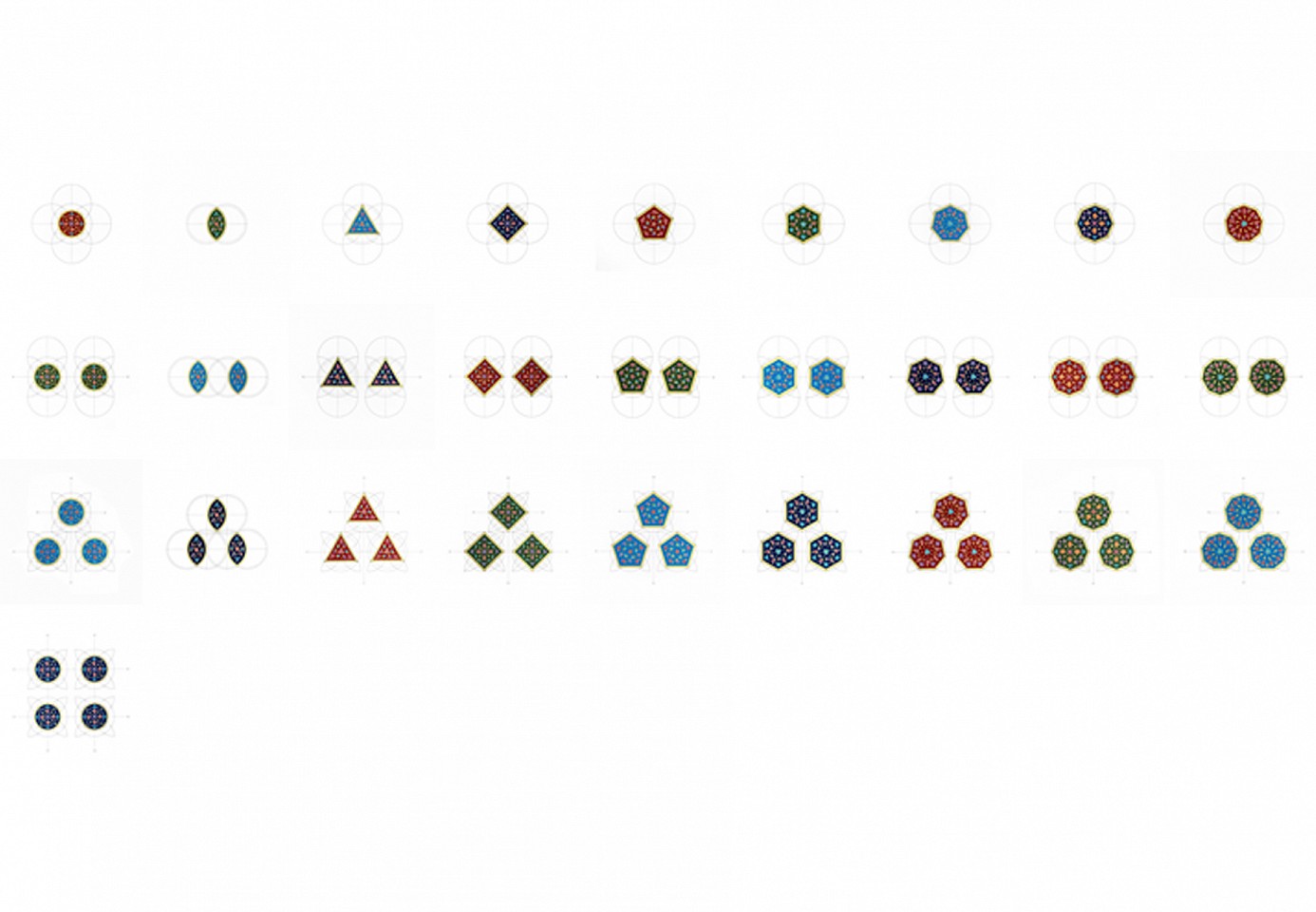

Dana Awartani

Abjad Hawaz series, 2016

Shell gold, ink and gouache on paper

Dana Awartani

All [heavenly bodies] swim along, each in its orbit, 2016

Mixed Media

150 x 150 cm

![Dana Awartani, All [heavenly bodies] swim along, each in its orbit

2016, Mixed Media](/images/29138_h125w125gt.5.jpg)

Through highly studied, focussed, and skilled deployment of traditional techniques, Dana Awartani extends interpretive legacies. She masters historic and symbolic playgrounds to explore and sustain revered structural traditions. Her innovative approach to these visual codes is epitomised by her Abjad Hawaz concept. Through it, she evolves and maps the complexities of Sufi and Islamic scholarly traditions, opening up contemporary spaces for intuitive comprehension of linguistic and semantic systems, revivifying their potent potential for spiritual engagement.

She works within the Sufi tradition where symbolism is an essential means to approach and intuit awareness of the Eternal. Sufi poetry and teachings are layered with evocative symbols that strive to inform and awaken different levels of intellect, being, and understanding. Transcending strict narrative structures, the texts are steeped in complex sign systems manifested through literary devices such as double-entendre, root-word resonance and numerology.

