Dana Awartani

Dana Awartani

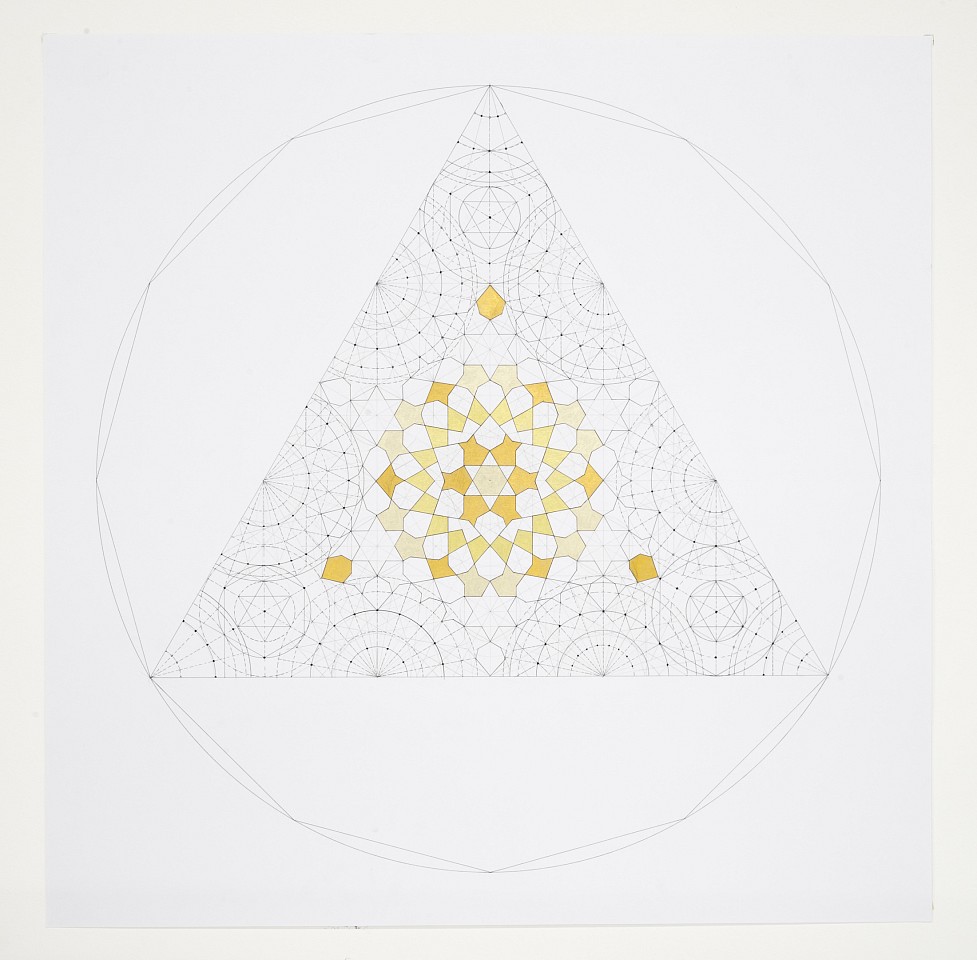

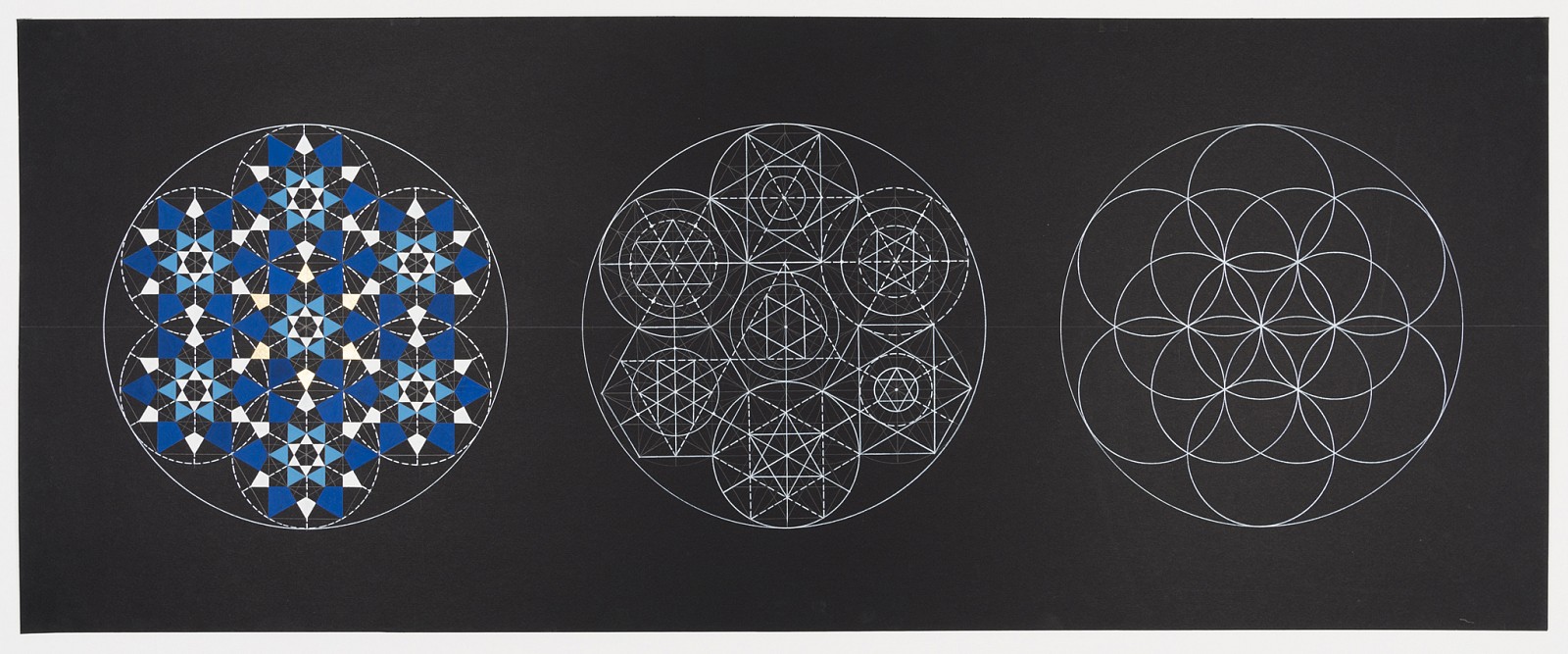

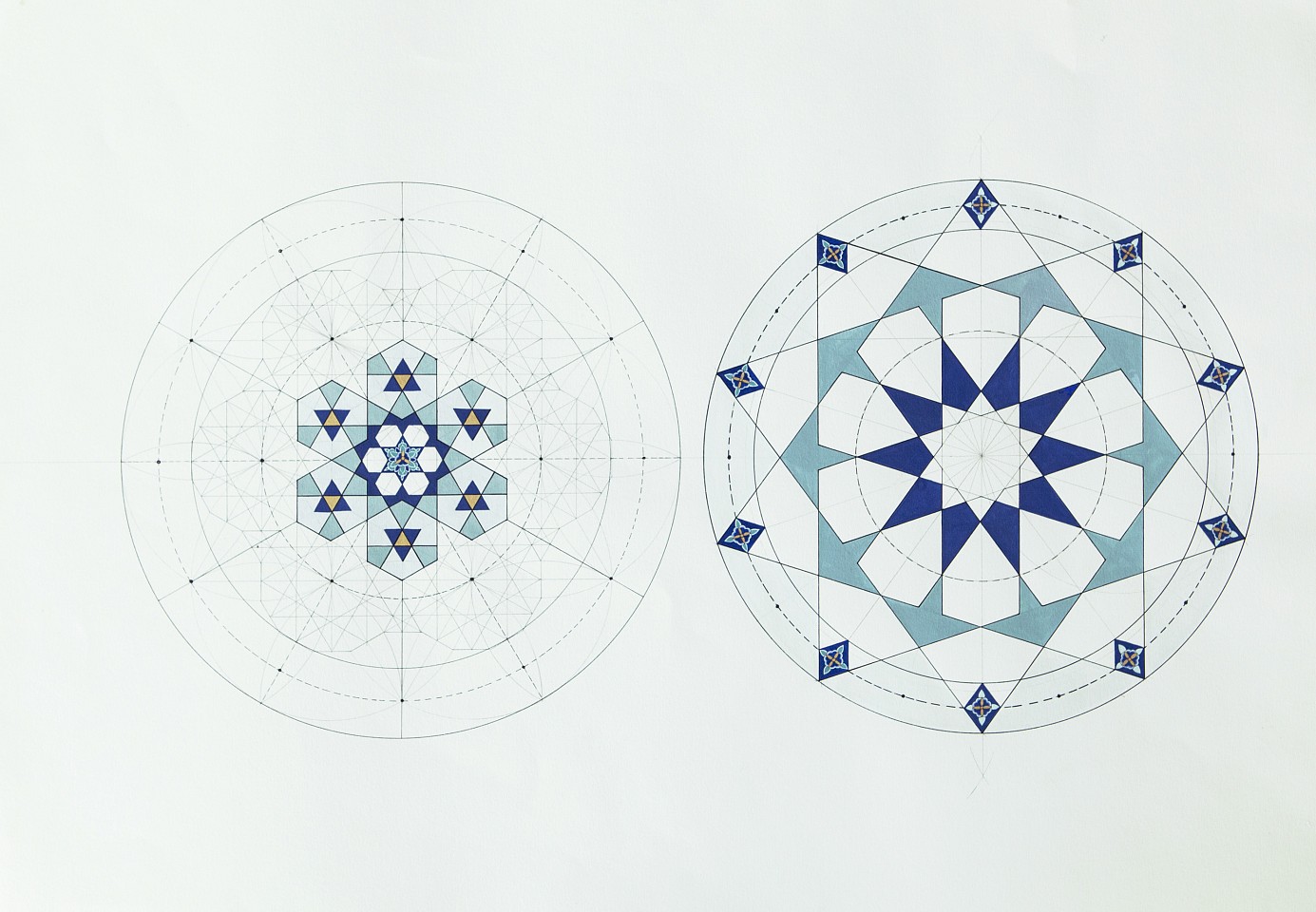

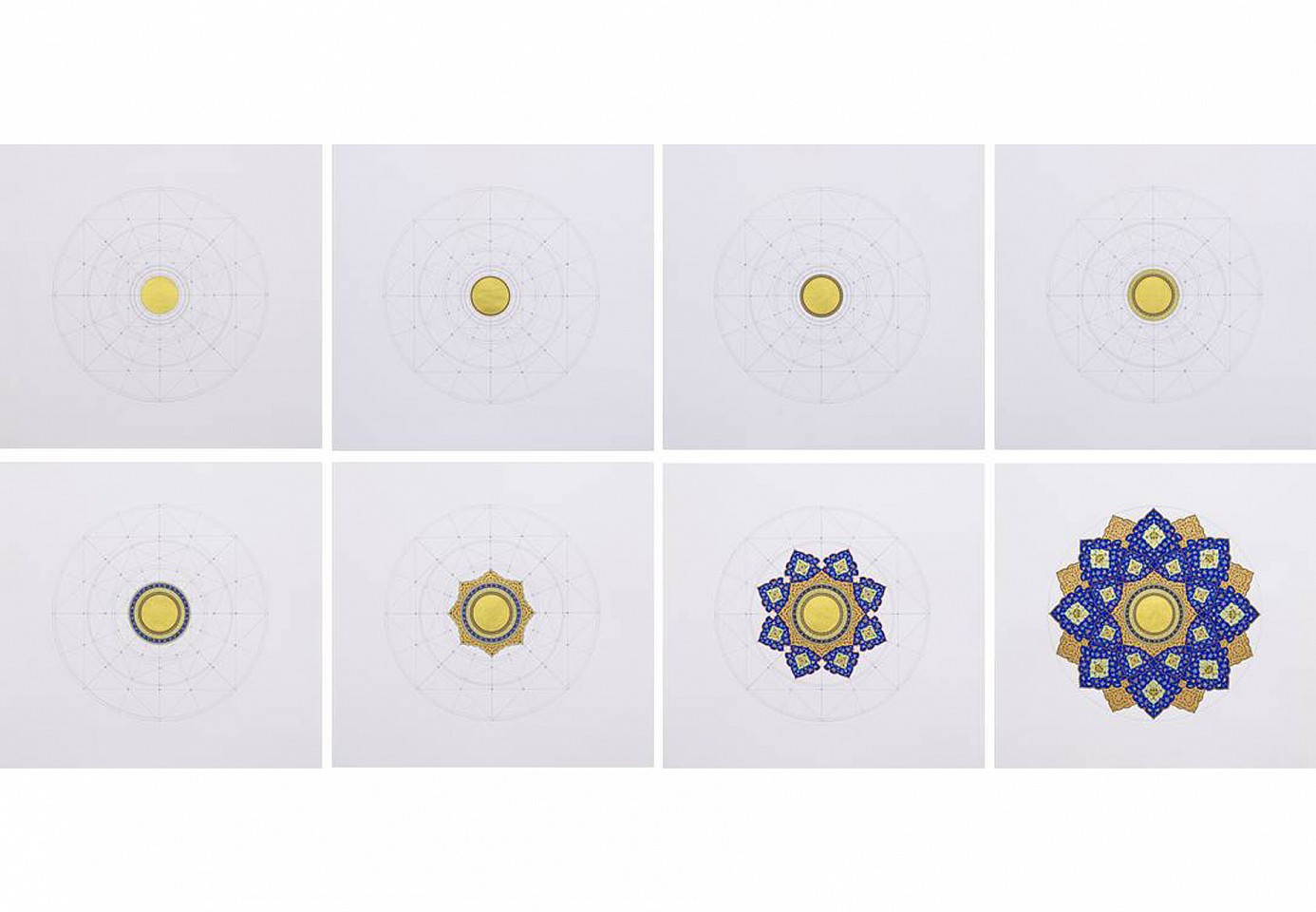

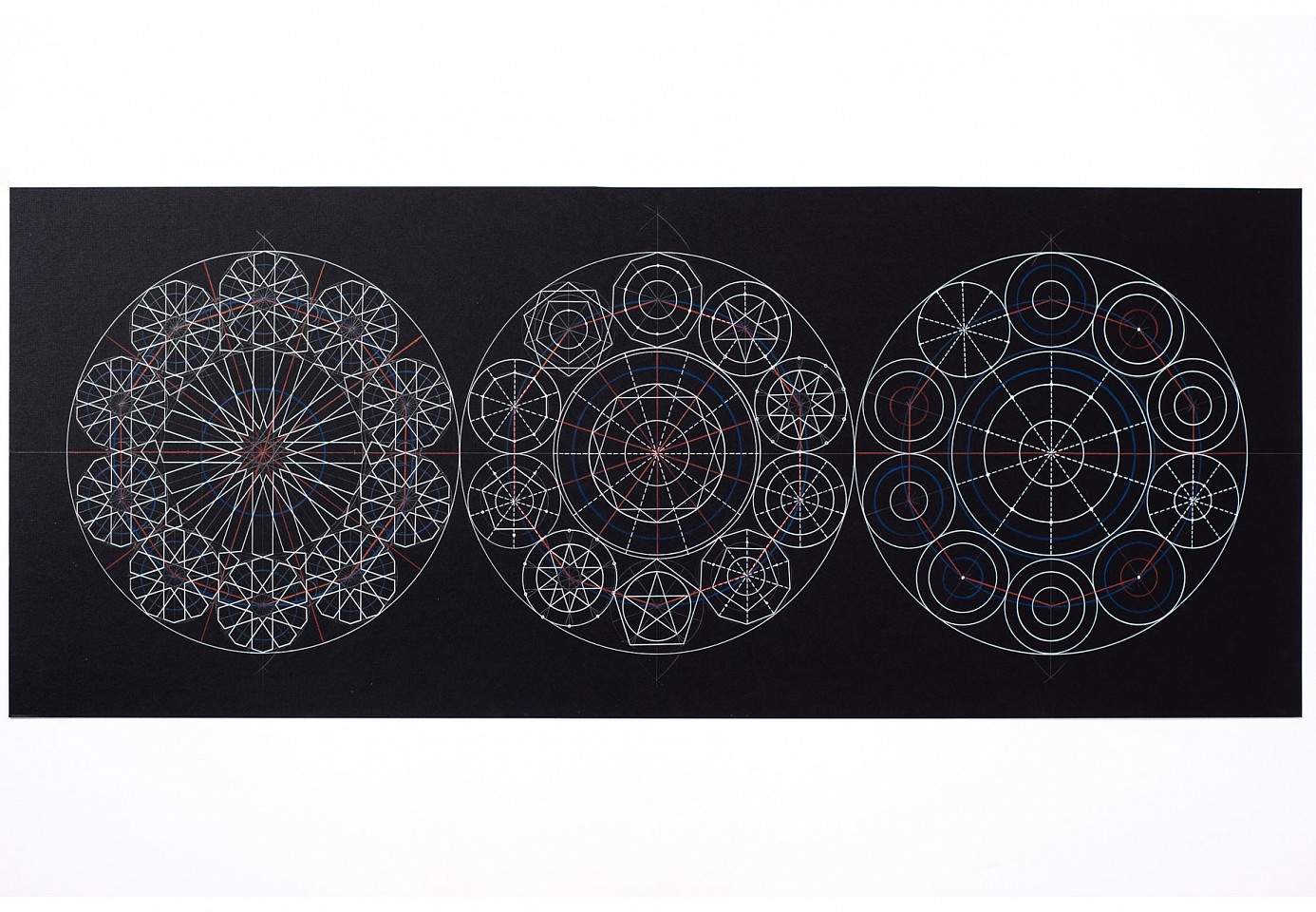

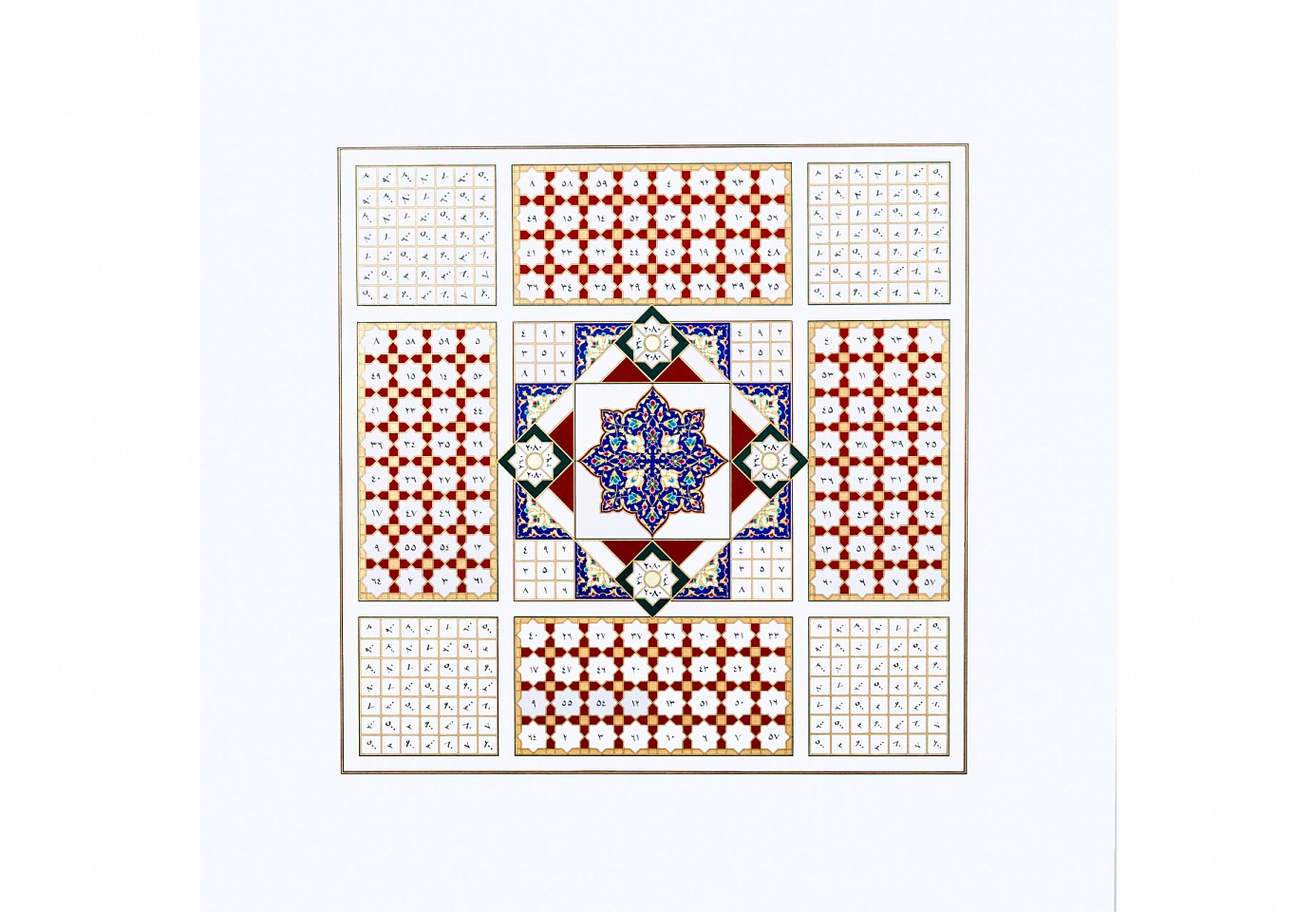

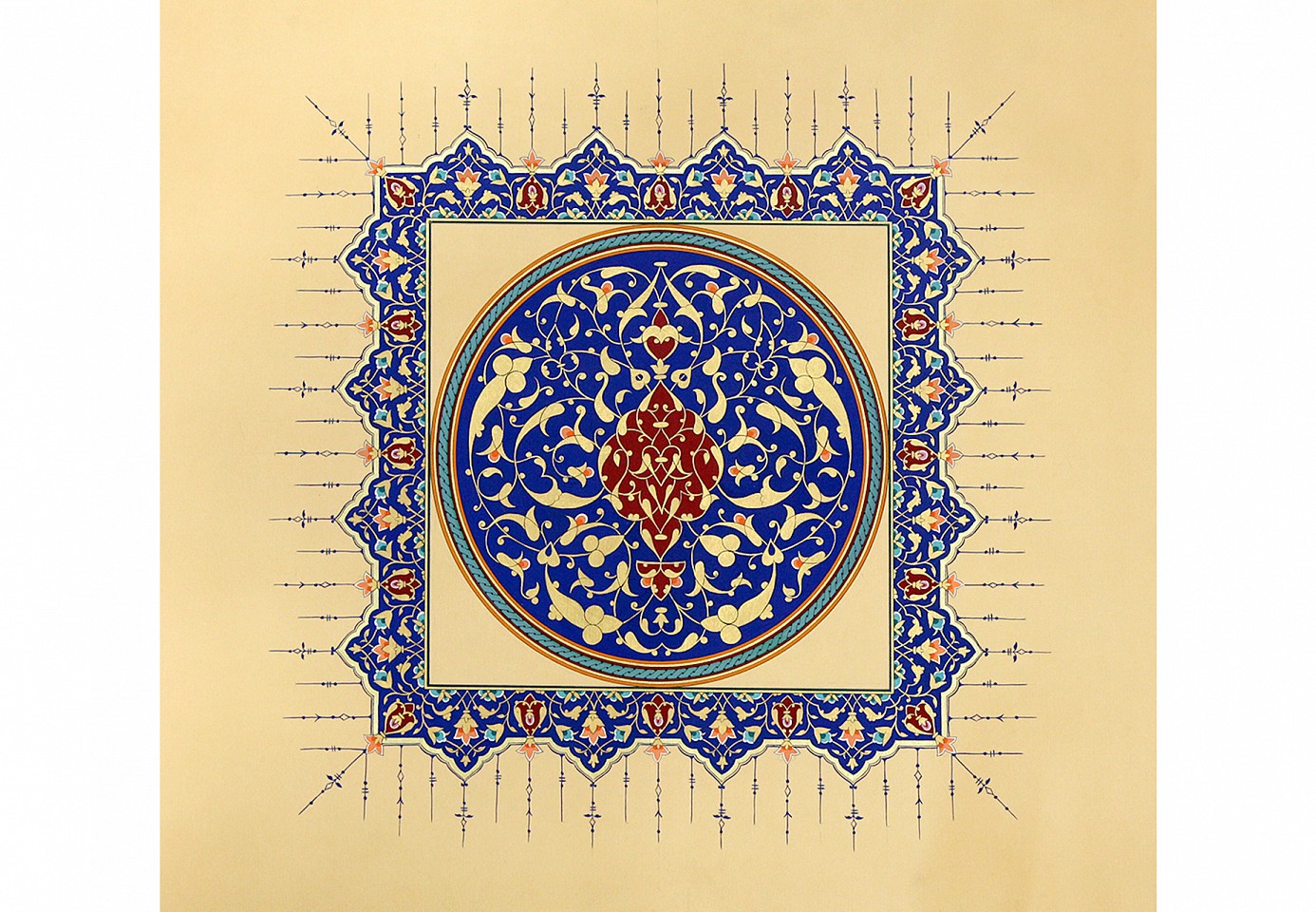

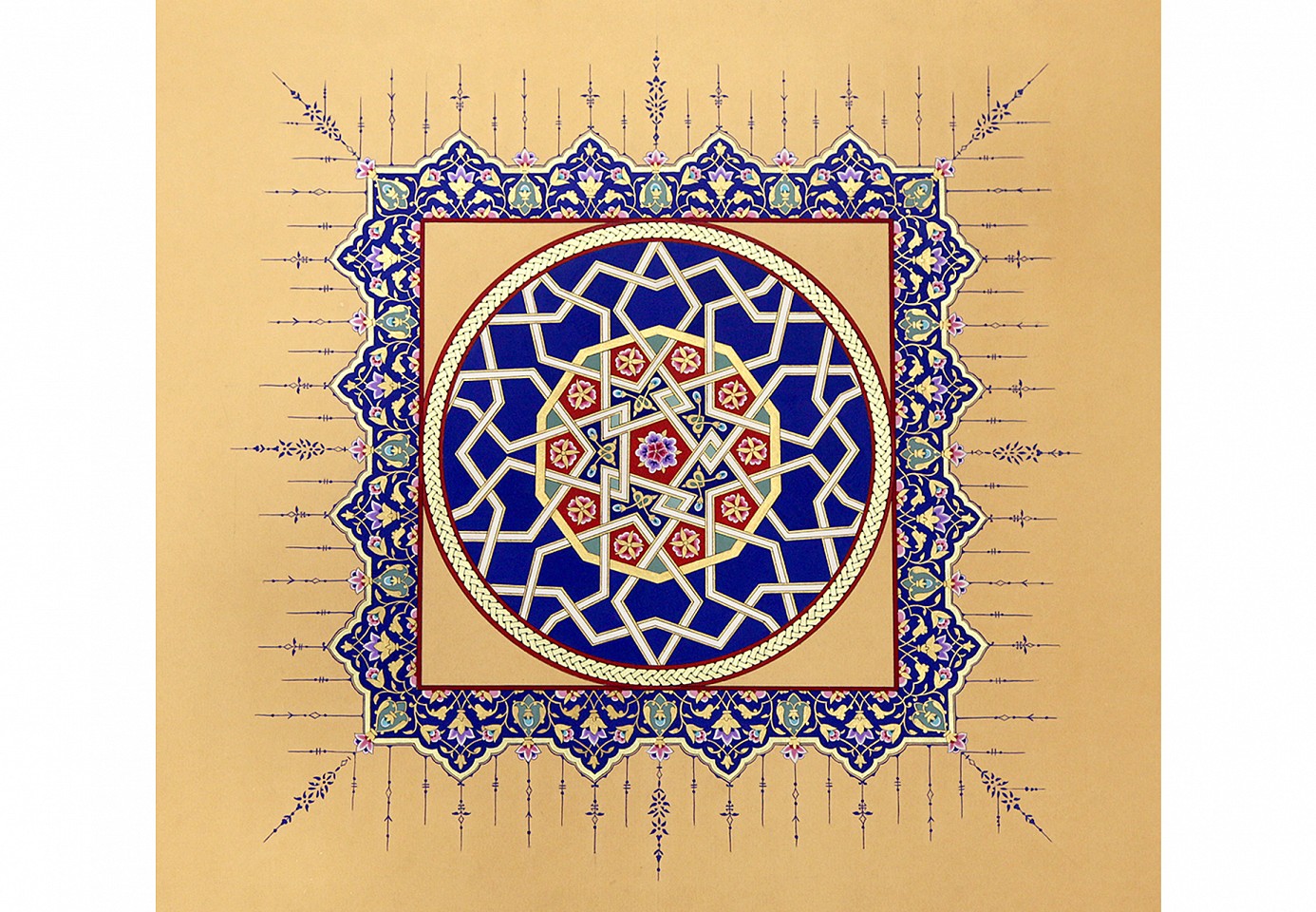

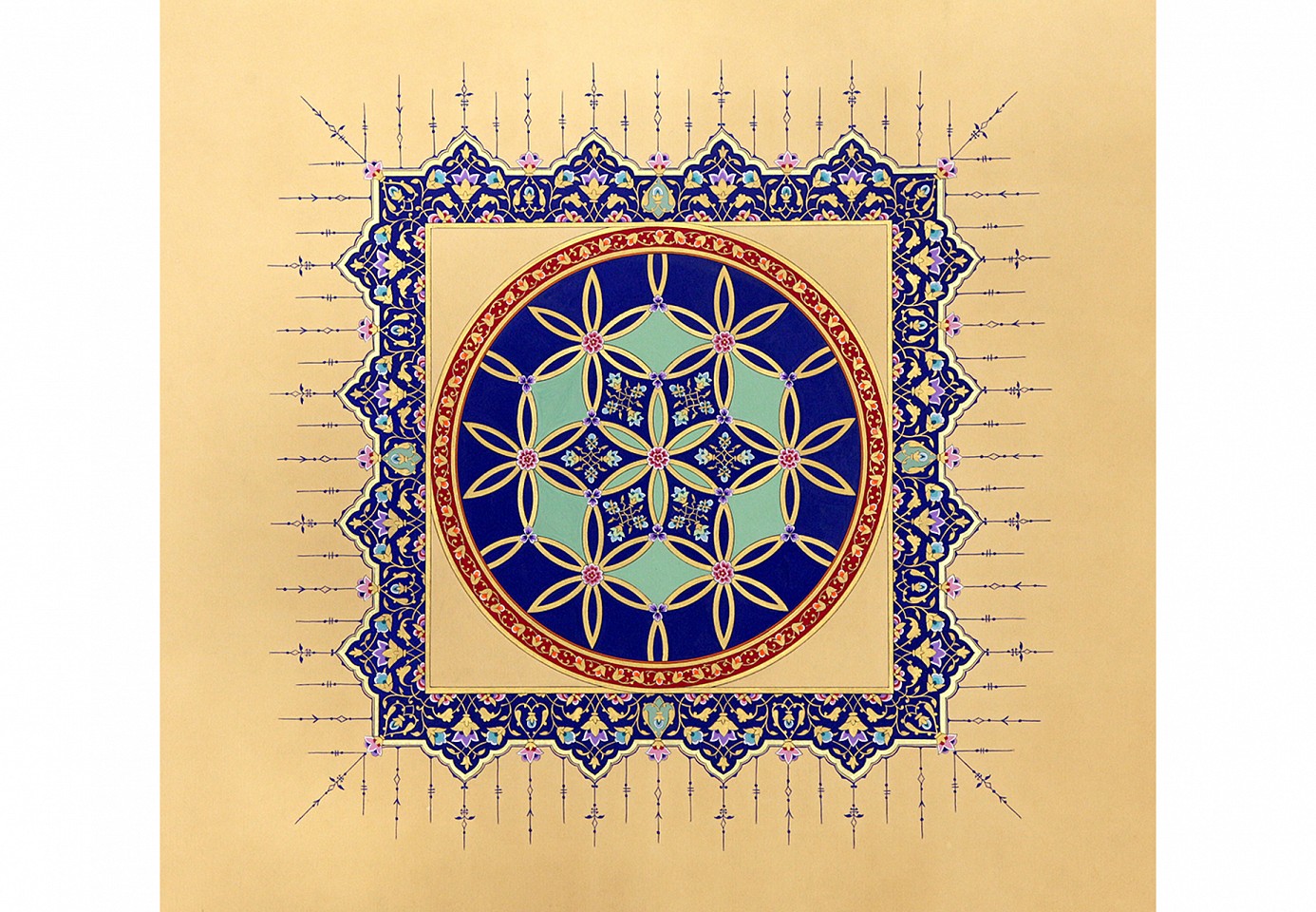

