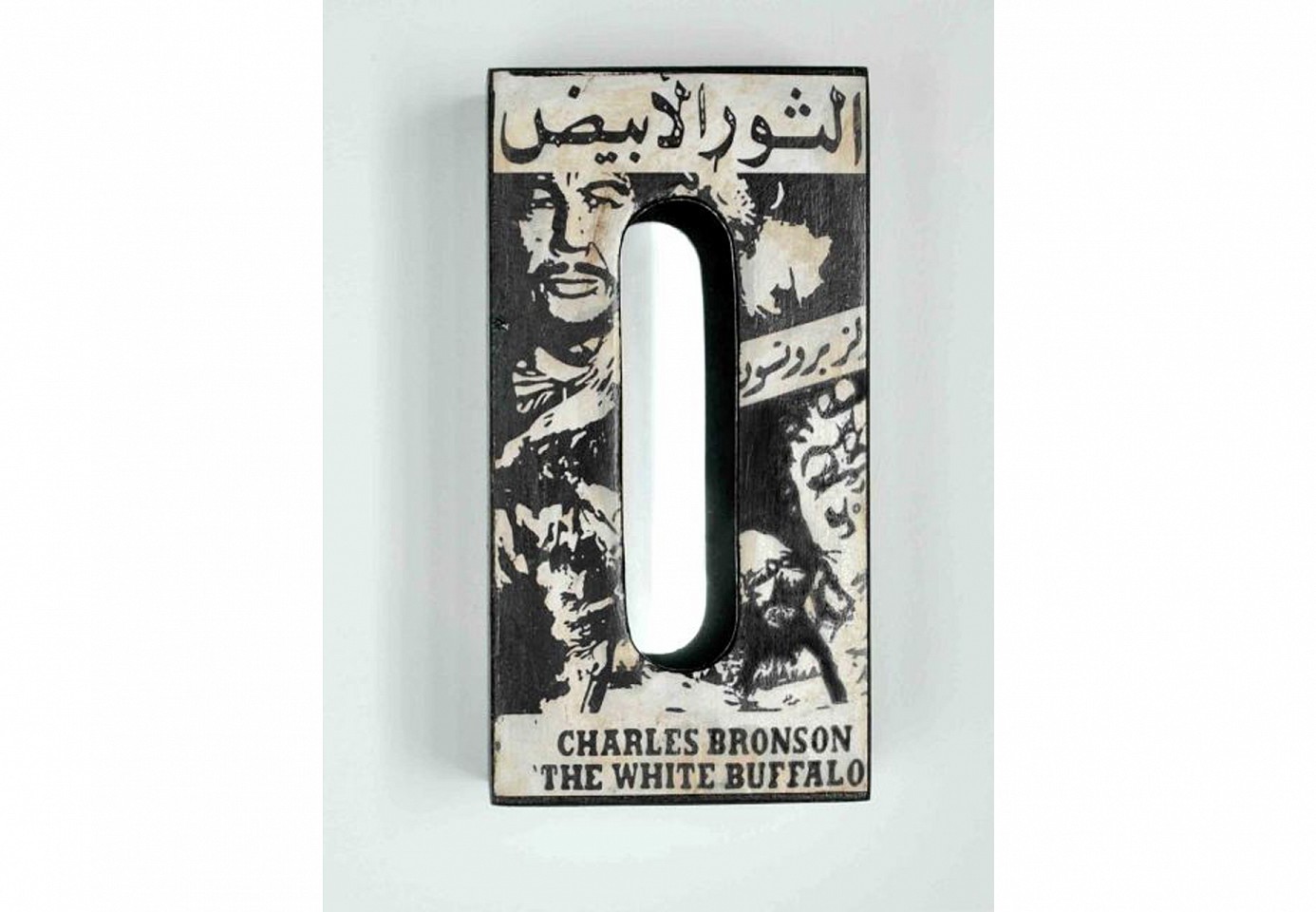

White Buffalo from the seires 'Maharem', 2010

B&W Print on Wooden Tissue Box

104 x 270 cm (41 x 106 1/4 in.)

3

AYD0340

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Pepsi, 2011

100% Cotton Acid Free Paper

77 x 56 cm (30 3/8 x 22 in.)

AYD0422

Ayman Yossri Daydban

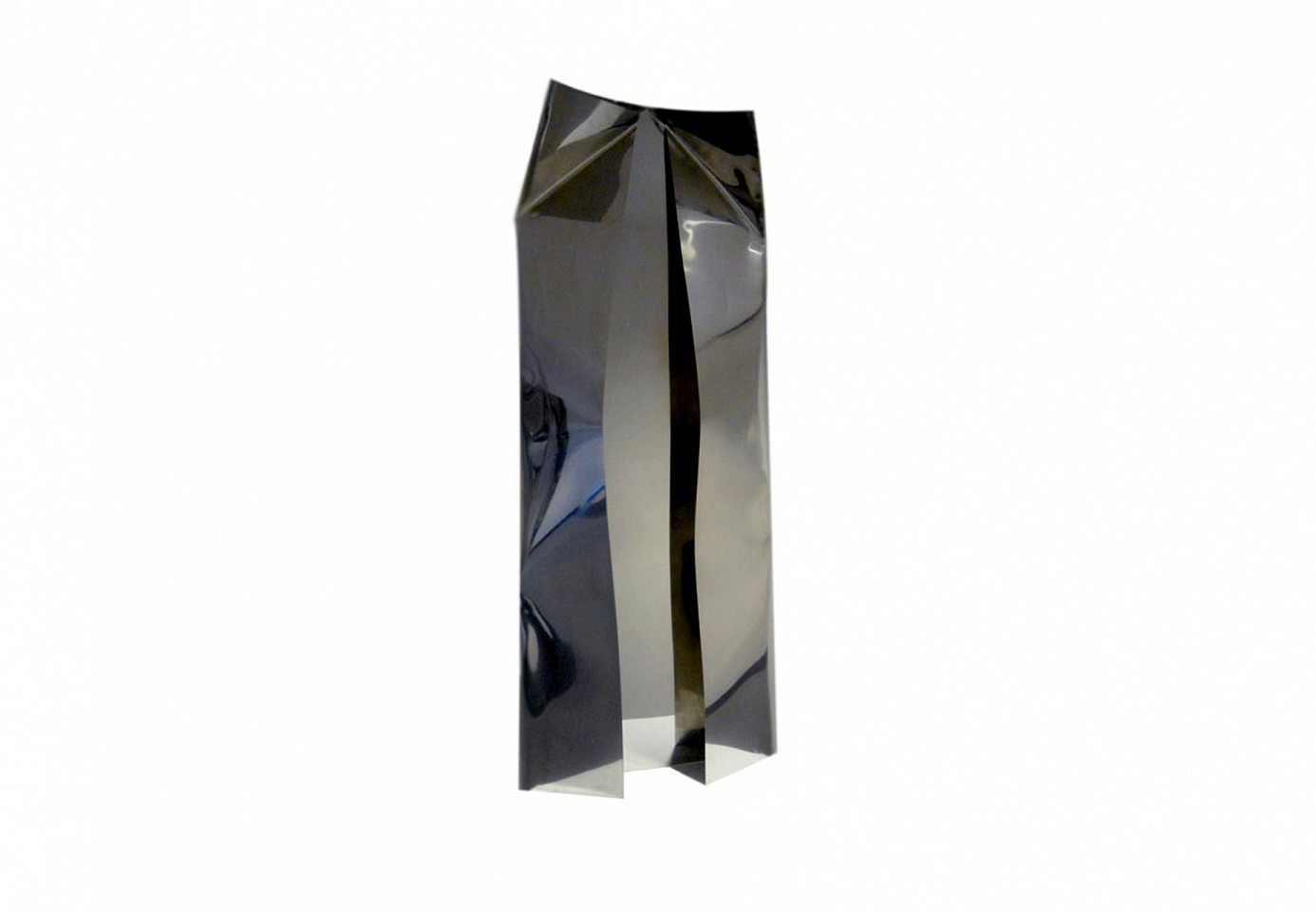

Distortion 03, 2011

Stainless steel

139 x 49 cm (54 3/4 x 19 1/4 in.)

AYD0435

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Distortion 04, 2011

Stainless steel

135 x 42 cm (53 1/8 x 16 1/2 in.)

AYD0436

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Reflections 06, 2011

Stainless steel

206 x 41.5 cm (81 1/8 x 16 3/8 in.)

AYD0443

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Reflections 16, 2012

Stainless steel

220 x 61 cm (86 5/8 x 24 in.)

AYD0448

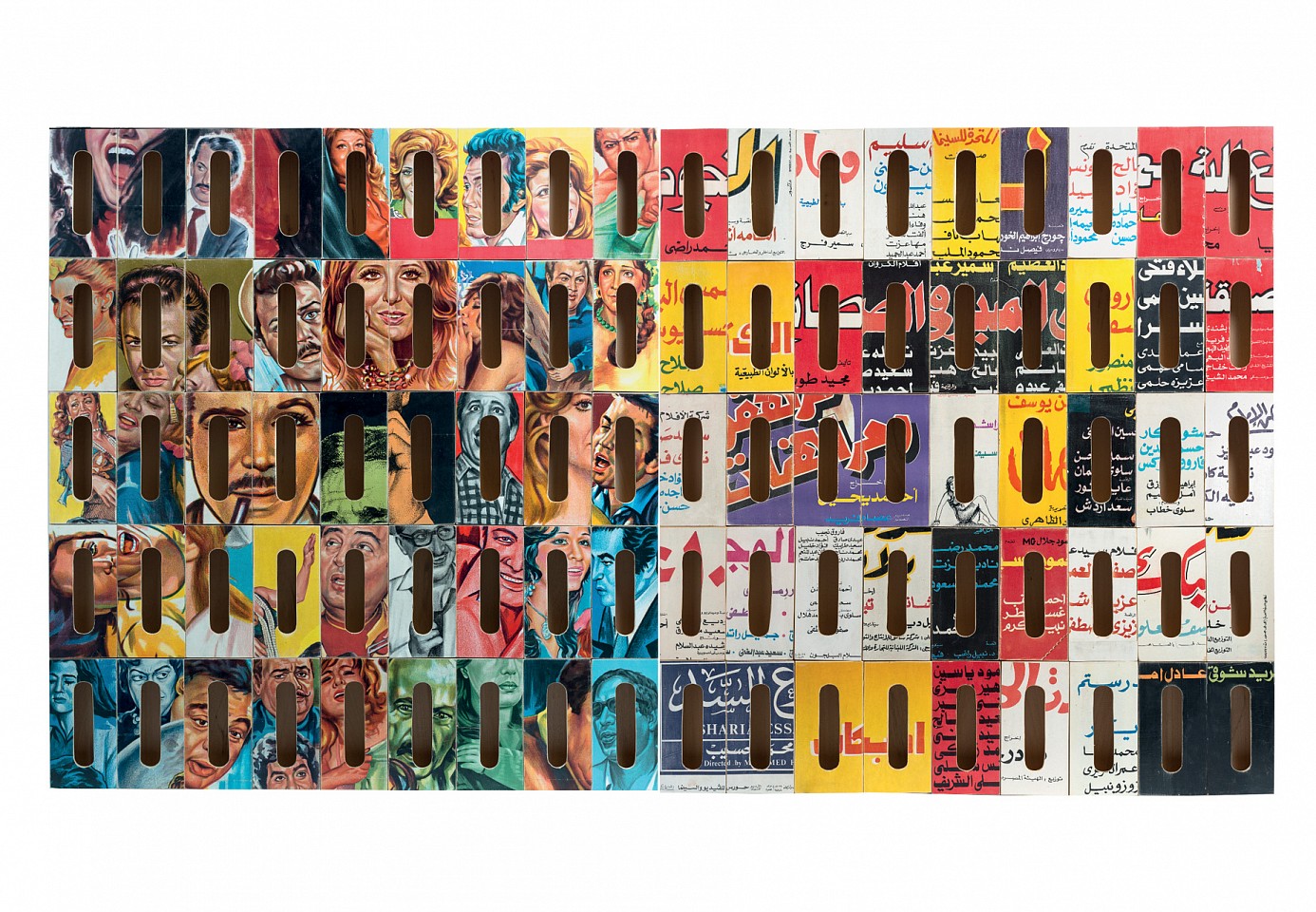

Ayman Yossri Daydban

White Buffalo, 2014

25 tissue boxes

182.5 x 68 x 8 cm (71 13/16 x 26 3/4 x 3 1/8 in.)

