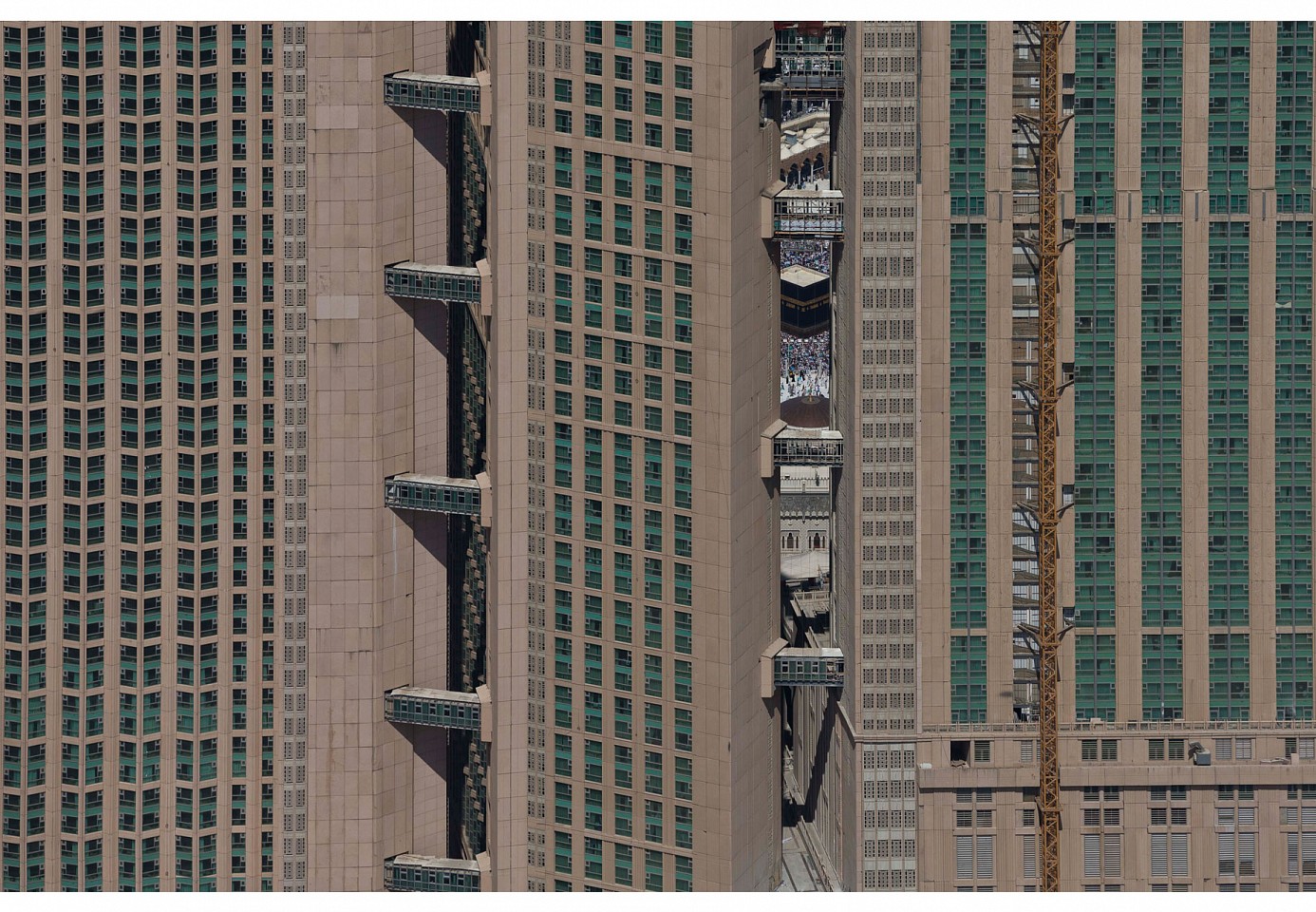

Ahmed Mater

Abraaj Al Bait Tower, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0023