The traditions Awartani inherits from have their legacies in more ancient practices: the Islamic world was heir to an alphabetical numerology that had been in play for many centuries. In this system, each letter of the alphabet can be alternatively expressed by a number. A common practice in Arabia, letters would naturally be read simultaneously as words and as a collection of numbers. Within this context, the miracle of the Quran is made further evident through the eloquent and highly complex manifestation of such intricate numerological systems.

The study of abjad, particularly its exceptional rendering in the scripture, is part of a great scholarly tradition called the science of letters (ilm al-huruf). Concerned not only with numerological systems, scholars of this science also investigate letter shapes and forms, as well as their cosmological significance. The science of numbers stands above nature as a way to approach a comprehension of unity or ‘tawhid’, an absolute central principle of Islam pertaining to the indivisible oneness of God. In this vein, numbers are the principle of beings and the root of all sciences, the first effusion of spirit upon soul, whereas geometry is the expression of the ‘personality’ of numbers.

It is within this rich reverential legacy that Awartani evolves Abjad Hawaz, a singular system of visual coding that draws on her deep understanding of geometry and illumination. She builds upon the ancient numerical system, expansively divining an aesthetic language that revivifies the abjad and insists on its relevance. This visual language possesses a striking immediacy in its capacity to extrapolate symbiotic meanings and forms. This is a co-dependency inherent in geometry where the form is the result of a numerical expression – without which geometry would not exist. Skillfully deploying her deep understanding of traditional geometric expressions, Awartani abstracts and imparts pure meaning using the method to create a harmonious and formal expression of complex notions that are difficult to succinctly synthesise.

Awartani’s visual language invites the viewer to participate in its coding and meaning-making, the direct translation of number into form becoming decipherable even for the uninitiated. In the system, each shape’s angles and repetitions equate to the numerical value or sum of the individual letter. So, as we engage with the form, the sense of the system emerges – we see that alef is not only shaped like the number one but is the number one. From here, a further kind of comprehension grows, with historic, scientific and mathematical symbolism potently coalescing as they are woven into the invested values of Awartani’s focussed expression. Understanding expands and we are able to appreciate alef as the original letter, the representative of the principle of unitary being. Accordingly, Awartani achieves a concurrent expression of this number, letter, and concept with a circle – the symbol of unity and creation. The other letters of the alphabet are said to have evolved from the letter alef into the variety and multiplicity of the alphabet, which for the hurufis, represents the cosmos. In the geometric tradition, the circle is the creator and originator of all geometry, where every design starts and finished within the circle.

A highly trained practitioner of traditional Islamic arts, Awartani deploys skilled techniques from within ancient systems. In this way, she engages with the systems in their most essential form, tapping their invested power to bring it into a contemporary moment. Through these pure interrogations, Awartani invigorates the traditional, mapping and deconstructing value to demonstrate the potential and enduring relevance of a highly powerful visual language capable of concurrently articulating deep truths of mathematics, science, history, and spirituality. As such, her work becomes a vigorous rebuttal that counters the uninformed perspectives that dismiss these practices merely as a decorative art

or ‘craft’.

China’s Yinchuan City host the first biennale in September 2016 with Anish Kapoor, Ai Weiwei, Abigail Reynolds, Alke Reeh, Andrew Miller, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, and more

Madam Liu, Director of Museum of Contemporary Art Yinchuan (MOCA Yinchuan), announced today that the museum will hold its first biennale. To be curated by internationally acclaimed artist, curator and co-founder of Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Bose Krishnamachari, the exhibition will be held from September 9 to December 18, 2016 on the premises of MOCA Yinchuan and will include an engaging display of artworks both inside and outside the museum.

Titled For an Image, Faster Than Light the inaugural edition will witness more than 80 international artists representing all facets of the global spectrum and from all parts (east–west, north–south) working on contemporary issues that the world has to contend with.

According to the concept note presented by Curator Bose Krishnamachari, “This biennale in China can thus postulate different themes, including spiritual and social consciousness, an examination of political narratives and critical global engagement and an acknowledgment of a collective responsibility therein.”

“A light to be seen through art’s eyes. It is indeed a circle in which we seek, from beginning to end, a light to hold within the image of a finger bowl,” he says. The inaugural Yinchuan Biennale thus proposes to create a discourse on all the conflicts that the world is currently confronted with and perhaps makes possible propositions through a global creative confluence.

Many of the works will involve artistic residencies in MOCA Yinchuan’s International Artist Village and research travels to Yinchuan to create site-specific works. “To this international biennale,” feels MOCA Yinchuan’s Artistic Director Suchen Hsieh,” we are going to set up the first professional culture promotion base among the cites on China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ Strategy list.”

The Museum of Contemporary Art Yinchuan is the first contemporary museum along the Yellow River in the northwest of China. In 2015 it found place among the best new museums. The biennale will also see a host of cultural activities like music programmes and seminars on the various aspects of the concept note. Some of the participating artists will be conducting workshops for children. Madam Liu says, “the first Yinchuan Biennale will be an excellent platform to showcase the best of contemporary global art.”

![<p><span class="viewer-caption-artist">Dana Awartani</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-title"><i>All [heavenly bodies] swim along, each in its orbit</i></span>, <span class="viewer-caption-year">2016</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-media">Mixed Media</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-dimensions">150 x 150 cm</span></p>

<p><span class="viewer-caption-aux"></span></p>](/images/29138_h960w1600gt.5.jpg)