From the Maharem series

AYD0485

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Reclining Flag, 2012

Steel

77 x 51 x 130 cm (30 3/8 x 20 1/8 x 51 1/8 in.)

From Flag series

AYD0457

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Qist, 2011

Strecthed Ihram fabric on wooden frame.

81 x 160 cm (31 7/8 x 63 in.)

AYD0465

Ayman Yossri Daydban

My Mother's First Embroidered Gown, 2014

Red Textile on Peper

77 x 56 cm (30 5/16 x 22 in.)

AYD0010

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Red Flag, 2014

Industrial car paint on hessian onion bag

128 x 145 cm (50 3/8 x 57 1/16 in.)

AYD0506

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Maharem II, 2015

45 Tissue Boxes

138 x 128 cm (54 5/16 x 50 3/8 in.)

AYD0508

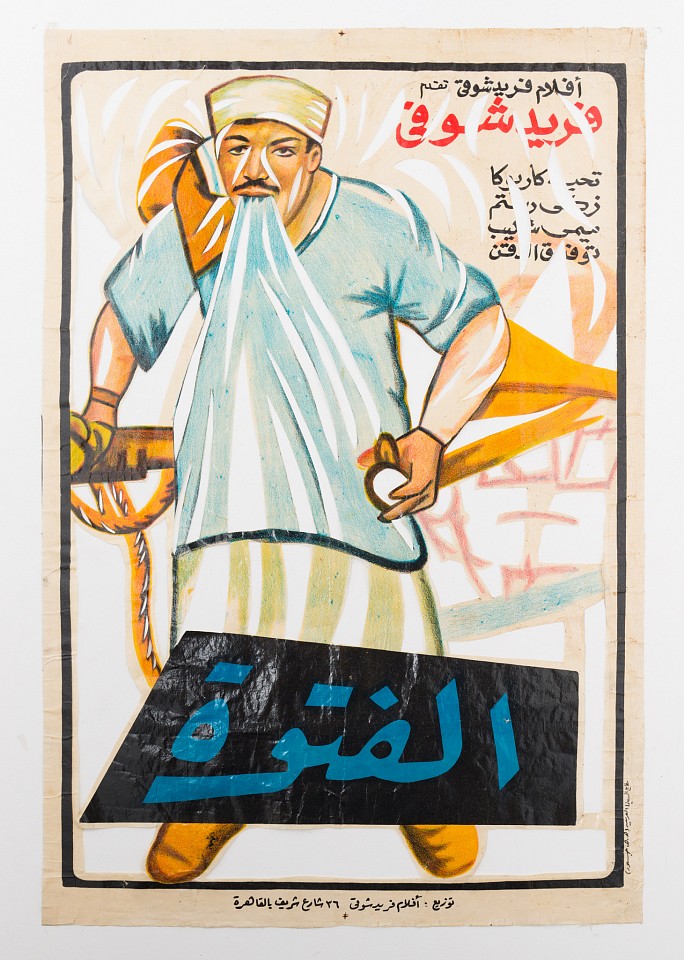

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Al Fotowwa, 2018

Oil on Paper (Vintage Poster)

AYD0725

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Take Me Somewhere Nice series, 2018

Video installation

AYD0682

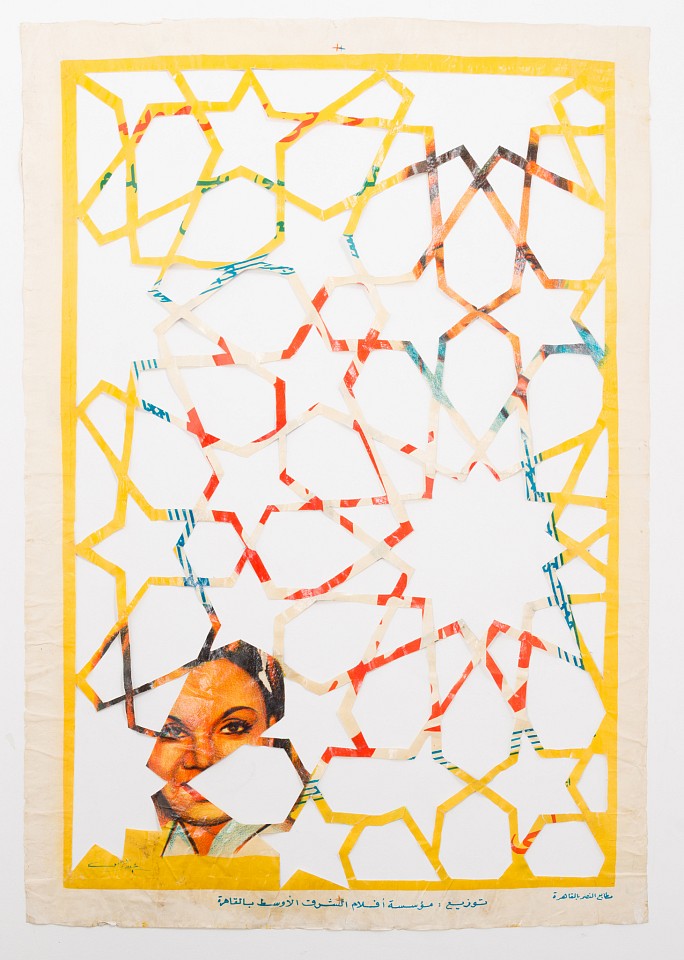

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Untitled, 2018

Oil on Paper (Vintage Poster)

AYD0724

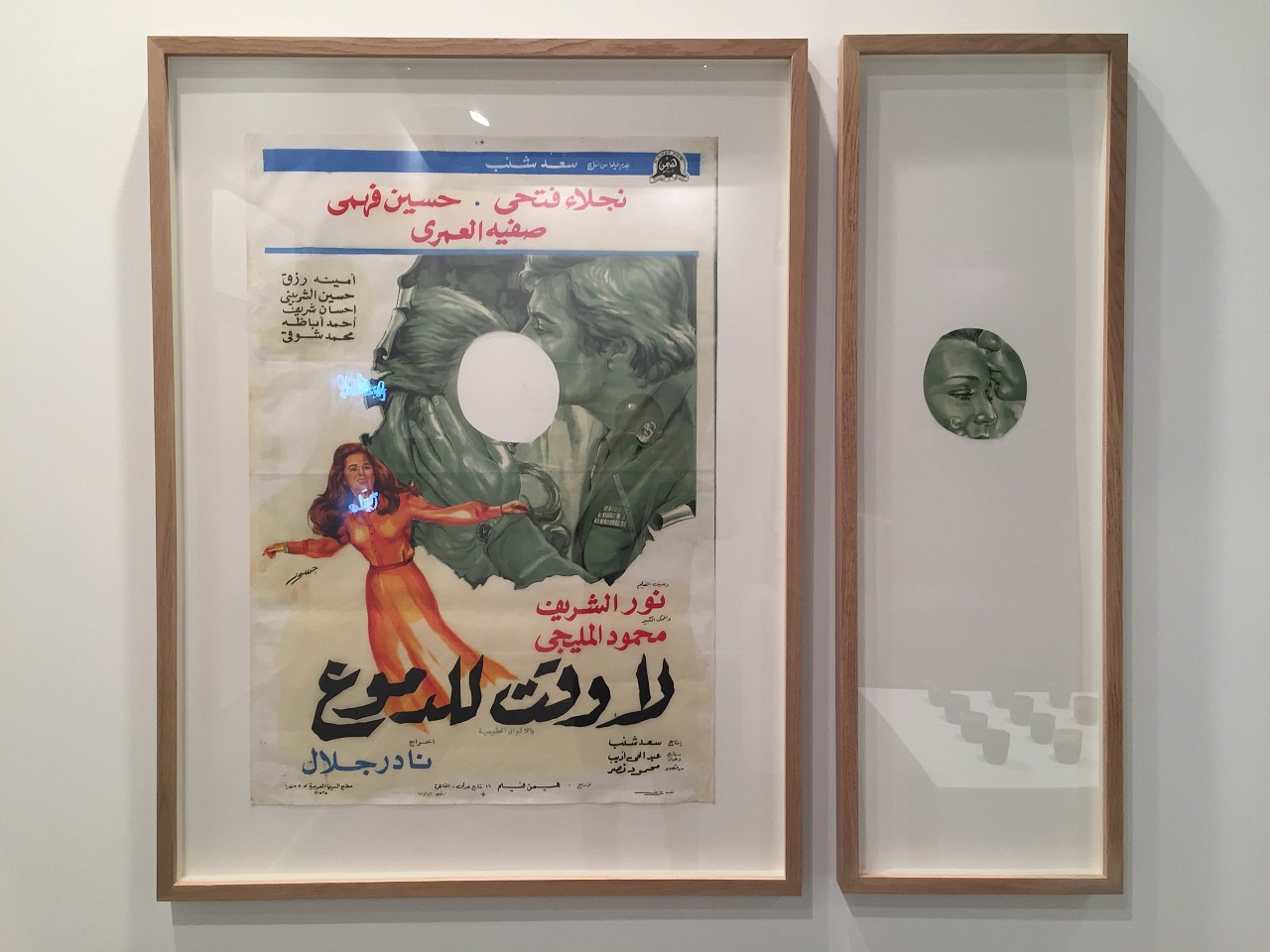

Ayman Yossri Daydban

03 from the Posters series (La Wakta Liddomoo), 2016

Oil on Paper (Vintage Poster)

AYD0615

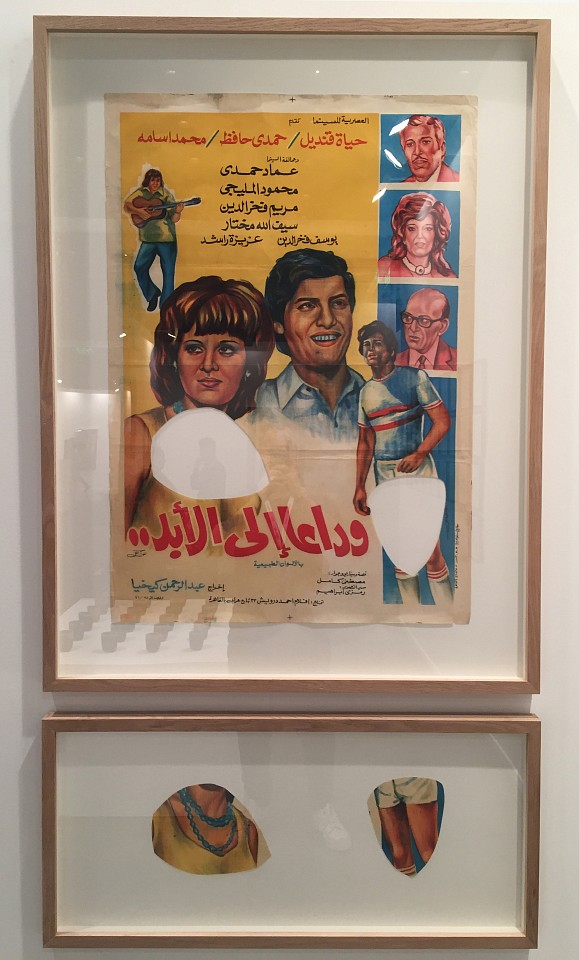

Ayman Yossri Daydban

08 from the Posters series (Wadaan Ela ALabad), 2016

Oil on Paper (Vintage Poster)

AYD0619

Ayman Yossri Daydban

12 from the Posters series (Alawantagiah), 2016

Oil on Paper (Vintage Poster)