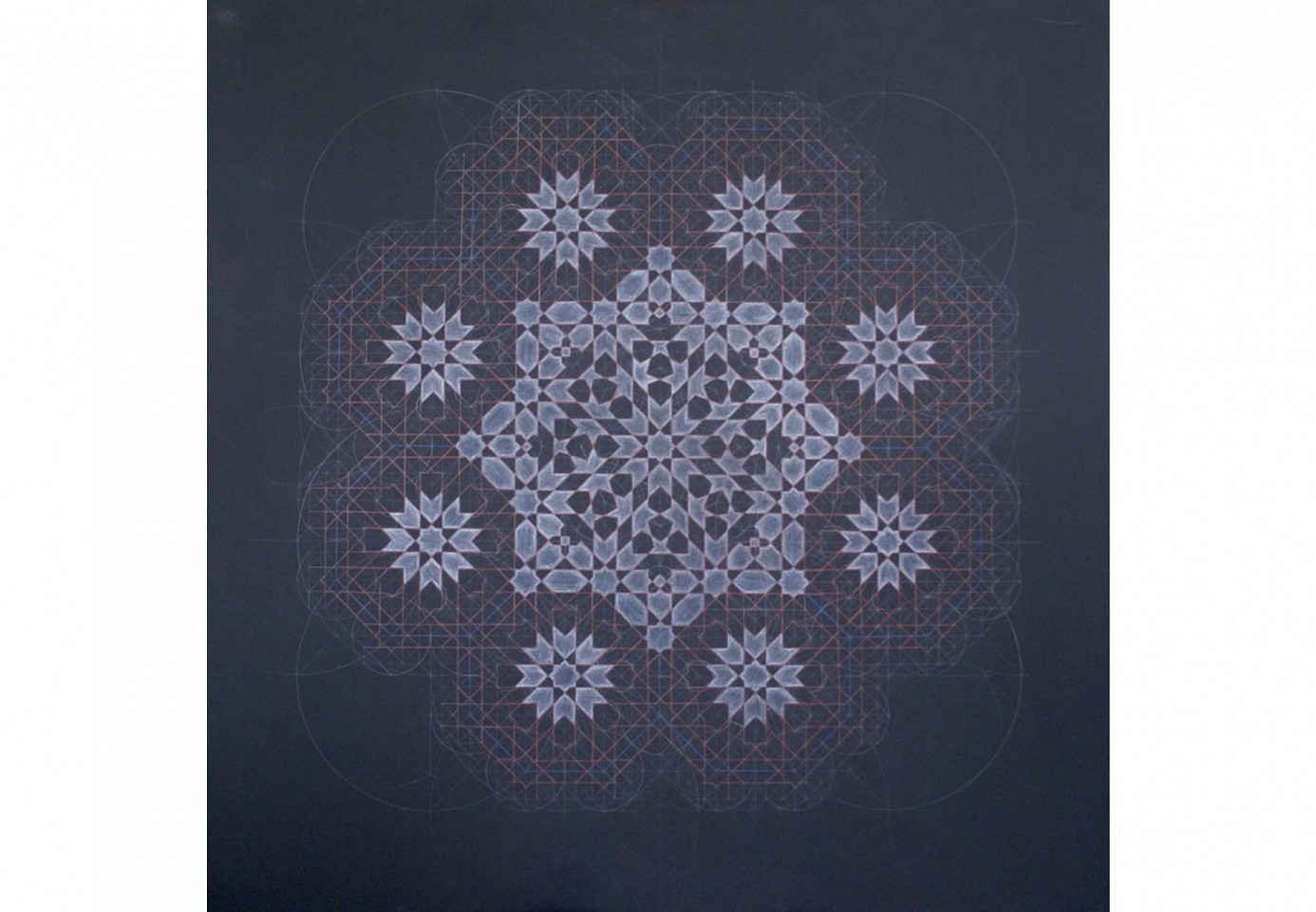

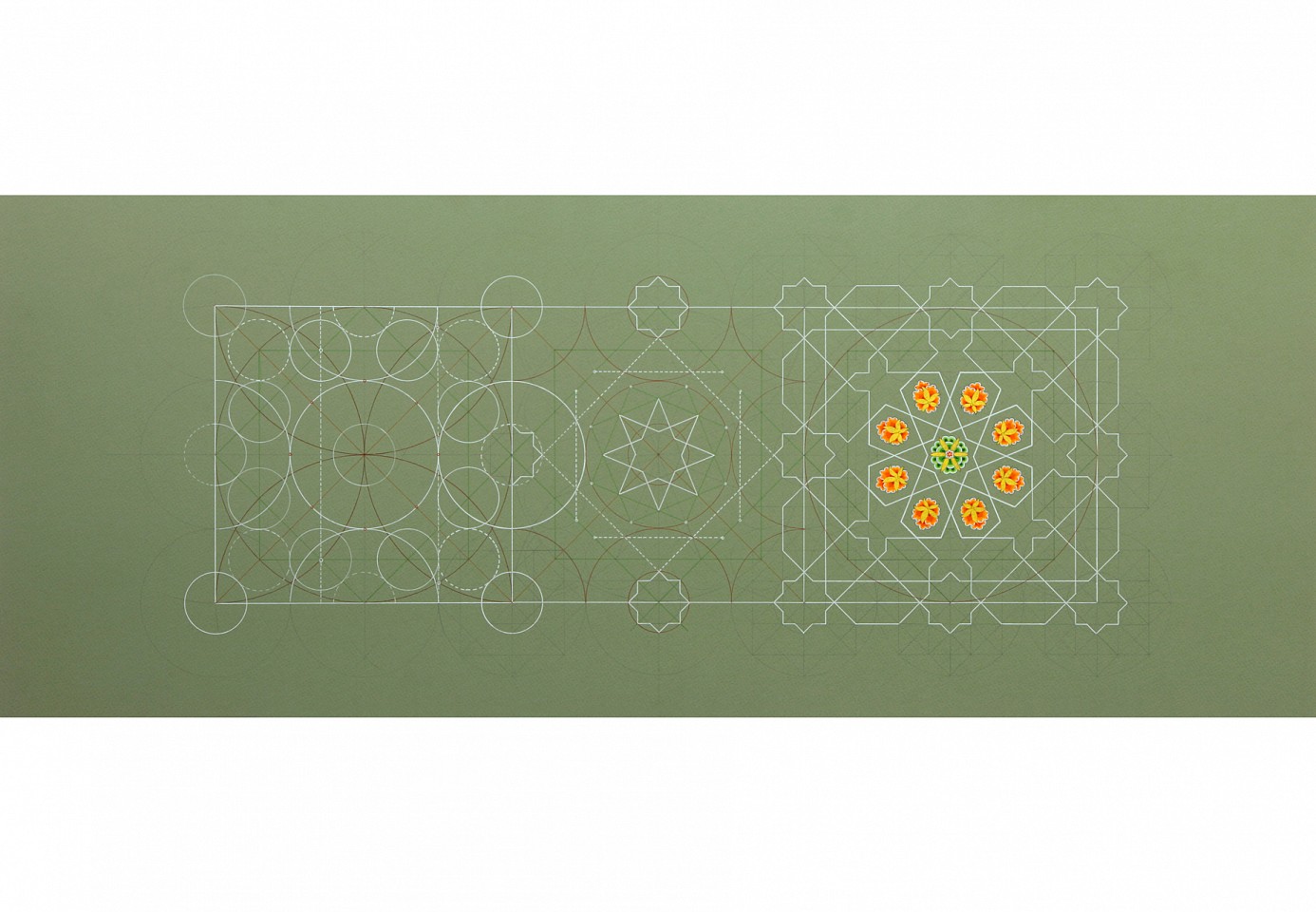

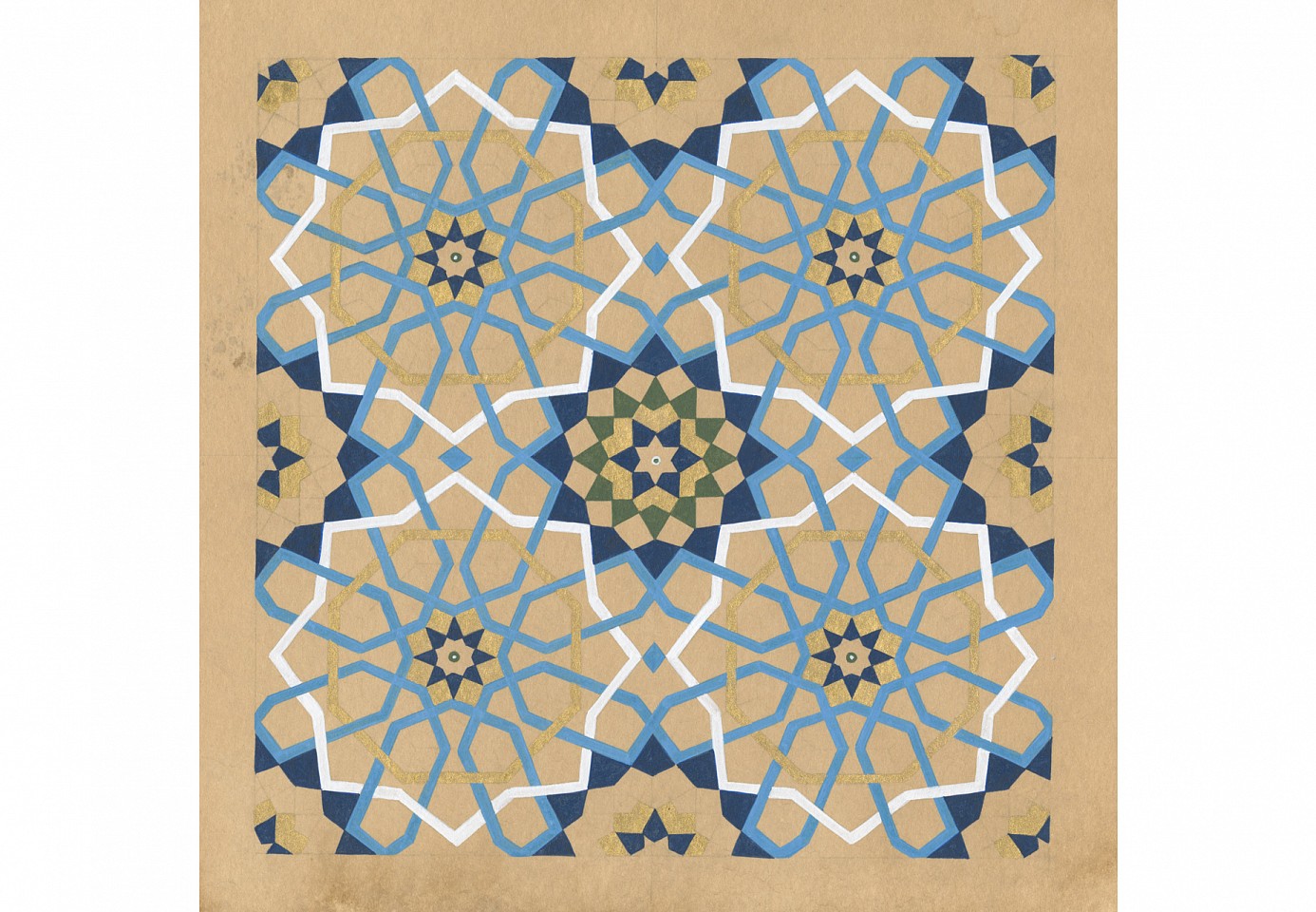

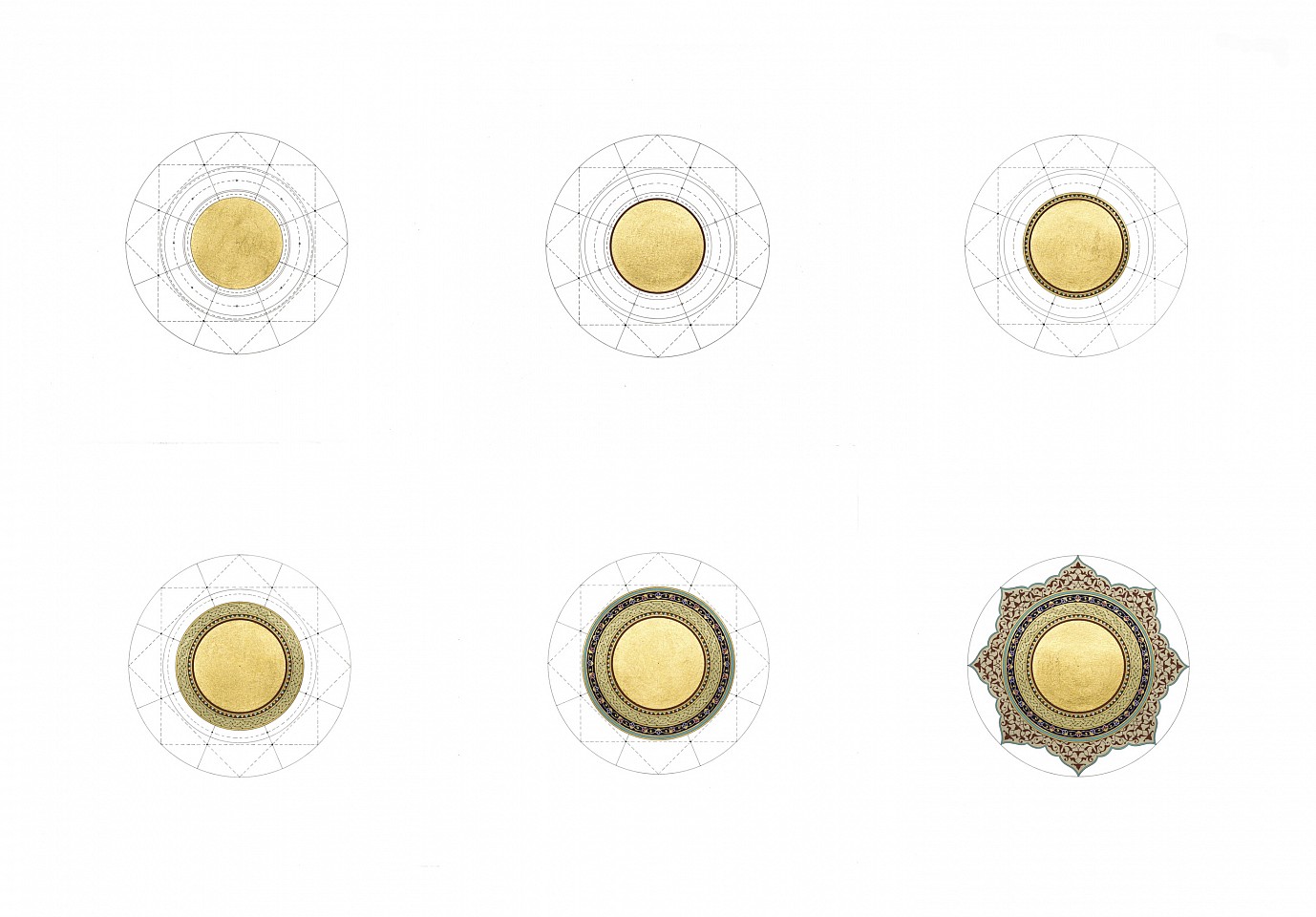

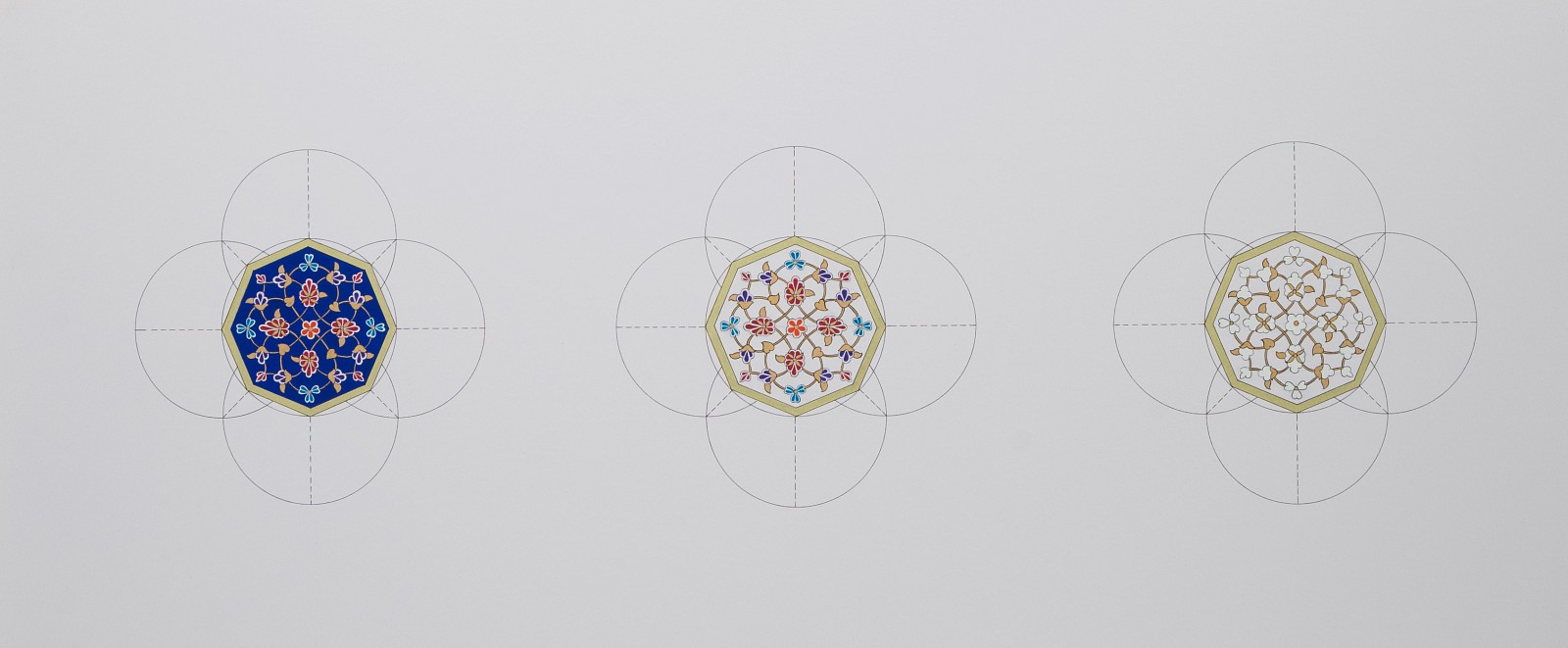

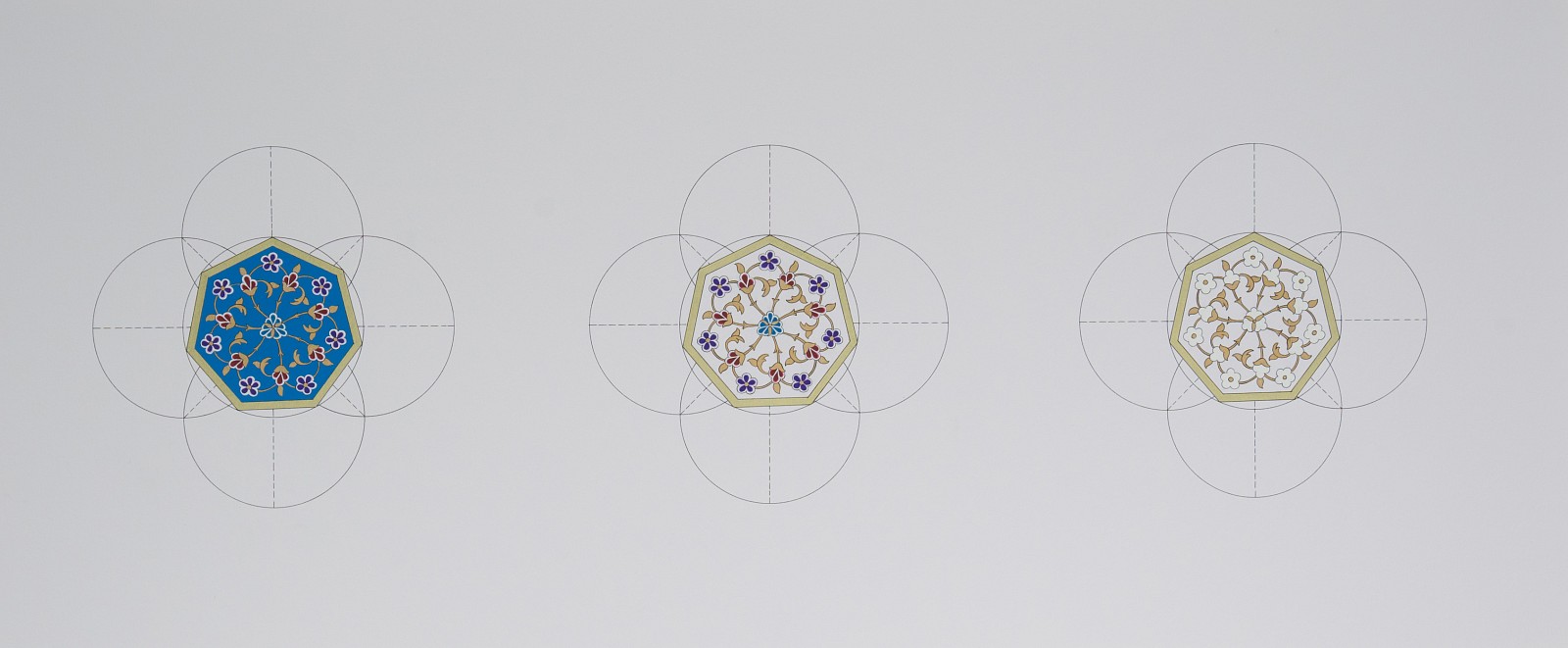

The Islamic Caliphates, 2016

Shell gold and natural pigments on prepared paper

From Left to Right: Rashidun, Umayyad, Late Umayyad, Abbasid, Fatimid, Ayyubid, Mamluk and OttomanÂ