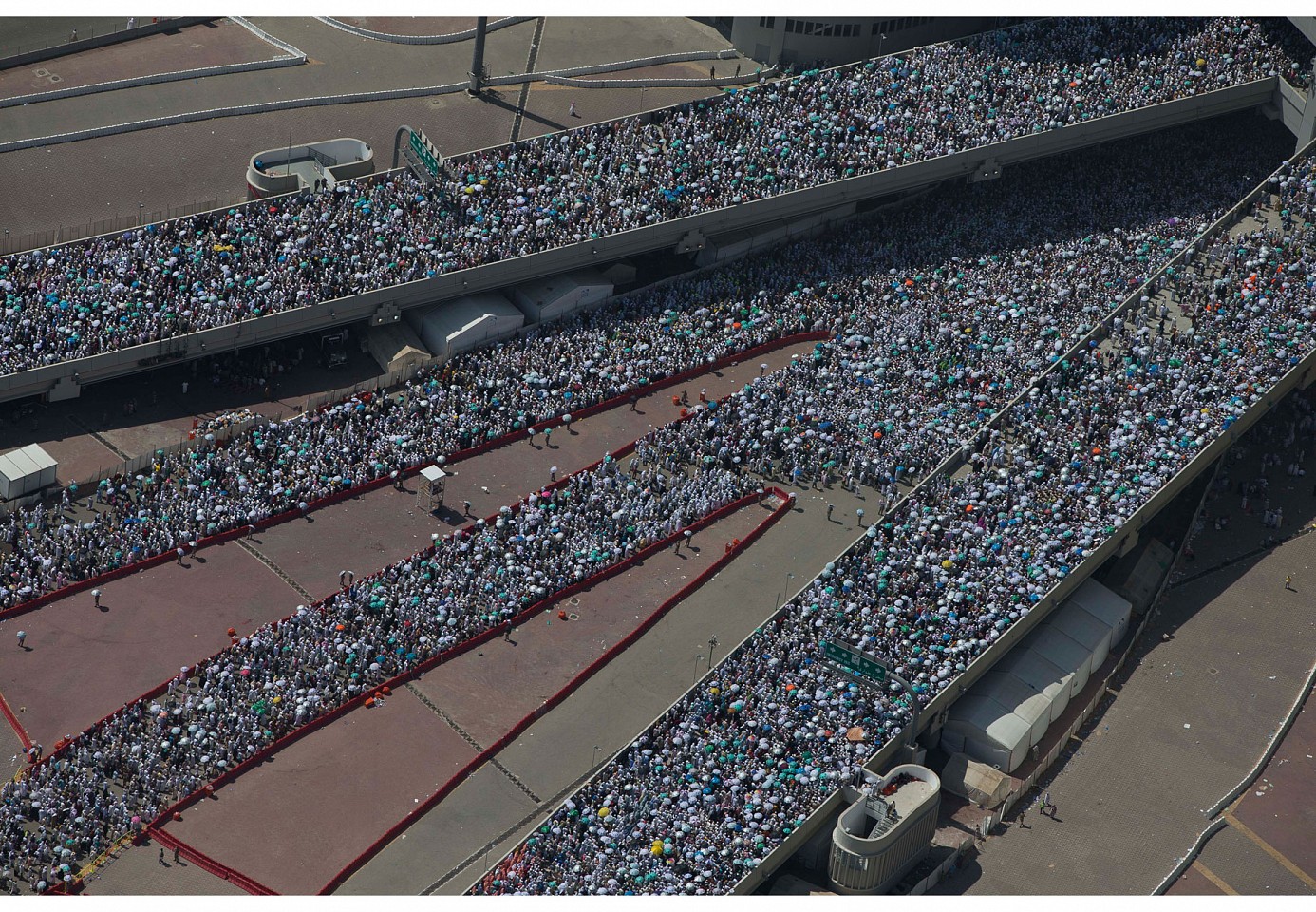

Ahmed Mater

Human Highway, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0043