AYD0596

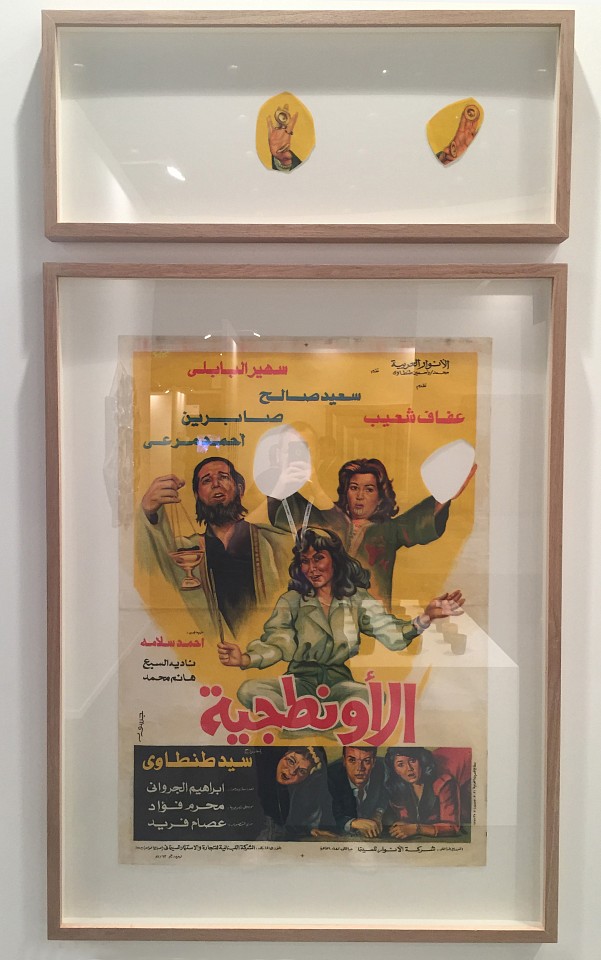

Ayman Yossri Daydban

59 from Maharem series, 2016

Tissue Box

AYD0702

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Daydban 03, 2016

Acrylic on canvas

AYD0624

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Daydban 04, 2016

Acrylic on canvas

AYD0625

Ayman Yossri Daydban

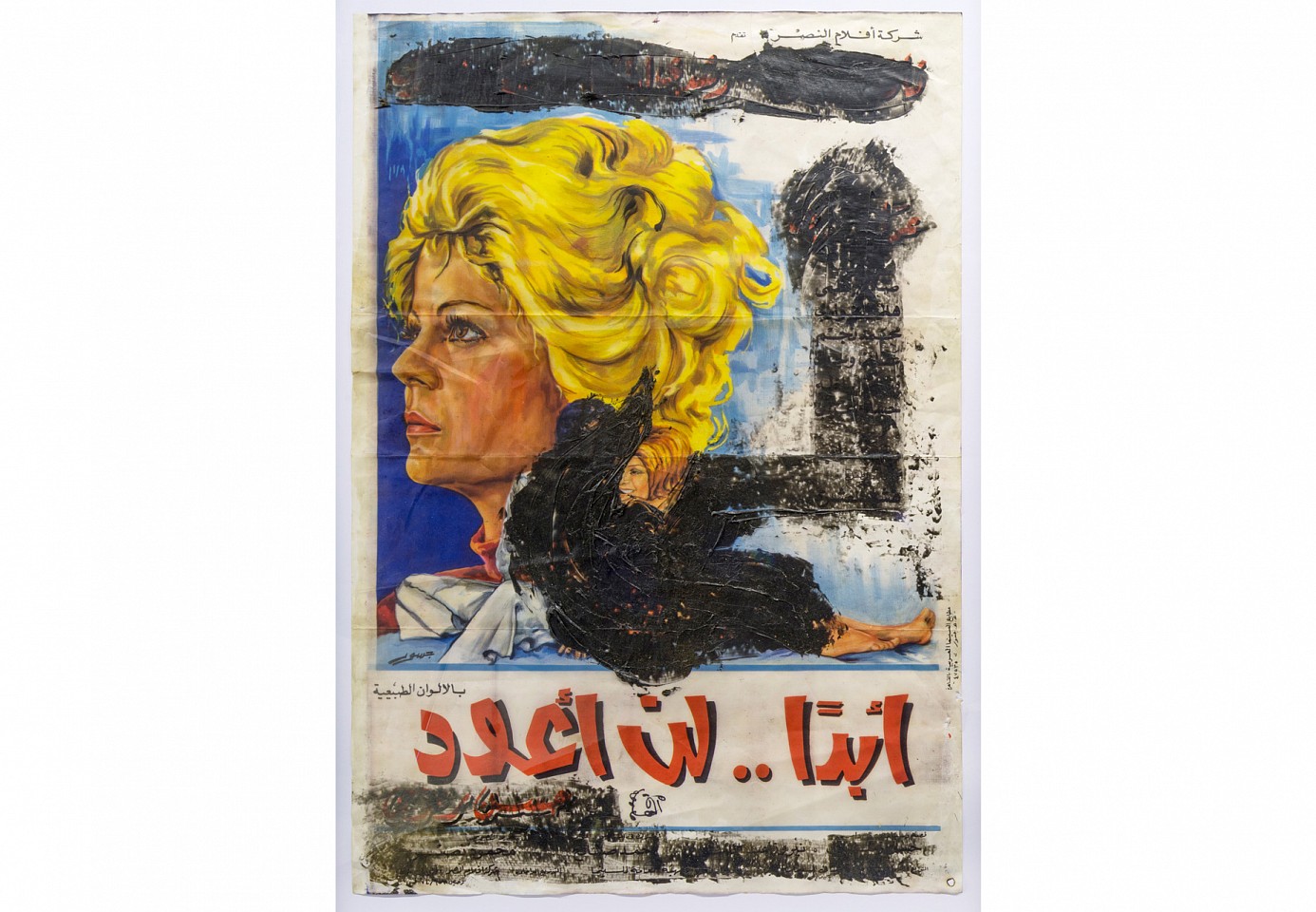

I Will Never Return from My Father Over The Tree series, 2016

Silicone on vintage poster

100 x 70 cm (39 5/16 x 27 1/2 in.)

AYD0572

Ayman Yossri Daydban

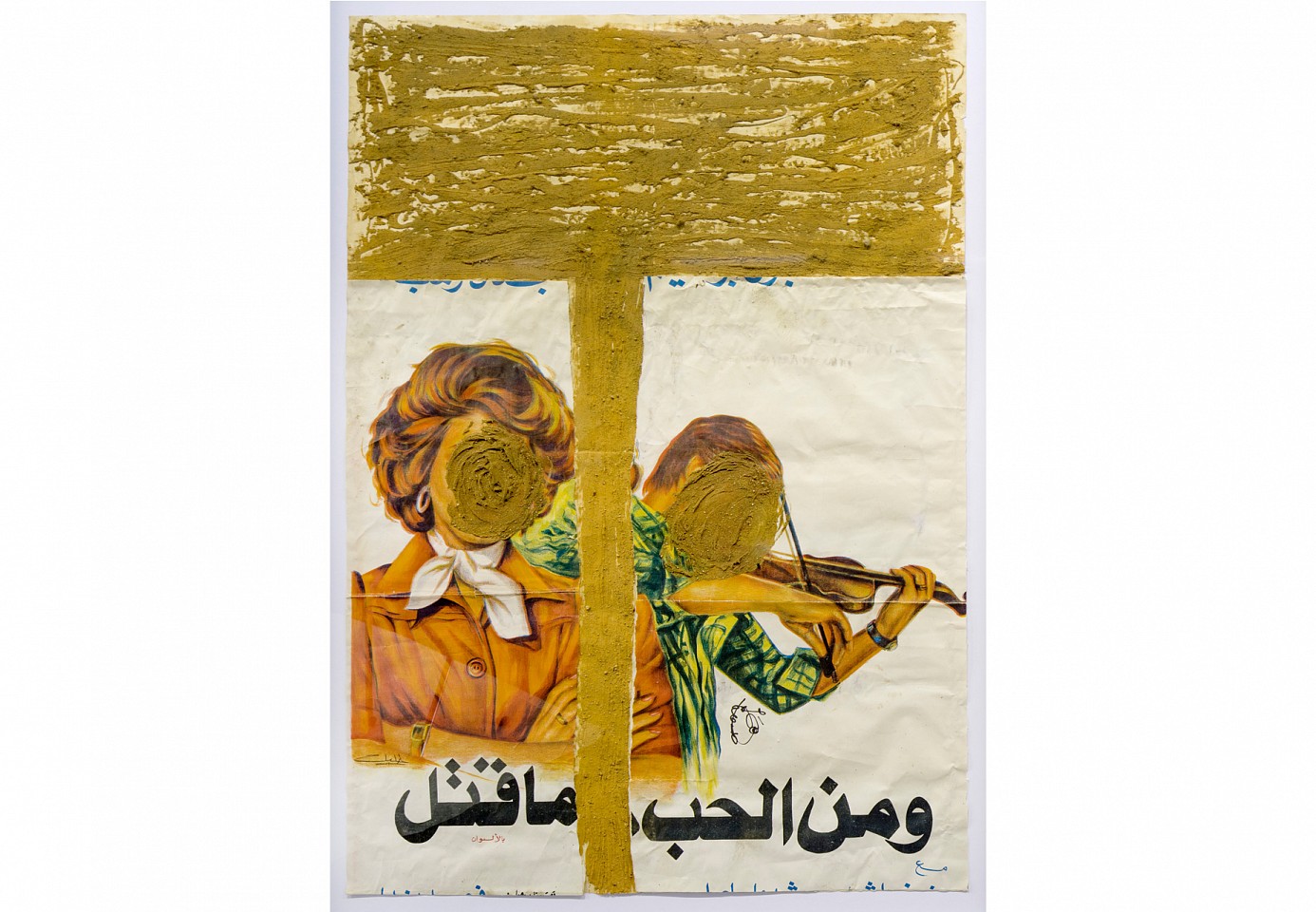

Love Kills from My Father Over The Tree series, 2016

Silicone on vintage poster

100 x 70 cm (39 5/16 x 27 1/2 in.)

AYD0575

Ayman Yossri Daydban

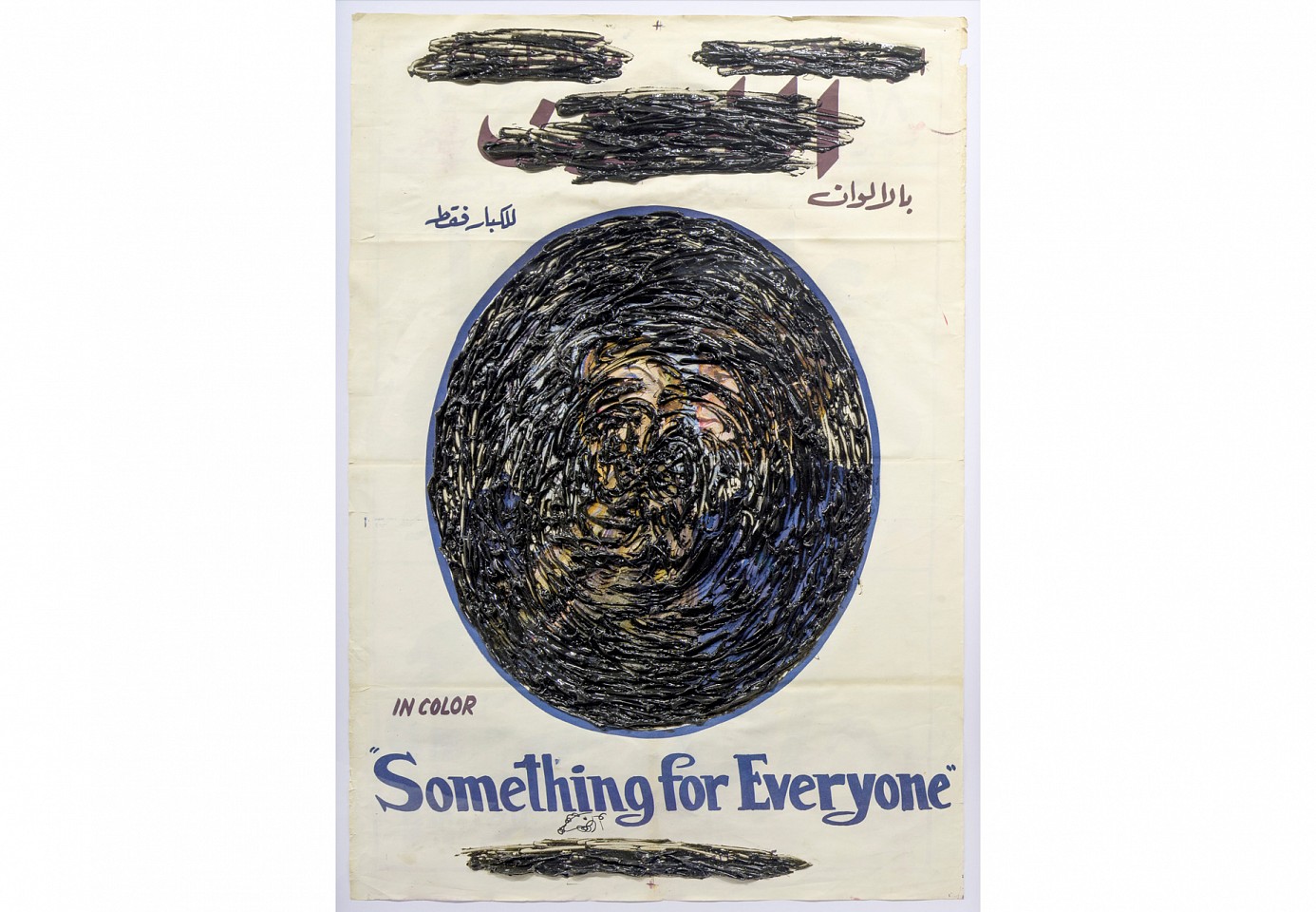

Something For Everyone from My Father Over The Tree series, 2016

Silicone on vintage poster

100 x 70 cm (39 5/16 x 27 1/2 in.)