DAN0101

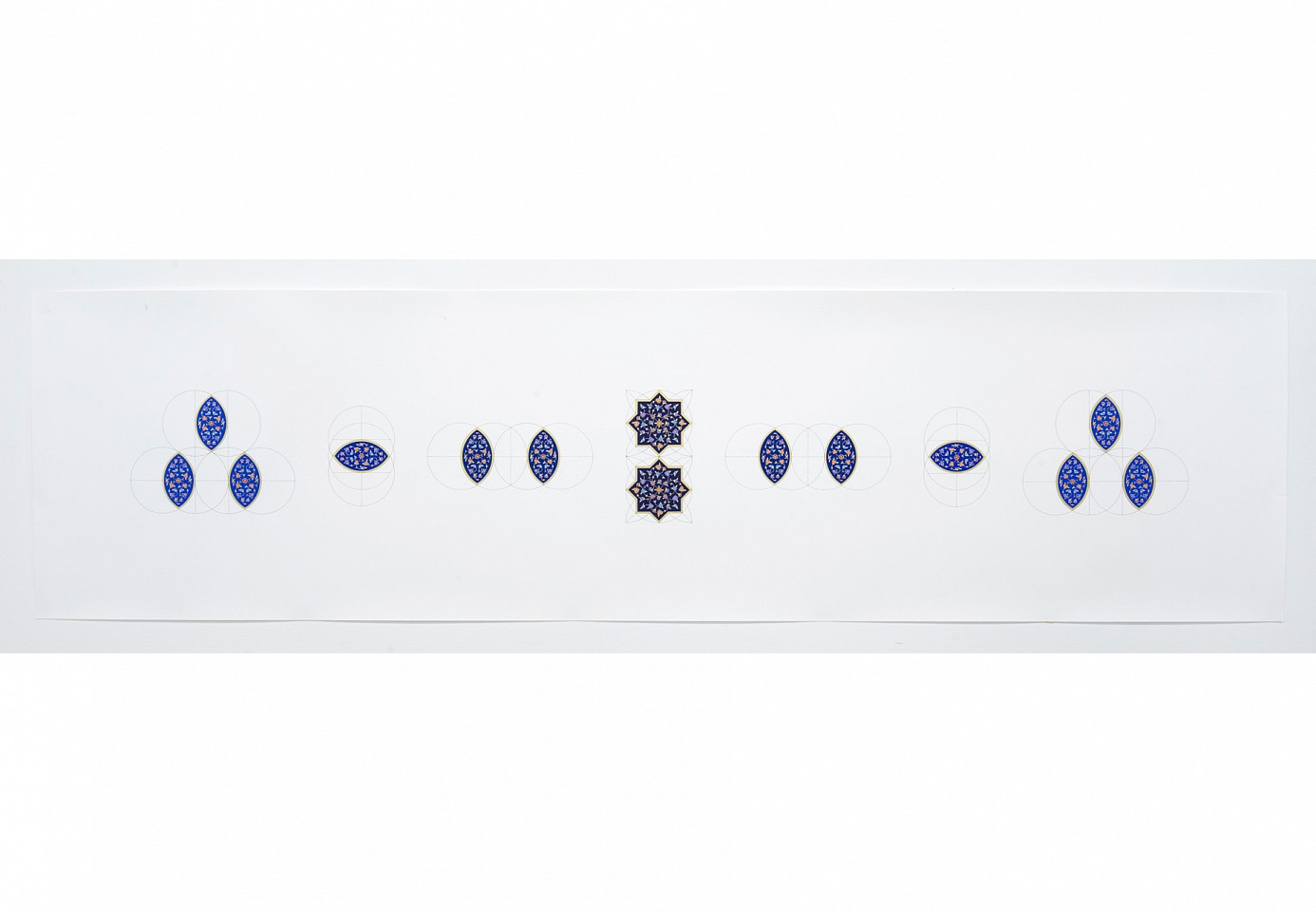

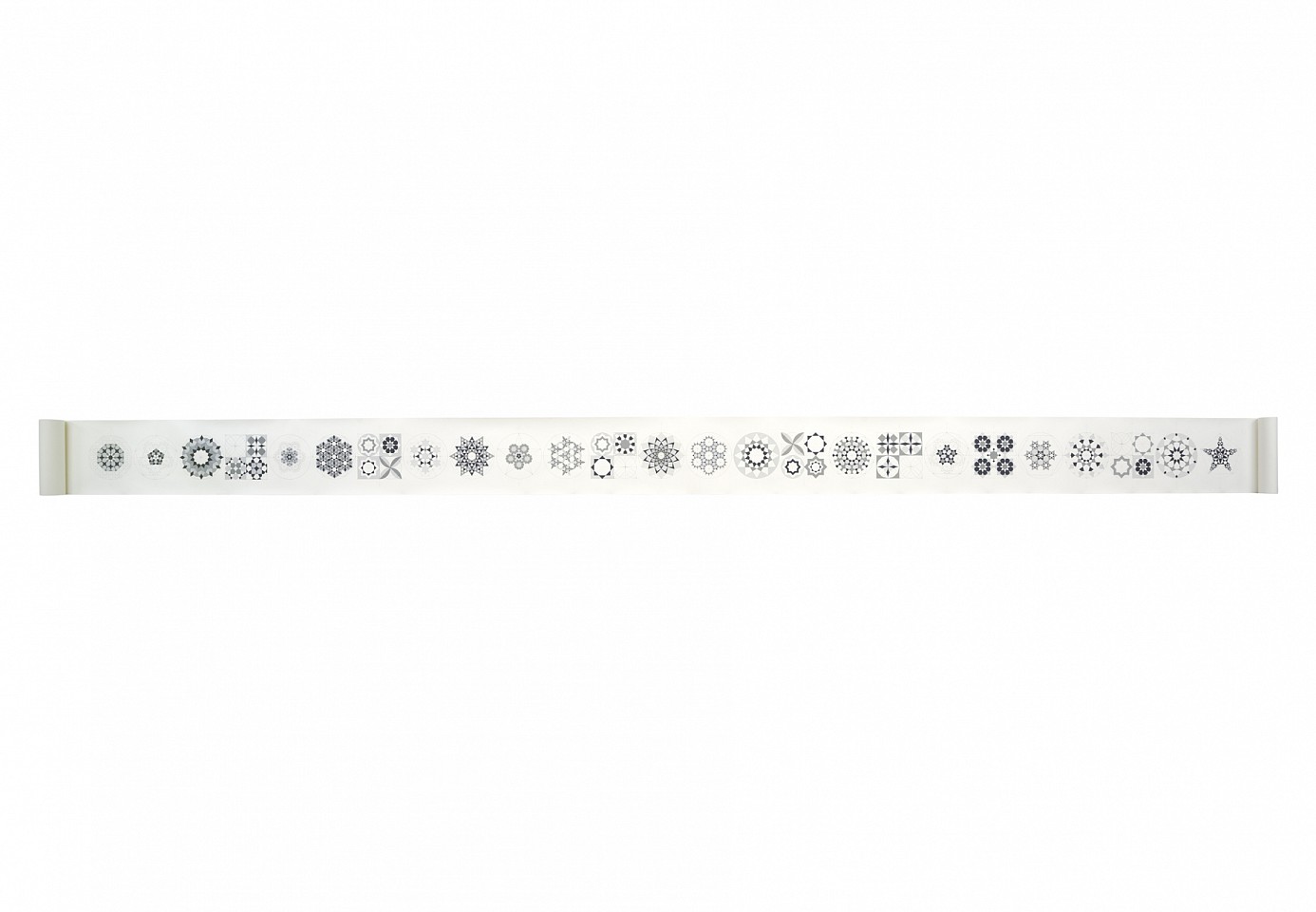

Dana Awartani

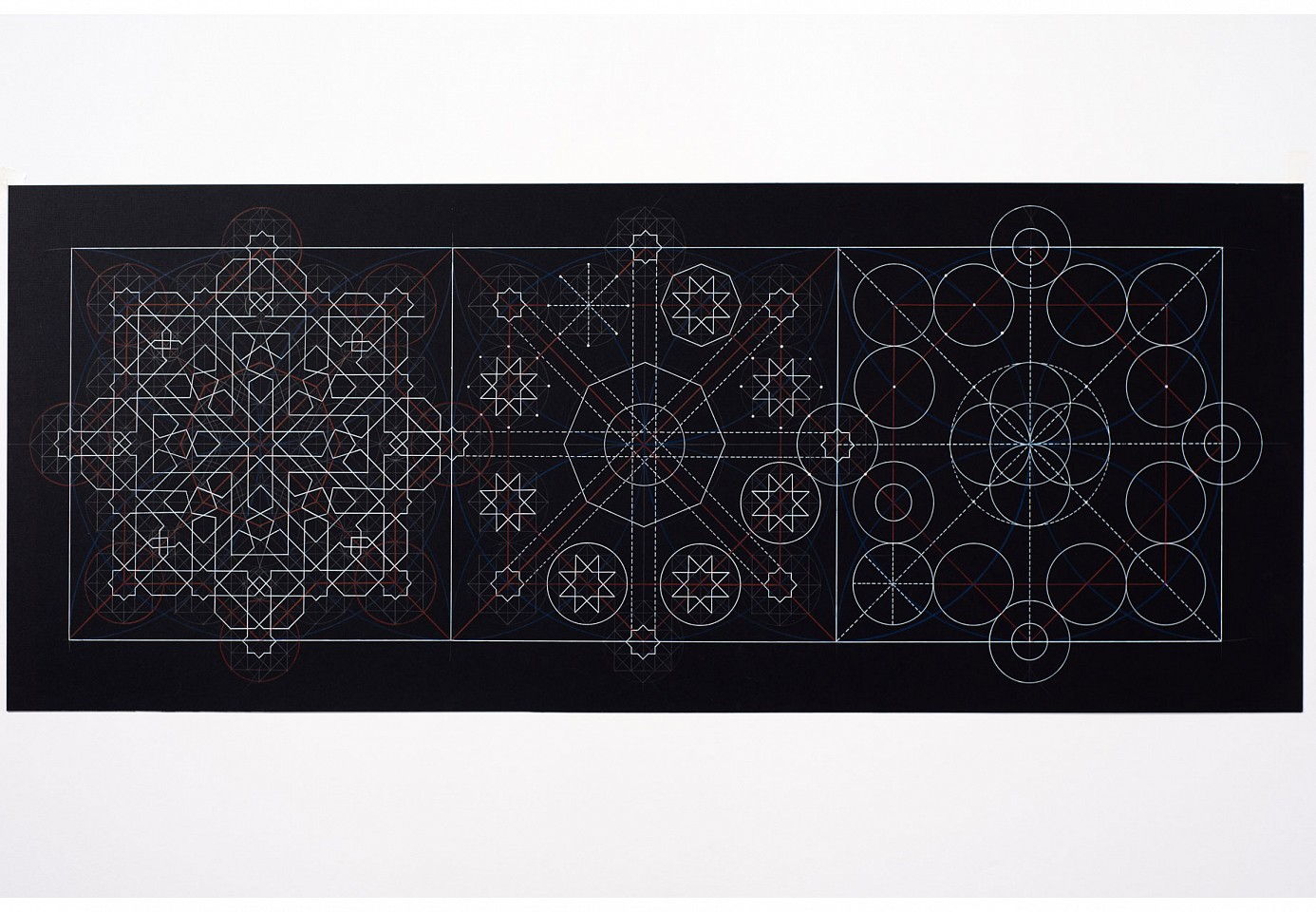

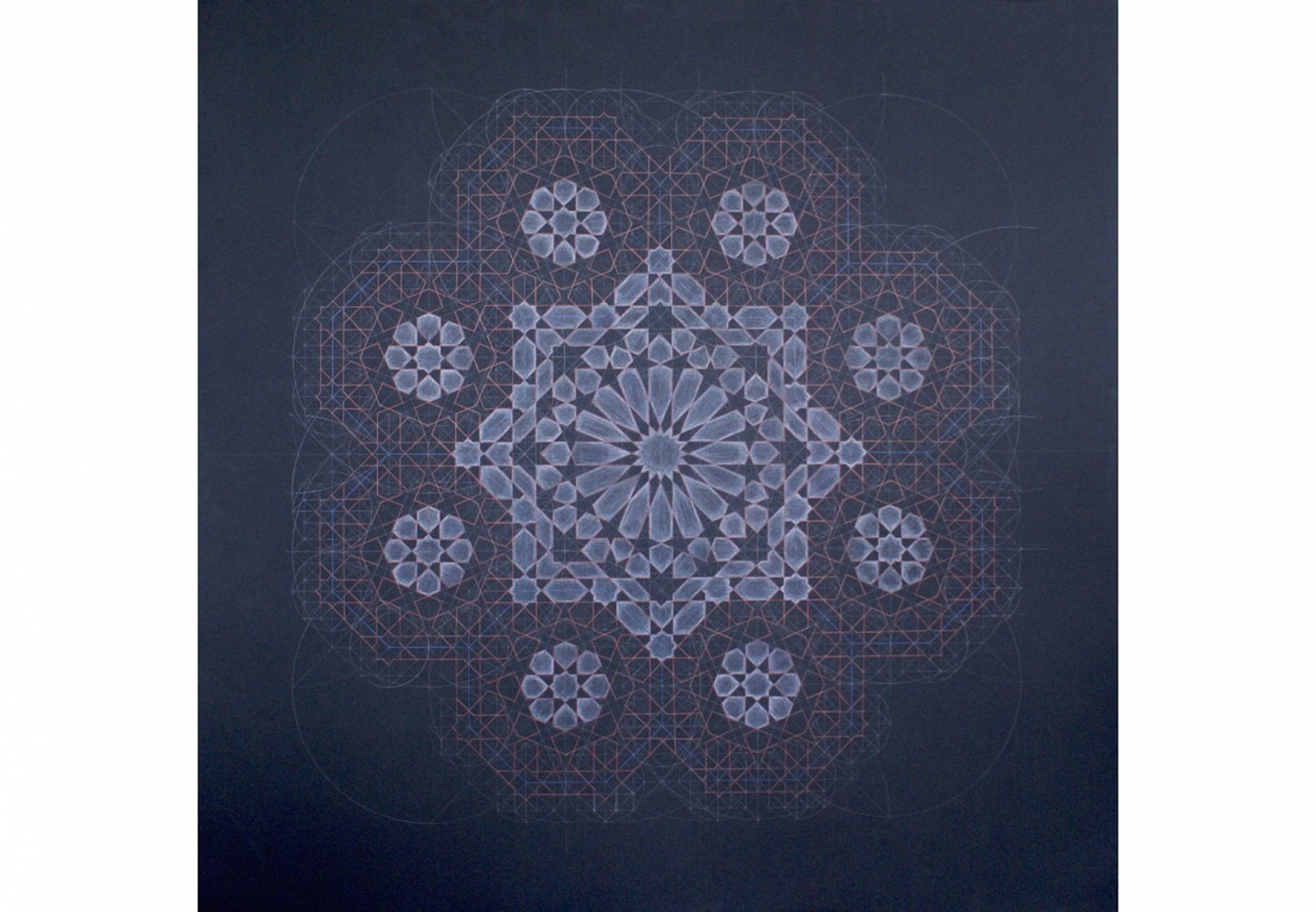

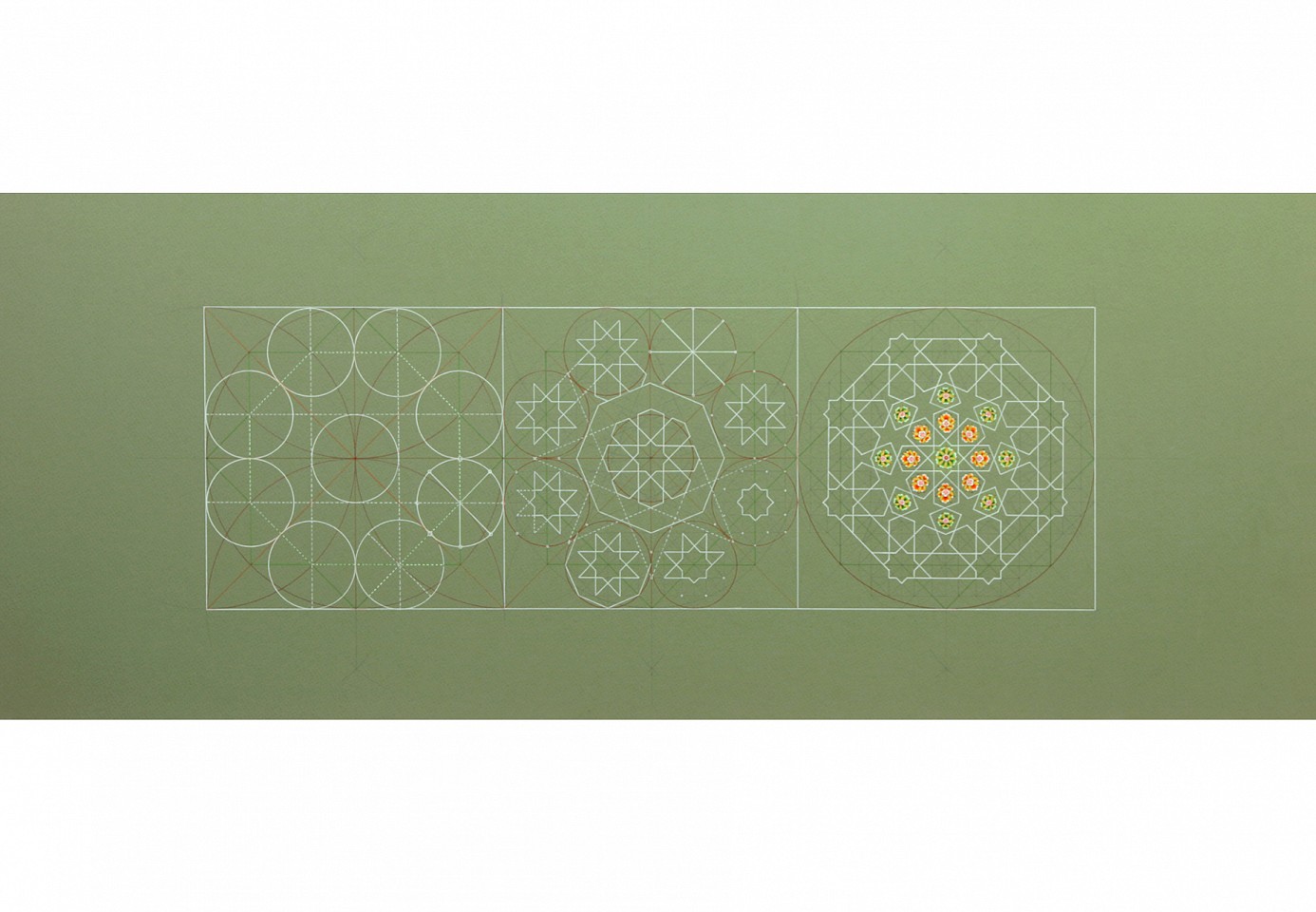

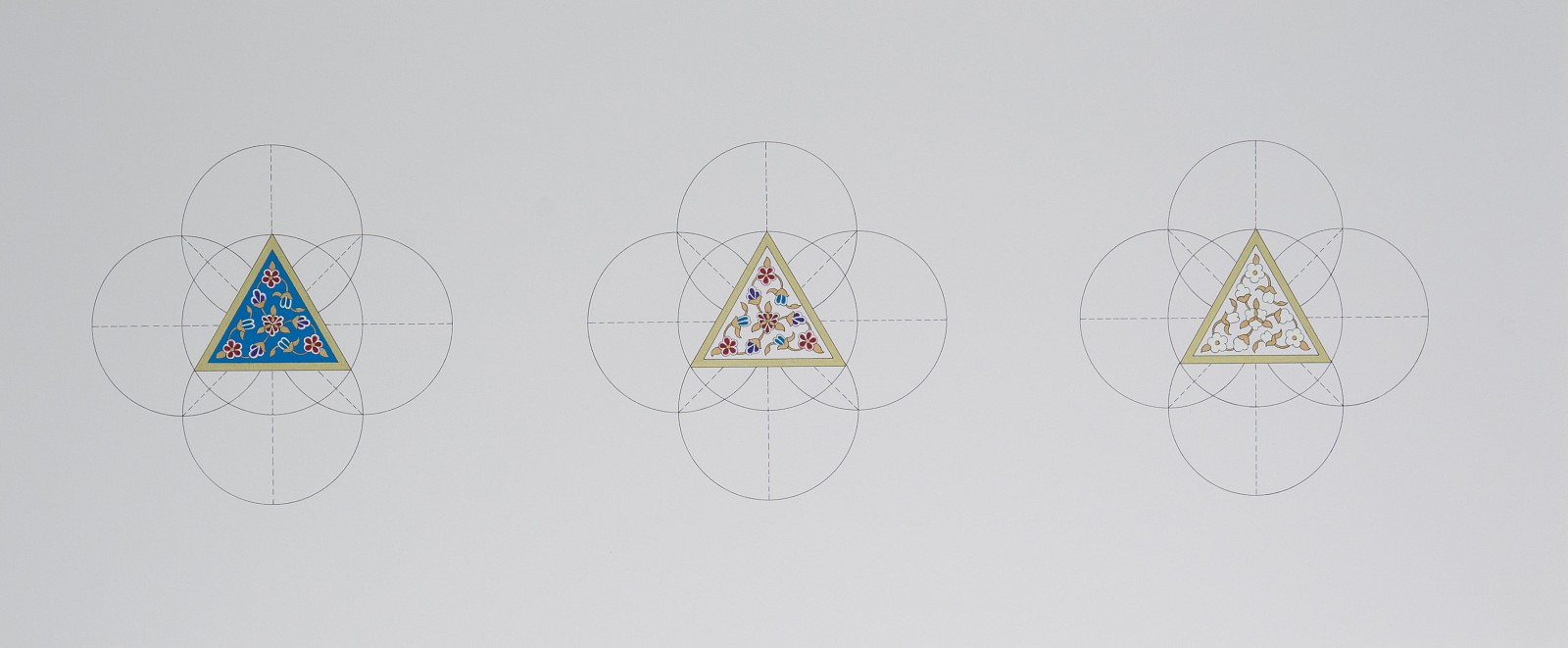

Glorify, 2016

Shell gold, ink and gouache on paper

50 x 190 cm

Dana Awartani

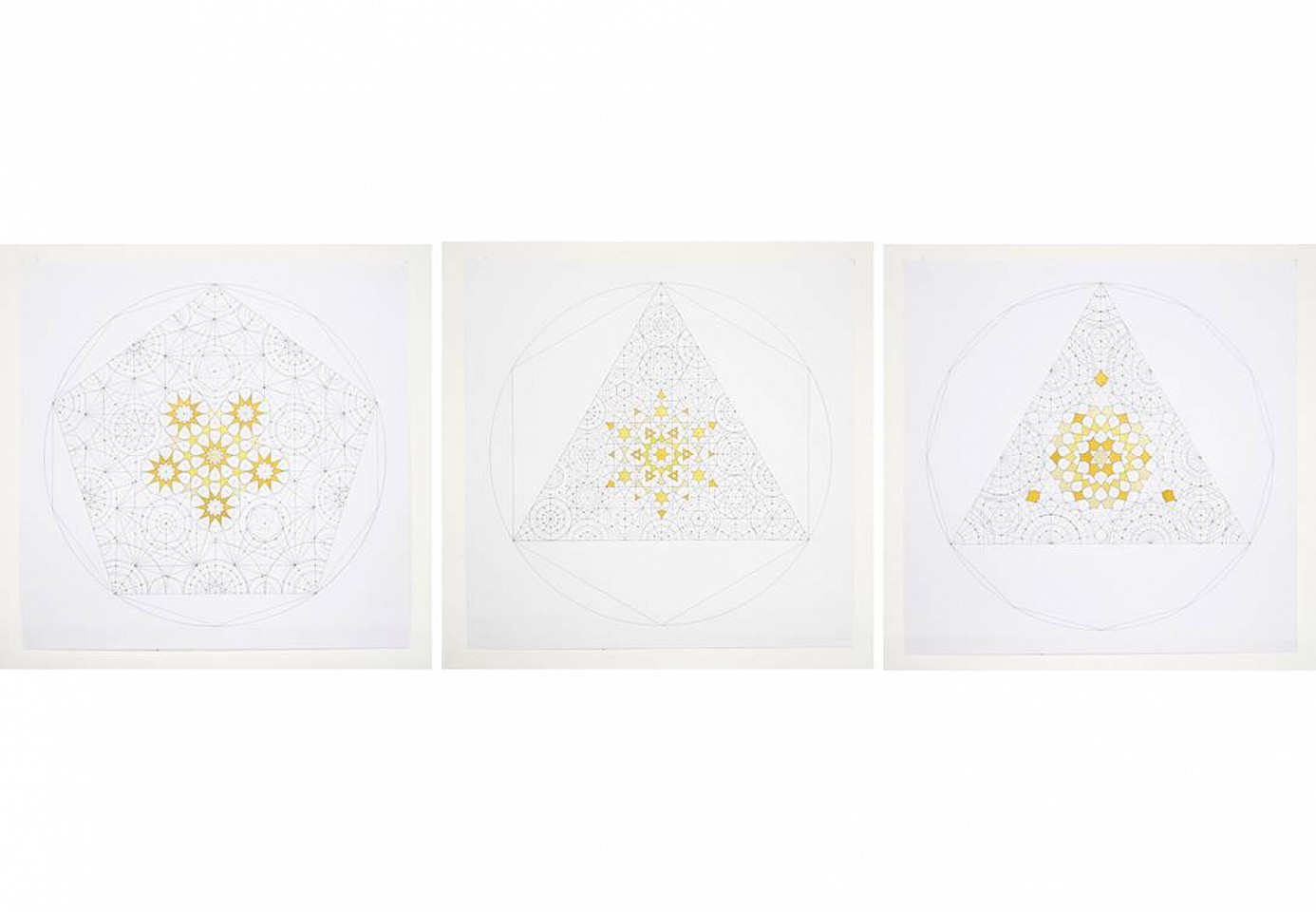

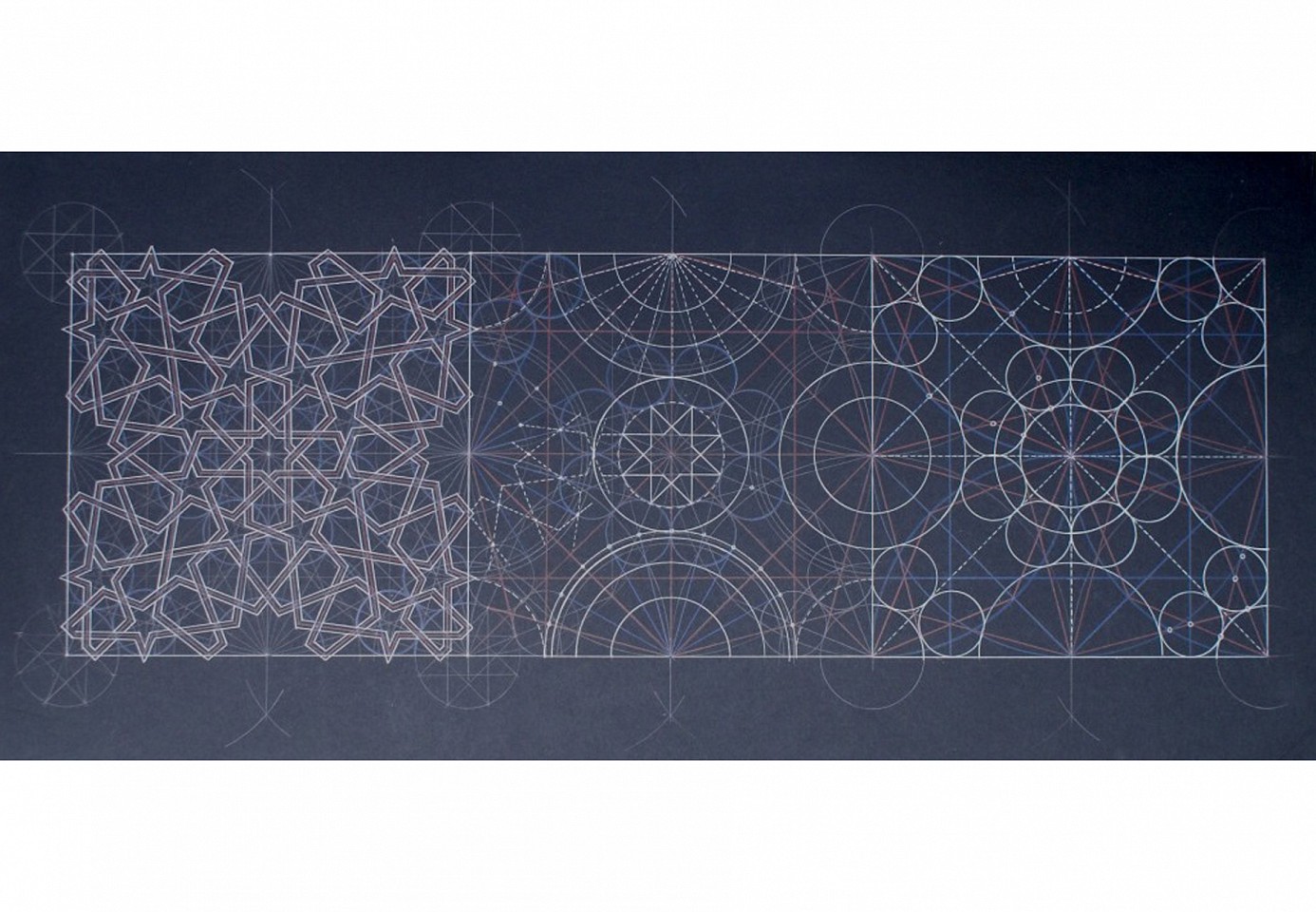

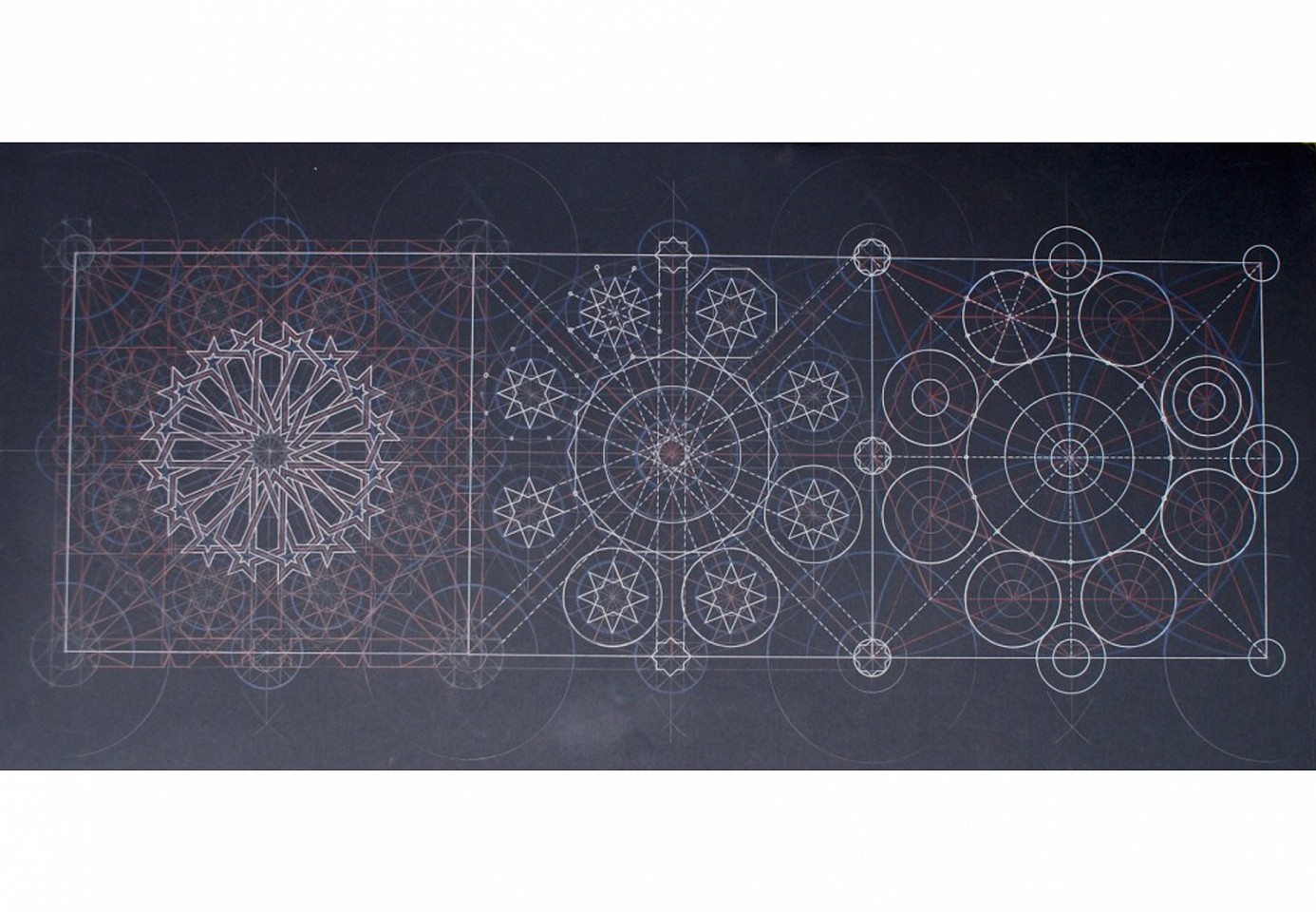

From left to right: Dodecahedron Within an Icosahedron, Octahedron Within a Cube & Icosahedron within a Dodecahedron from The Platonic Solid Duals Series, 2016

Shell gold and ink on paper

DAN0112

Dana Awartani

The Platonic Solid Duals Series, 2016

Wood, copper and glass

From left to right: Dodecahedron Within a Icosahedron, Octahedron Within a Cube and Icosahedron Within a Dodecahedron

DAN0106

Dana Awartani

Acceptance from the Five Stages of Grief series, 2015

Embroidery on cotton

85 x 144 cm (33 7/16 x 56 11/16 in.)

DAN0070

Dana Awartani

Anger from the Five Stages of Grief series, 2015

Embroidery on cotton

85 x 144 cm (33 7/16 x 56 11/16 in.)

DAN0071

Dana Awartani

Bargaining from the Five Stages of Grief series, 2015

Embroidery on cotton

85 x 144 cm (33 7/16 x 56 11/16 in.)

DAN0072

Dana Awartani

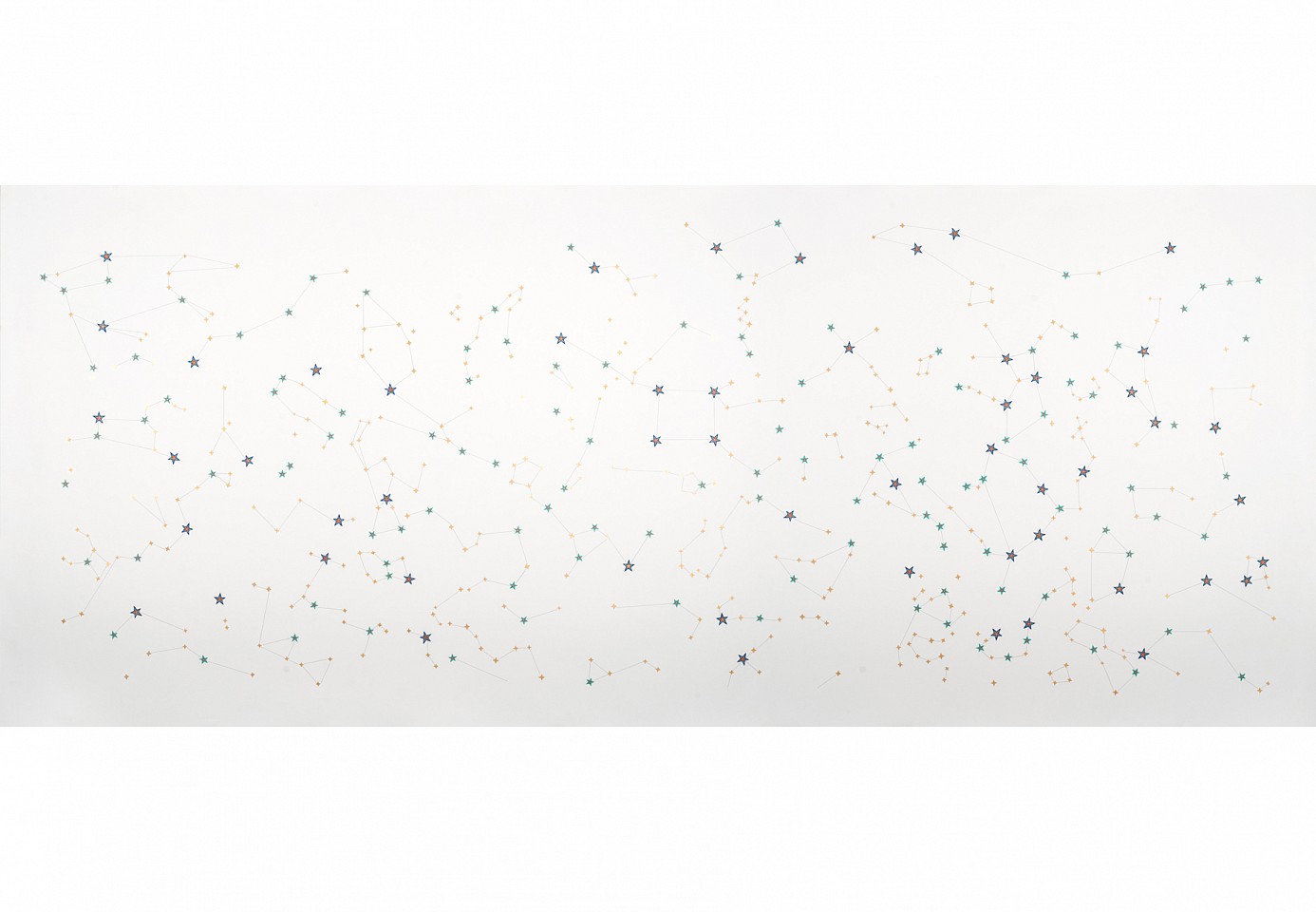

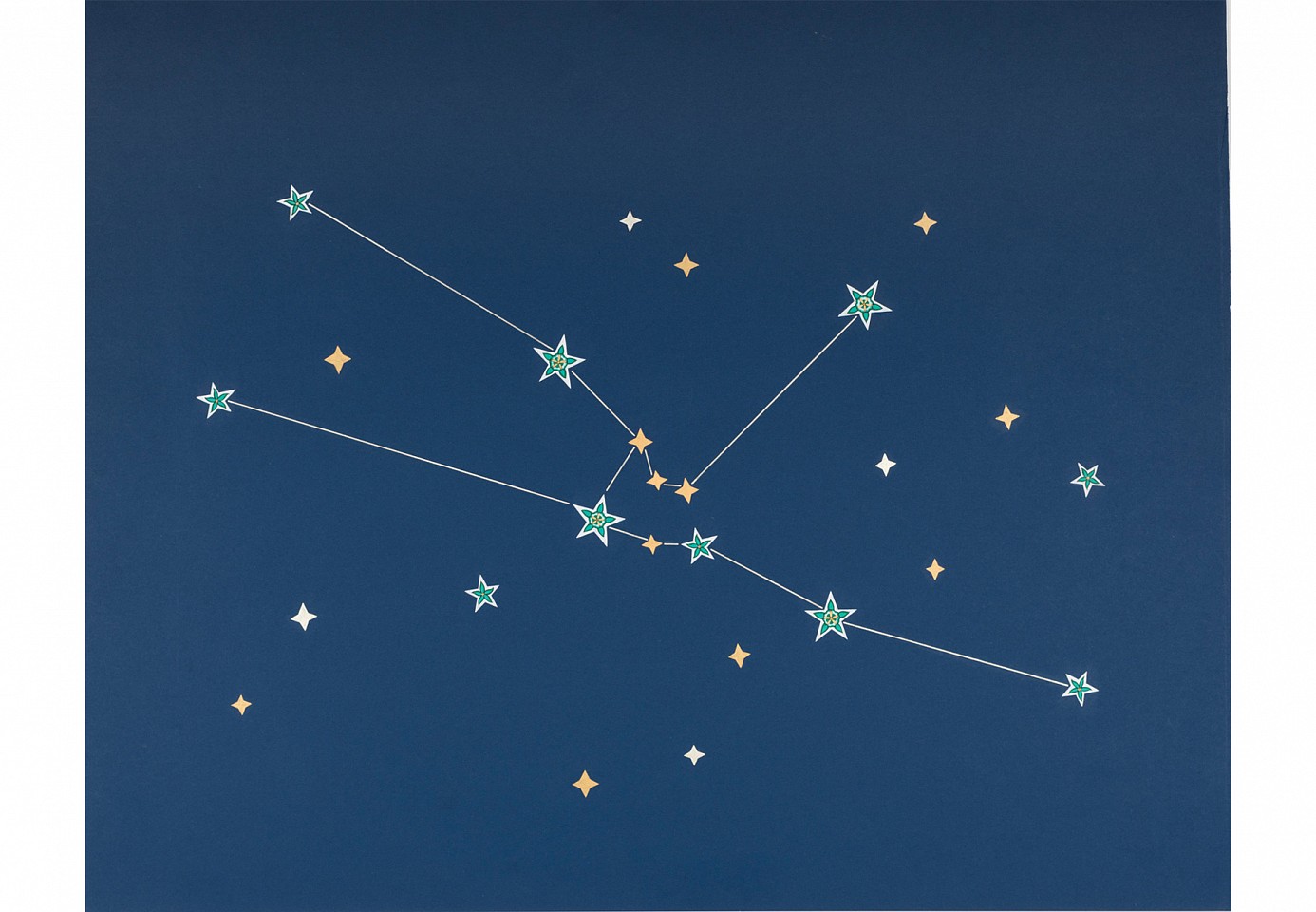

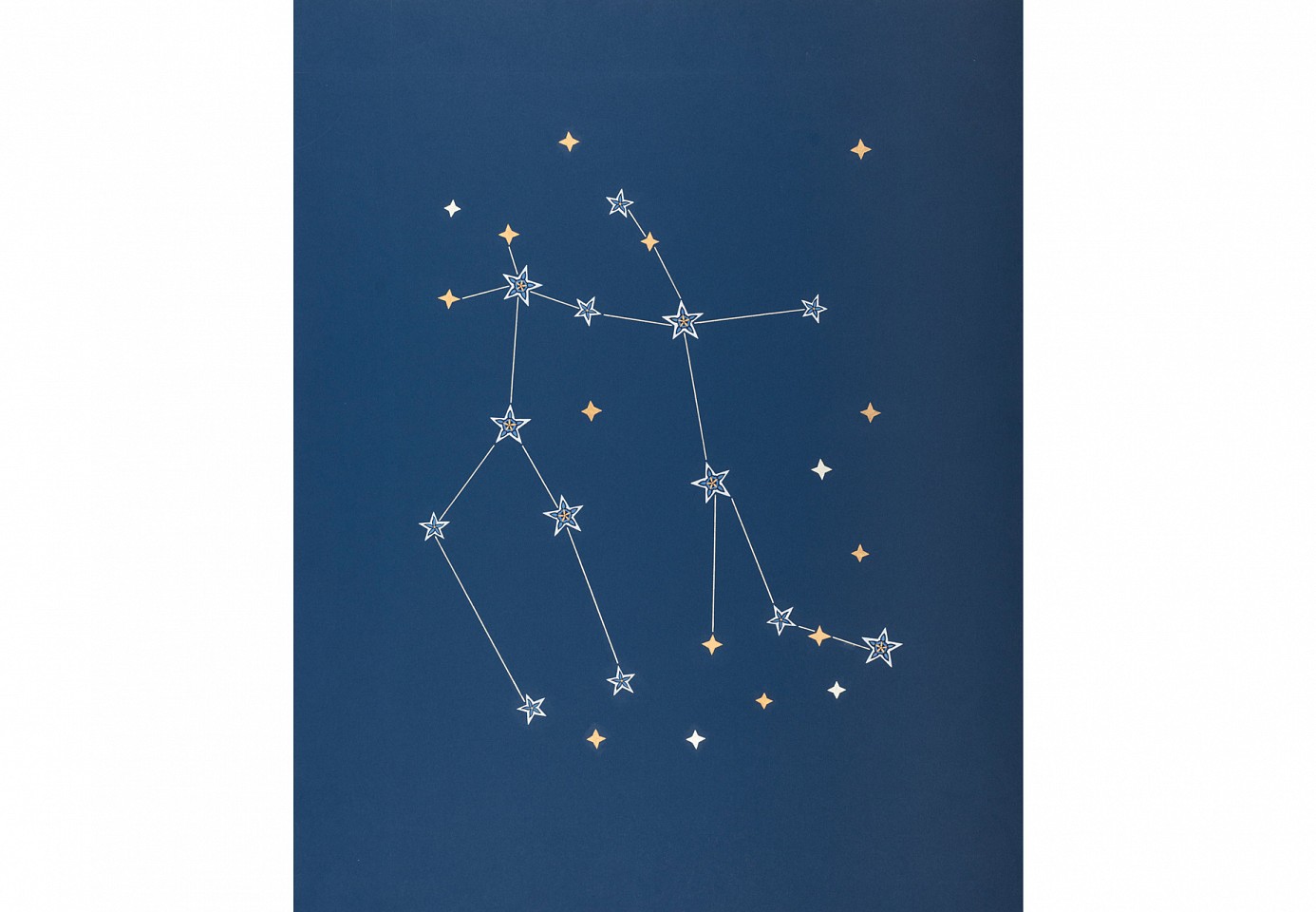

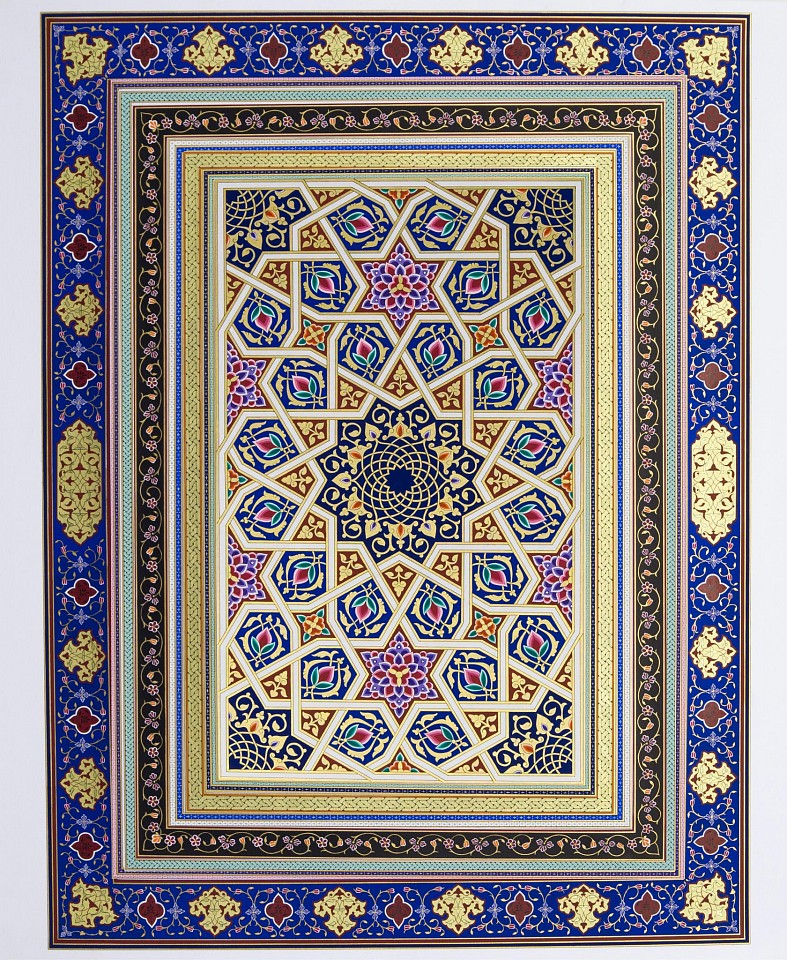

A Symphony of Stars, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

96 x 228 cm (37 3/4 x 89 3/4 in.)

