Saudi Arabia's cultural scene is in a moment of decisive shift

December 14, 2021 - THE ART NEWSPAPER by Melissa Gronlund

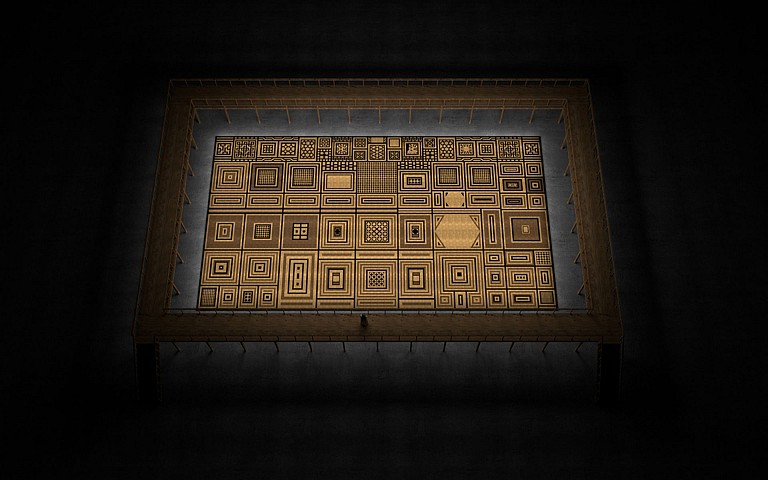

Sarah Abu Abdallah and Ghada Al Hassan, Horizontal Dimensions (2021)Image: courtesy of Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation

“I wanted to think about the emerging Saudi ecology in a global context,” says Philip Tinari, the Beijing-based curator of the inaugural Diriyah Biennale in Riyadh (until 11 March), which contrasted contemporary Saudi Arabia with China in the 1980s, when the country faced a similar relaxation of social and legal restrictions.

“First, to avoid terms like ‘catching up’ or ‘borrowing from’. Comparing this moment with that of China provides a different way into some of these questions. China is another country that’s quite different from the Western reality, and that’s prone to misunderstanding. How do you think about or contextualise the very specific and very precious energy of this moment of optimism and openness?”.

The framework was a punt for Tinari: China’s internal detente quickly seized up after 1989. And the biennial overall was a punt for Saudi’s ministry of culture, the behemoth-like organisation that only opened two years ago and which oversees the Diriyah Biennale Foundation; a specifically international exhibition for a country that has been shunned internationally. (The biennial was endlessly tagged as the “first Saudi biennial”—ignoring, perhaps, Desert X Al Ula, whose roll-out two years ago did not go nearly so well.)