AYD0573

Ayman Yossri Daydban

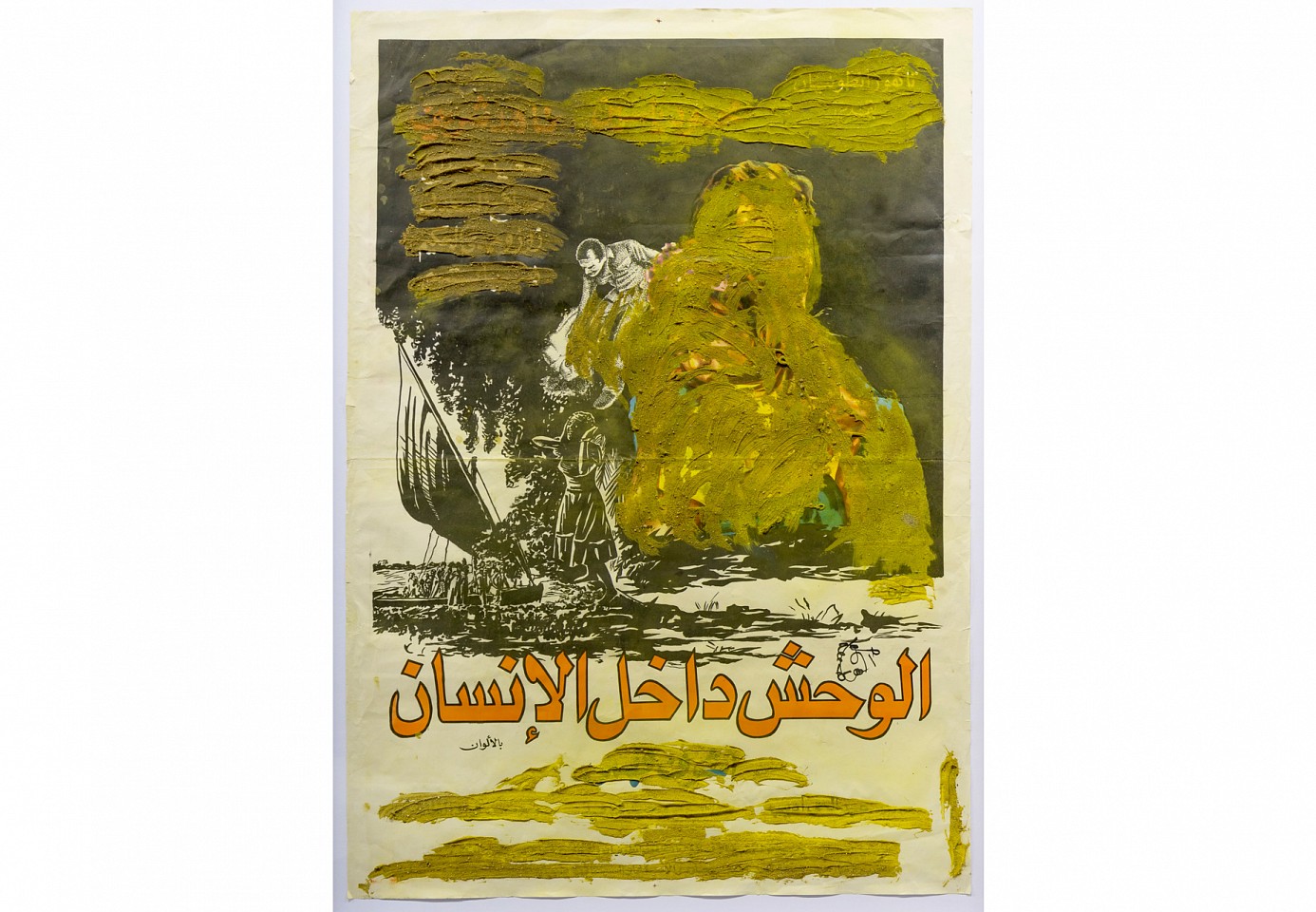

The Inner Beast from My Father Over The Tree series, 2016

Silicone on vintage poster

100 x 70 cm (39 5/16 x 27 1/2 in.)

AYD0574

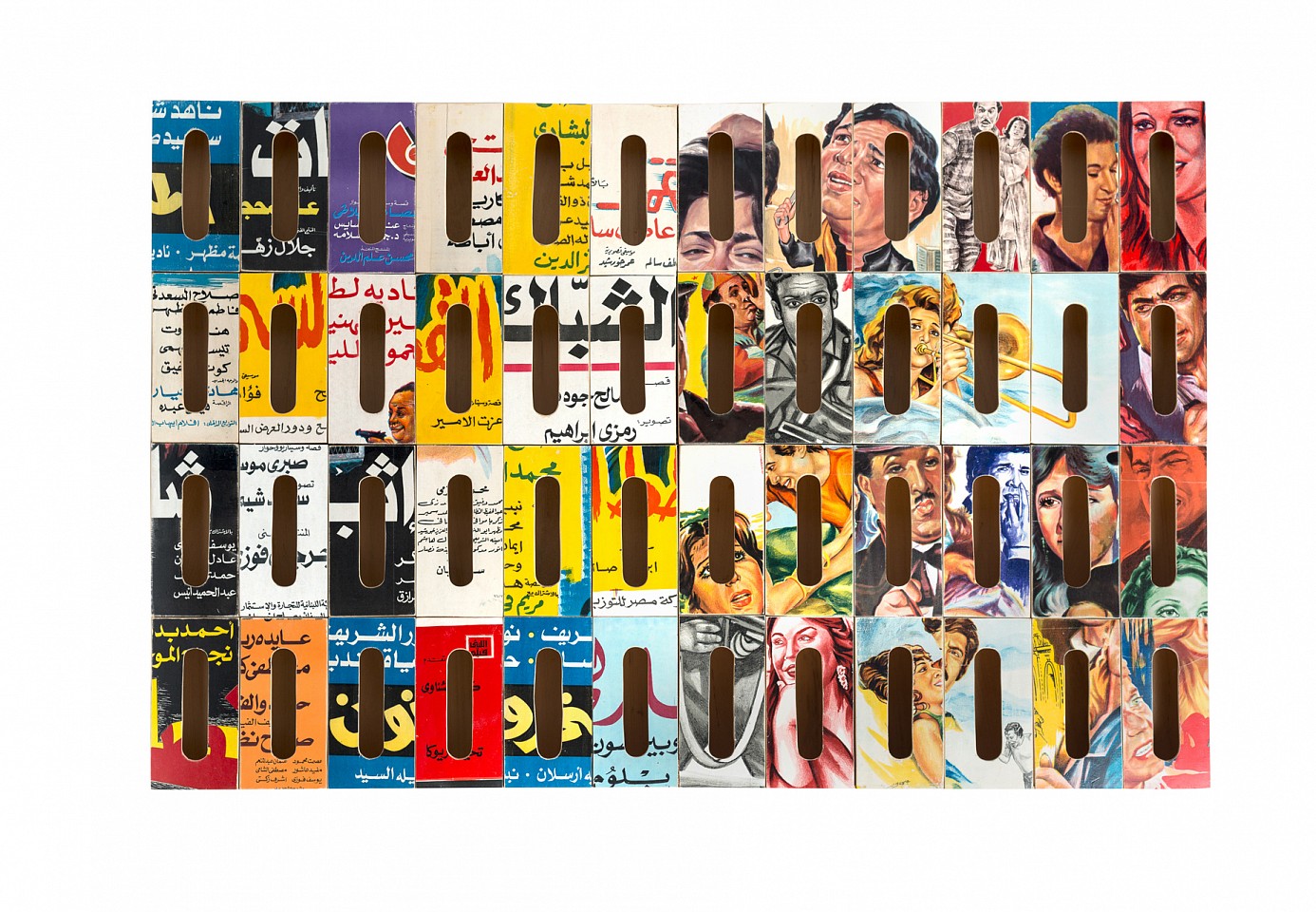

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Untitled 1-8 from the Flower Series, 2016

8 film posters on tissue Boxes (each)

Ayman Yossri Daydban

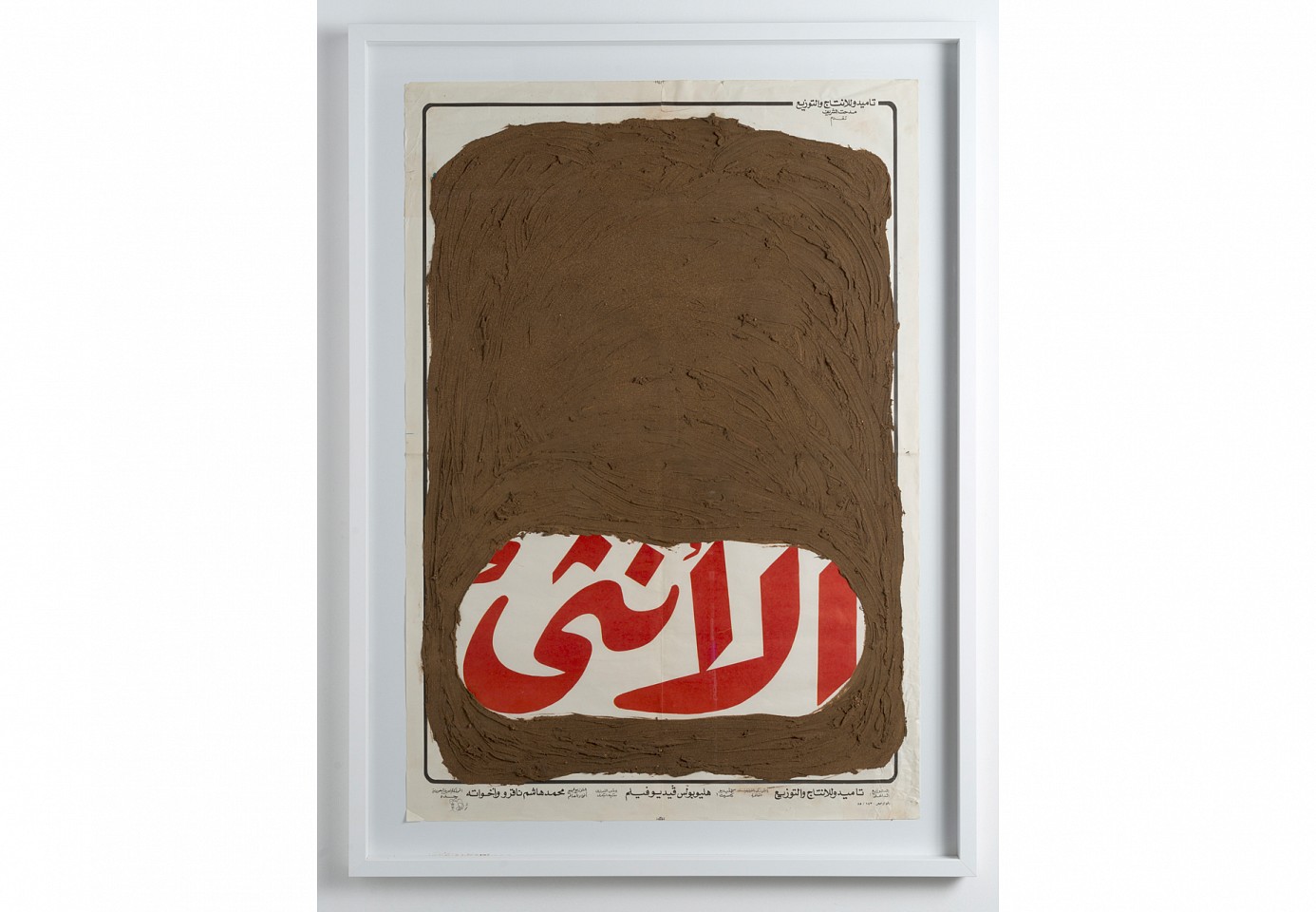

AlOntha (The Female) , 2015

Silicon, soil on vintage posters

113 x 83 cm (44 7/16 x 32 5/8 in.)