DAN0069

Dana Awartani

Moses, 2014

Work on paper

113.5 x 118 cm (44 5/8 x 46 7/16 in.)

From the Seal of Prophets series

DAN0060

Dana Awartani

Jesus, 2014

Work on paper

113.5 x 118 cm (44 5/8 x 46 7/16 in.)

From the Seal of Prophets series

DAN0061

Dana Awartani

Mohammad, 2014

Work on paper

113.5 x 118 cm (44 5/8 x 46 7/16 in.)

From the Seal of Prophets series

DAN0062

Dana Awartani

Progressional Drawing #11, 2014

Gel pen and colored pencil on paper

50 x 100 cm (19 5/8 x 39 5/16 in.)

DAN0058

Dana Awartani

Progressional Drawing #12, 2014

Gel pen and colored pencil on paper

50 x 100 cm (19 5/8 x 39 5/16 in.)

DAN0059

Dana Awartani

He Is Who Created The Heavens and Earth In Six Days, 2013

Natural pigments on paper

DAN0035

Dana Awartani

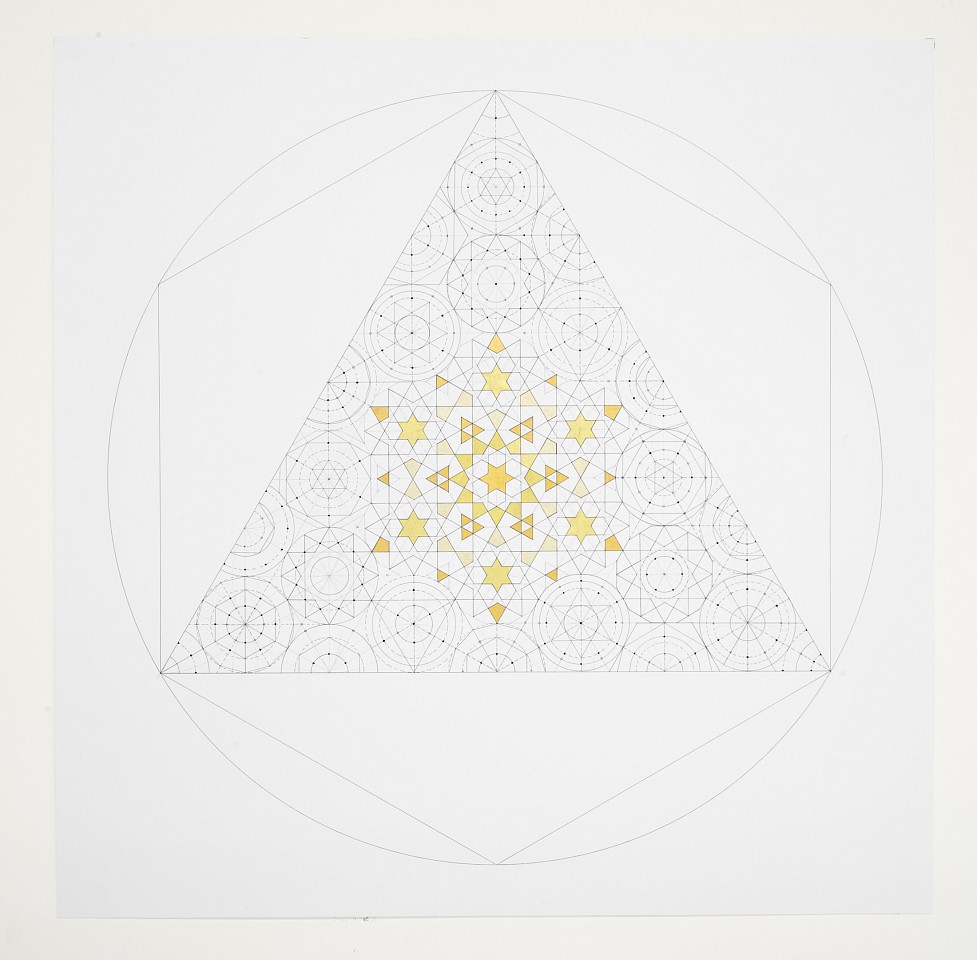

Tetrahedron (Fire), 2014

Pencil & national pigments on mount board

81 x 81 cm (31 7/8 x 31 7/8 in.)

From the Platonic Solids series

DAN0040

Dana Awartani

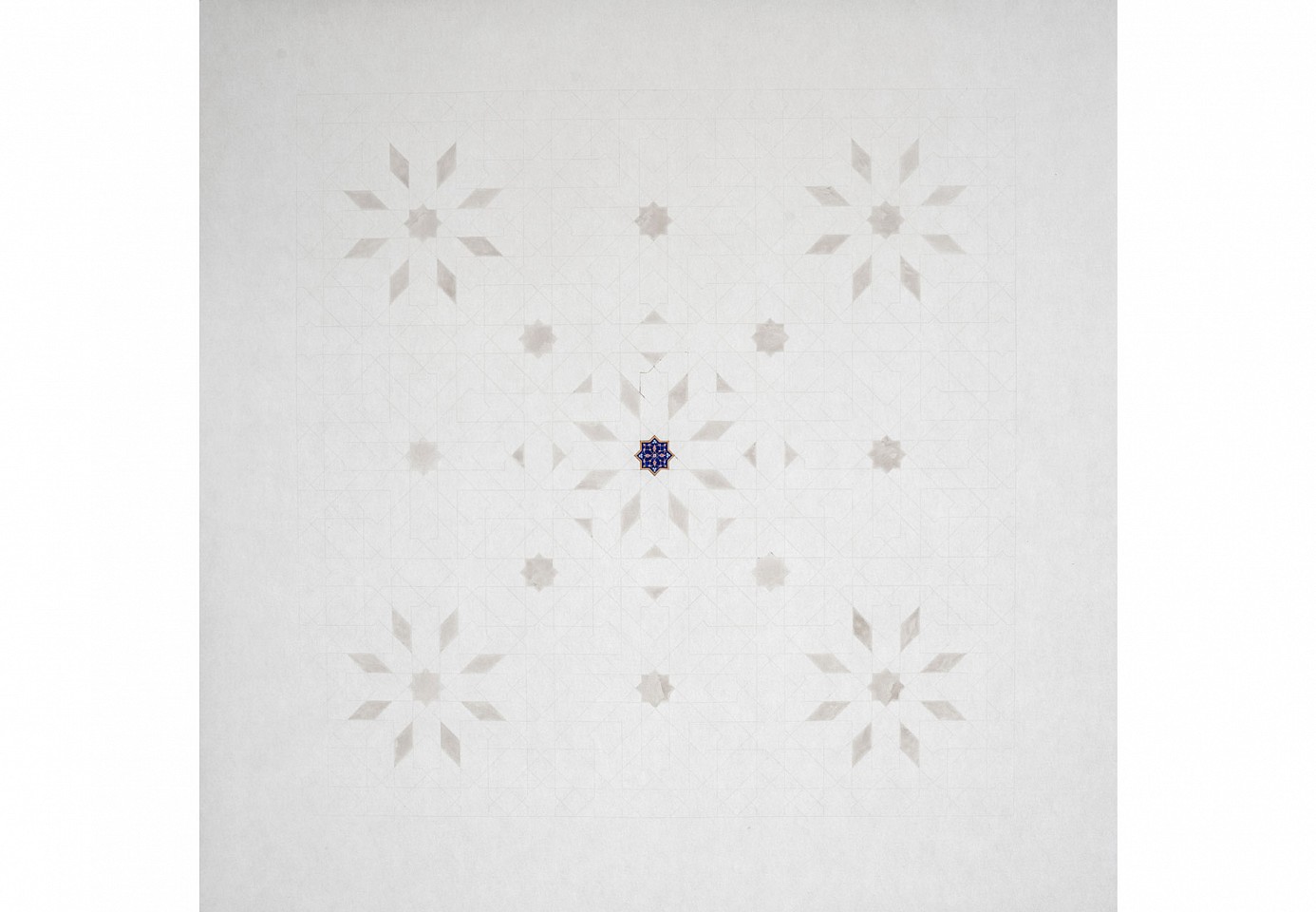

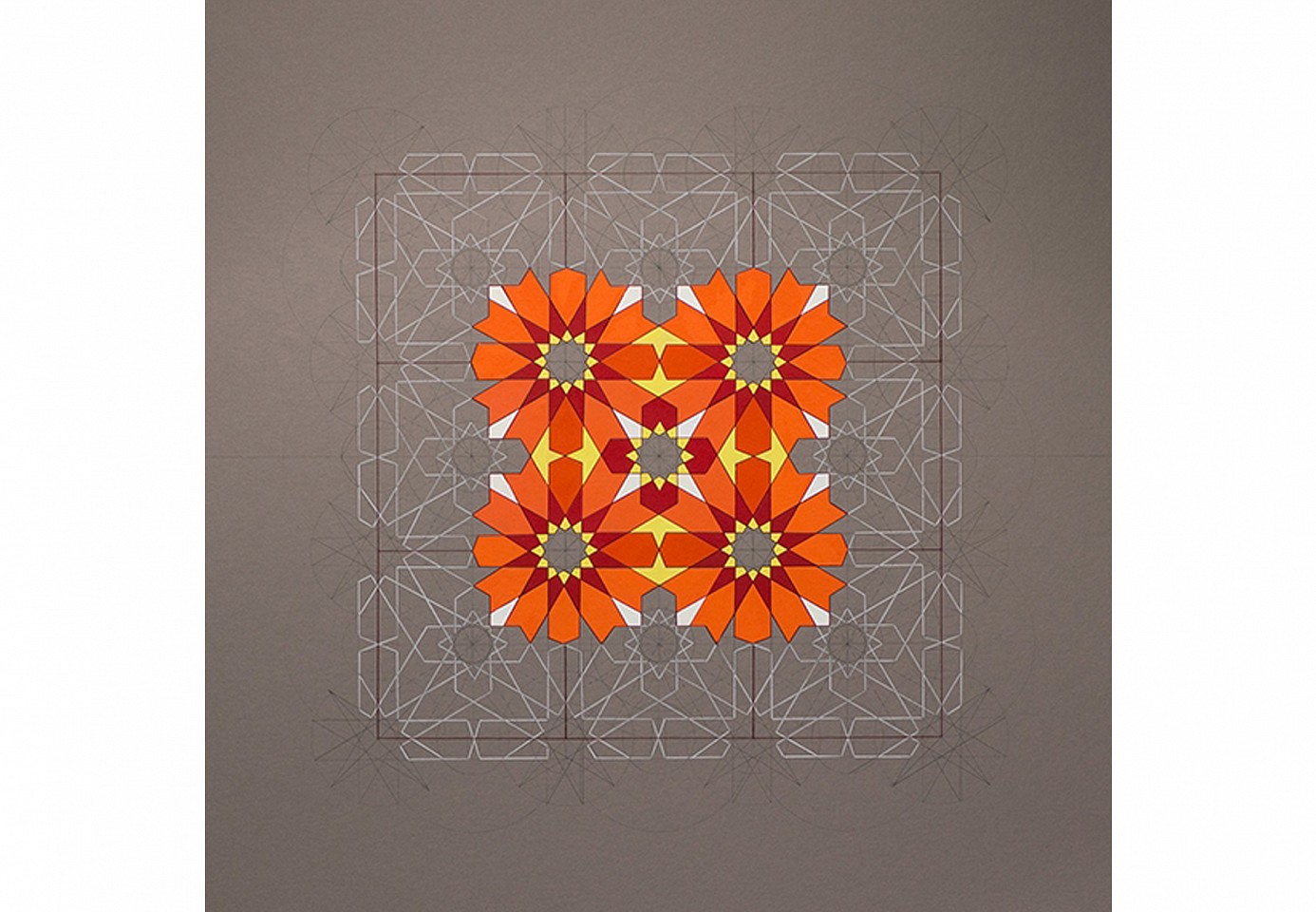

Dodecahedron (Heaven), 2014

Pencil & national pigments on mount board

81 x 81 cm (31 7/8 x 31 7/8 in.)

From the Platonic Solids series

DAN0039

Dana Awartani

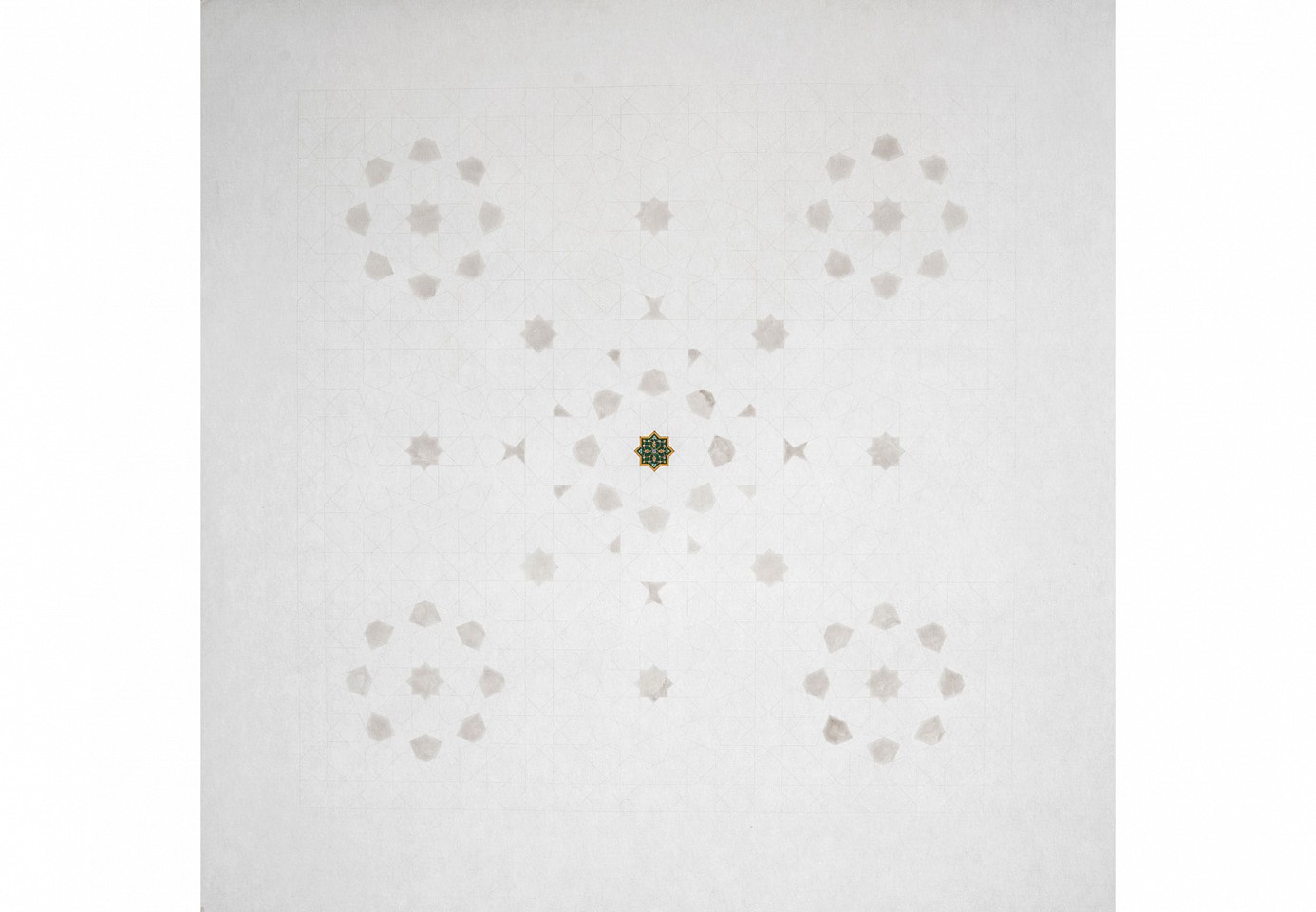

Octahedron (Air), 2014

Pencil & national pigments on mount board

81 x 81 cm (31 7/8 x 31 7/8 in.)

From the Platonic Solids series

DAN0041

Dana Awartani

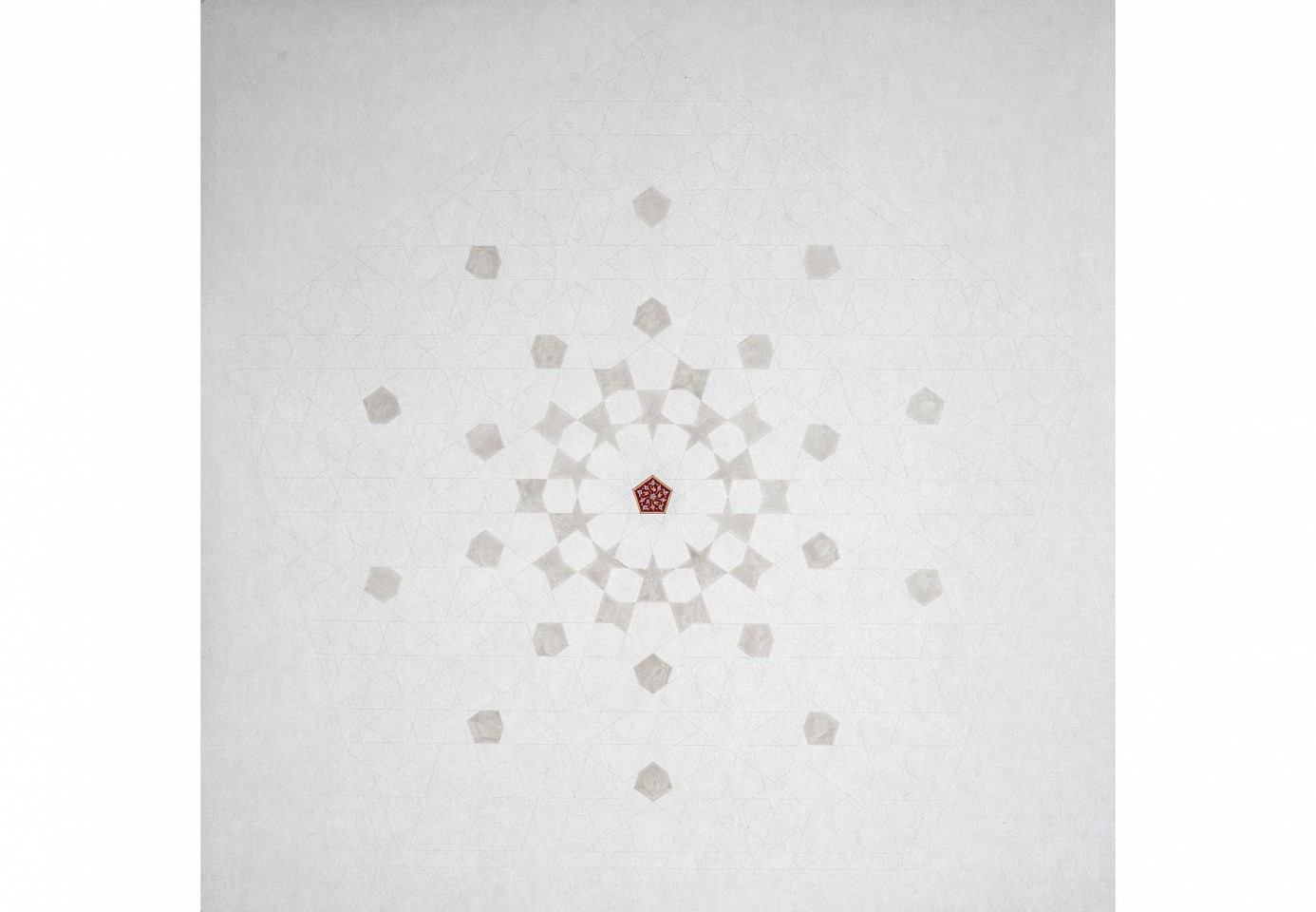

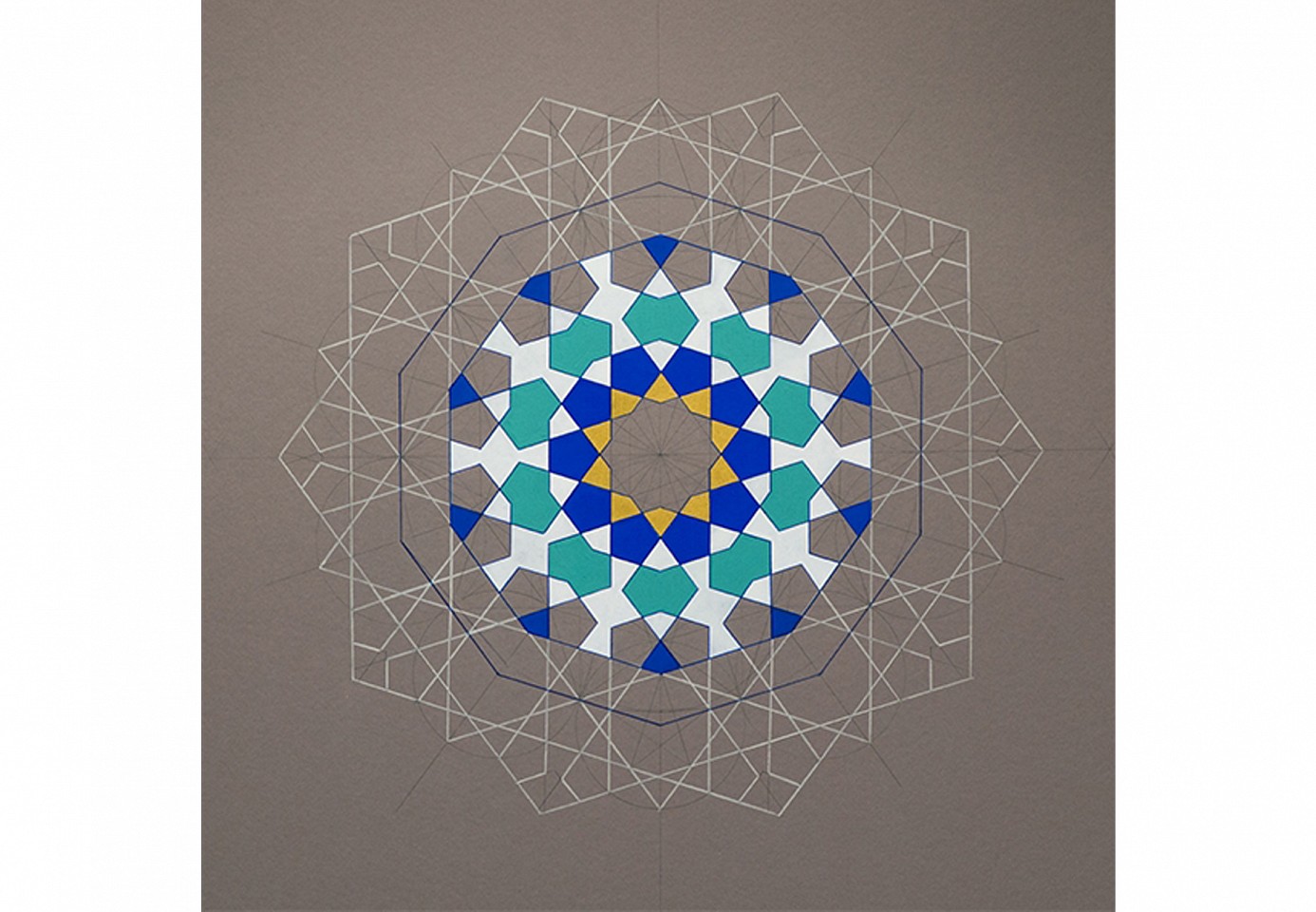

Icosahedron (Water), 2014

Pencil & national pigments on mount board

81 x 81 cm (31 7/8 x 31 7/8 in.)

From the Platonic Solids series

DAN0042

Dana Awartani

Hexahedron (Earth), 2014

Pencil & national pigments on mount board

81 x 81 cm (31 7/8 x 31 7/8 in.)

From the Platonic Solids series

DAN0043

Dana Awartani

Orientalism, 2010

PVC taped room

250 x 200 x 230 cm (98 3/8 x 78 11/16 x 90 1/2 in.)

DAN0044

Dana Awartani

Dhikr, 2014

Ink, gouache and 24 carat gold on paper

150 x 180 cm (59 x 70 13/16 in.)

From the Platonic Solids series

DAN0052

Dana Awartani

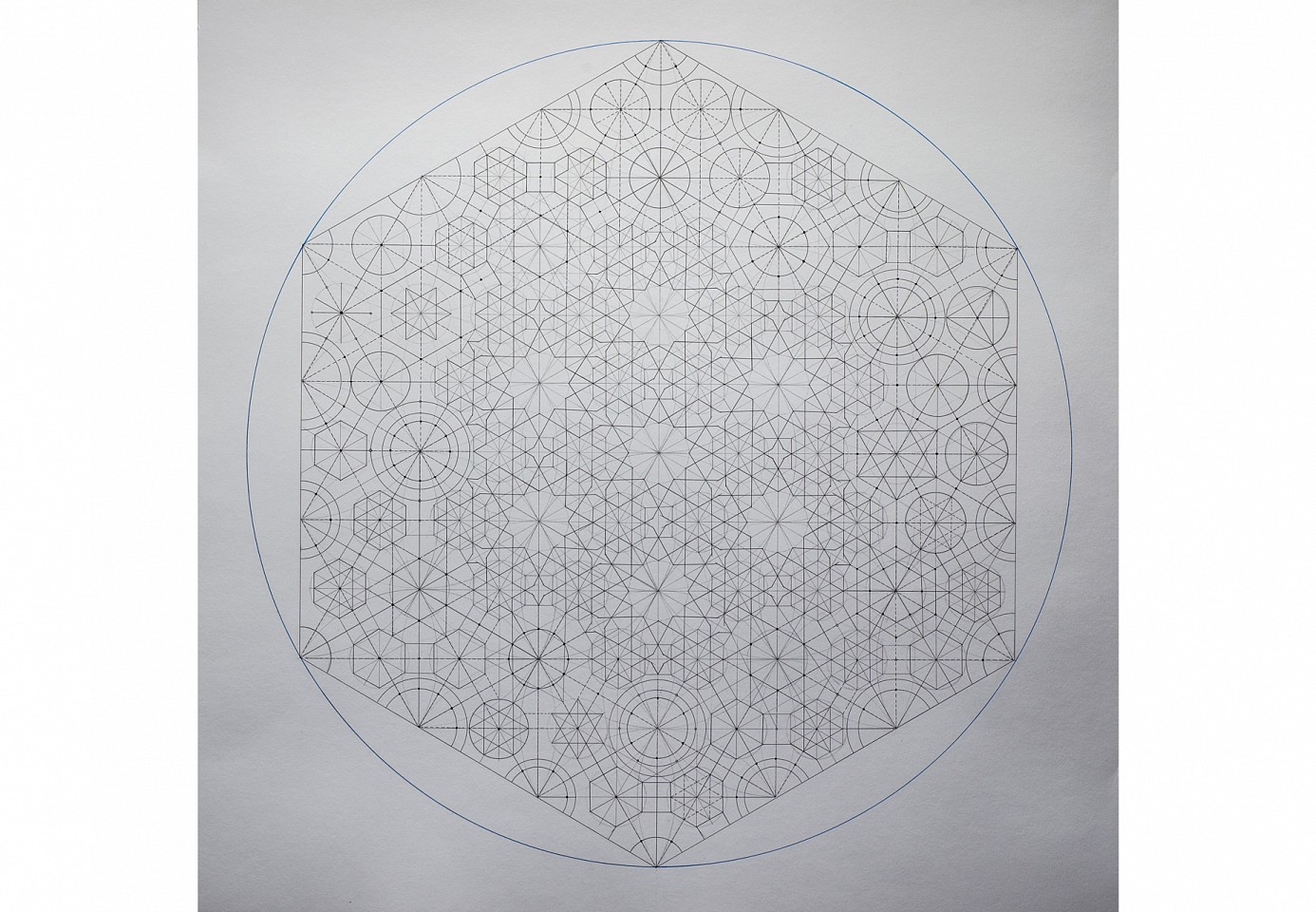

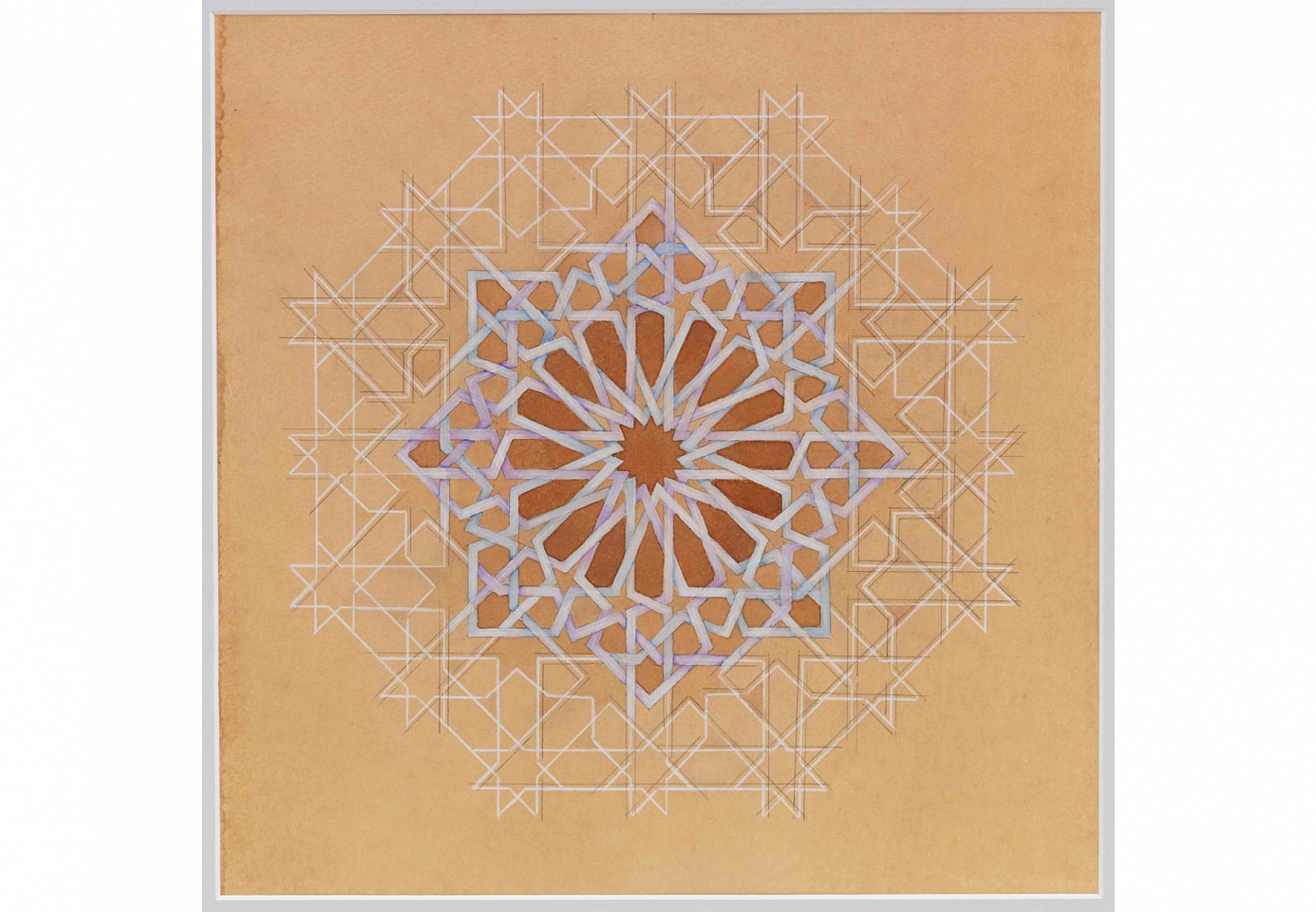

Within A Sphere 4, 2014

Pen and Pencil on paper

58 x 58 cm (22 13/16 x 22 13/16 in.)