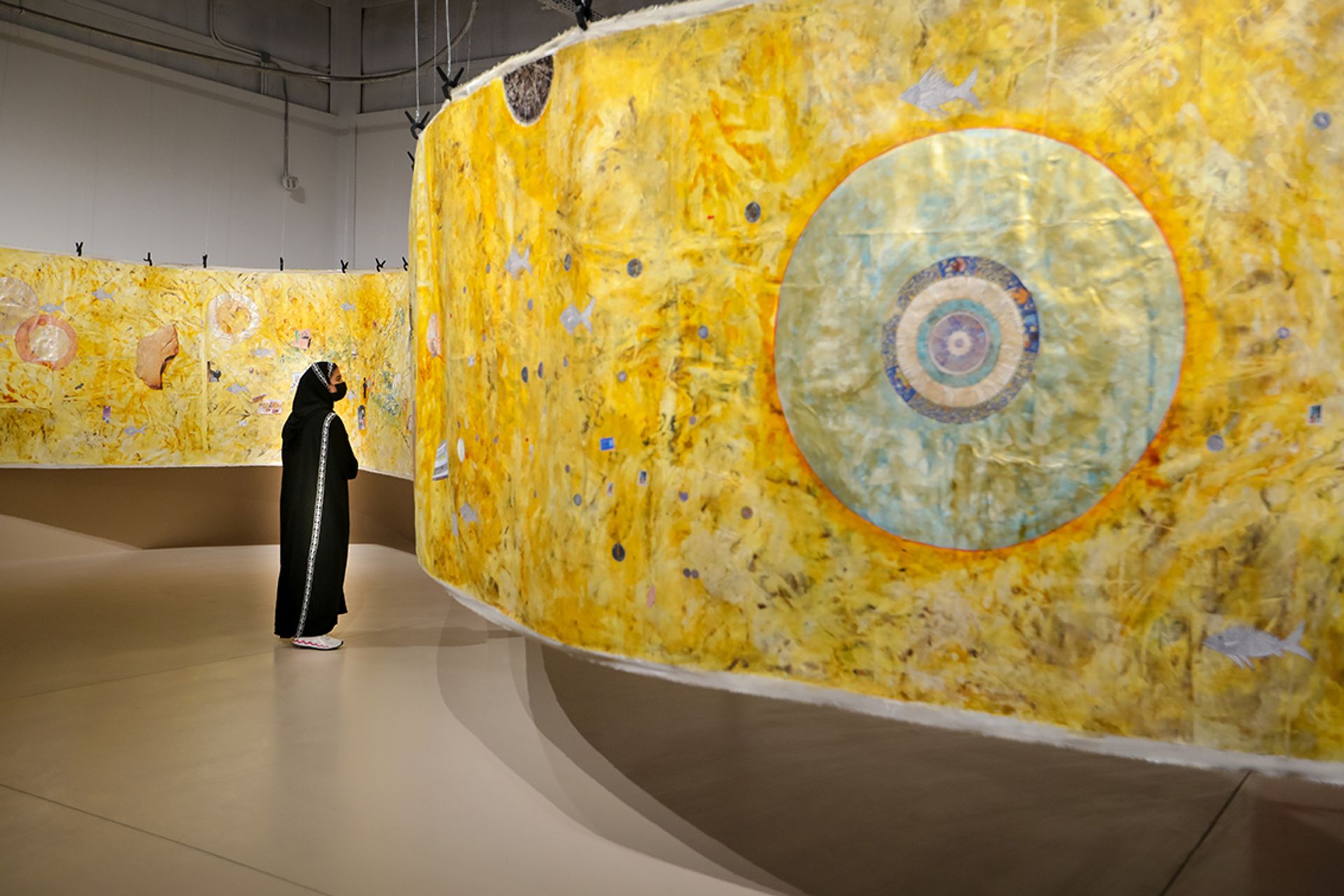

Maha Malluh, Food for Thought, WORLD MAP (2021)Image: courtesy of Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation

But it landed. While the choice of Tinari—the head of the UCCA in Beijing—might reflect the country’s economic and political shift towards China, it also allowed the biennial to join a lineage of biennials in the 1970s and 80s across the Arab region and South and East Asia, and latterly the Sharjah Biennial, in which Western art was the exception rather than the rule. Working with the curators Wejdan Reda, Shixuan Luan and Neil Zhang, Tinari delivered an exhibition that felt rooted in a Saudi context while also opening it up towards parallels in other countries, not just China but also African countries like Morocco, Kenya, and Egypt, for whom art served different means of defining a modern identity.

And while the dusty Riyadh air was thick with pronouncements of “game-changing” and even “world-changing,” the hyperbole was not far off. For the relatively isolated Saudi art scene, 2021/22 will be a moment of decisive shift.

Over the past two weeks, Saudi’s main cities of Jeddah and Riyadh disgorged a ludicrous amount of programming: the Diriyah Biennale, the highly important opening of Hayy Jameel, the Tuwaiq sculpture commissions for public art in Riyadh; Misk Art Week’s exhibitions and discursive programmes; the Jeddah edition of the roving Bienal Del Sur; the Red Sea International Film Festival; various pop-up events; and—last but not least—an art fair, Shara Art + Design. And the second edition of Desert X Al Ula, in February, is right around the corner.

Coming out of isolation

Saudi artists are calling it “the escape from the Dark Ages”, as the explosion of infrastructural growth finally matches the enthusiasm and activity that has been on the ground in Saudi over the past decade.

What is important is not just the amount but the international orientation. Saudi’s cultural policy has had three main priorities, explains Rakan Ibrahim Al-Touq, the general supervisor of strategy and international relations at the ministry of culture. The first is access to culture locally and the second is culture as a mode of economic growth. These have predominated so far, in programmes engineered towards raising Saudi quality of life, such as Riyadh Art, or in giving opportunities to the young population, such as Misk’s and the Red Sea International Film Festival’s grants. But now internationalism is on the make.