AYD0521

Ayman Yossri Daydban

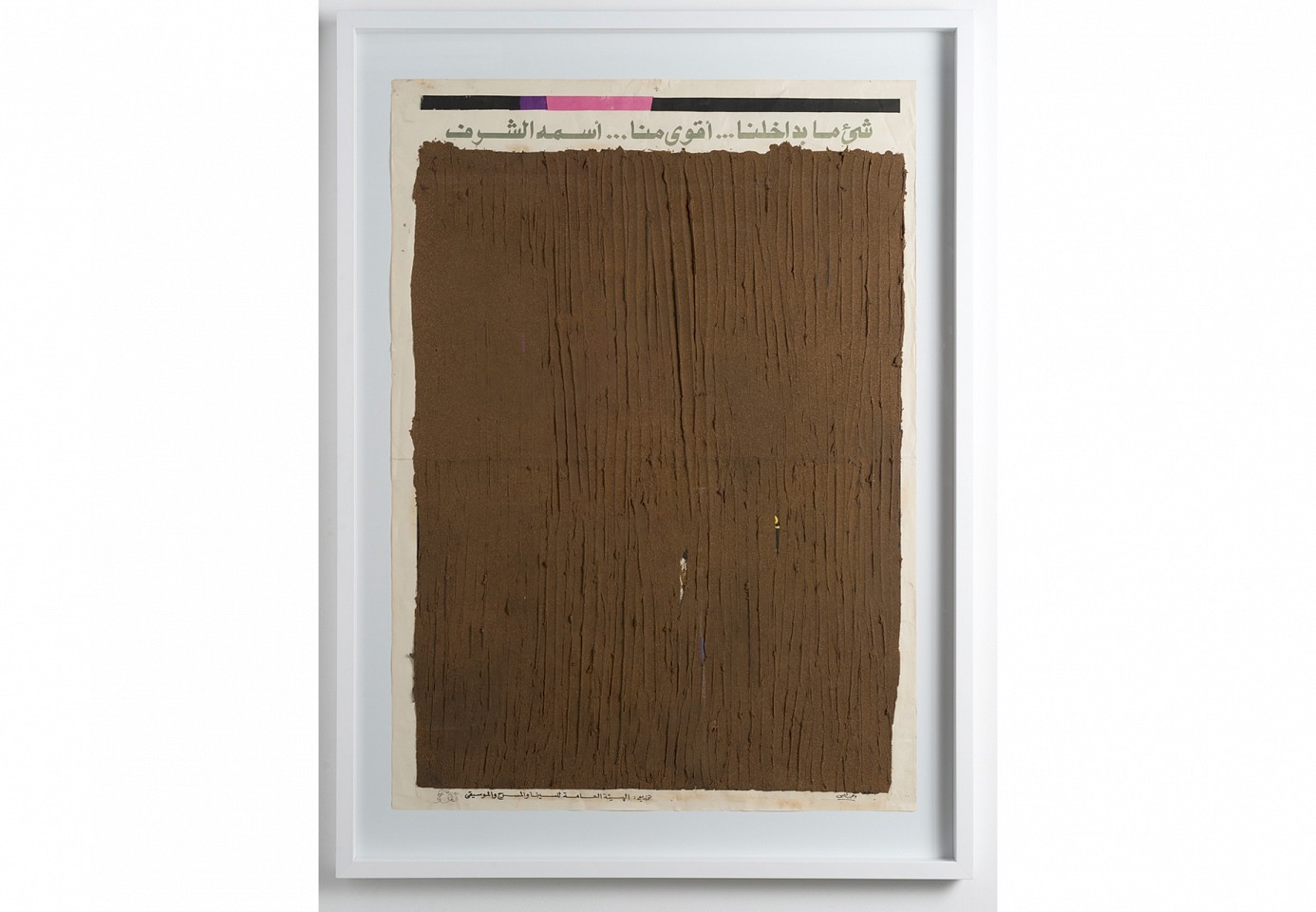

AlSharaf (Honor) from the My Father Over The Tree series, 2015

Silicon, soil on vintage posters

113 x 83 cm (44 7/16 x 32 5/8 in.)

AYD0522

Ayman Yossri Daydban

AlShobak (The Window) from the Maharem series, 2015

Print on tissue boxes

105 x 164 cm (41 5/16 x 64 9/16 in.)

AYD0519

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Single from the My Father Over The Tree series, 2015

Silicon, soil on vintage posters

113 x 83 cm

AYD0523

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Ya Laytany La Amluk fee Hathihi Al Dunya shyaan wa leya om (I wish I had nothing in this world,but had a mother), 2015

Silicon, soil on vintage posters

113 x 83 cm

AYD0524

Ayman Yossri Daydban

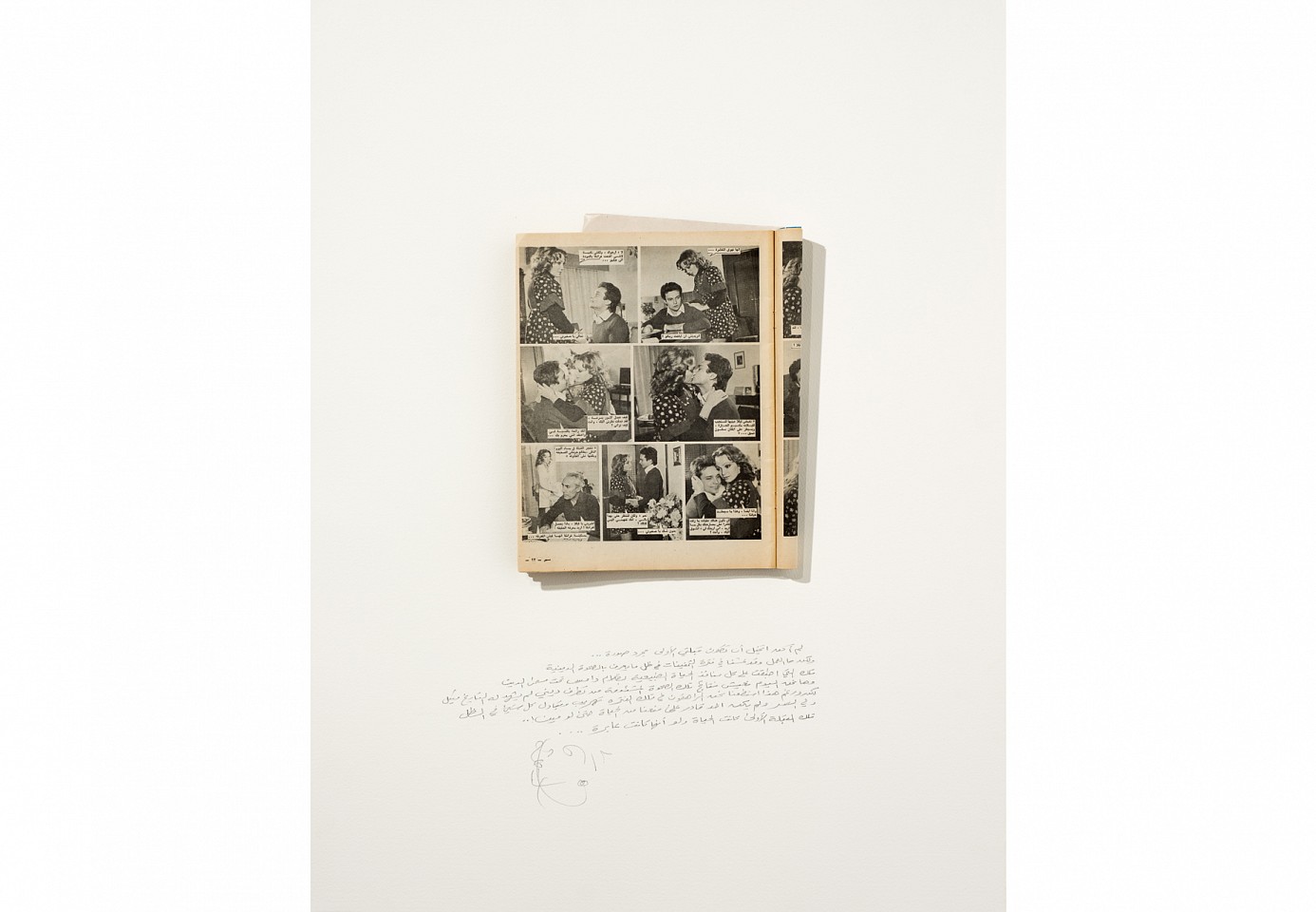

Al Qablah Al Oola - The First Kiss, 2014

Arabic comic on acid free paper

AYD0525

Ayman Yossri Daydban

The First & Last Prayer, 2014

Prayer rug, soil on acid free paper

AYD0526

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Balfour Declaration, 2011

100% Cotton Acid Free Paper

77 x 56 cm (30 3/8 x 22 in.)

AYD0428

Ayman Yossri Daydban

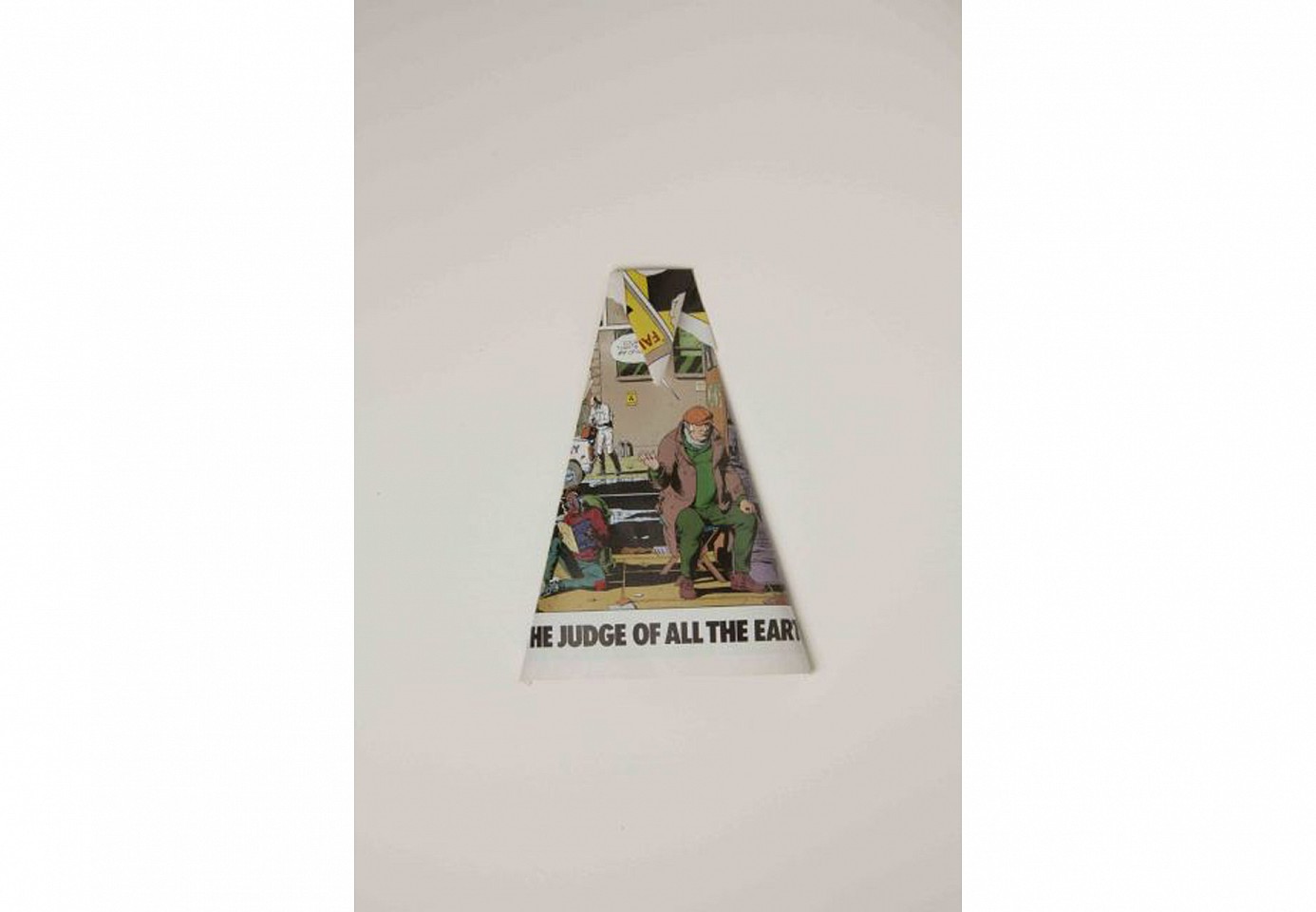

Comics, 2011

100% Cotton Acid Free Paper

77 x 56 cm (30 3/8 x 22 in.)