From the Platonic Solids series

DAN0054

Dana Awartani

Within A Sphere 6, 2014

Pen and Pencil on paper

58 x 58 cm (22 13/16 x 22 13/16 in.)

From the Platonic Solids series

DAN0053

Dana Awartani

Scroll of The Prophets from the Abjad series, 2015

Gouache and ink on paper

42 x 681 cm (16 1/2 x 268 1/16 in.)

DAN0075

Dana Awartani

Mars from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

59 x 59 cm (23 3/16 x 23 3/16 in.)

DAN0078

Dana Awartani

Sun from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

59 x 59 cm (23 3/16 x 23 3/16 in.)

DAN0079

Dana Awartani

Mercury from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

59 x 59 cm (23 3/16 x 23 3/16 in.)

DAN0081

Dana Awartani

Moon from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015

Shell gold, natural pigment and ink on paper

59 x 59 cm (23 3/16 x 23 3/16 in.)

DAN0082

Dana Awartani

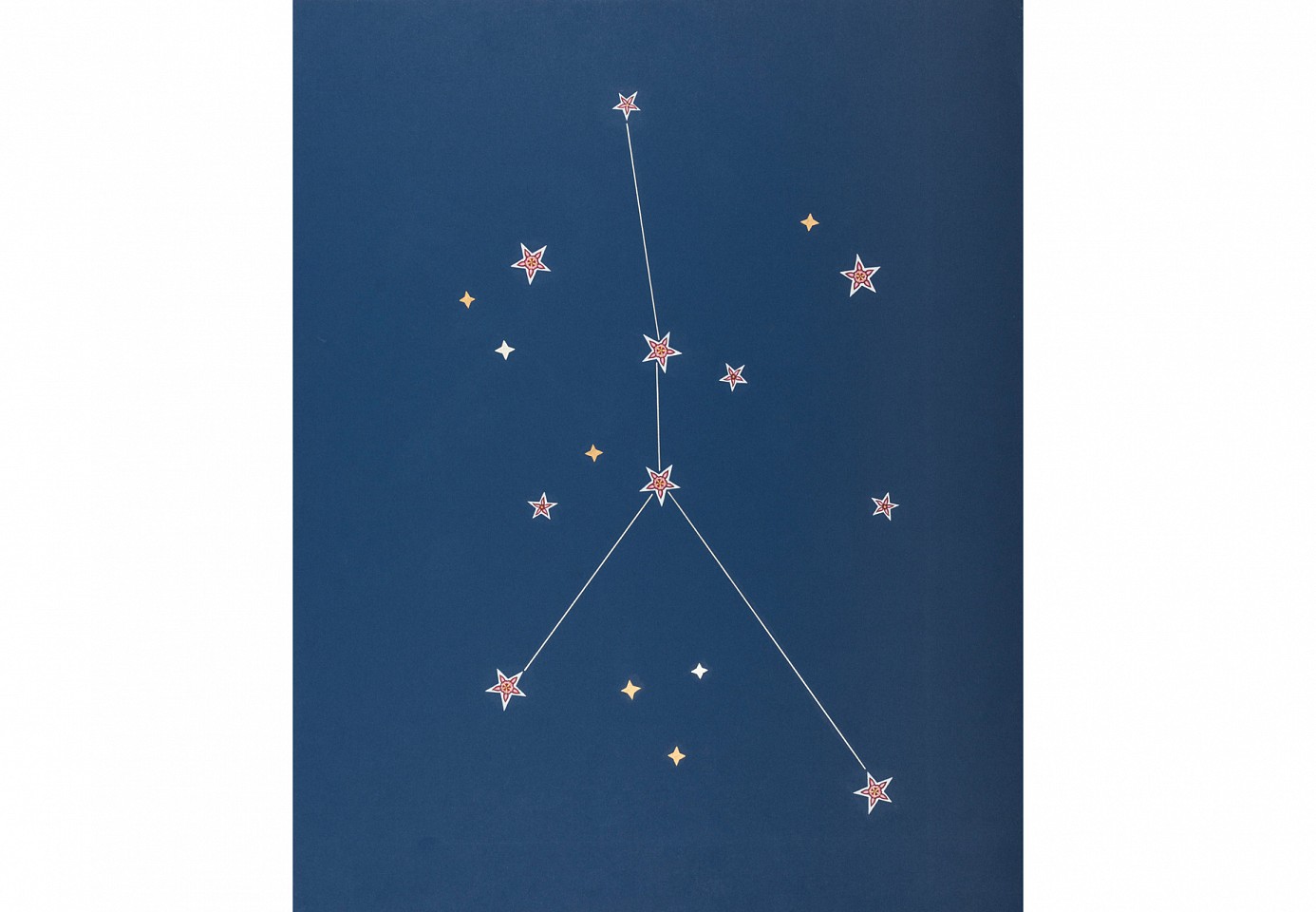

Aries, 2015

Shell gold and gouache on paper

40.5 x 40.5 cm (15 15/16 x 15 15/16 in.)

DAN0088

Dana Awartani

Taurus, 2015

Shell gold and gouache on paper

40.5 x 40.5 cm (15 15/16 x 15 15/16 in.)

DAN0089

Dana Awartani

Gemini, 2015

Shell gold and gouache on paper

40.5 x 40.5 cm (15 15/16 x 15 15/16 in.)

DAN0090

Dana Awartani

Cancer, 2015

Shell gold and gouache on paper

40.5 x 40.5 cm (15 15/16 x 15 15/16 in.)

DAN0091

Dana Awartani

Al Ikhlas (Unity), 2013

Gouache and 24 carot gold on prepared paper

40 x 40 cm (15 3/4 x 15 3/4 in.)

DAN0008

Dana Awartani

Al Falaq (Daybreak), 2013

Gouache and 24 carot gold on prepared paper

40 x 40 cm (15 3/4 x 15 3/4 in.)

DAN0009

Dana Awartani

Al Nas (Mankind), 2013

Gouache and 24 carot gold on prepared paper

40 x 40 cm (15 3/4 x 15 3/4 in.)

DAN0007

Dana Awartani

Abdulraheem (Slave of The Merciful), 2012

Pencil on mount board

100 x 100 cm (39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in.)

DAN0001

Dana Awartani

Abdulrahman (Slave of The Compassionate), 2012

Pencil on mount board

100 x 100 cm (39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in.)

DAN0000

Dana Awartani

Geometric Progression Piece #1, 2012

Pencil and pen on mount board

100 x 100 cm (39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in.)

DAN0002

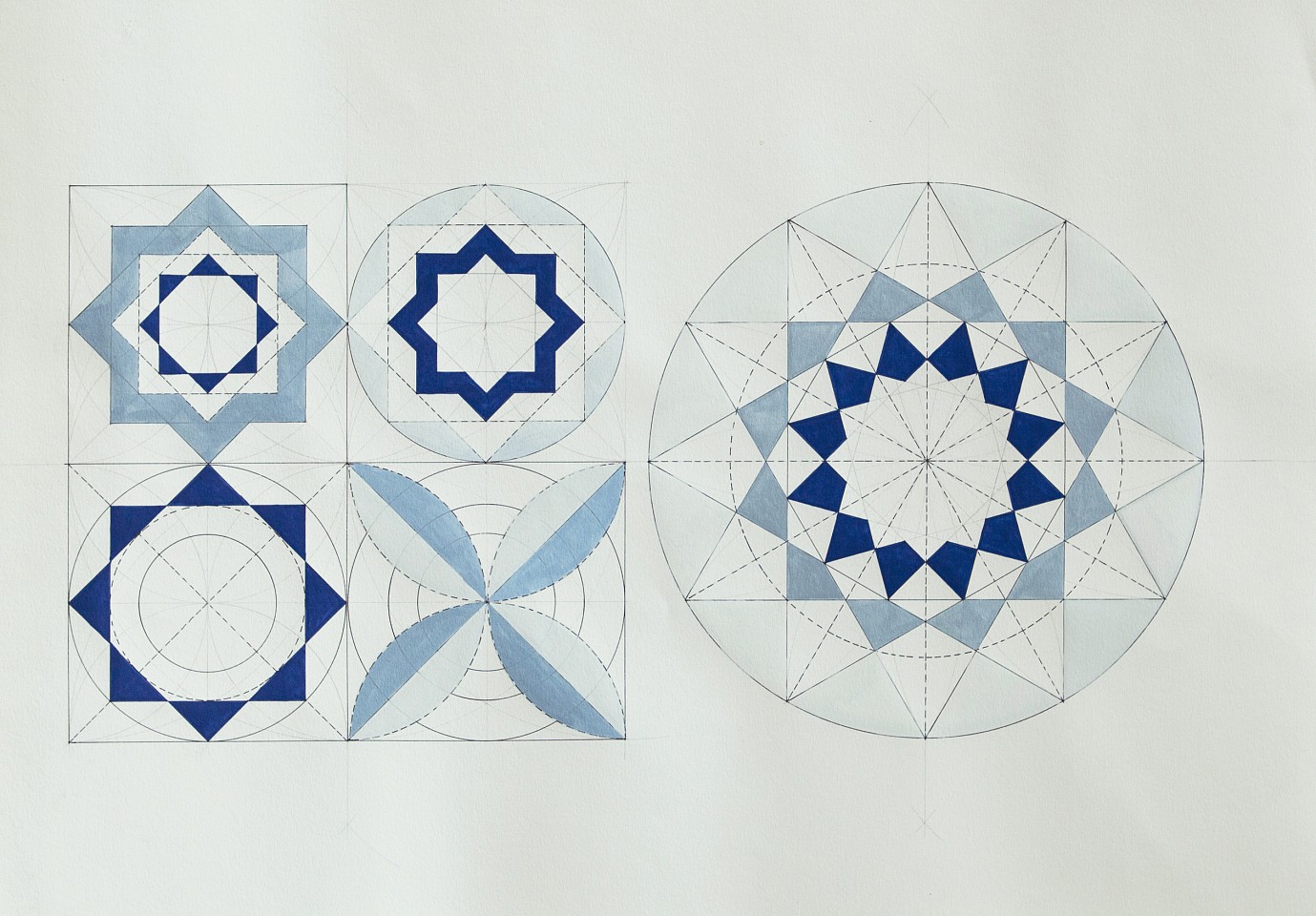

Dana Awartani

Geometric Progression Piece #2, 2012

Pencil and pen on mount board

100 x 100 cm (39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in.)

DAN0003

Dana Awartani

Progressional Drawing #3, 2012

Pen, Gouache and shell gold on mount board

42 x 87.5 cm (16 1/2 x 34 1/2 in.)

DAN0010

Dana Awartani

Progressional Drawing #4, 2012

Pen, Gouache and shell gold on mount board

42 x 87.5 cm (16 1/2 x 34 1/2 in.)

DAN0011

Dana Awartani

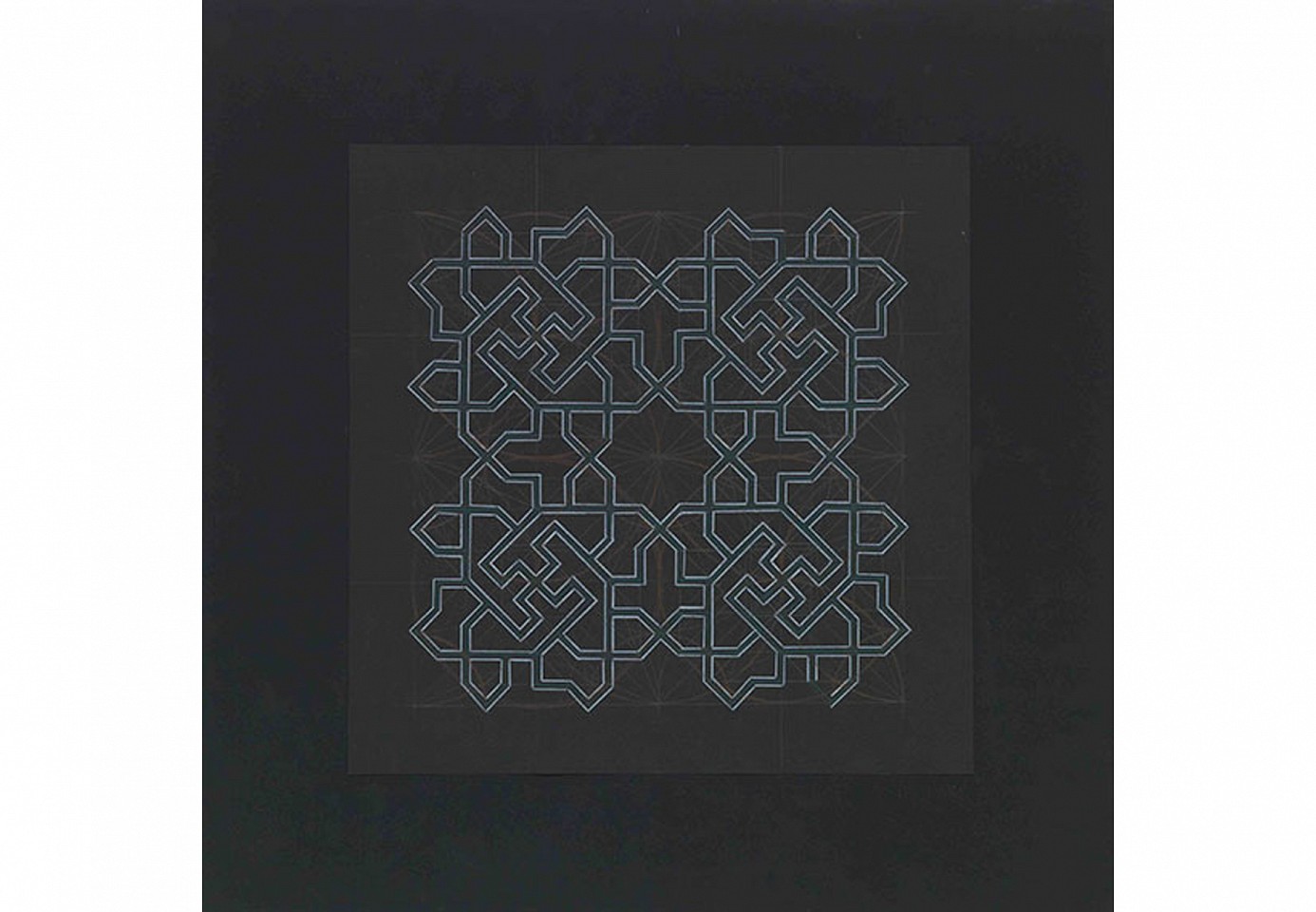

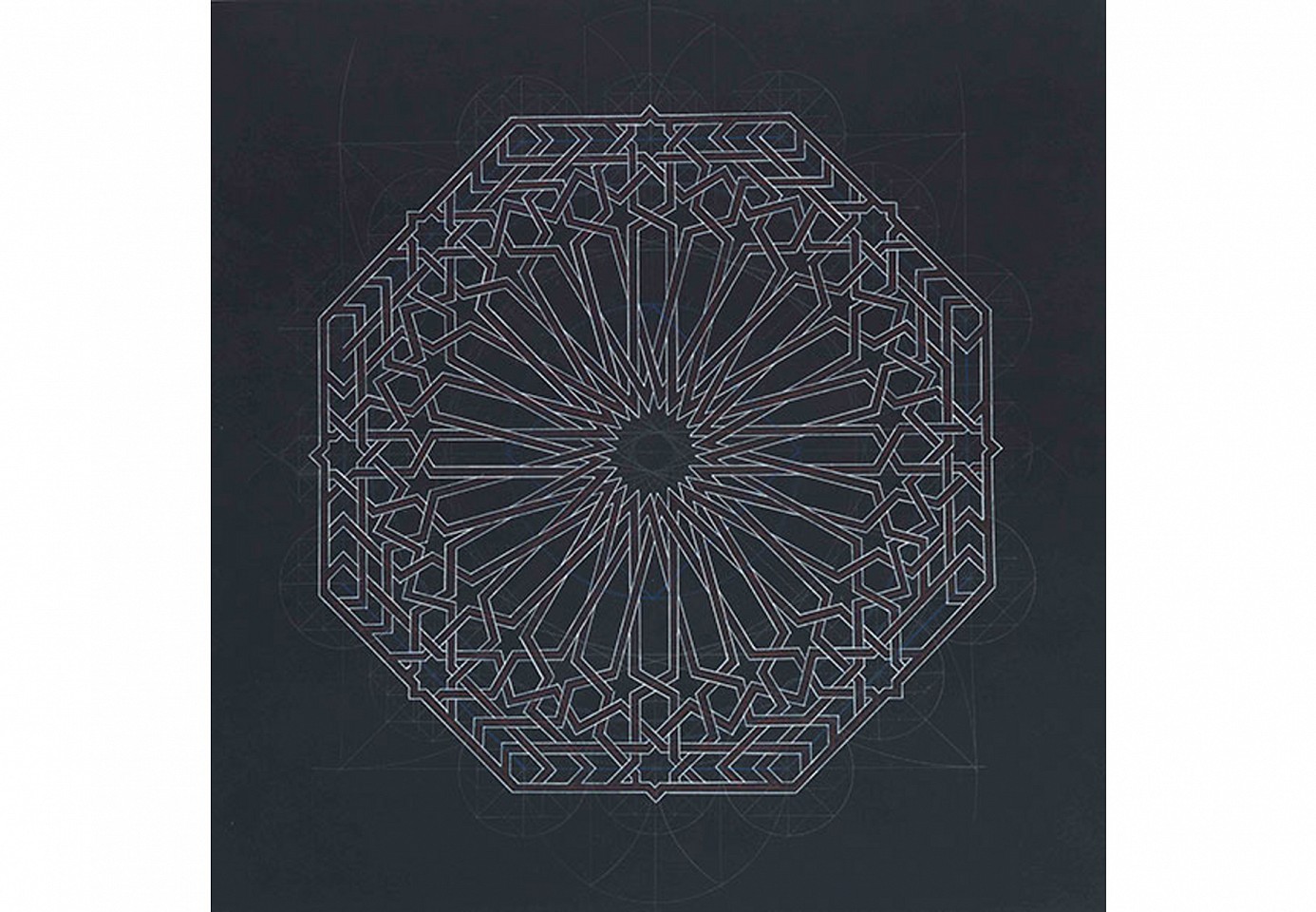

Symetry, 2011

Pencil on black paper

27 x 27 cm (10 5/8 x 10 5/8 in.)

DAN0005

Dana Awartani

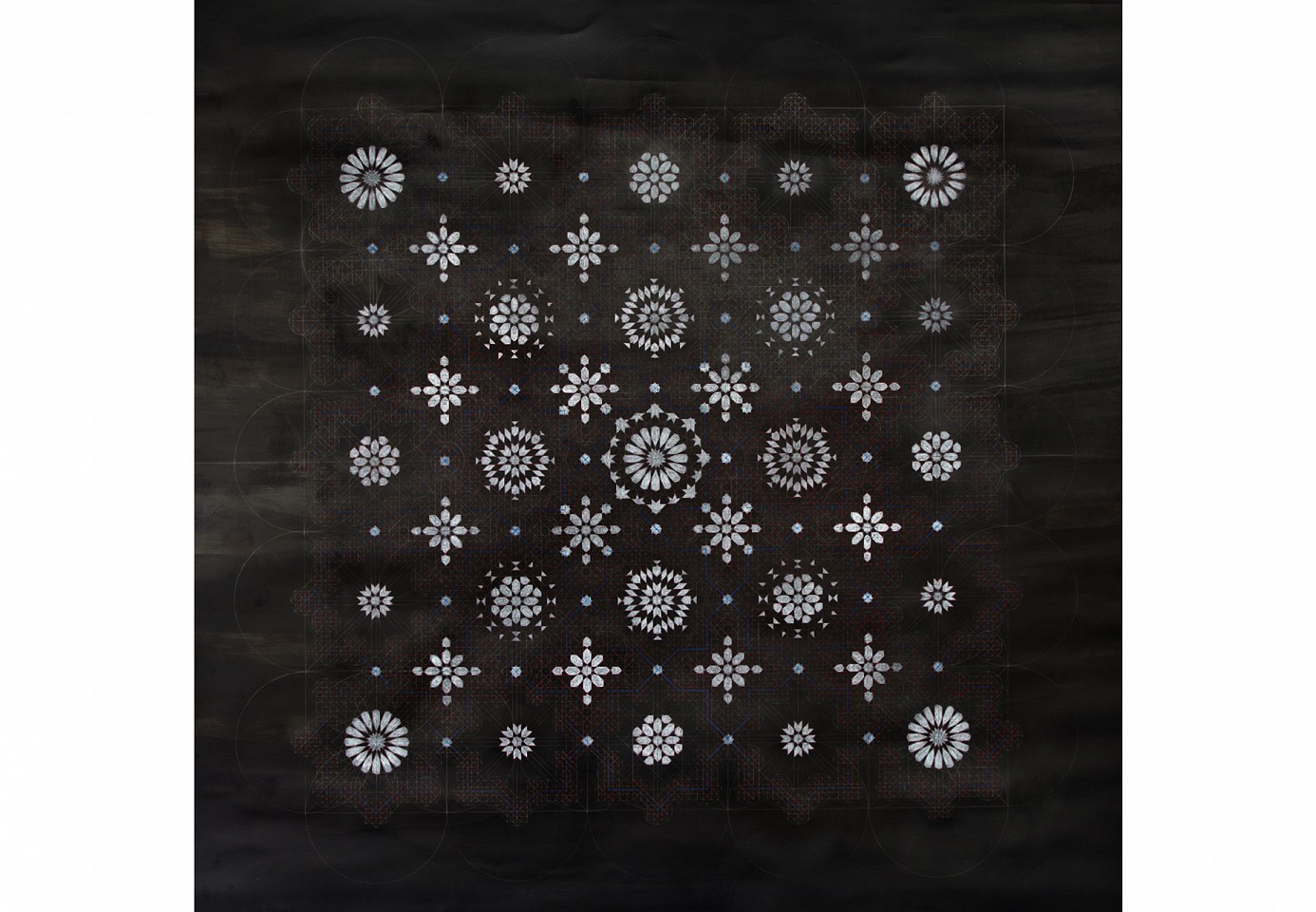

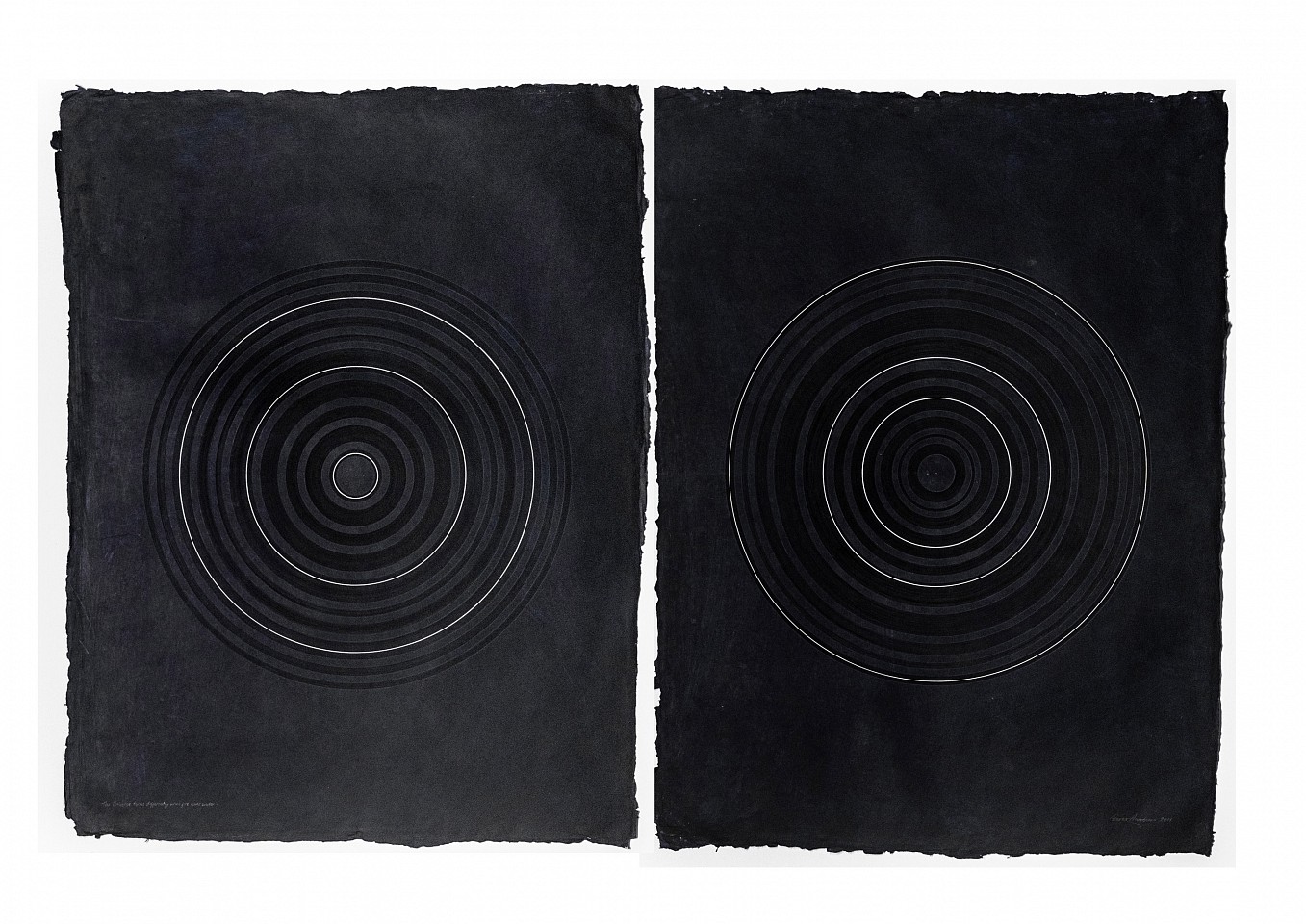

The Breath of the compassionate, 2013

Pencil on black paper

150 x 150 cm (59 x 59 in.)

DAN0004

Dana Awartani

Gamar (The Moon), 2011

Pencil on black paper

48.5 x 48.5 cm (19 1/8 x 19 1/8 in.)

DAN0006

Dana Awartani

Al Malaika (The Angels), 2013

Shell gold and natural pigments on prepared paper

23 x 25.5 cm (9 x 10 in.)

DAN0013

Dana Awartani

Al Sahra (The Desert), 2013

Natural pigments on prepared paper

26 x 26 cm (10 1/4 x 10 1/4 in.)

DAN0014

Dana Awartani

Lotus Flower I, 2012

Shell gold and natural pigments on prepared paper

16.5 x 16.5 cm (6 1/2 x 6 1/2 in.)

DAN0020

Dana Awartani

Lotus Flower III, 2012

Shell gold and natural pigments on prepared paper

16.5 x 16.5 cm (6 1/2 x 6 1/2 in.)

DAN0022

Dana Awartani

Al Munir (The Enlighter), 2011

Gouache on Paper

30 x 30 cm (11 3/4 x 11 3/4 in.)

DAN0025

Dana Awartani

Thaminya (Eight), 2011

Parquetry and glass box

18 x 18 cm (7 1/8 x 7 1/8 in.)