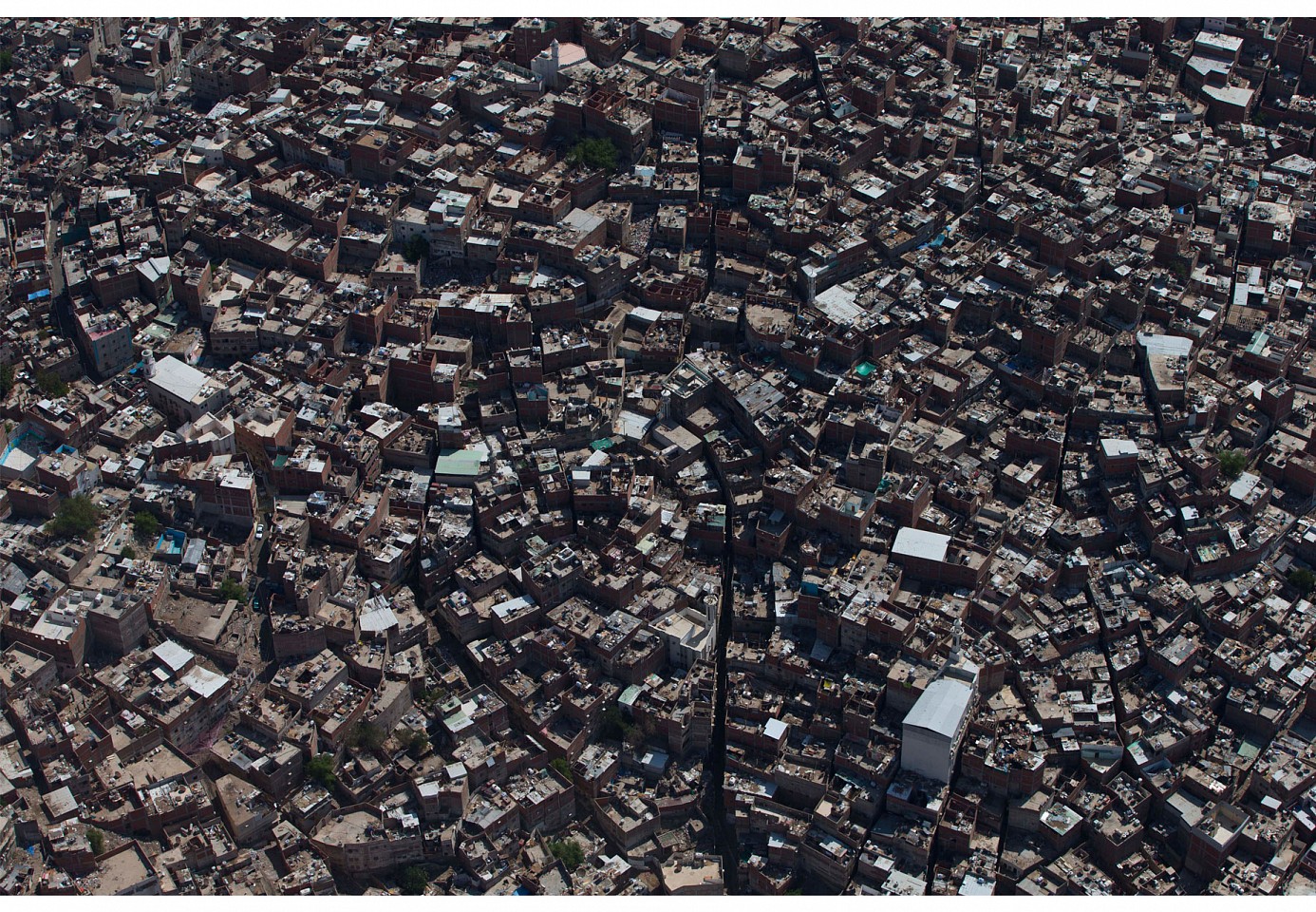

Ahmed Mater

Al Mansur District, 2012

Laserchrome print on KODAK real photopaper

140 x 200 cm (55 1/8 x 78 3/4 in.)