AYD0426

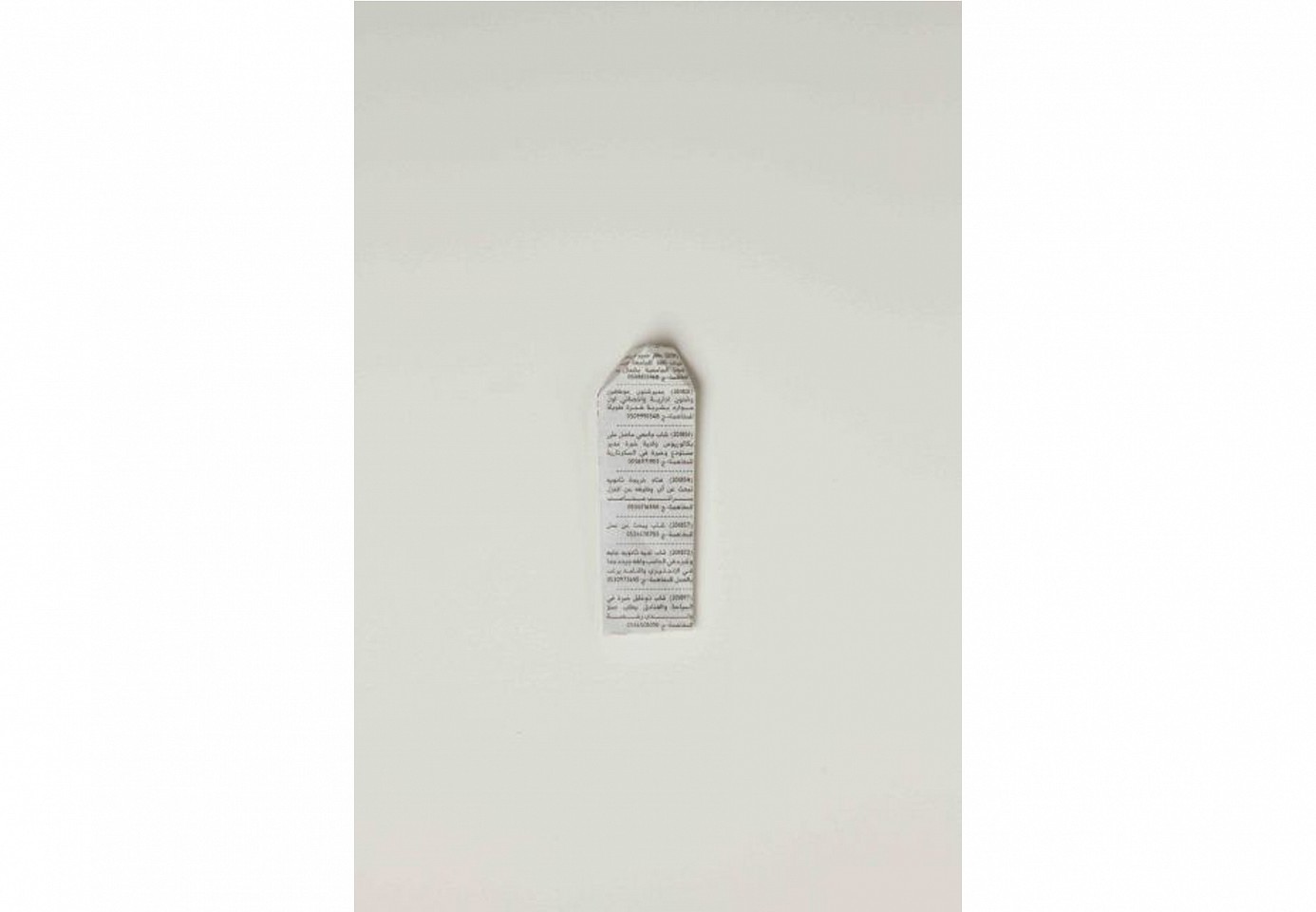

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Job Search, 2011

Mixed Media on Museum Quality Archival Paper

77 x 55 cm (30 3/8 x 21 5/8 in.)

AYD0365

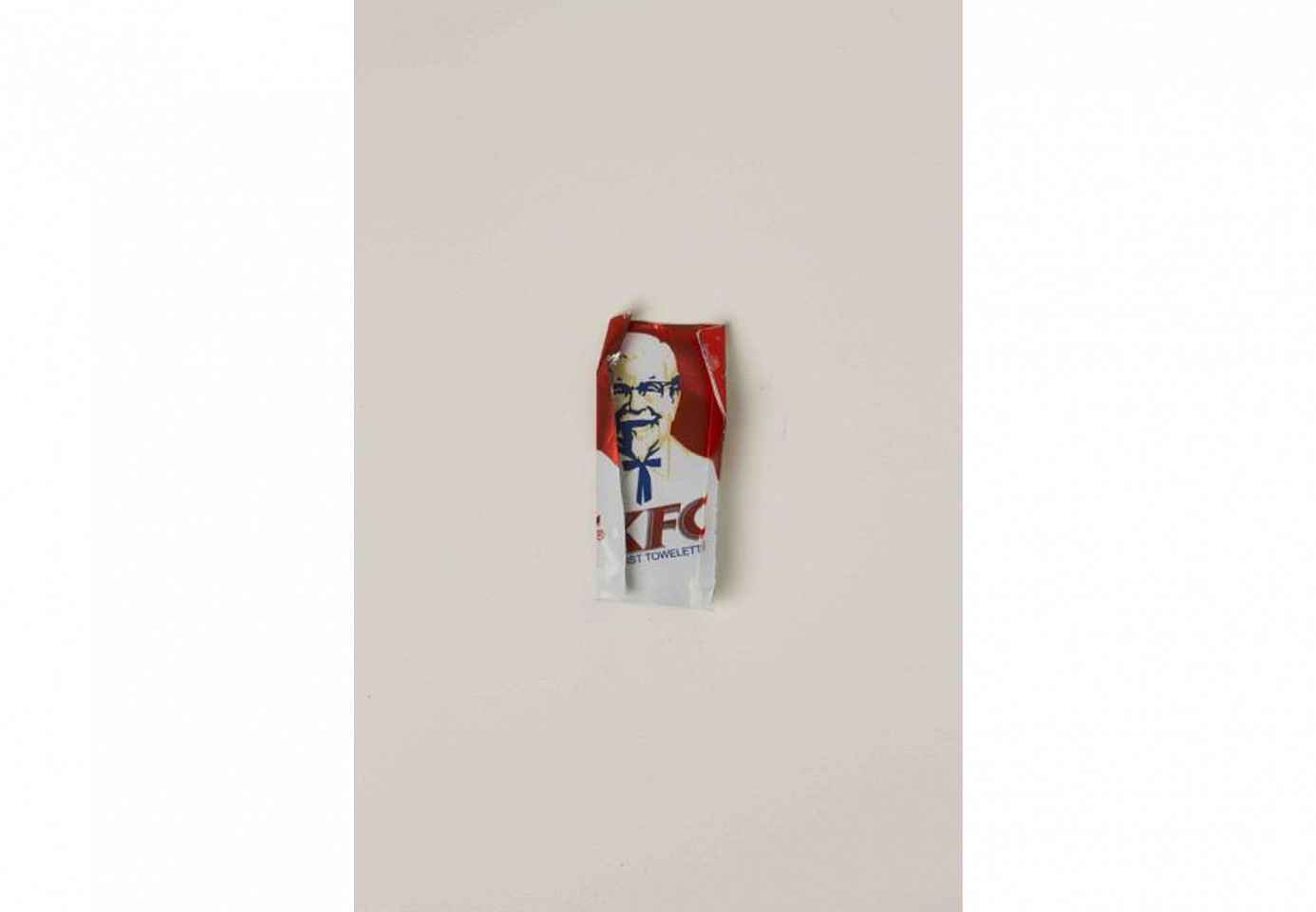

Ayman Yossri Daydban

KFC, 2011

100% Cotton Acid Free Paper

77 x 56 cm (30 3/8 x 22 in.)

AYD0423

Ayman Yossri Daydban

KitKat, 2011

Mixed Media on Museum Quality Archival Paper

77 x 55 cm (30 3/8 x 21 5/8 in.)

AYD0359

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Kunna Jameean Ekhwa, 2010

B&W Lithograph

AYD0301

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Untitled from Daydban series, 2007

Mixed Media on Canvas

61 x 91 cm (24 x 35 13/16 in.)

AYD0532

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Untitled from Daydban series, 2007

Mixed Media

80 x 50 cm (31 7/16 x 19 5/8 in.)

AYD0552

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Divorce II, 2006

Mixed Media on Canvas

122 x 60 cm (48 x 23 9/16 in.)

AYD0571

Ayman Yossri Daydban

The Divorce series, 2006

Mixed Media

122 x 60 cm (48 x 23 9/16 in.)

AYD0545

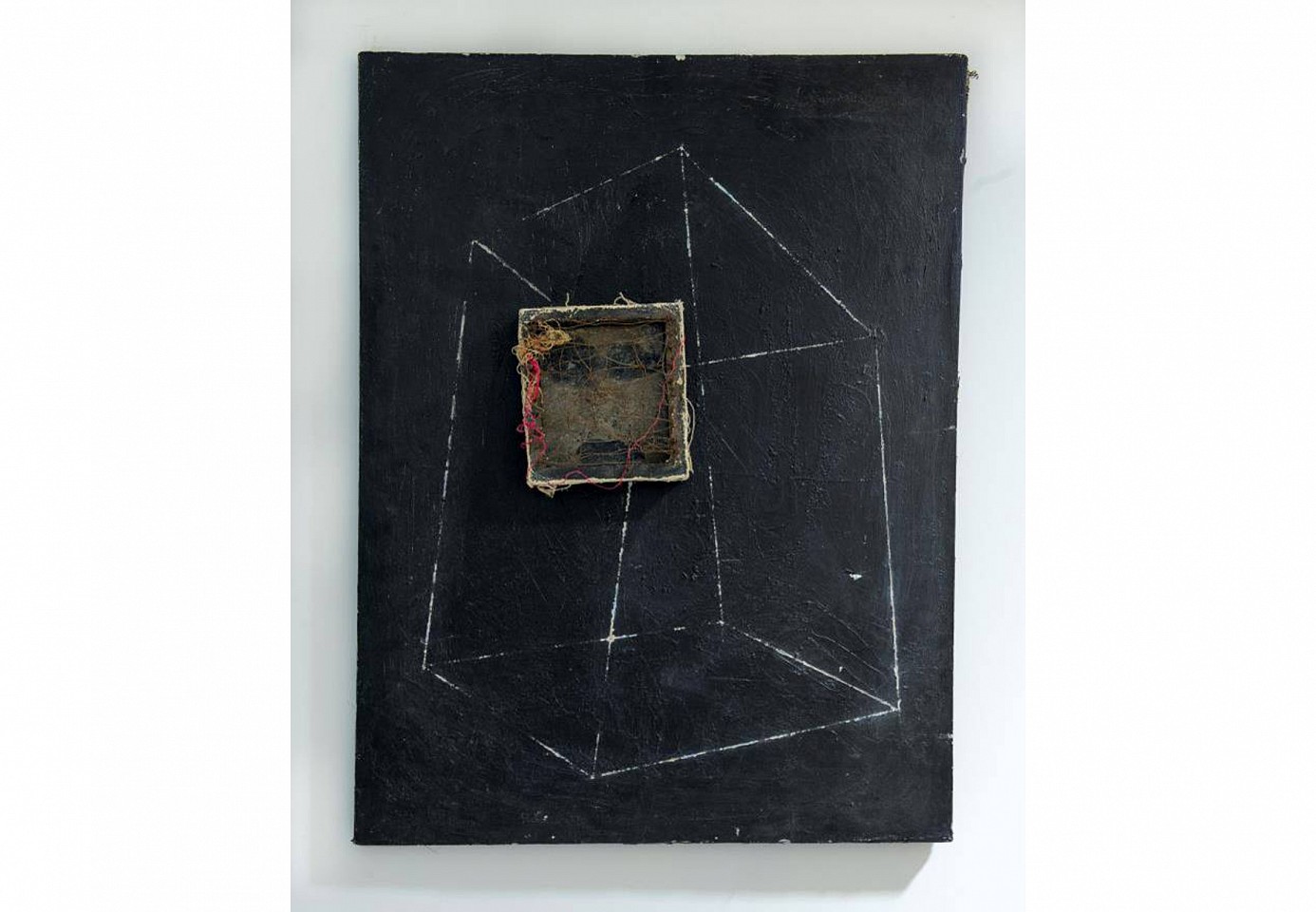

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Untitled from Room series, 2006

Wood

55 x 55 cm (21 5/8 x 21 5/8 in.)