DAN0034

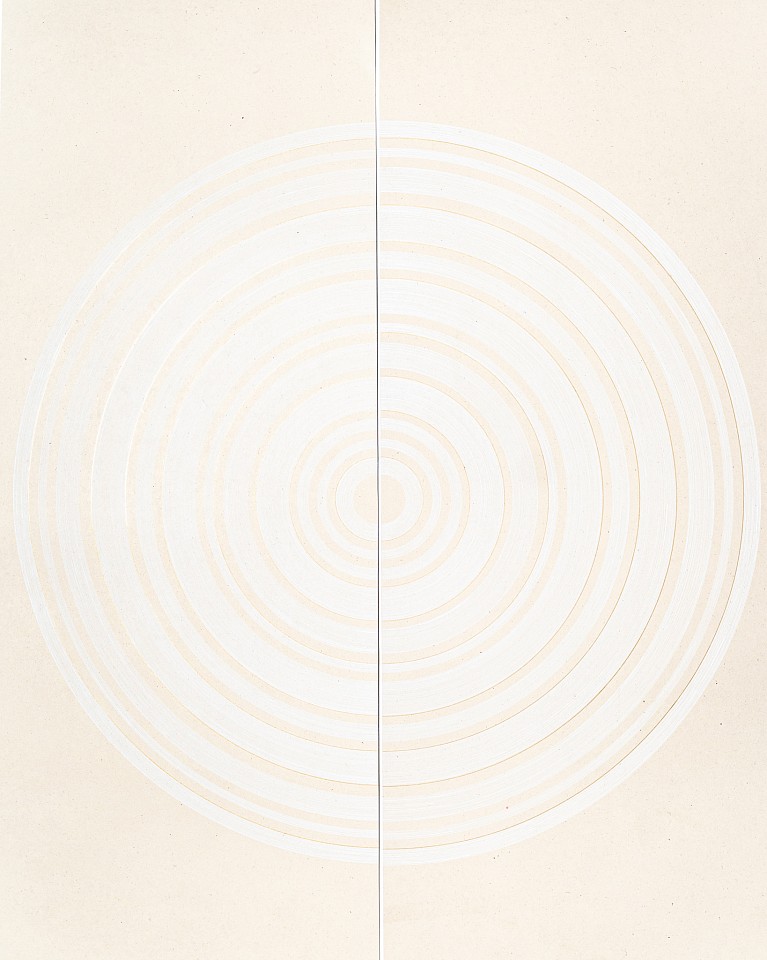

Dana Awartani

Untitled, 2021

Gouache on handmade paper

DAN0253

Dana Awartani

In Search of Silence, 2019

Gouache on hand made paper

DAN0229

Dana Awartani

The Union of Fire and Water I, 2019

Gouache and shell gold on hand made paper

DAN0227

Dana Awartani

The Union of Fire and Water II, 2019

Gouache and shell gold on hand made paper

DAN0228

Dana Awartani

When Fire Loves Water, 2019

Gouache and shell gold on hand made paper

DAN0224

Dana Awartani

You are the Universe in ecstatic motion I, 2019

Gouache and shell gold on hand made paper

DAN0225

Dana Awartani

You are the Universe in ecstatic motion II, 2019

Gouache and shell gold on hand made paper

DAN0226

Dana Awartani

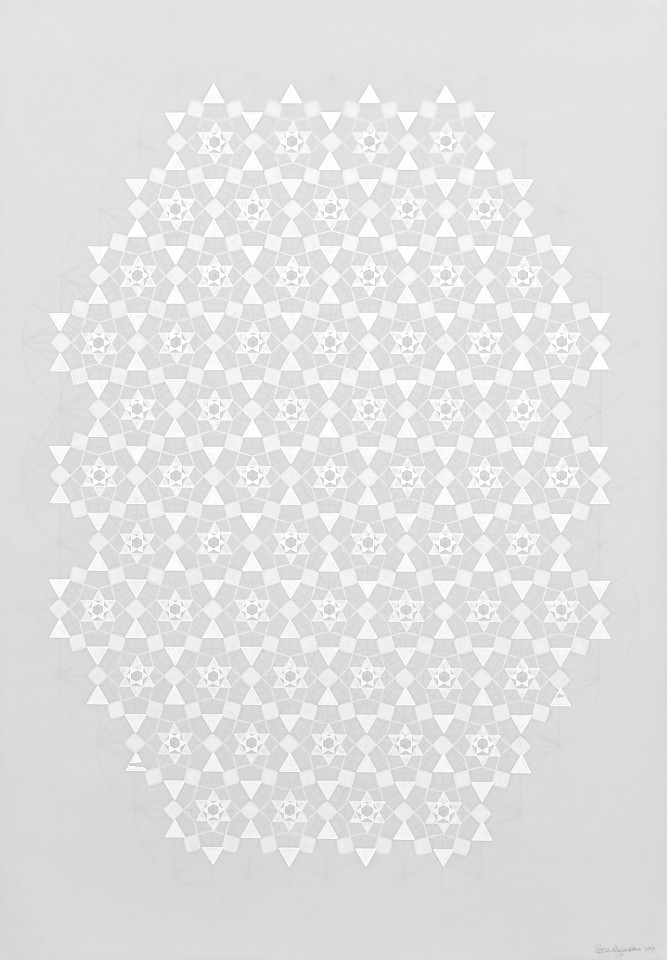

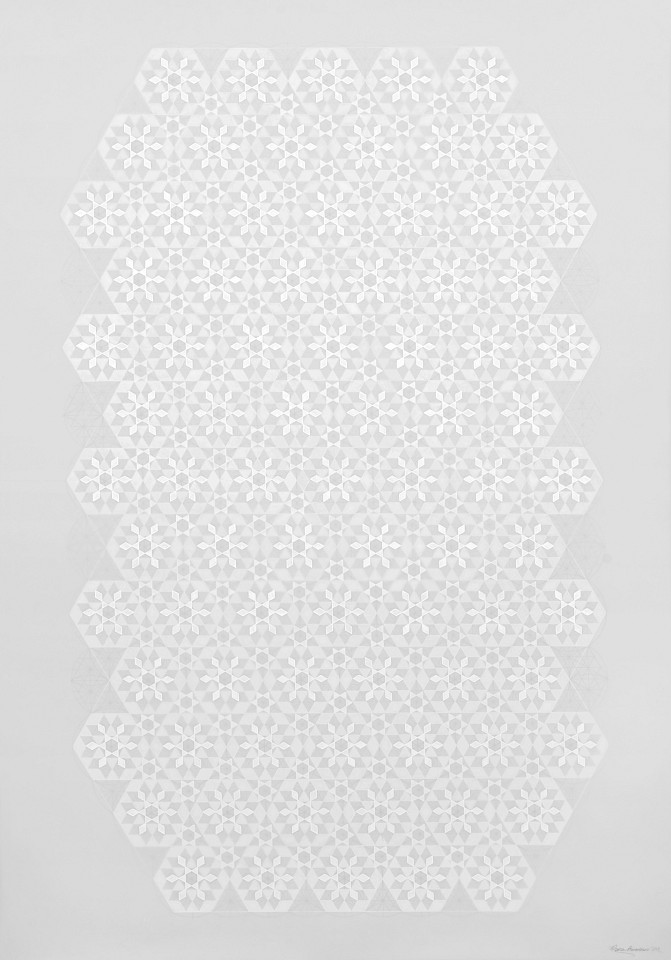

Jali 12, 2018

White gouach on translucent drafting film (3 layers)

DAN0157

Dana Awartani

Jali 3, 2018

White gouach on translucent drafting film (3 layers)

DAN0148

Dana Awartani

Listen to My Words, 2018

Multi media (7 panels of hand embroidery on silk and sound installation)

DAN0141

Dana Awartani

Untitled, 2018

Shell gold and gouache on paper

DAN0144

Dana Awartani

Alif from the Abjad Hawaz, 2017

Shell gold, gouahe, and ink on paper

DAN0130

Dana Awartani

Ba from the Abjad Hawaz, 2017

Shell gold, gouahe, and ink on paper

DAN0131

Dana Awartani

Dal from the Abjad Hawaz, 2017

Shell gold, gouahe, and ink on paper

DAN0133

Dana Awartani

Ha from the Abjad Hawaz, 2017

Shell gold, gouahe, and ink on paper

DAN0134

Dana Awartani

Haa from the Abjad Hawaz, 2017

Shell gold, gouahe, and ink on paper

DAN0137

Dana Awartani

Jeem from the Abjad Hawaz, 2017

Shell gold, gouahe, and ink on paper

DAN0132

Dana Awartani

Untitled, 2017

Guache and shell gold on paper (8 Panels)

DAN0124

Dana Awartani

Waw from the Abjad Hawaz, 2017

Shell gold, gouahe, and ink on paper

DAN0135

Dana Awartani

Za from the Abjad Hawaz, 2017

Shell gold, gouahe, and ink on paper

DAN0136

Dana Awartani

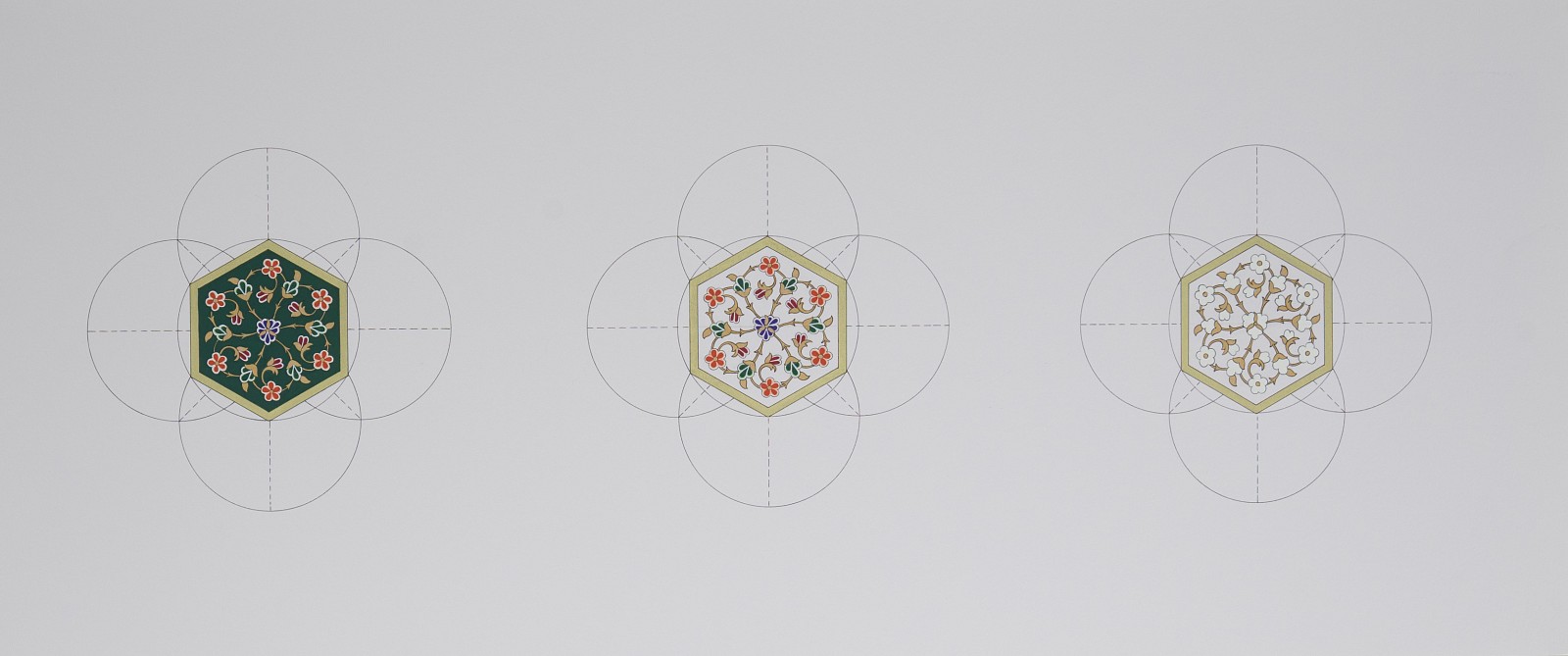

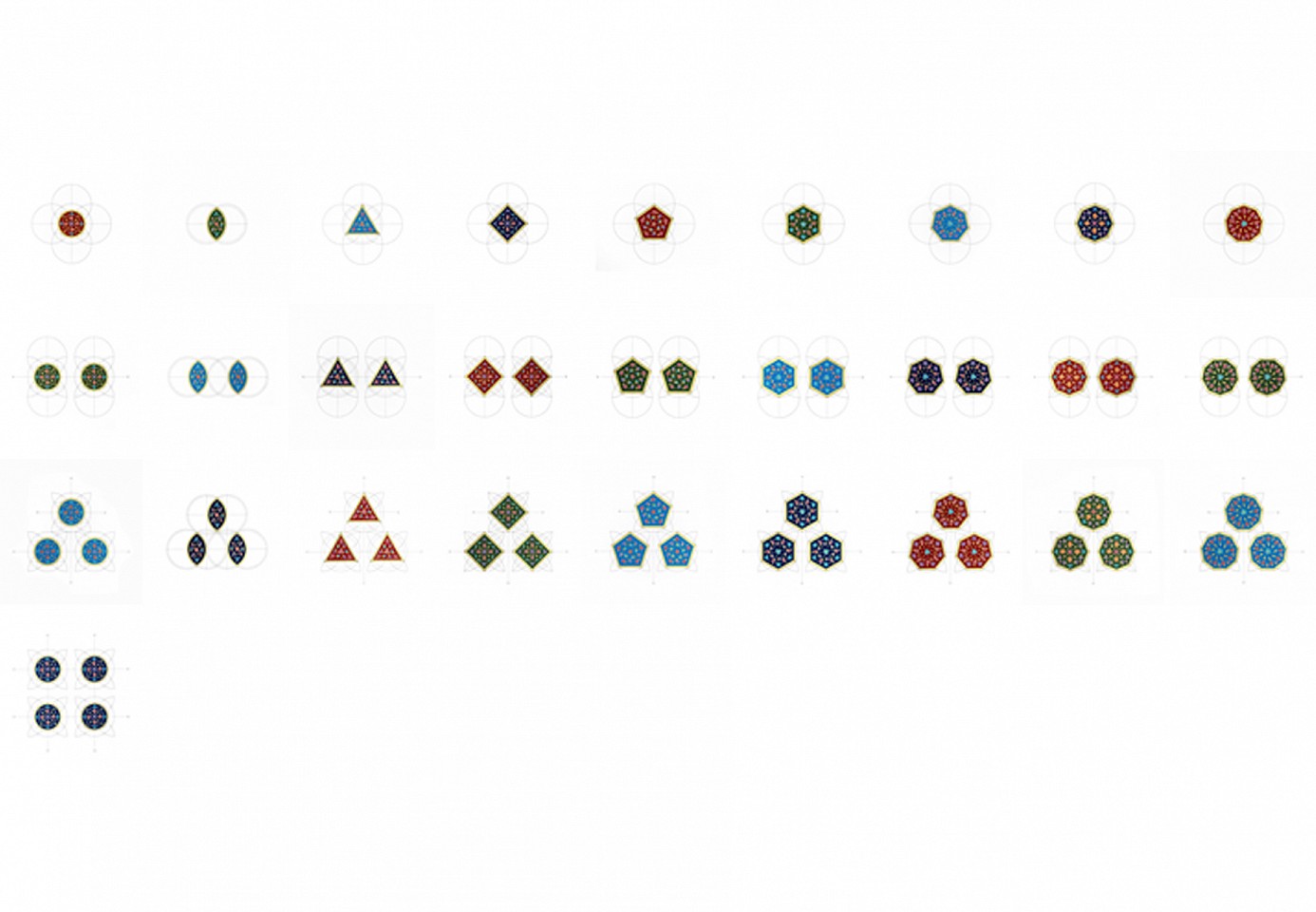

Abjad Hawaz series, 2016

Shell gold, ink and gouache on paper

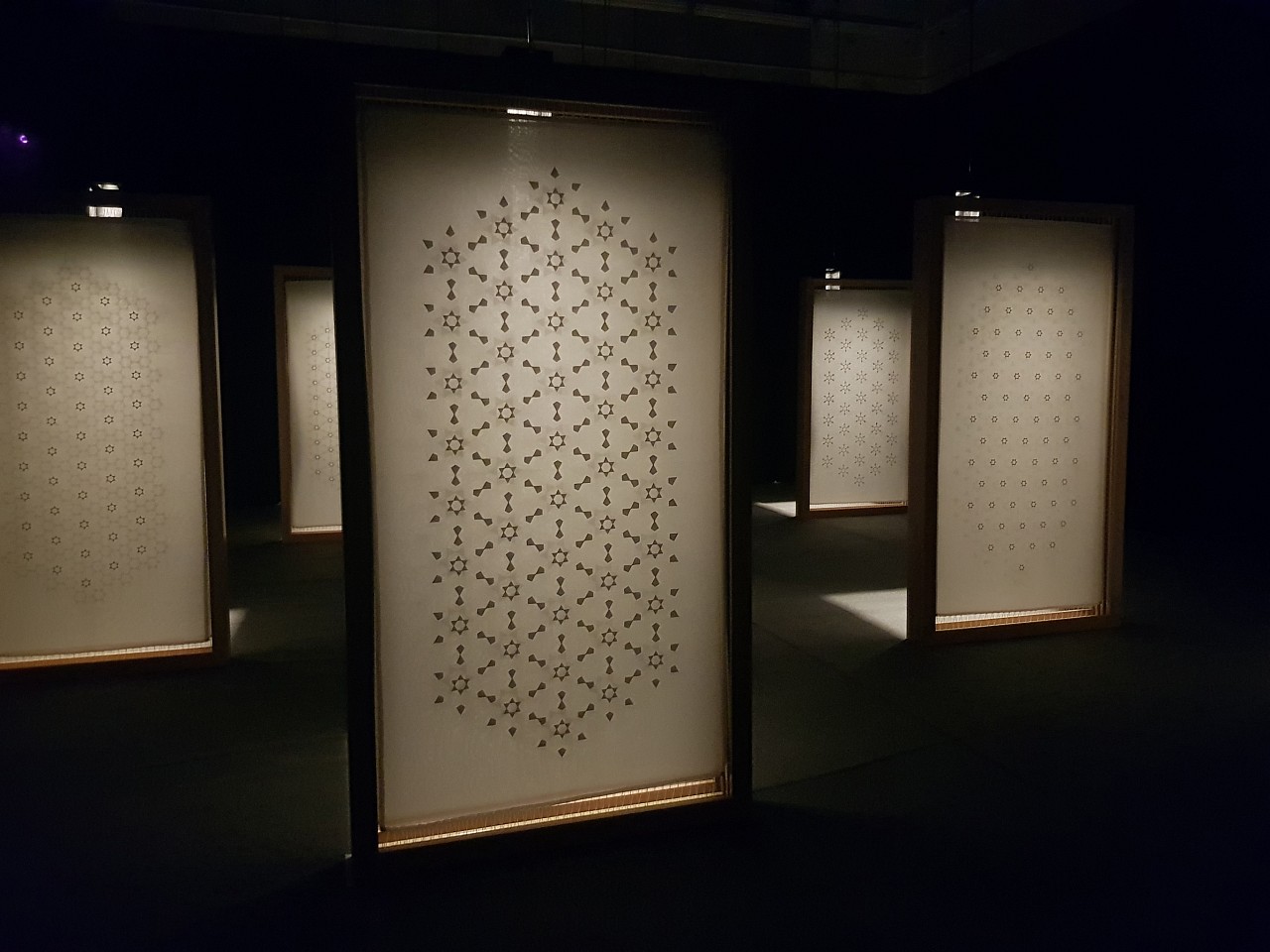

Dana Awartani

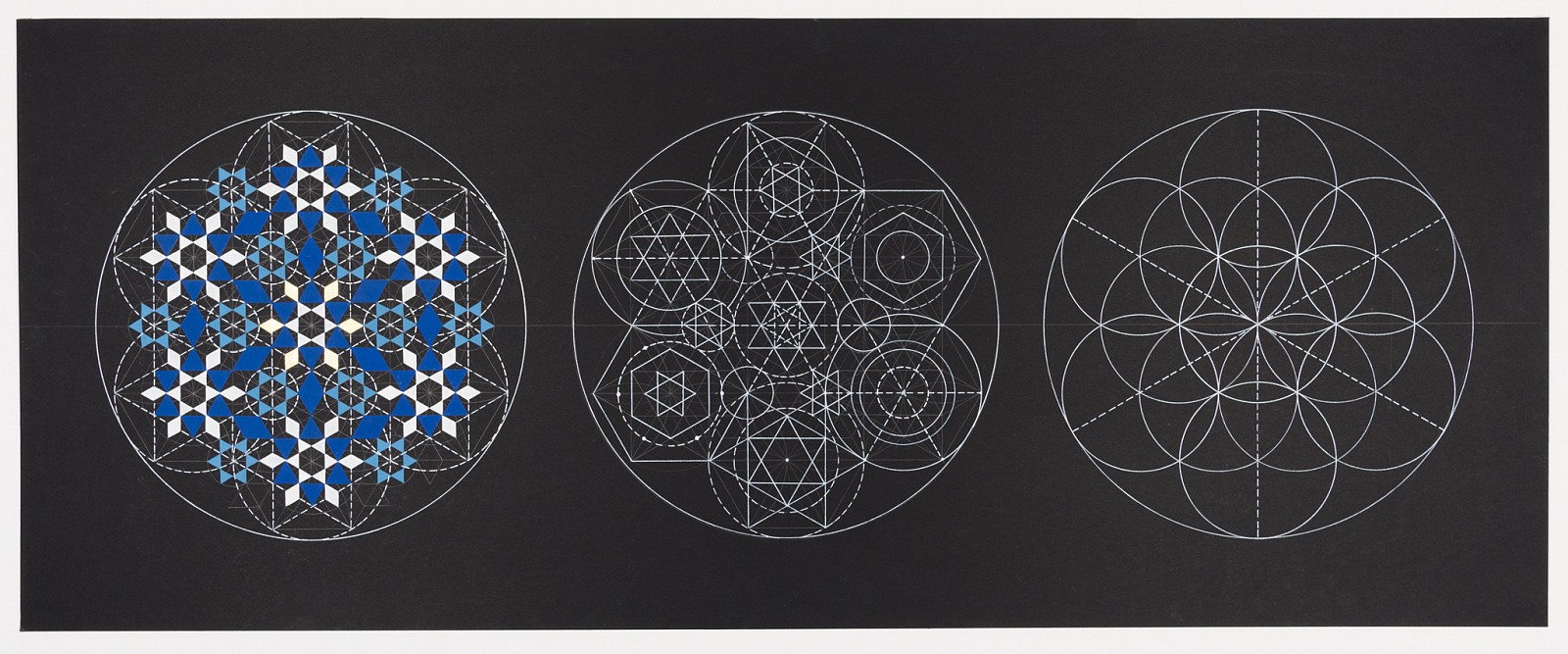

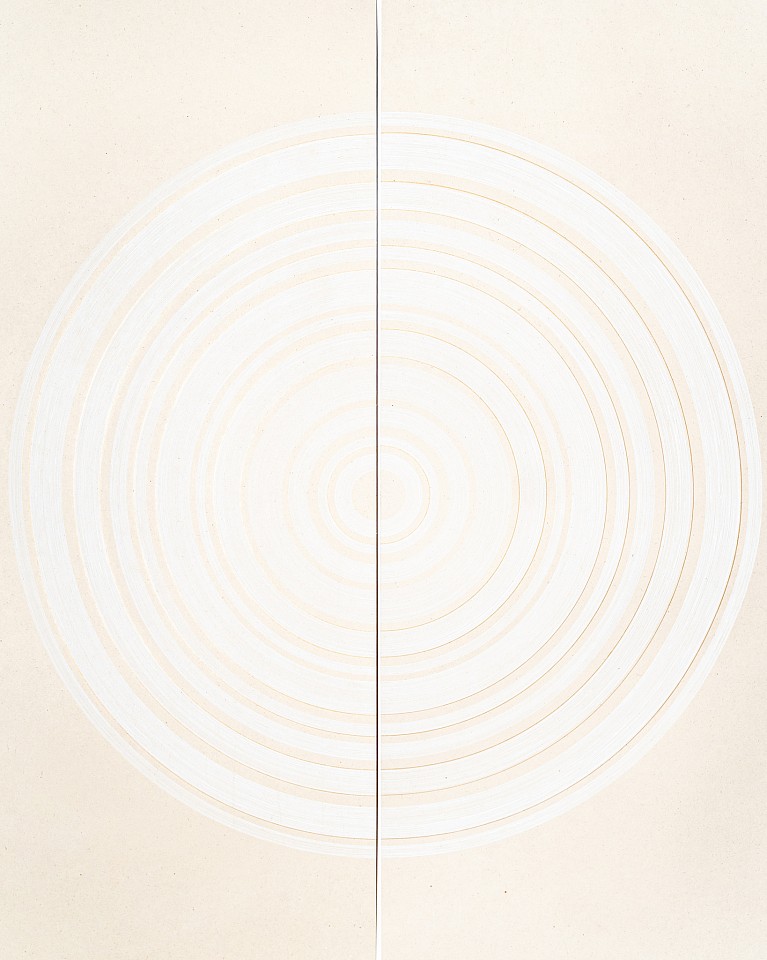

All [heavenly bodies] swim along, each in its orbit, 2016

Mixed Media

150 x 150 cm

Dana Awartani

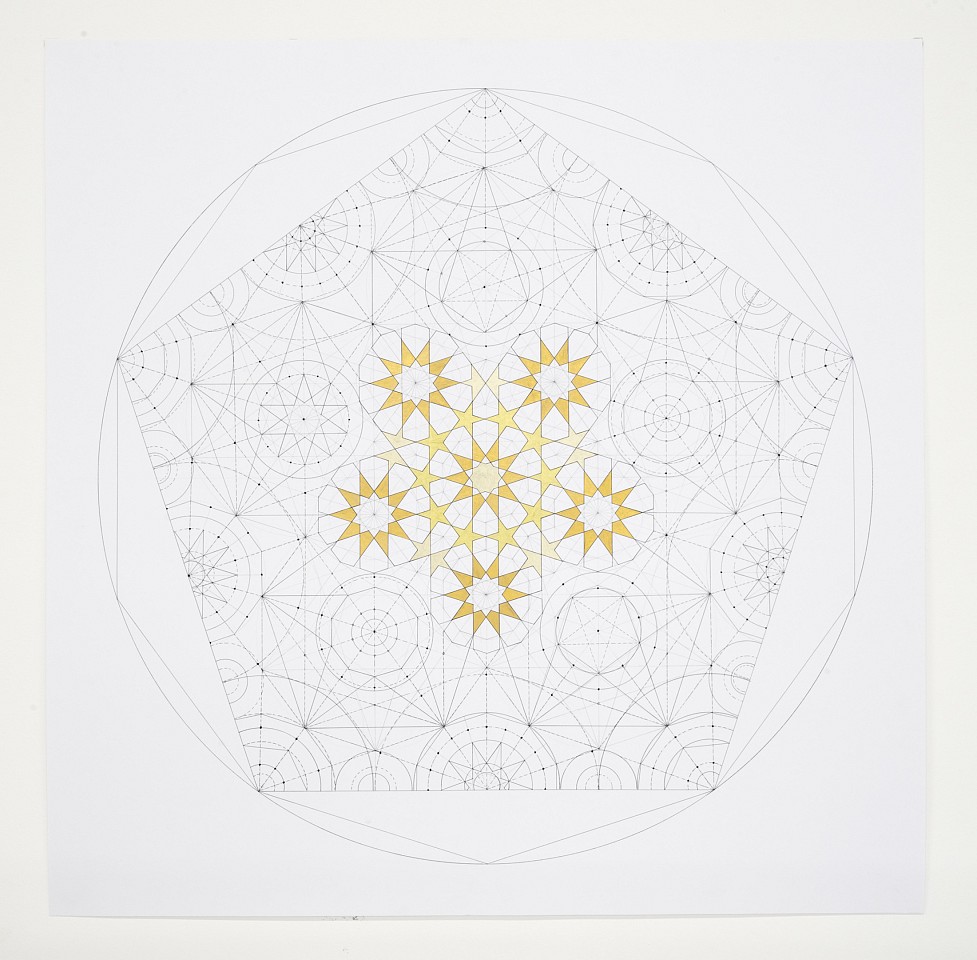

Dodecahedron Within a Icosahedron from The Platonic Solid Duals Series, 2016

Shell gold and gouache on paper

54 x 54 cm

Dana Awartani

Dodecahedron Within a Icosahedron from The Platonic Solid Duals Series, 2016

Shell gold and gouache on paper

54 x 54 cm

Dana Awartani

Love is my Law, Love is my Faith, 2016

Embroidery on Silk

DAN0126

Dana Awartani

Octahedron Within a Cube from The Platonic Solid Duals Series, 2016

Shell gold and ink on paper

DAN0114

Dana Awartani

Progressional Drawing #16, 2016

Gel pen and colored pencil on paper

DAN0177

Dana Awartani

Progressional Drawing #17, 2016

Gel pen and colored pencil on paper

DAN0178

Dana Awartani

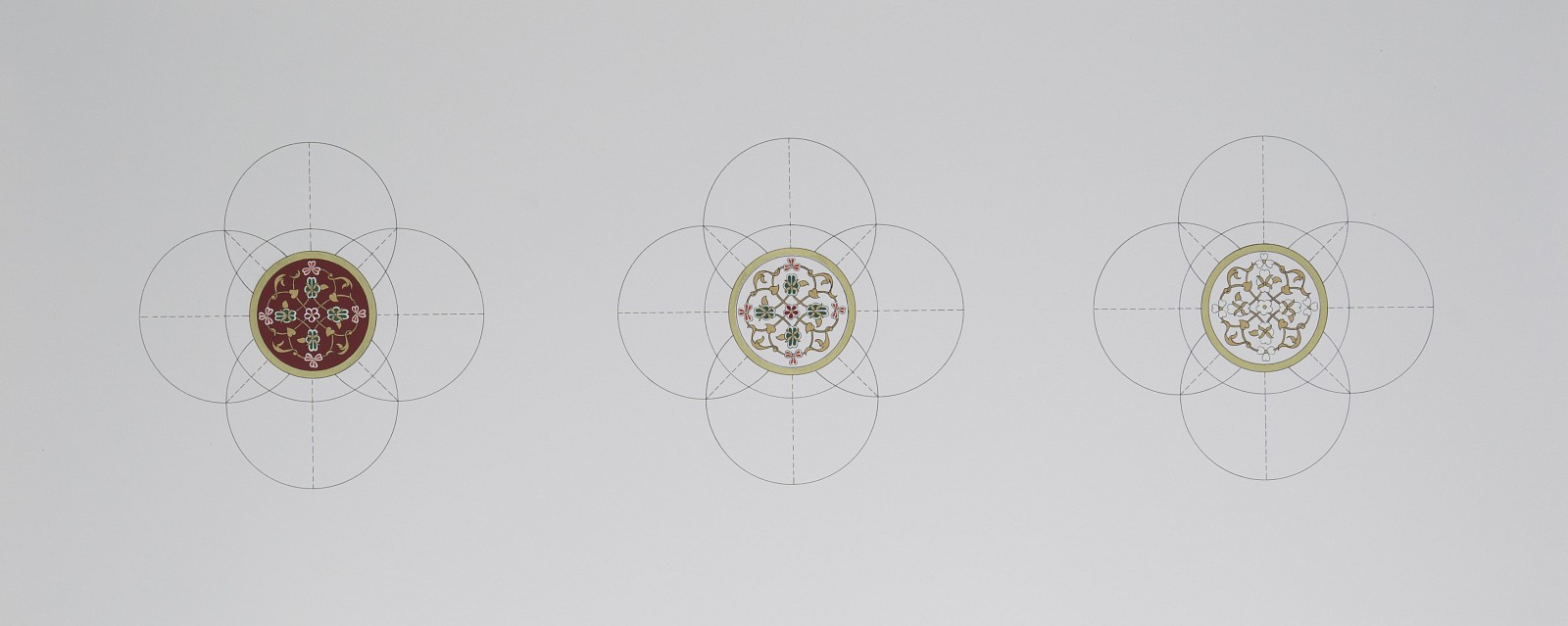

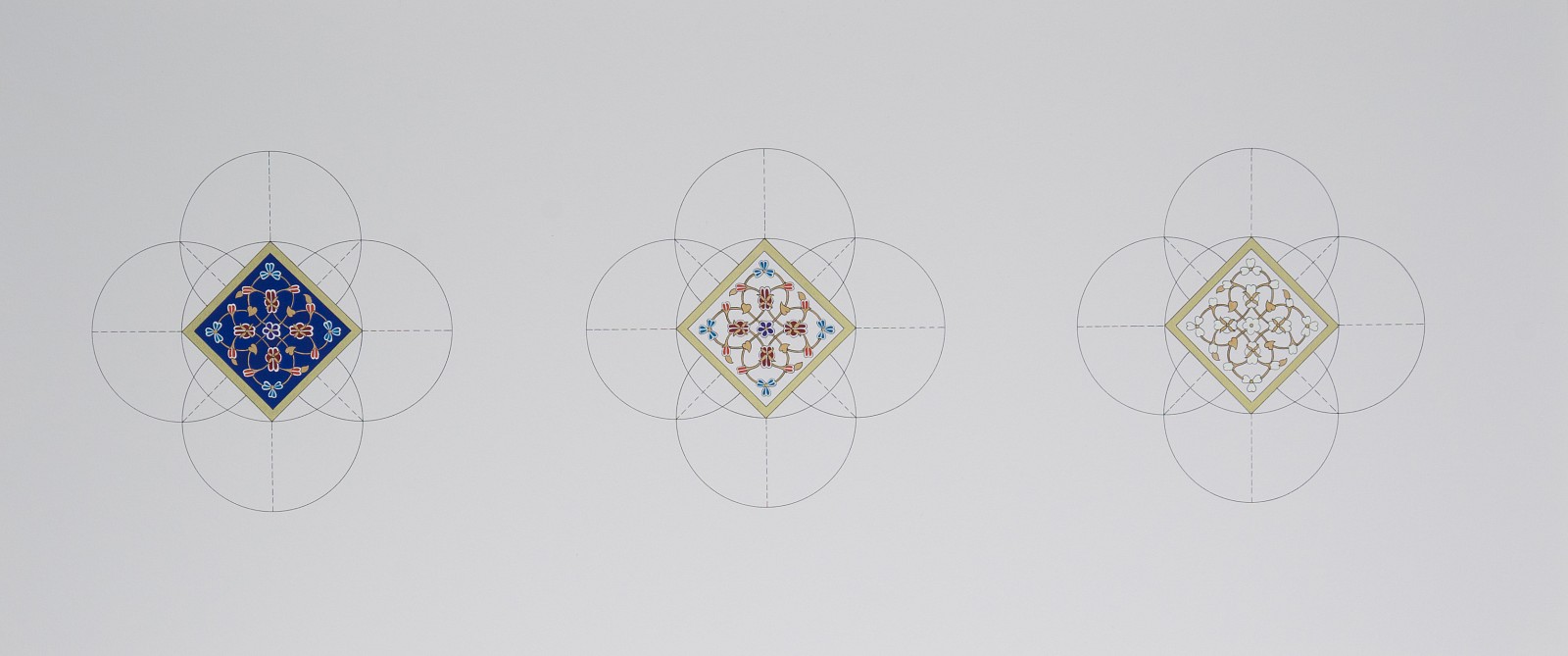

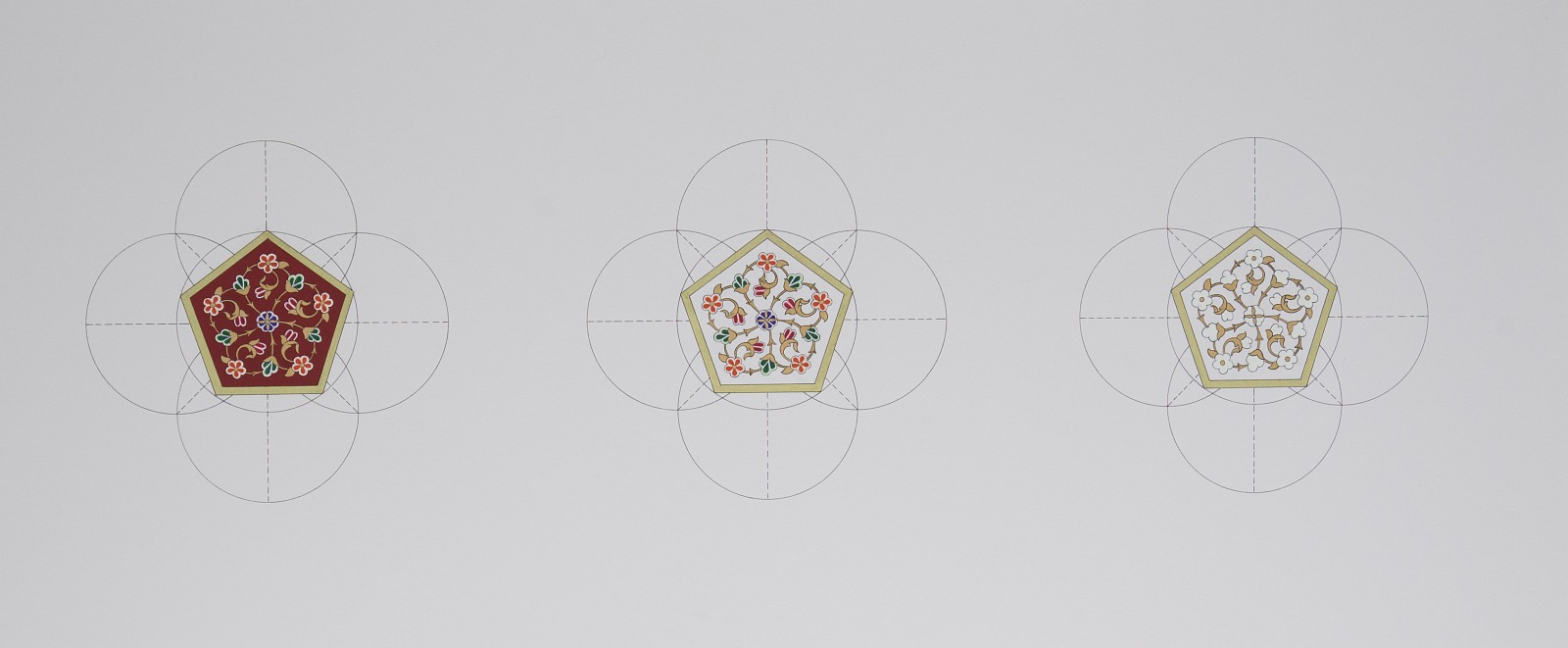

Decoding the prophets

Study Drawing I, 2015

Gouache and ink on paper

DAN0164

Dana Awartani

Decoding the prophets

Study Drawing III, 2015

Gouache and ink on paper

DAN0166

Dana Awartani

Decoding the prophets

Study Drawing IV, 2015

Gouache and ink on paper

DAN0167

Dana Awartani

Decoding the prophets

Study Drawing V, 2015

Gouache and ink on paper

DAN0168

![Dana Awartani, All [heavenly bodies] swim along, each in its orbit

2016, Mixed Media](/images/29138_h125w125gt.5.jpg)