Edition of 5; From Desert of Pharan series

AHM0033

Ahmed Mater

View Masters and Slides Installation, 2014

3 various View Masters

24 C- prints, 40 x 40 cm each

Edition of 10 Image courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation

AHM0204

Nasser Al Salem

And Also In Your Own Selves, Do You Not See?, 2012

laser-cut stainless steel mounted on 20 mm acrylic20 mm acrylic

180 x 105 x 10 cm

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

NAS0084

Nasser Al Salem

They Will Be Seen Competing In Costructing Lofty Buildings, 2014

Concrete Sculpture

Edition of 5

NAS0147

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

-Naima Rashid

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

- Naima Rashid

The lifeline of history is like the lifeline of a river – there is one central artery and thousands of other tributaries, some as thin as hair, branching every which way. The stories of history, like the stories borne by rivers, run as much in the central gushing aorta as in the branching veins, but the official records of history, the narratives that are passed on to posterity, often record only the primary narrative and gloss over the others. Sometimes, the artist has to step in as an alternative historian, and fill up these cracks in truth, cementing the fissures with missing links and pieces, and taking on roles as varied as scribe, chronicler, documentarian or the collective conscience of a people in a certain time and place.

At this point in time, Saudi Arabia is a node of such rapid change that it often baffles comprehension. A taste for secrecy and for avoiding its own truths often frustrates even the best-hearted attempts at documentation. Any man who leaps into the fray to challenge or truthfully complement the overlooked pockets of truth must be credited with courage. In ‘Artificial light’, the artist documents what he calls ‘an unofficial history of the urbanization of Makkah’. While Makkah’s shape, its scope and future change beyond recognition in a central sphere of development where the old and new symbol (the Kaa’ba and the Makkah Clock Tower’) confront each other directly, the shockwaves from this heated centre of conflict spread well into the fringes, into the houses, hearts and minds of the millions that absorb and live this irreversible change from the inside out. The transformation of Makkah is mapped upon their hearts and minds, their daily thoughts, in the way they have thought and will continue to think about their lives, in the way they evaluate and assess their past and in the way they project and plan their future. Their destinies and those of the city are inseparable. In this project, among other things, the artist takes it upon himself to collect these tertiary narratives in the form of audio and video documentaries. For the half-blind of the world, who will not seek beyond the truth of a google search, the narrative of the urbanization of Makkah is a narrative of concrete, but for the spiritually awake and the morally courageous, any narrative of change and transformation is read through stories of humans, not through the weight of concrete and the height of towers. It always has and perhaps, always will be, the moral responsibility of the artist to resurrect the human underbelly of this narrative of concrete and keep it from being buried under the rubble and forgotten from memory.

In the mind of the world, Makkah is a symbol more than a city, and like all symbols, an image of Makkah is not just an image. It is an image which is always read and interpreted by believers and non-believers alike. Layers of meaning, homage, veneration, significance, and history have been kneaded, over timeless decades, into what is a continuous visual narrative – the real or imagined story behind the image, the surcharge of symbolism it has accumulated over the years, and the feelings it evokes in the beholder. Makkah has never been seen neutrally, it has always bathed in its own sacred halo. It has always been seen from a standpoint of emotional and religious fervor, and the visual narrative available to us uptil now has always confirmed the vantage-point of Kaaba in this tale. Kaaba has dominated the visual narrative of Makkah (indeed, the two are almost synonymous to many) - humbly, but regally owning its position as a source, as a self-assured but unassuming quiet black monarch.

The sequence of stills in ‘Artificial Light’ is the latest addition to this narrative. Instead of taking it forward along the older axis of Kaaba’s sanctity and predominance as a sacred symbol, it completely inverts the narrative - a more glamorous, gaudily clad monarch now holds court in the central arena. The trivialization of the Kaaba is, before anything, a physical jolt, an uprooting of a familiar point of focus for the vision. The actors in this new chapter are automatons, electronic limbs of giant-sized machines, superimposing construction grids, and contractual labourers, and the sovereign is, the pictures seem to suggest, the new high rise, doubtless an ode to man’s will to compete and command. As our familiar associations with the Kaaba are shattered, we become alienated from the meaning of Kaaba. We see a Kaaba looking almost done in by the menacing limbs of construction machines, no longer secure about being the natural or only focus. Other pictures are taken from sly perspectives that posit the Kaaba within more consumerist and materialist contexts, forcing us to rethink and re-evaluate its meaning, replacing the comfortable full-stops in our mind with question marks.