AYD0538

Ayman Yossri Daydban

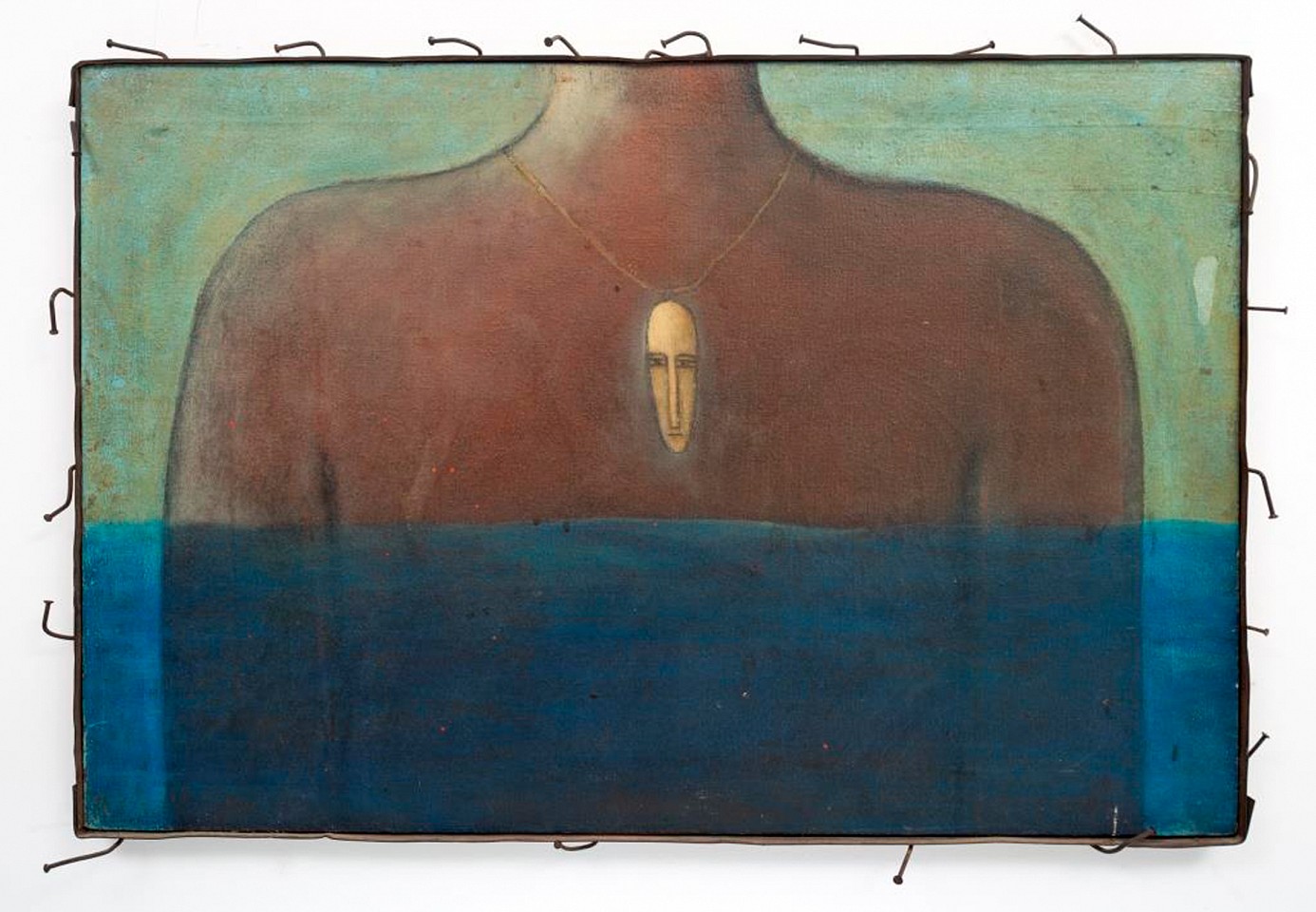

Portrait from Daydban series, 2003

Mixed Media on Canvas

76 x 127 cm (29 7/8 x 50 in.)

AYD0533

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Untitled from Room series, 1999/2016

Mixed Media

76 x 56 cm (29 7/8 x 22 in.)

AYD0536

Ayman Yossri Daydban

Untitled from Room series, 1999

Leather, Ink and Silicone

54 x 70 cm (21 1/4 x 27 1/2 in.)

AYD0535

![Ayman Yossri Daydban, Abeed Al Manazil [The House Negro]

2011, Fujicolor Crystal Archive Print](/images/26986_h125w125gt.5.jpg)

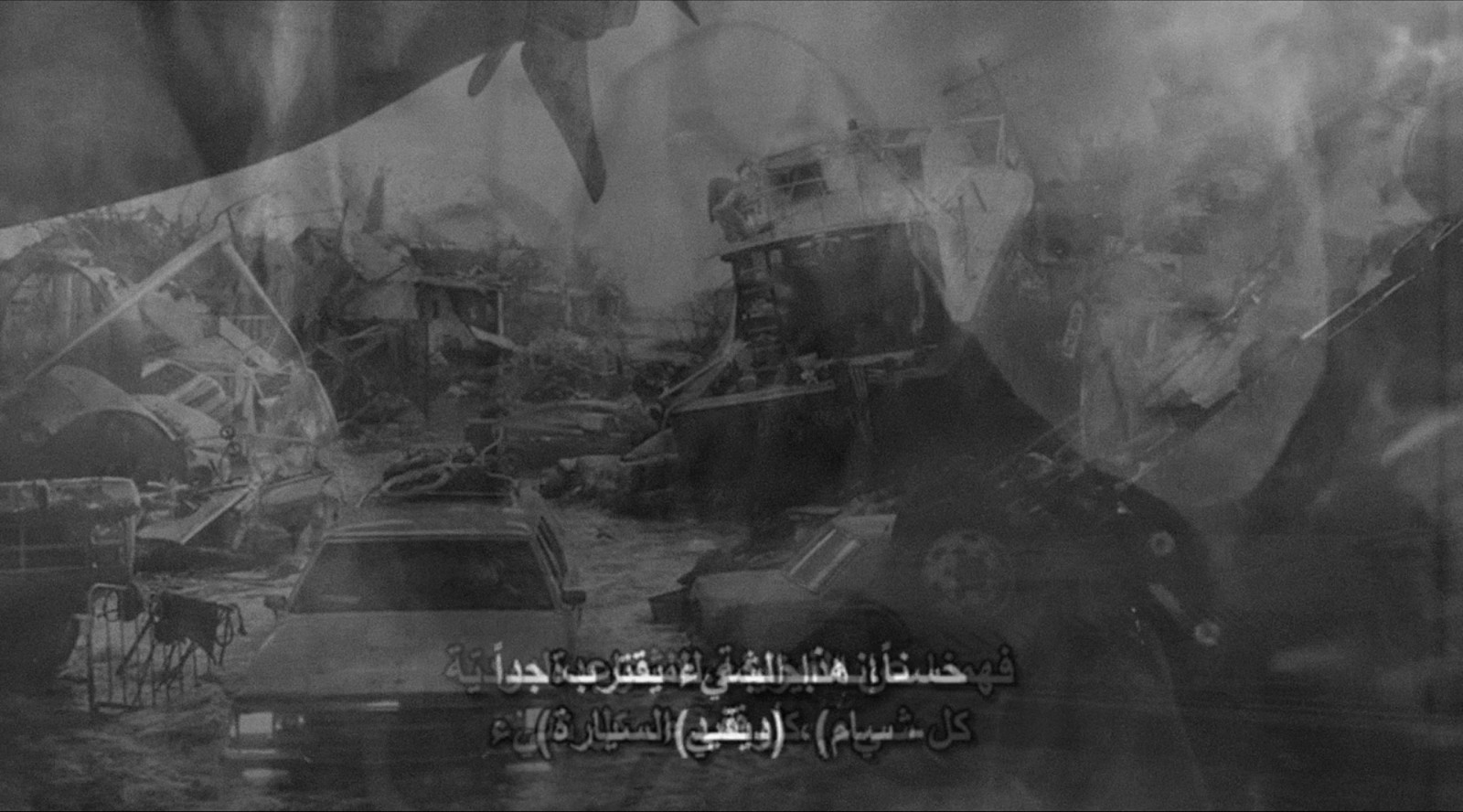

The basic function of Arabic subtitles in a foreign film is translation. The subtitle works within the context of the film as a narration to the story as well as an explanation of the action that accompanies it. As such, the impact of the picture precedes that of the subtitle and creates the framework for it.

When removed from the context of the film, and re-exported with the image of the film still, the function of the subtitle is transformed from confirming meaning to actually producing it. It is re-born as a unique source of content, with no past or alternative function.

The basic function for the Arabic language associated with a foreign language film shown on the screen... is translation. It works in the context of the film as a narration of the story and an explanation of the action that accompanies it ... and thus the meaning of the picture precedes that of the language and specifies it.

The language, when deducted from its cruel context and re-exported with the image of the new still captured photo, changes its function from confirming the meaning to producing it, by transforming itself to a unique source of new mental images with no past or function.

The basic function for the Arabic language associated with a foreign language film shown on the screen... is translation. It works in the context of the film as a narration of the story and an explanation of the action that accompanies it ... and thus the meaning of the picture precedes that of the language and specifies it.

The language, when deducted from its cruel context and re-exported with the image of the new still captured photo, changes its function from confirming the meaning to producing it, by transforming itself to a unique source of new mental images with no past or function.

Ihramaat is a concept born out of a defining tradition and custom adopted during the holy Hajj pilgrimage. In this series, Daydban uses authentic Ihramat, the customary white cloth worn by pilgrims to Makkah, stretched onto wooden frames and presents them in multiple variations. Traditionally, every man performing his pilgrimage is required to wear white cloth. It erases any distinguishing features between himself and his neighbor and presents them as one, stripped down to their purest form, all equal and united under the same faithful brotherhood.

At a distance, the ihram seems identical as they are of the same scale and essentially plain white cloth, but as you approach, distinct patterns begin to appear. Parallels can be drawn between the piece and social ideals, whereby each panel represents a building block in society. Various groups share differences and similarities in their patterning, yet work together under a grater umbrella to flow in peace and harmony.

Borders, flags and other symbols of belonging and identity continuously infuse Ayman Yossri’s oeuvre. For the last 10 years, the artist has been constructing and deconstructing the Palestinian flag, reflecting on a shifting understanding of identity and exile, in a process of constant redefinitions.

Ayman belongs nowhere. His Palestinian identity is fragmented and has lost its form and meaning. His flags are, at times, devoid of colours, reflective metal sheets shaped by the sheer force of his body, showing, in the various phases of unfolding, the effort of the human being to break free from the narrow stereotypes which are imposed on him. At other instances, these flags are pieces of paper and recycled objects, hessian bags painted red, all reflecting on a flag ‘empty’ of ideals, representing the politics of national identity in a globalized world.

The series Maharem originated from the tissue box which middle to lower income families traditionally exhibit in their sitting room for their guests’ convenience. These boxes are usually lavishly decorated with velvet and kitsch gold rims and are often considered decorative masterpieces, a source of pride to the lady of the house. The artist physically manipulates the tissue box, ripping it bare of the comfort of the velvet coating. He then prints movie imagery onto the rough wood, overlaying the scenes and portraits with the direct language of popular sayings, proverbs and riddles.