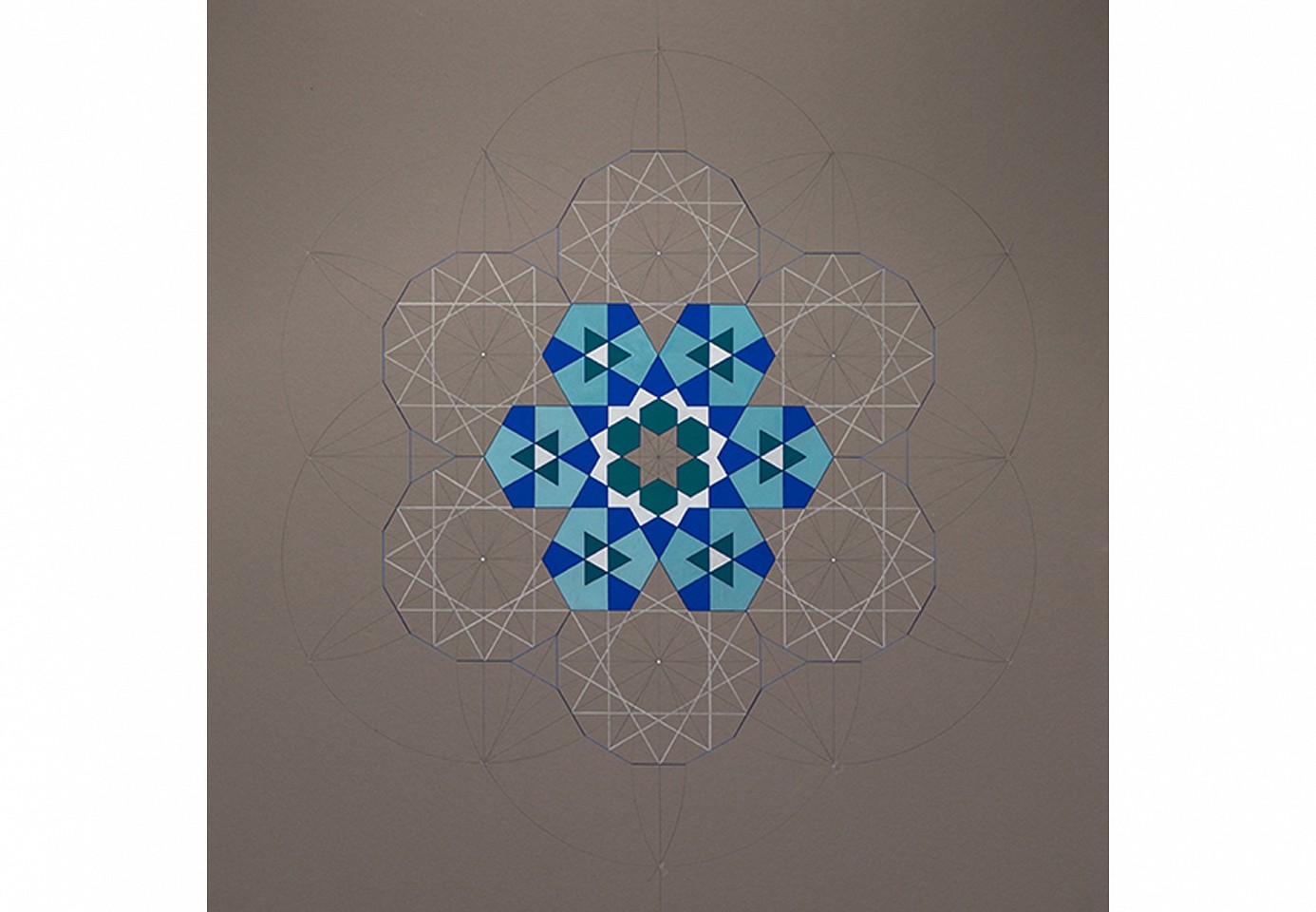

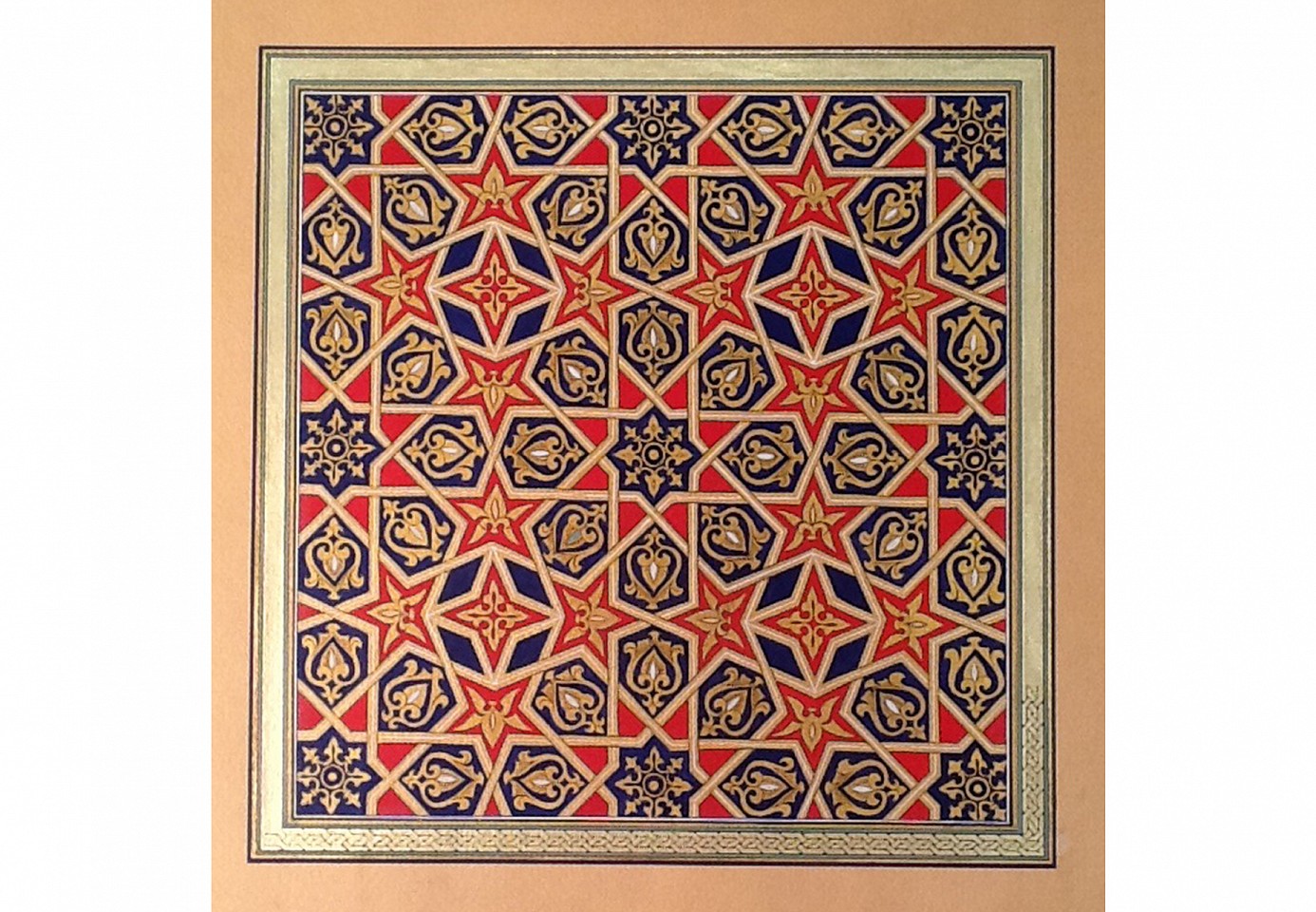

In this artwork Dana Awartani is exploring the history of the Islamic empires in relation to the development of the arts and crafts of the time. This piece is specifically focusing on the art of Quranic illumination, which plays a fundamental role in the Awartani’s art practice as she has currently been training for the past few years in Istanbul with a master in order to receive her Ijaza that will allow her to become a master herself. During her training Awartani is taught Illumination in a purely traditional approach, that predominantly focuses on design, composition and painting techniques and is nearly always detached from any sort of meaning or symbolism. To a certain extent, there are some opinions that view this as an art form that is stuck in time and lacks any sort of innovation or modernity; rather it is an art practice that is confined to very specific guidelines and boundaries due to the respect of its context. However Awartani aims to bridge this gap between the traditional and contemporary, the old and the new in a way that brings both practices together in a harmonies union that will give traditional Islamic illumination a platform in the contemporary world.

The theme of “progressional” drawings and paintings is another fundamental element in Awartani’s practice. She commonly uses this visual language as a way to allow the viewers to take the journey of creating the art works along side with her, which she hopes gives them a deeper understanding and appreciation of the art works..

In “The Islamic Caliphates” Awartani combines her progressional drawings with her illuminations as a vehicle to express the development and evolution of Quranic manuscripts throughout history, and explores how each of the great civilizations have contributed to this art form. This piece also dually depicts the geographical expansion of the religion of Islam over time, starting from the gold circle which represents the birth of the religion in the Hejaz, all the way through to its peak which spans from the far East across to Europe, that is portrayed in the final ‘shamsa’. Each of the designs used throughout the different stages of the artwork, directly correlate with the style of illumination that was invented at the time. Portraying the evolution of this art form from being practically non-existent in the 7th century, mainly due to the fact that there was the fear of allowing anything to intrude upon the holy text of the Quran, which caused illumination to develop in a much more reserved and slower pace then calligraphy, and finally resulting in some of the highly decorative masterpieces you find in the later Islamic empires. Awartani has also chosen to incorporate all the different styles within each other in this progressioanl piece, resulting in the final stage being a combination of all the 8 distinct styles, as a way to also express the universality and highly diverse elements that not only make up the art of Illumination but furthermore is a reflection of the Islamic civilization as a whole, the idea of ‘Tawhid”, or unity within multiplicity which in essence is the core principal of Islam.

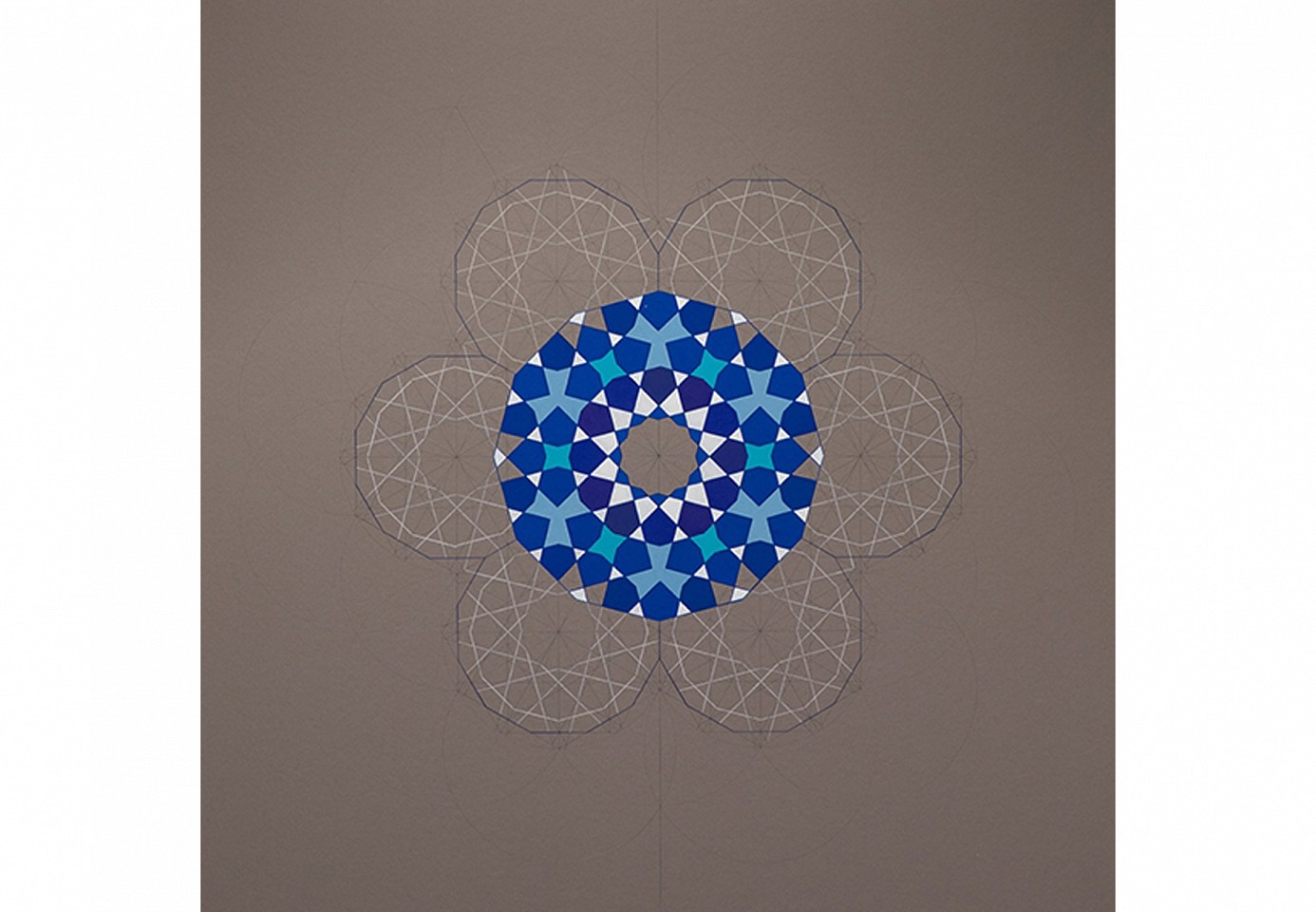

In this piece, Awartani is exploring the subject of “Palindromes” which are words, phrases, numbers or any other sequence of characters that when read backwards or forwards are the same. Palindromes in essence are a form of wordplay that has been used for many centuries dating back to at least 79 AD and the word is derived from the Greek palíndromos, meaning running back again (palín = AGAIN + drom–, drameîn = RUN).

Awartani has been researching the use of palindromes in the Arabic language, more specifically in the Holy Quran, where there only exist two known palindromes that make up one of the many linguistic miracles that can also be found. In this piece she has focused on a verse from Surah Al-Muddaththir (The Cloaked One), which reads as ‘rabbaka fakabbir’ (And Your Lord You Should Glorify, Quran 74:3). Here, reading the sentence backwards including vowels would not create a palindrome. However, taking out consonants only (which are here: r, b, k, f, k, b, r) can clearly create a palindrome.

Continuing with here research and experimentation with developing codes, Awartani has taken the practice of palindromes a step further by converting each letter of the sentence into there numerical value using the Abjadia and then into a symbol that embodies that number. In turn the viewer can decipher this code by firstly looking at how many points/angels each design has and then by looking at how many times that design is multiplied you can tell how many units are in the total sum of the individual letter. As for example the letter “Ra” is expressed by a design that has 2 angels and is painted 3 times which translates into 200, the letter “Ba” uses the same 2 pointed design and is painted once which translates into 2, and the letter “Fa” is expressed using a design that has 8 points and is painted twice, which translates into 80 and so on and so forth.

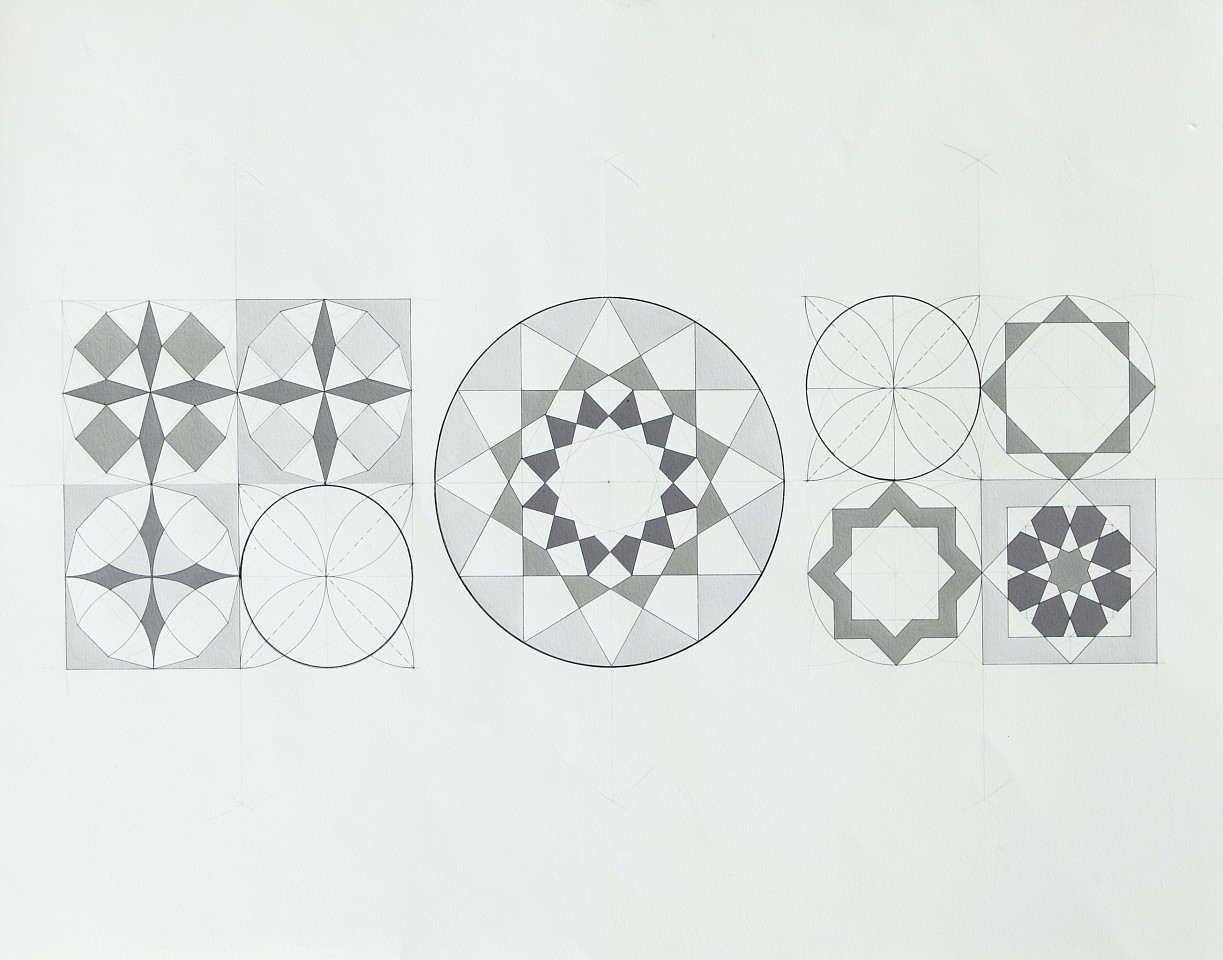

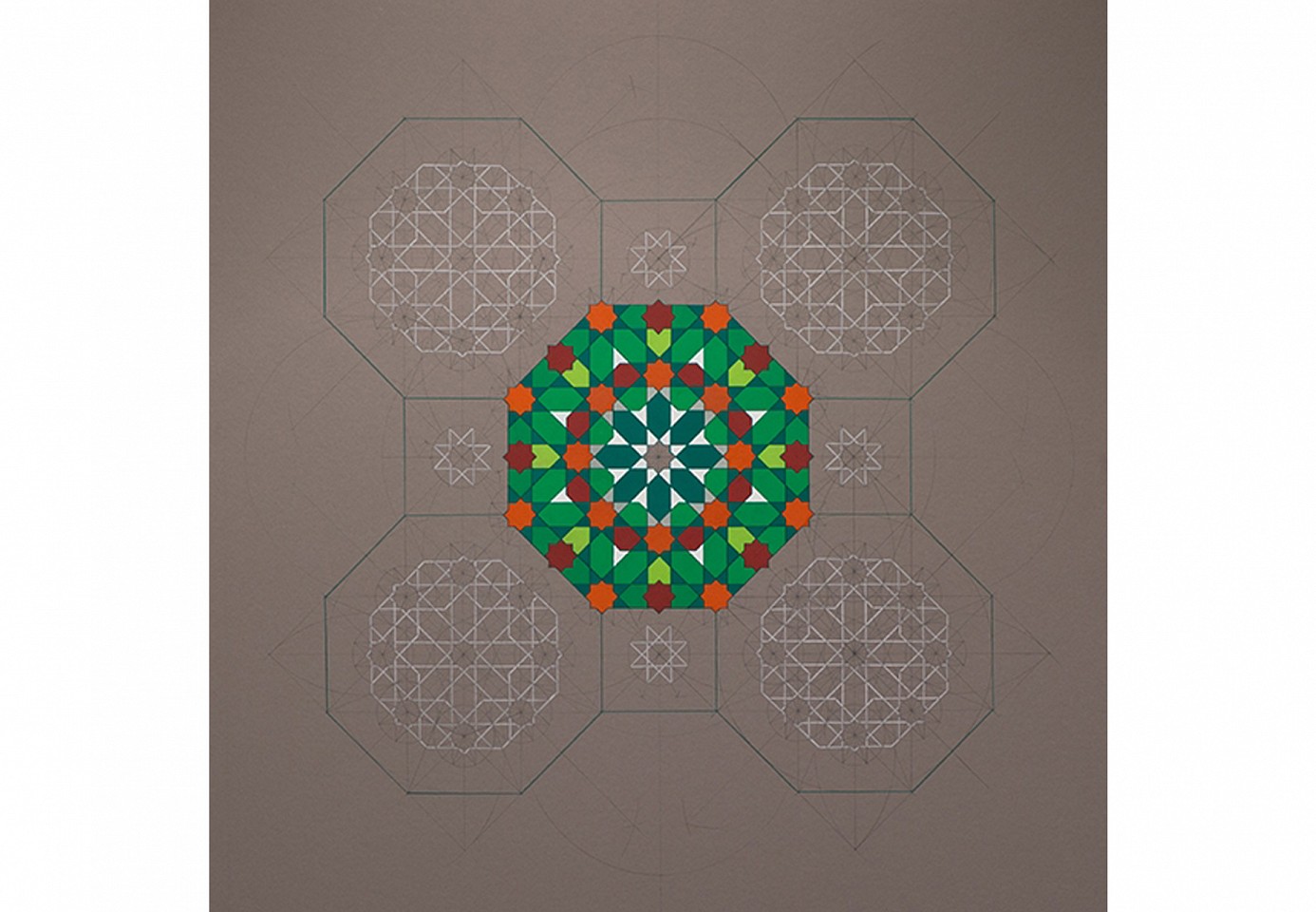

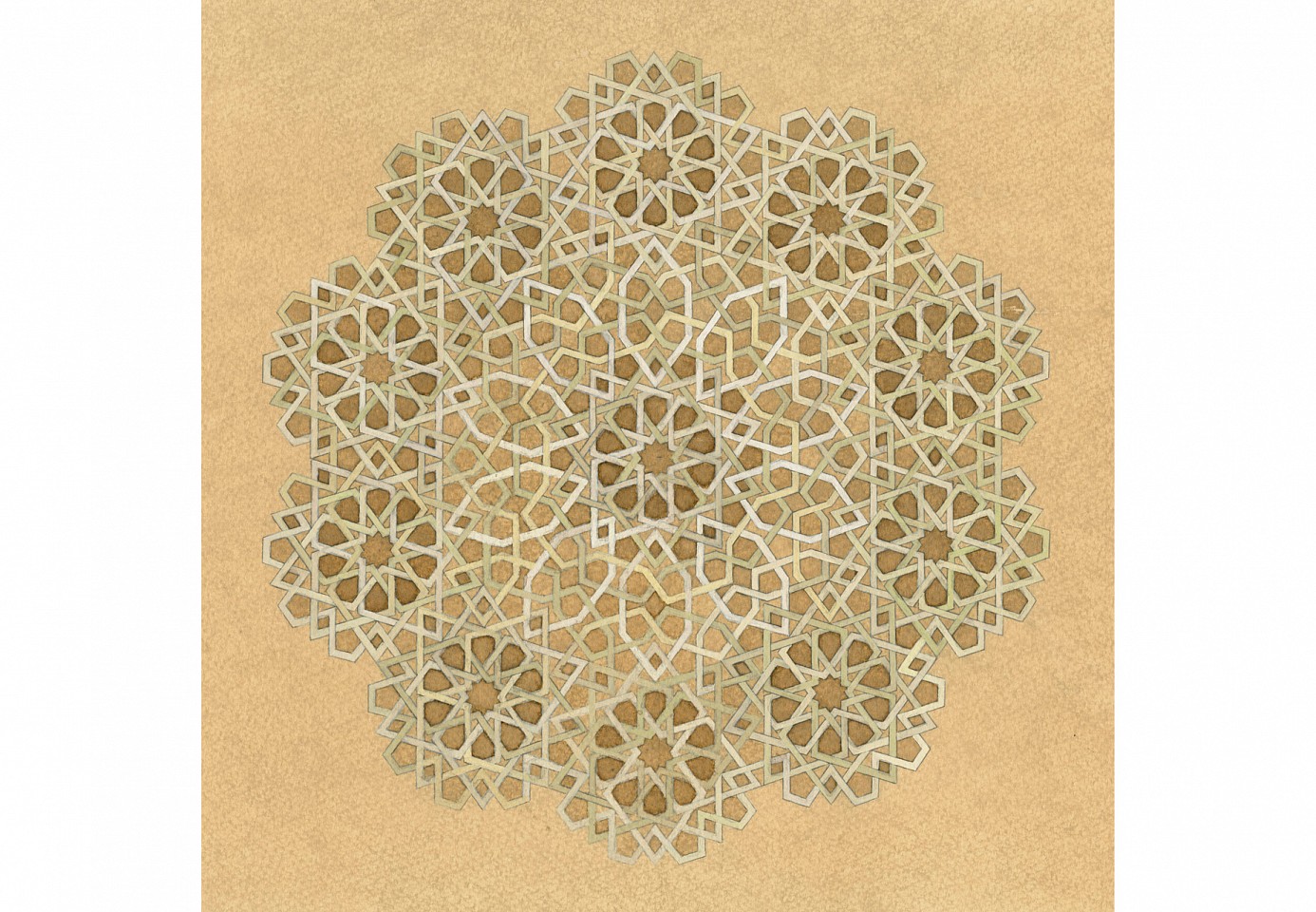

Awartani has created a series of sculptures and drawings based on the Platonic Solids, an ancient study of shapes based on Euclidean geometry.

The platonic solids are the most frequently studied shapes in history. They have been around for thousands of years and geometers have studied their mathematical properties and been fascinated by their inherent beauty and symmetry. What makes them particularly important is that they are considered as the only five ‘perfect’ shapes in three-dimensional space that derive from a sphere. They appear the same from any vertex, their faces are made of the same regular shape, and their vertices represent the most symmetrical distribution of the numbers four, six, eight, twelve and twenty on a sphere.

Awartani has taken direct inspiration from these forms and has translated these three-dimensional shapes into sculptures that examine the dual properties that they share, as each polyhedron has a dual or ‘polar’ polyhedron with faces and vertices interchanged, which is also known as polar reciprocation. By this duality principle each platonic solid has a pair that fit within each other in geometric harmony.

Plato has furthermore attributed the four classical elements (earth, air, fire, water) and the heavens to each shape, based on intuitive justification for these associations. Awartani has taken these principles and translated it in her choice of material, as wood is the only substance that needs all the elements to survive in nature.

In her Five Stages of Grief series, Awartani uses the threads of talismanic references drawn from the Ottoman Empire and rooted in Islam to make connections to lost elements of Saudi heritage. The artist first encountered talismanic shirts in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul – pieces which were once said to protect the Sultans as they wore these kaftans before going to war and their wives during childbirth. The artist has taken original textiles from the Thageef tribe in Saudi, coded patterns which once denoted where a tribe came from. During the founding years of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, all such colourful and distinctive costumes were banished, with the neutral and harmonised black abaya and white kaftan encouraged for men and women, as a way of unifying the tribes. Stitched to the original garments are Awartani’s signature magic squares, where she has taken the five stages of grief and applied one stage to each garment. The artist has referenced to the ancient system used in divination where by the letters of the ‘abjad’ (A system in which each letter in the Arabic alphabet is given a numerical value, giving each name its own unique sum.) are divided into four parts and the seven letters in each part are assigned to one of the elements – air, fire, water and earth. Here she has created her own coded interpretation by attributing one of the elements to a specific stage of grief, with the last being a combination of all the elements, as these garments are intended to be seen as an aid to overcome the various emotions in the process of grieving. In this work, each symbol or letter of the language she has built is stitched into the cloth, the knots and ties intended as a reference to the sorrow implicit when layers of history are wiped out in the name of modernization. At the same time, the juxtaposition of old and new binds Awartani’s own complex reading of the world around her onto the ancient artifacts.

In her Five Stages of Grief series, Awartani uses the threads of talismanic references drawn from the Ottoman Empire and rooted in Islam to make connections to lost elements of Saudi heritage. The artist first encountered talismanic shirts in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul – pieces which were once said to protect the Sultans as they wore these kaftans before going to war and their wives during childbirth. The artist has taken original textiles from the Thageef tribe in Saudi, coded patterns which once denoted where a tribe came from. During the founding years of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, all such colourful and distinctive costumes were banished, with the neutral and harmonised black abaya and white kaftan encouraged for men and women, as a way of unifying the tribes. Stitched to the original garments are Awartani’s signature magic squares, where she has taken the five stages of grief and applied one stage to each garment. The artist has referenced to the ancient system used in divination where by the letters of the ‘abjad’ (A system in which each letter in the Arabic alphabet is given a numerical value, giving each name its own unique sum.) are divided into four parts and the seven letters in each part are assigned to one of the elements – air, fire, water and earth. Here she has created her own coded interpretation by attributing one of the elements to a specific stage of grief, with the last being a combination of all the elements, as these garments are intended to be seen as an aid to overcome the various emotions in the process of grieving. In this work, each symbol or letter of the language she has built is stitched into the cloth, the knots and ties intended as a reference to the sorrow implicit when layers of history are wiped out in the name of modernization. At the same time, the juxtaposition of old and new binds Awartani’s own complex reading of the world around her onto the ancient artifacts.