The truth is that for Saudi Arabia and Saudis, Makkah is not an extraneous symbol separate from themselves, it is a part of their national and individual ethos. It is the existential denominator of their being and existence. How will the revamped Makkah affect their sense of self and worth? Will it make them disoriented? How culturally appropriate is the glamorous new tower? For the Saudis, is it a broche or an eyesore? To what extent can they identify with it? Does it repel them or are they indifferent to it?

The questions are endless. They all must be answered, but first, they must be faced. In times of change like the ones we live in, art ceases to mean beauty, it means tact, nerve, and the courage to grapple with winds of change. The artist, in these times, is a shower of mirrors. Sometimes, art could simply mean arranging mirrors in such a manner that different views of the same reality face us wherever we turn, and the full picture of truth is sealed from different angles, so that we are trapped with the most burning questions of our beings and surroundings with no way to escape. The changing face of our present is a burning question, for our future depends on it.

-Naima Rashid

View Master slides 1960-80 / 1980-2000 and 2000-2020

Images taken from Makkah’s most widely circulated pilgrim keepsake. Made in China since the pre-1960s they have been shipped over in their thousands along the same silk route that has been central to cultural interaction from East to West since 206 BCE. These same View Finders, once bought on Al Khalil Road in Makkah, are then disseminated through the hands of the pilgrims to every corner of the world. The View Finders and their images, are not only visual portals to a city that bristles under the weight of its own dramatic symbolism but a reflection of a site revered by millions created with the specific task of triggering fantasies of a pilgrimage to Makkah and all it implies. As objects, the View Finders embody these dreams, whilst the collection of images, once released from the limitations of their intended form, are transformed. They become not only social documentation but pertinent and poignant signifiers of specific times and places, drawing on collective history, iconography and memory, of a site that is at once the most visited yet the most exclusive in the world.

Abbas Akhavan, Parastou Forouhar, Babak Golkar, Dor Guez, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, Hazem Harb, Susan Hefuna, Bouchra Khalili, Sophia Al Maria, Ahmed Mater, Nasser Al Salem

The rising cities of the Gulf region on the one hand and conflicts in the Middle East that are carried out in the public arena on the other are ever-recurring themes of media coverage. Both in terms of their content and through their manipulative aesthetic the often extreme images shape our western view of the region.

The exhibition counters these images with artistic works that show a different, more multifarious approach to reflecting on social conditions. For it is also possible to perceive the change in this region as a re-structuring of the global order. Ultramodern urban construction and mass demonstrations are subjects that point to tradition and global aspirations. There is a noticeable expansion of artistic image-making to include overriding themes: that is, space itself and the features and possibilities of public space, as the individual positions him- or herself within society which sets limits and defines maneuvering room, both literally and figuratively.

The collecting and archiving of objects which increase in value due to their personal selection and presentation describes a subjectively structured and sometimes biographical narrative style, which as a result reflects and condenses collective historiography. There is a biographical element involved here, too, as some of the artists included in the exhibition do not live in their native country: their view from the outside allows them to subject their own experiences to scrutiny and to process such analytical reflections in artistic terms.

The artists included in the exhibition are active internationally. Beyond regional references, they present their take on social issues. Their view from the outside allows them to subject their own experiences to scrutiny and to process such analytical reflections in artistic terms. The exhibition title refers to the concept of „grounding“ in communication theory, which posits that communication partners share mutual knowledge, making it possible for a dialogue to lead to a successful result.

The exhibition is accompanied by a bilingual (German/English) catalogue that examines this aspect in more detail and introduces the artists based on individual entries. The catalogue will be publishd by the reknown art publishing house Hatje Cantz. A interdisciplinary programme will accompany the exhibition as well.

An Exhibition of the Museum Villa Stuck

Curated by Verena Hein