In Azkiya’a Laken Aghbiya’a, Daydban covers the boxes with fragments of film imagery – actors faces and shreds of titles, subtitles and names. The artist uses the language of fractured montage to reference the saturation of conflicting messaging we receive on a daily basis. Similar to a previous work entitled Love (2013), there is a visual harmony to the work when viewed from a distance, yet on closer inspection we are confronted with discord and uneasy interjections. The artist is commenting on notions of identity, he believes that societies in the Arab world are currently on an unknown trajectory – whilst waters seemingly move in one direction, underlying are currents of uncertainty and unrest. There is a suspense surrounding thoughts and notions of the future, the countries’ identities are being redefined and yet not one person is clear or in control of the proposed or possible conclusion. The only reliable constant in this world being the empathy between us, one for the other.

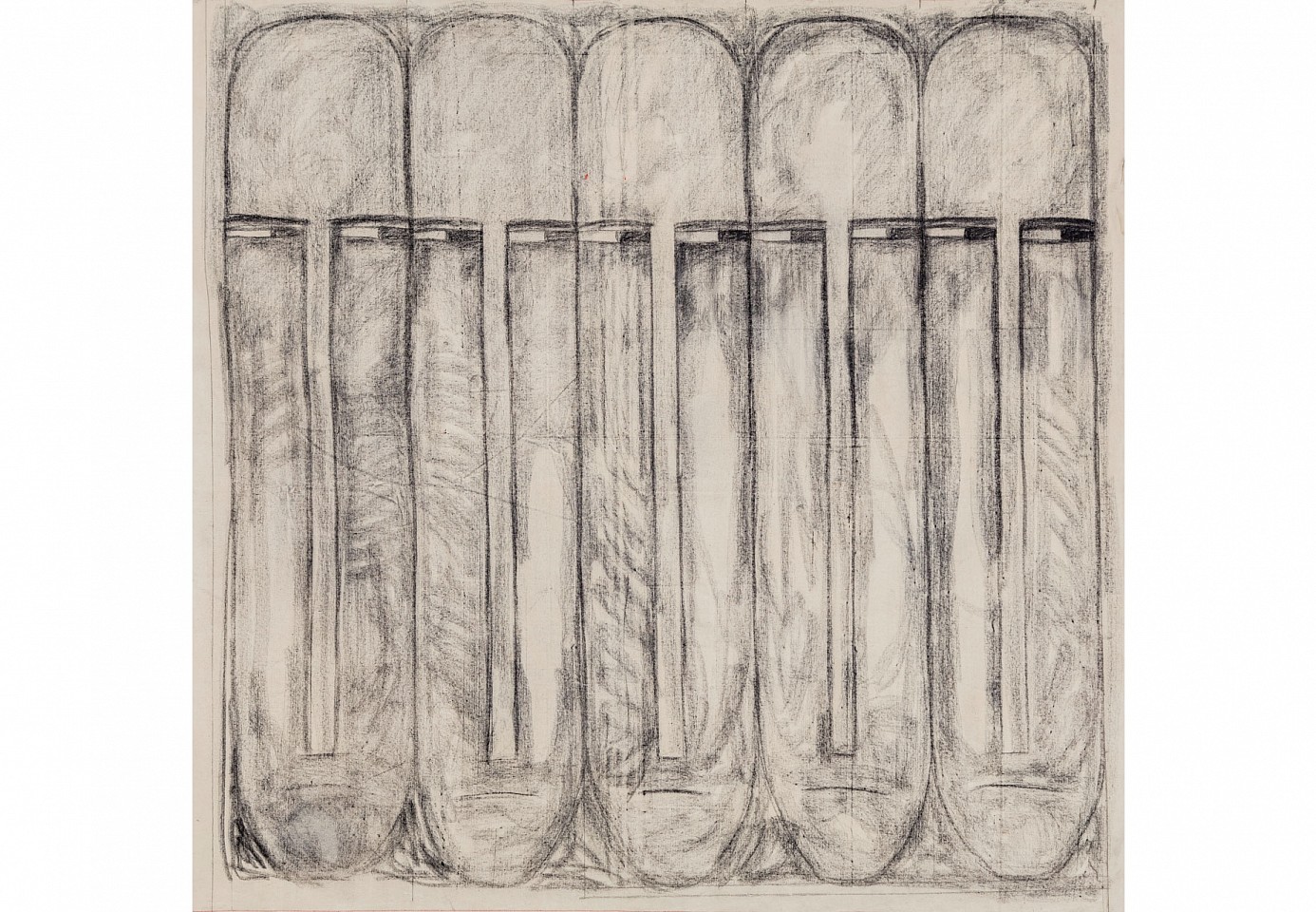

Without light, there is no vision. But to what degree is vision a reflection of reality?

Scientists and philosophers have extensively researched the relationship between light, vision and reality. While we know that different areas of the brain deal with colour, form, motion and texture, our visual system remains too limited to tackle all of the information our eyes take in. And so our minds take shortcuts.

Moreover, since light takes time to reach our eyes, then in reality, the world we perceive is somewhat in the past. And so our minds make predictions in order to perceive the present.

Therefore, how can what one experiences be a direct representation of his/her surroundings? How can reality be real?

Ayman Yossri’s installation of 8 screens consists of compilations of stills from a plethora of movies, documentaries, news report, etc., recorded and played at very high speed. The visual outcome is akin to seeing moving shades of light.

Behind the light of every screen, Ayman Yossri is visually narrating moments, events, stories that have shaped his life, that of others, the region and beyond. The work builds itself into a kind of artist manifesto, broadcasted to the wider public but revealed to none.

The series Maharem originated from the tissue box which middle to lower income families traditionally exhibit in their sitting room for their guests’ convenience. These boxes are usually lavishly decorated with velvet and kitsch gold rims and are often considered decorative masterpieces, a source of pride to the lady of the house. The artist physically manipulates the tissue box, ripping it bare of the comfort of the velvet coating. He then prints movie imagery onto the rough wood, overlaying the scenes and portraits with the direct language of popular sayings, proverbs and riddles.

From the My Father Over The Tree series

Cinemas have been illegal in Saudi since 1980s, when conservative clerics deemed them a corrupt influence.

Ayman Yossri Daydban takes old Egyptian film posters and re-enacts systems of censorship used by the public in Saudi in the 70s, when mud was used to cover areas of posters deemed unacceptable. The work questions the line between censorship and abolition whilst being reminiscent of language once accessible to the general public and media that shaped the artist’s own childhood, contributed to his emotional development and creative practice.

From the My Father Over The Tree series

Cinemas have been illegal in Saudi since 1980s, when conservative clerics deemed them a corrupt influence.

Ayman Yossri Daydban takes old Egyptian film posters and re-enacts systems of censorship used by the public in Saudi in the 70s, when mud was used to cover areas of posters deemed unacceptable. The work questions the line between censorship and abolition whilst being reminiscent of language once accessible to the general public and media that shaped the artist’s own childhood, contributed to his emotional development and creative practice.

From the Room series

I have never imagined that my first kiss would be a mere picture. However, there was nothing we could do, living in the eighties under what was known as the religious awakening; the one which shed darkness on all the outlets of a normal life in the name of religion. Here we are today suffering the results of this ill-fated awakening through an unprecedented religious extremism. Despite this context, we succeeded as teenagers at that time in bringing in and exchanging everything clandestinely and secretly and absolutely no one could prevent us from living! This first kiss was life even if it were transient.

From the Room series

I have never imagined that my first kiss would be a mere picture. However, there was nothing we could do, living in the eighties under what was known as the religious awakening; the one which shed darkness on all the outlets of a normal life in the name of religion. Here we are today suffering the results of this ill-fated awakening through an unprecedented religious extremism. Despite this context, we succeeded as teenagers at that time in bringing in and exchanging everything clandestinely and secretly and absolutely no one could prevent us from living! This first kiss was life even if it were transient.

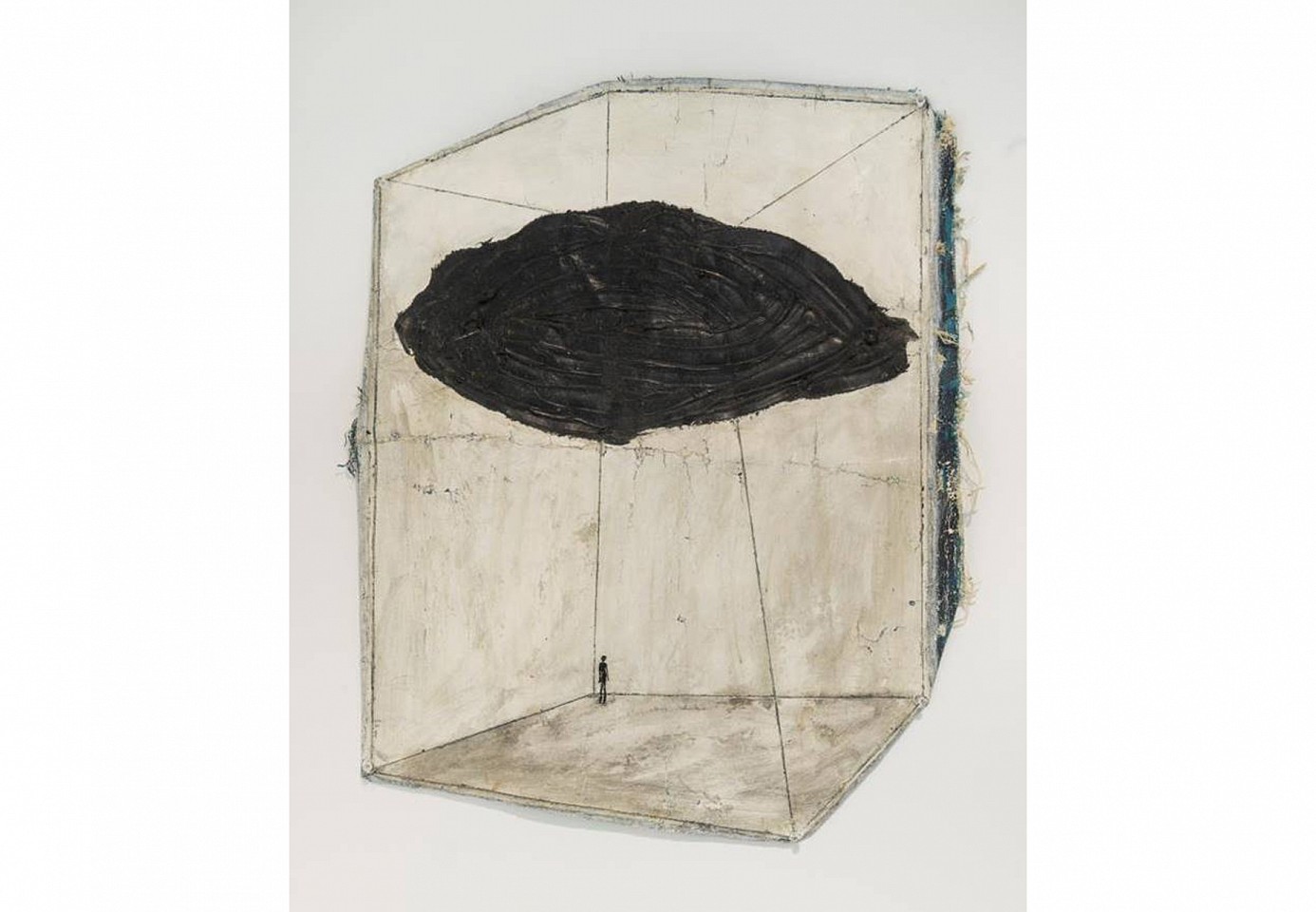

The artist created the work during a period of his life in which he had experienced the trials and tribulations of separation, and there after divorce. Exploring his emotional state with a series of work that depict the anxiety, frustration and confusion he had experienced during this time.

![<p><span class="viewer-caption-artist">Ayman Yossri Daydban</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-title"><i>Abeed Al Manazil [The House Negro]</i></span>, <span class="viewer-caption-year">2011</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-media">Fujicolor Crystal Archive Print</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-dimensions">26 x 51 cm each; 8 pieces</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-description">From the Subtitle series

Edition of 3 + 1 AP</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-inventory">AYD0315</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-aux"></span></p>](/images/26986_h960w1600gt.5.jpg)