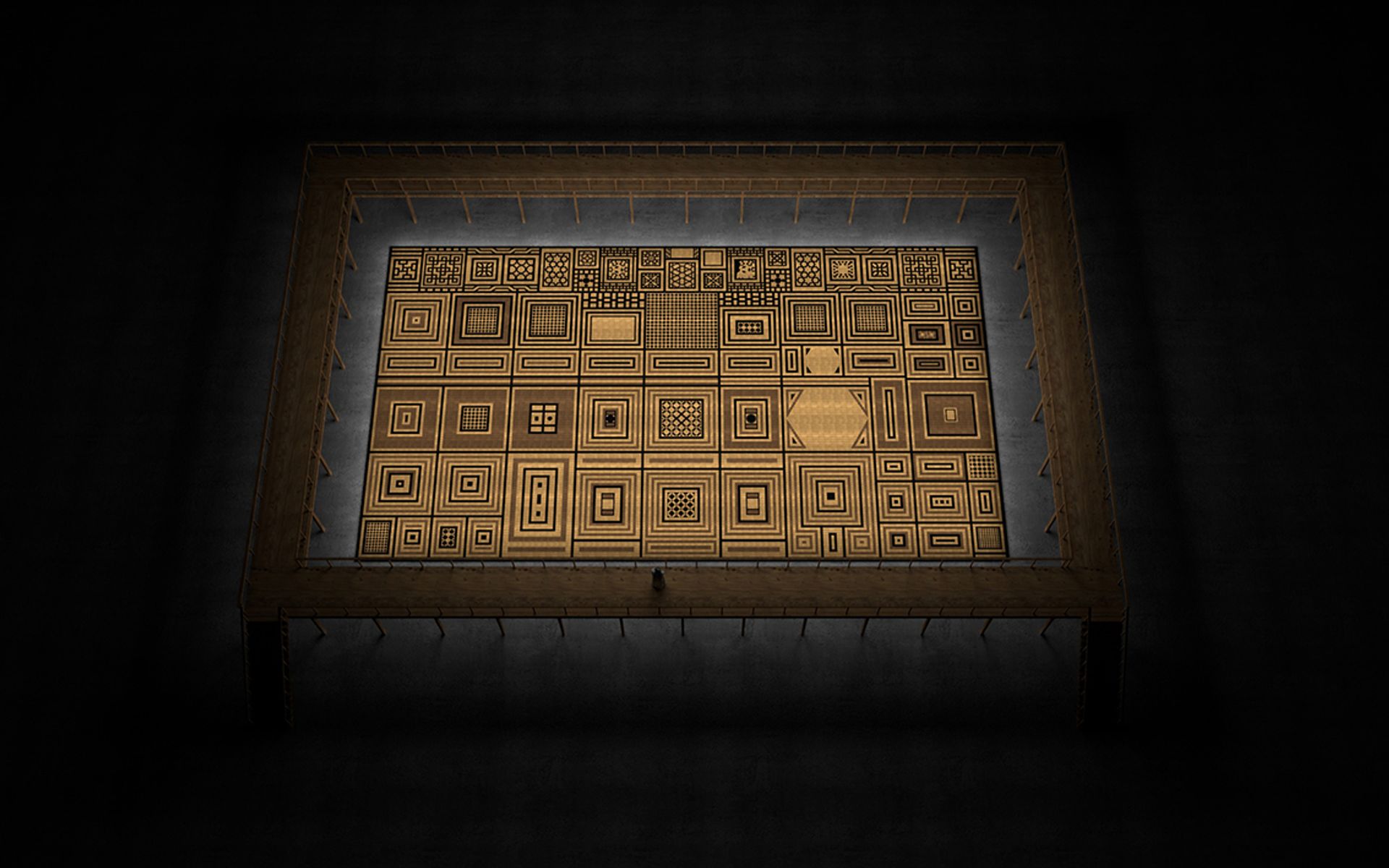

“The best thing about the biennial is for the local artists to get a better understanding and sense of international artists who are working at a high standard,” says the Jeddah artist Dana Awartani, whose re-creation of the destroyed floor of the Great Mosque of Aleppo was a standout of the biennial. “A lot of artists here are used to producing and selling at galleries or art fairs. We’ve not had a not-for-profit space, besides the Saudi Art Council. For me, the biennial is mostly educational—we need the whole infrastructure of education, from schools to universities, to spaces like Hayy that will give you stimulating workshops and talks and programming.”

Dana Awartani, Standing on the Ruins of Aleppo (2021)© Diriyah Biennale Foundation and the artist

Back to News