In her Five Stages of Grief series, Awartani uses the threads of talismanic references drawn from the Ottoman Empire and rooted in Islam to make connections to lost elements of Saudi heritage. The artist first encountered talismanic shirts in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul – pieces which were once said to protect the Sultans as they wore these kaftans before going to war and their wives during childbirth. The artist has taken original textiles from the Thageef tribe in Saudi, coded patterns which once denoted where a tribe came from. During the founding years of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, all such colourful and distinctive costumes were banished, with the neutral and harmonised black abaya and white kaftan encouraged for men and women, as a way of unifying the tribes. Stitched to the original garments are Awartani’s signature magic squares, where she has taken the five stages of grief and applied one stage to each garment. The artist has referenced to the ancient system used in divination where by the letters of the ‘abjad’ (A system in which each letter in the Arabic alphabet is given a numerical value, giving each name its own unique sum.) are divided into four parts and the seven letters in each part are assigned to one of the elements – air, fire, water and earth. Here she has created her own coded interpretation by attributing one of the elements to a specific stage of grief, with the last being a combination of all the elements, as these garments are intended to be seen as an aid to overcome the various emotions in the process of grieving. In this work, each symbol or letter of the language she has built is stitched into the cloth, the knots and ties intended as a reference to the sorrow implicit when layers of history are wiped out in the name of modernization. At the same time, the juxtaposition of old and new binds Awartani’s own complex reading of the world around her onto the ancient artifacts.

The Scroll of The Prophets, Awartani takes the names of all 25 prophets mentioned in the Qu’ran and translates them back to their numerical value using the Abjadia. She then constructs a geometric pattern for each prophet, layering the circles, squares, stars, triangles and hexagonal forms, placing one character (or individual) next to the other in a long scroll. Awartani uses these systems to allow physical manifestations of the prophets in an attempt to transcend the limitations placed on representational forms in Islam, bringing to the fore questions of idol worship.

In this system, each letter in the Arabic alphabet is given a numerical value, giving each name its own unique sum.

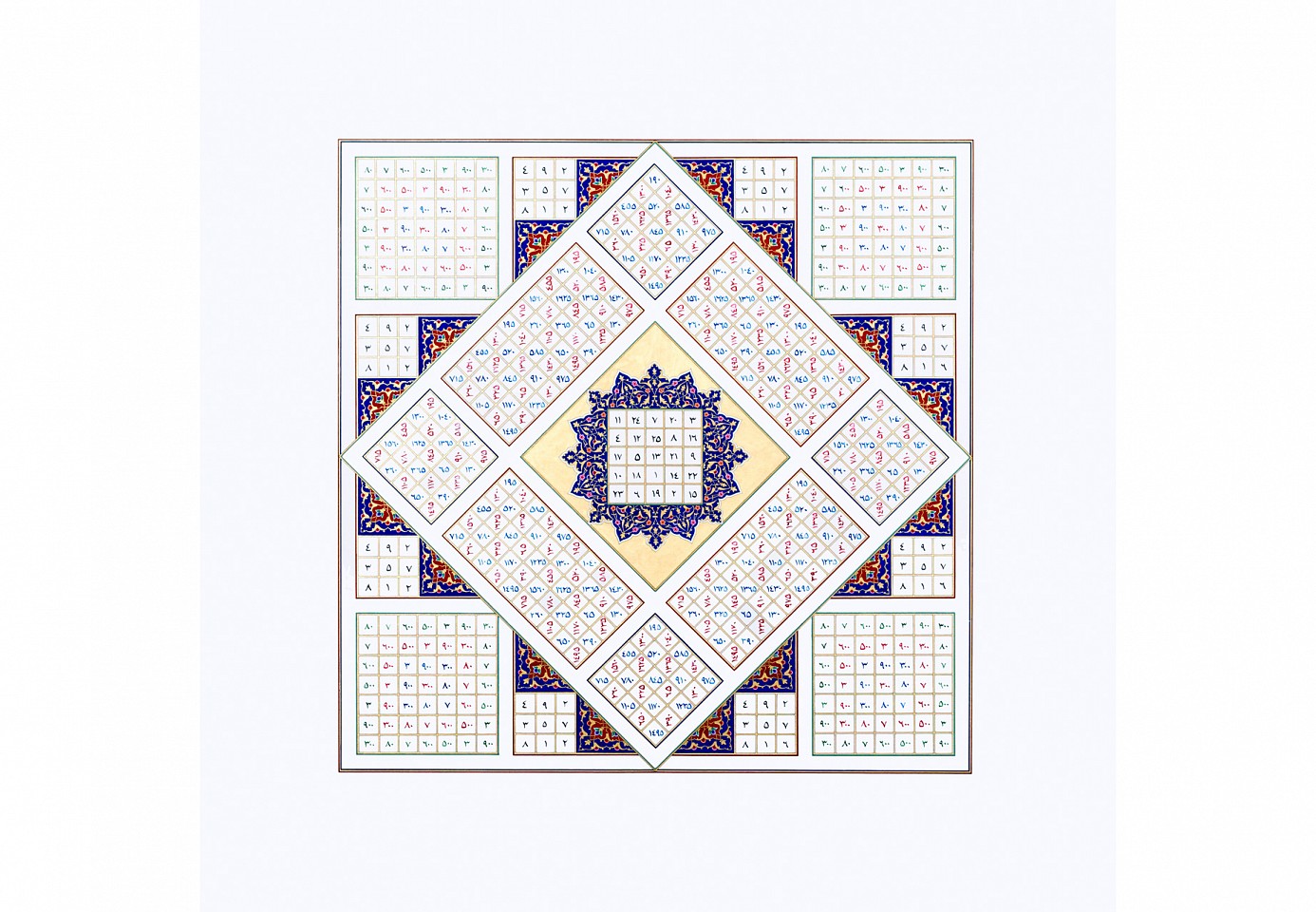

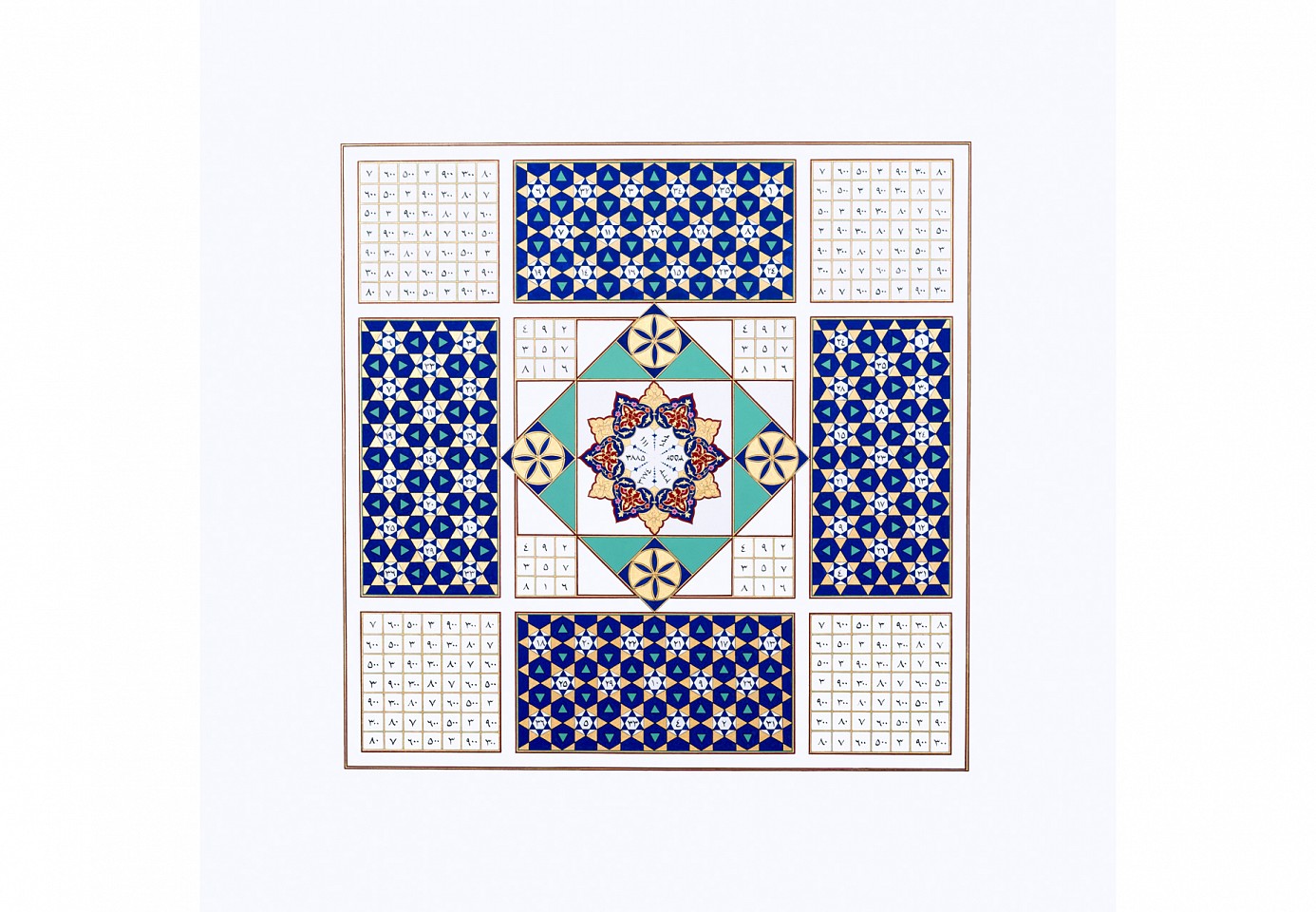

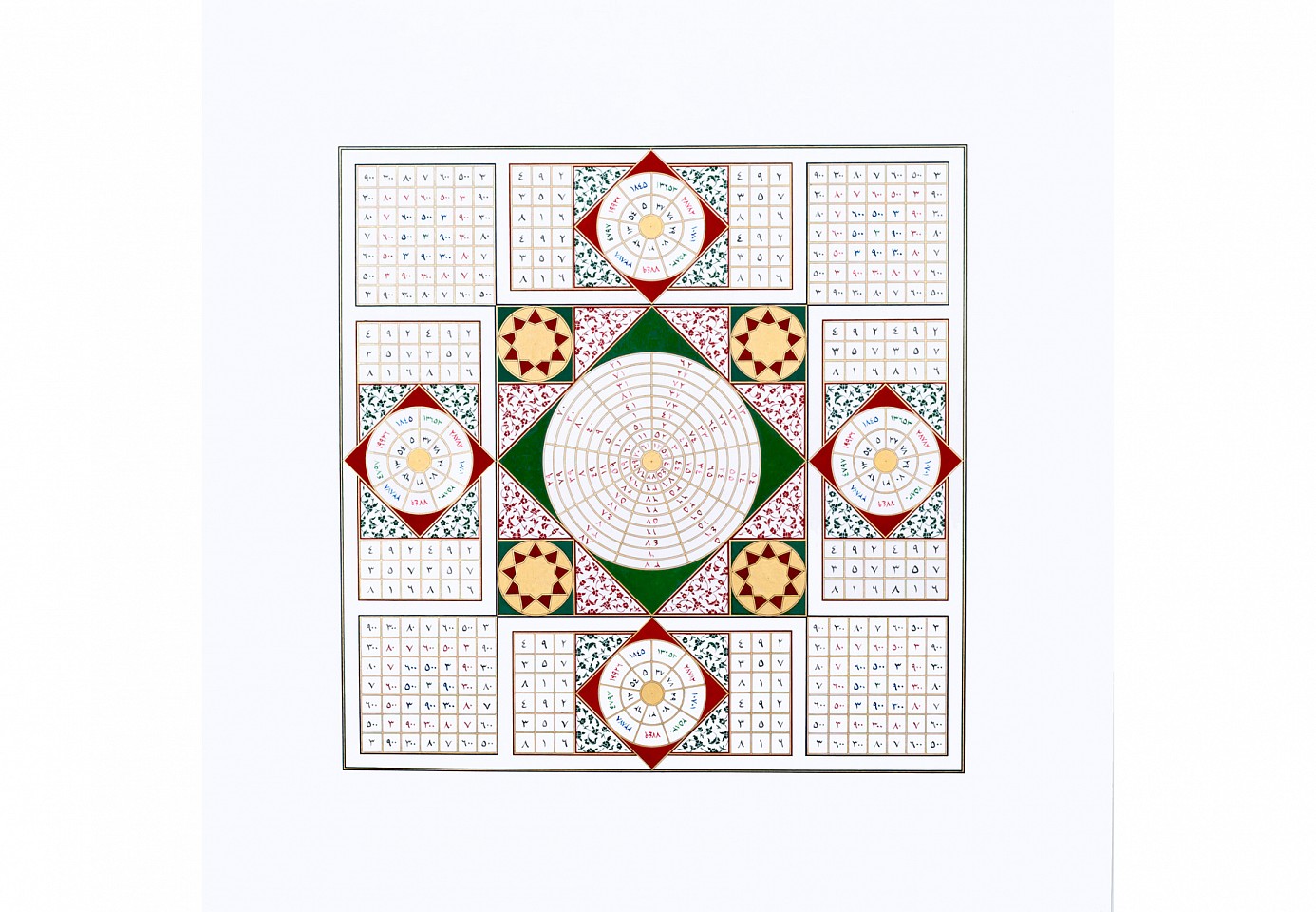

The Heavenly Bodies series combine Awartani’s research into both talismans and Enchanted squares, in particular an investigation into how they were created, used and their spiritual significance. Each of the central squares (from 3 to 9 squared) are affiliated with one of the seven classical planets, a day in the week and an angel – they were also once regarded as a form of protection as well as a source of higher spiritual knowledge through numerology. These works, created using traditional methods and pigments, are structured based on the first square, which sits at the top right of the work and holds the code to deciphering which planet has been illustrated.

Where once these coded paintings might have been used as designs for weavings on clothes, here they work as illuminations, with each of the seven works exploring form, pattern, numerology and mysticism, functioning almost as a manifestation of the artist’s explorations into the threads of divination in ancient Islam. By bringing these early practices into a contemporary and increasingly globalized context triggers questions surrounding the possible reversion to more instinctive rituals along with possible reinterpretations of the Qu’ran.

The Heavenly Bodies series combine Awartani’s research into both talismans and Enchanted squares, in particular an investigation into how they were created, used and their spiritual significance. Each of the central squares (from 3 to 9 squared) are affiliated with one of the seven classical planets, a day in the week and an angel – they were also once regarded as a form of protection as well as a source of higher spiritual knowledge through numerology. These works, created using traditional methods and pigments, are structured based on the first square, which sits at the top right of the work and holds the code to deciphering which planet has been illustrated.

Where once these coded paintings might have been used as designs for weavings on clothes, here they work as illuminations, with each of the seven works exploring form, pattern, numerology and mysticism, functioning almost as a manifestation of the artist’s explorations into the threads of divination in ancient Islam. By bringing these early practices into a contemporary and increasingly globalized context triggers questions surrounding the possible reversion to more instinctive rituals along with possible reinterpretations of the Qu’ran.

The Heavenly Bodies series combine Awartani’s research into both talismans and Enchanted squares, in particular an investigation into how they were created, used and their spiritual significance. Each of the central squares (from 3 to 9 squared) are affiliated with one of the seven classical planets, a day in the week and an angel – they were also once regarded as a form of protection as well as a source of higher spiritual knowledge through numerology. These works, created using traditional methods and pigments, are structured based on the first square, which sits at the top right of the work and holds the code to deciphering which planet has been illustrated.

Where once these coded paintings might have been used as designs for weavings on clothes, here they work as illuminations, with each of the seven works exploring form, pattern, numerology and mysticism, functioning almost as a manifestation of the artist’s explorations into the threads of divination in ancient Islam. By bringing these early practices into a contemporary and increasingly globalized context triggers questions surrounding the possible reversion to more instinctive rituals along with possible reinterpretations of the Qu’ran.

The Heavenly Bodies series combine Awartani’s research into both talismans and Enchanted squares, in particular an investigation into how they were created, used and their spiritual significance. Each of the central squares (from 3 to 9 squared) are affiliated with one of the seven classical planets, a day in the week and an angel – they were also once regarded as a form of protection as well as a source of higher spiritual knowledge through numerology. These works, created using traditional methods and pigments, are structured based on the first square, which sits at the top right of the work and holds the code to deciphering which planet has been illustrated.

Where once these coded paintings might have been used as designs for weavings on clothes, here they work as illuminations, with each of the seven works exploring form, pattern, numerology and mysticism, functioning almost as a manifestation of the artist’s explorations into the threads of divination in ancient Islam. By bringing these early practices into a contemporary and increasingly globalized context triggers questions surrounding the possible reversion to more instinctive rituals along with possible reinterpretations of the Qu’ran.

Dana Awartani presents an immersive installation that combines hand embroidered silk panels with moving sounds of women reciting poetry. Throughout history, the woman’s role has always been underrepresented within art, politics and science. When referencing Arab and Islamic poetry and literature from the region, names such as Rumi, Hafez and Ibn Arabi most often spring to mind. This body of work sets to lift the veil on a whole cast of radical female poets that range from the pre Islamic times up to the 12th century. The poems and poetesses hail from a wide range of cultures within the Arab world and explore the themes of love, lust and longing.

The presence of geometric layered panels throughout this work references the ‘Jali’ screen, which is characteristic of the Islamic tradition and more specifically in this piece, Mughal India, and they were typically used to shield women from the male gaze. In this case, the artist has reinvented these screens by using embroidery in collaboration with craftsmen in India, and has chosen a specific stitch called ‘Aari’ which derived from the Mughal period. Awartani was more specifically inspired by a figure named Nourjehan who was the wife of a Mughal Emperor and she partook a leading yet hidden role in governing the state while being forced to sit behind a Jali screen, whispering commands into her husband’s ear.

The work juxtaposes theory and execution, as the installation is one that evokes serenity and contemplation interjected with radical words within the space.

The recitation of the poetry is done in its original language of Arabic, using the voices of Sara Abdu, Fatima Al Banawi, Najla Al Bassam, Ahd Kamel and Zahar Al Sayed - modern day Saudi women who embody the spirits of these forgotten poetesses, strong, empowered and inspirational.

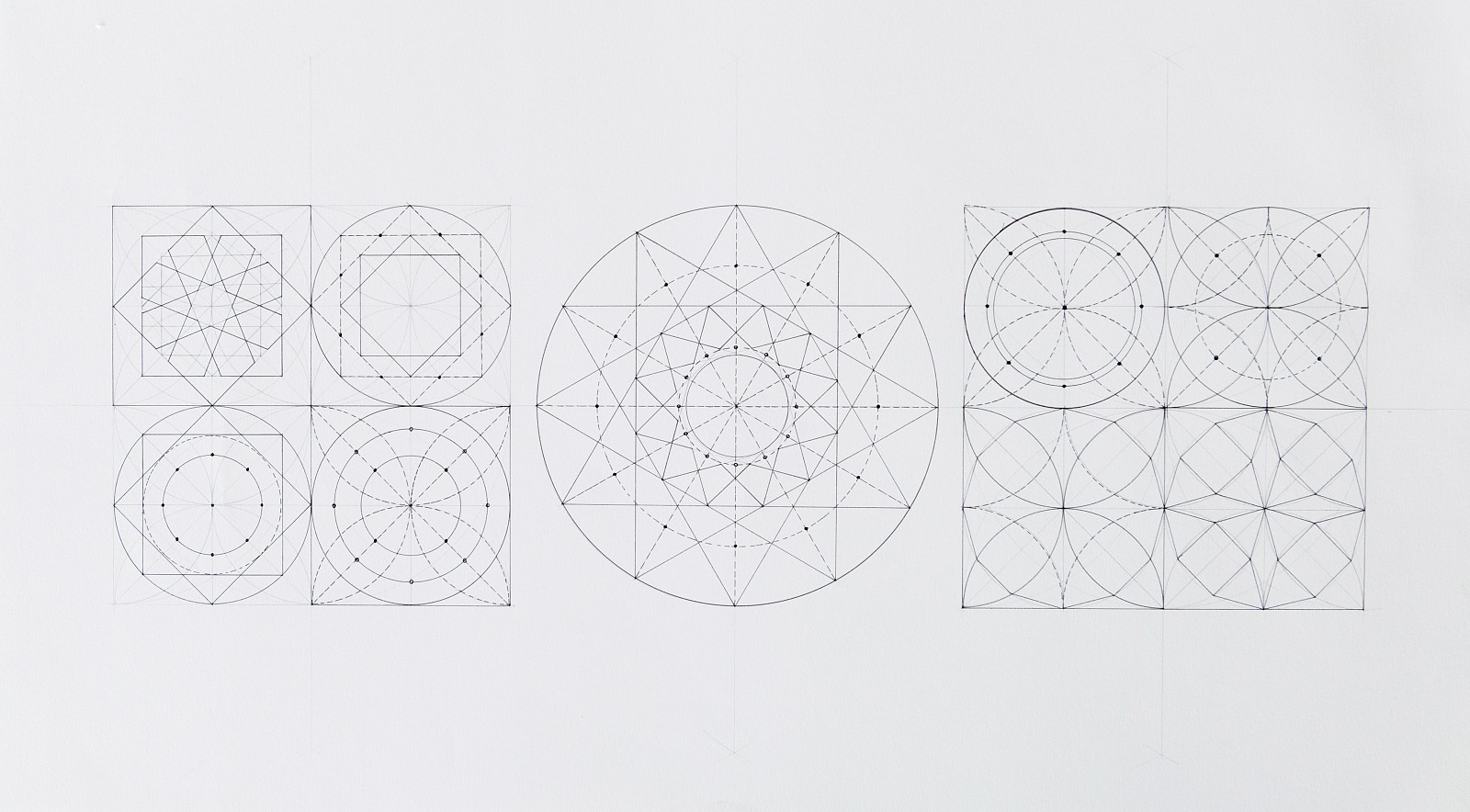

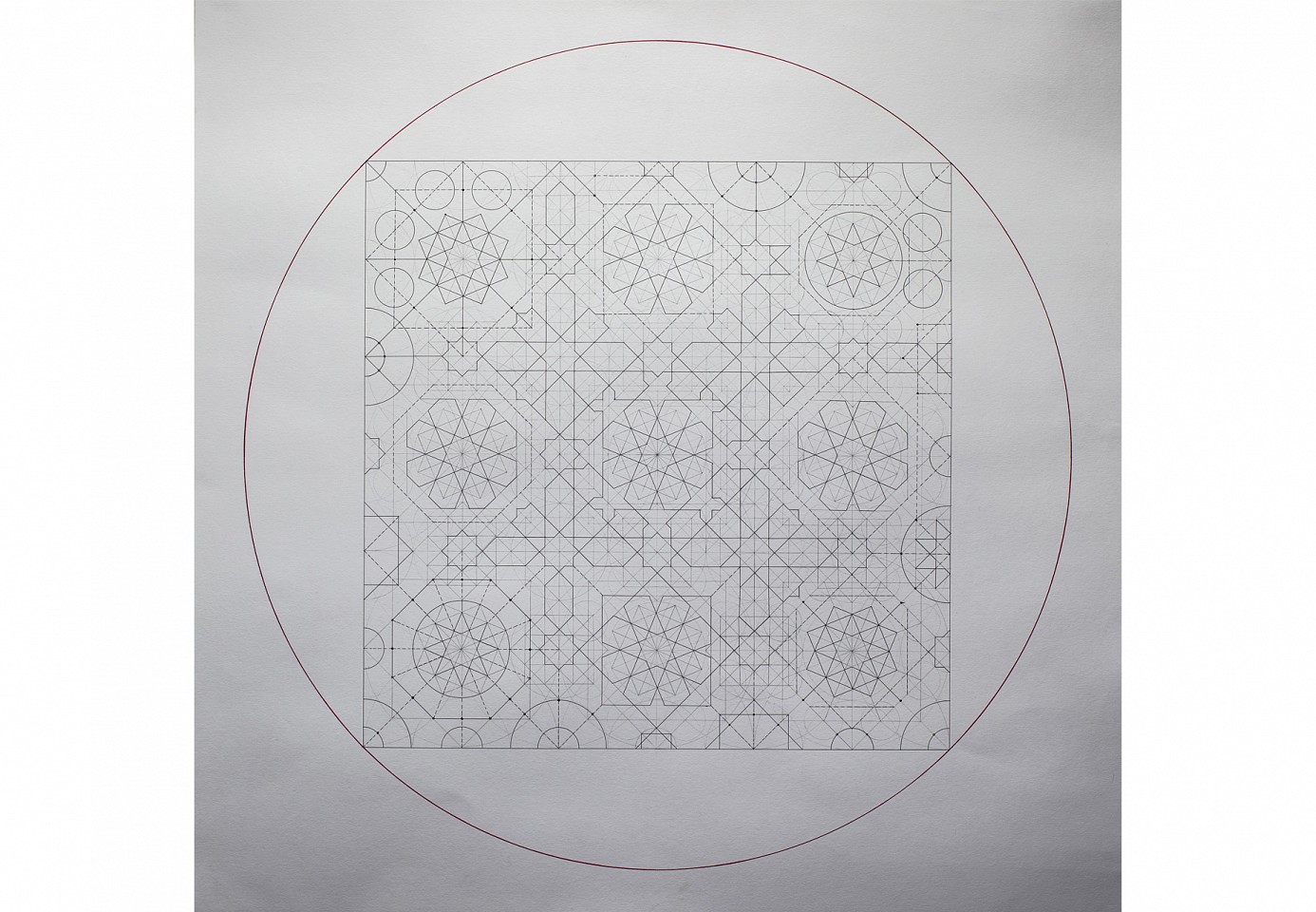

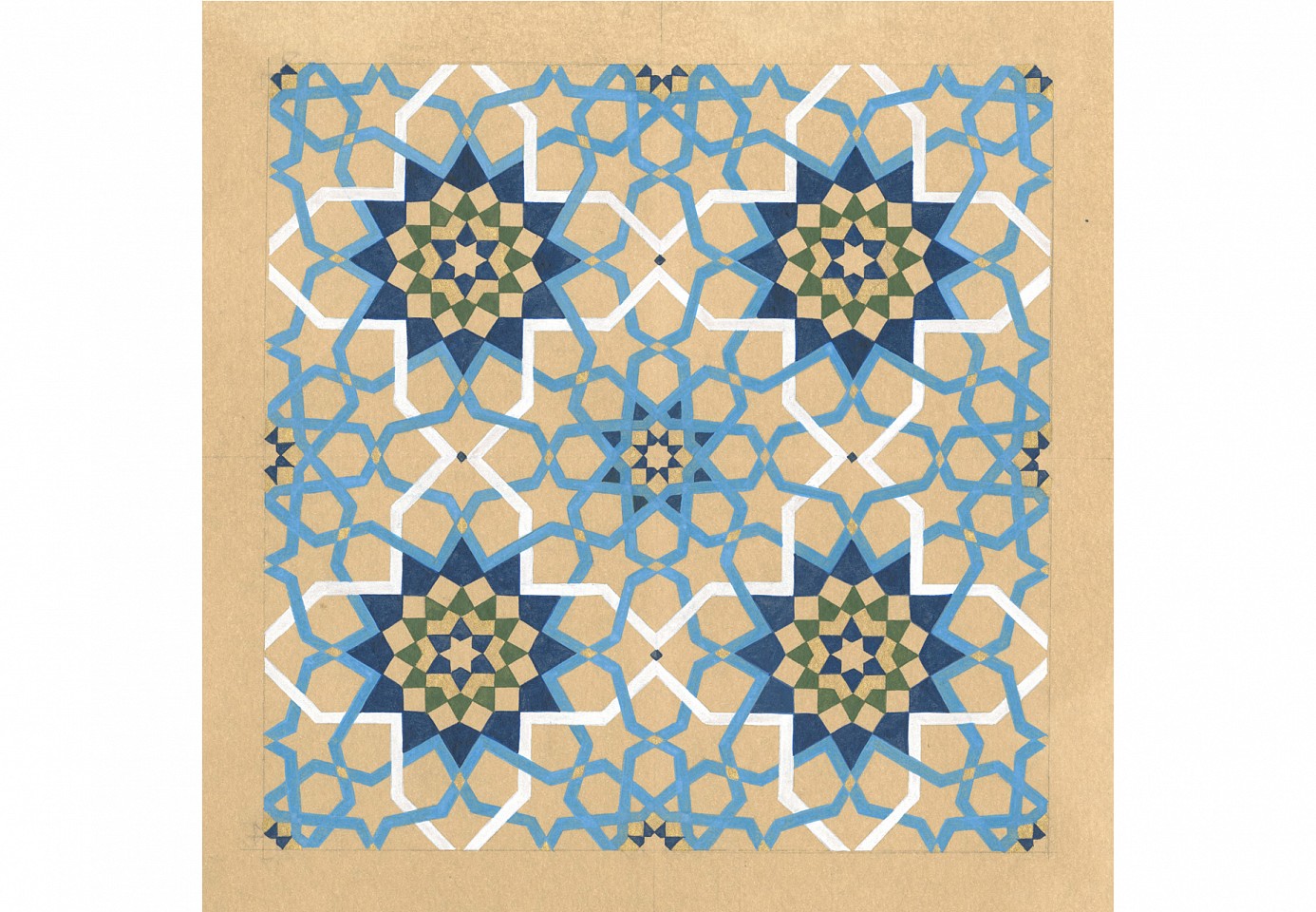

Through highly studied, focussed, and skilled deployment of traditional techniques, Dana Awartani extends interpretive legacies. She masters historic and symbolic playgrounds to explore and sustain revered structural traditions. Her innovative approach to these visual codes is epitomised by her Abjad Hawaz concept. Through it, she evolves and maps the complexities of Sufi and Islamic scholarly traditions, opening up contemporary spaces for intuitive comprehension of linguistic and semantic systems, revivifying their potent potential for spiritual engagement.

She works within the Sufi tradition where symbolism is an essential means to approach and intuit awareness of the Eternal. Sufi poetry and teachings are layered with evocative symbols that strive to inform and awaken different levels of intellect, being, and understanding. Transcending strict narrative structures, the texts are steeped in complex sign systems manifested through literary devices such as double-entendre, root-word resonance and numerology.

The traditions Awartani inherits from have their legacies in more ancient practices: the Islamic world was heir to an alphabetical numerology that had been in play for many centuries. In this system, each letter of the alphabet can be alternatively expressed by a number. A common practice in Arabia, letters would naturally be read simultaneously as words and as a collection of numbers. Within this context, the miracle of the Quran is made further evident through the eloquent and highly complex manifestation of such intricate numerological systems.

The study of abjad, particularly its exceptional rendering in the scripture, is part of a great scholarly tradition called the science of letters (ilm al-huruf). Concerned not only with numerological systems, scholars of this science also investigate letter shapes and forms, as well as their cosmological significance. The science of numbers stands above nature as a way to approach a comprehension of unity or ‘tawhid’, an absolute central principle of Islam pertaining to the indivisible oneness of God. In this vein, numbers are the principle of beings and the root of all sciences, the first effusion of spirit upon soul, whereas geometry is the expression of the ‘personality’ of numbers.

It is within this rich reverential legacy that Awartani evolves Abjad Hawaz, a singular system of visual coding that draws on her deep understanding of geometry and illumination. She builds upon the ancient numerical system, expansively divining an aesthetic language that revivifies the abjad and insists on its relevance. This visual language possesses a striking immediacy in its capacity to extrapolate symbiotic meanings and forms. This is a co-dependency inherent in geometry where the form is the result of a numerical expression – without which geometry would not exist. Skillfully deploying her deep understanding of traditional geometric expressions, Awartani abstracts and imparts pure meaning using the method to create a harmonious and formal expression of complex notions that are difficult to succinctly synthesise.

Awartani’s visual language invites the viewer to participate in its coding and meaning-making, the direct translation of number into form becoming decipherable even for the uninitiated. In the system, each shape’s angles and repetitions equate to the numerical value or sum of the individual letter. So, as we engage with the form, the sense of the system emerges – we see that alef is not only shaped like the number one but is the number one. From here, a further kind of comprehension grows, with historic, scientific and mathematical symbolism potently coalescing as they are woven into the invested values of Awartani’s focussed expression. Understanding expands and we are able to appreciate alef as the original letter, the representative of the principle of unitary being. Accordingly, Awartani achieves a concurrent expression of this number, letter, and concept with a circle – the symbol of unity and creation. The other letters of the alphabet are said to have evolved from the letter alef into the variety and multiplicity of the alphabet, which for the hurufis, represents the cosmos. In the geometric tradition, the circle is the creator and originator of all geometry, where every design starts and finished within the circle.

A highly trained practitioner of traditional Islamic arts, Awartani deploys skilled techniques from within ancient systems. In this way, she engages with the systems in their most essential form, tapping their invested power to bring it into a contemporary moment. Through these pure interrogations, Awartani invigorates the traditional, mapping and deconstructing value to demonstrate the potential and enduring relevance of a highly powerful visual language capable of concurrently articulating deep truths of mathematics, science, history, and spirituality. As such, her work becomes a vigorous rebuttal that counters the uninformed perspectives that dismiss these practices merely as a decorative art

or ‘craft’.

![<p><span class="viewer-caption-artist">Dana Awartani</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-title"><i>All [heavenly bodies] swim along, each in its orbit</i></span>, <span class="viewer-caption-year">2016</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-media">Mixed Media</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-dimensions">150 x 150 cm</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-aux"></span></p>](/images/29138_h960w1600gt.5.jpg)